What is Britain’s place in the world? The British ruling class has been asking itself this question for the best part of a hundred years, as it has struggled to come to terms with its ever-deepening decline, decade after decade.

The latest event to expose its diminished status and prompt a bout of soul searching is the collapse of the China spy trial, an episode reminiscent of the recent Netflix spy drama Black Doves.

Two British citizens, Chris Cash and Chris Berry, were accused of spying on Britain for China over a sustained period of time.

But last week, the case against them collapsed, for what are on the surface technicalities: the law was changed after they had been charged, which now required the government to state that the country in question (China), was a threat to national security at the specific time those charged were spying on its behalf.

According to the Crown Prosecution Service, it proved impossible to get the government to state this. Instead, it said that “the UK Government is committed to pursuing a positive relationship with China.”

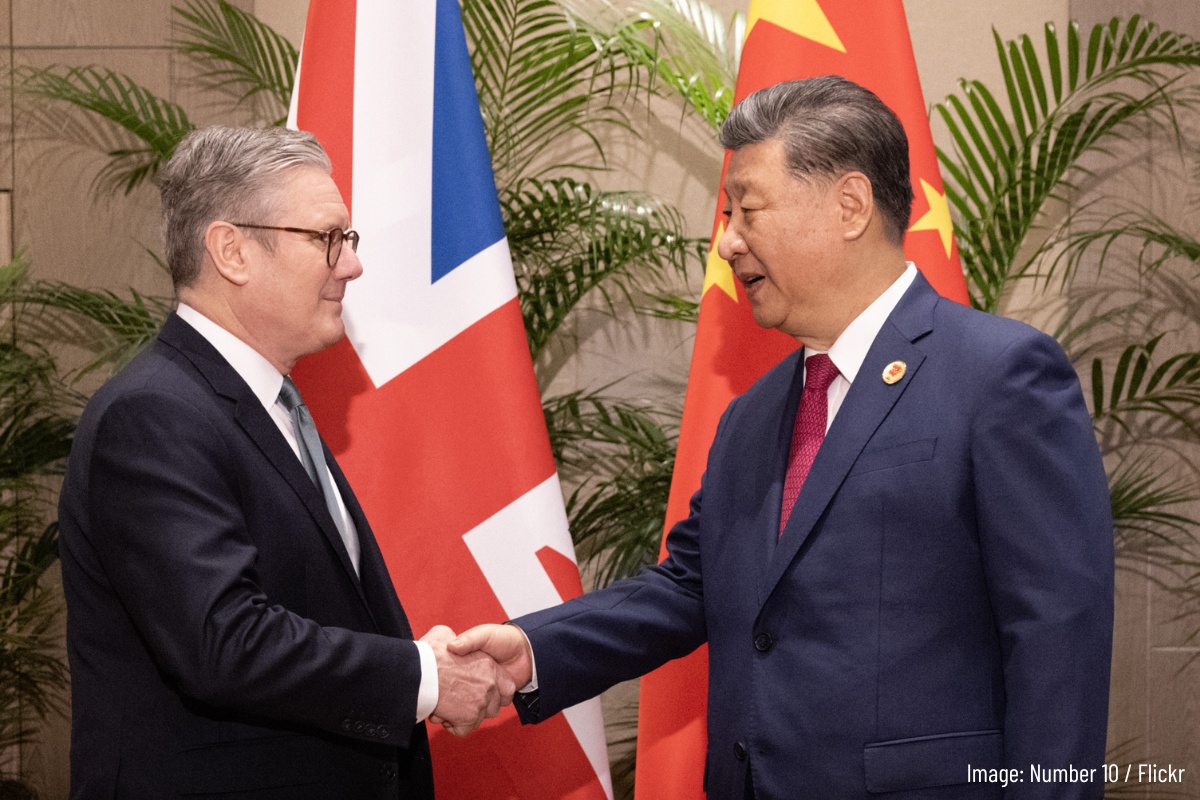

It is therefore clear that the trial collapsed because Starmer has changed the government’s attitude to China, from it being a “threat”, as Liz Truss defined it, to a country with which to seek a “positive relationship”.

‘Developing country mindset’

The Economist quotes an expert on Anglo-Chinese relations that this new policy reflects a “developing-country mindset” in the British state. What do they mean by this?

The Labour government’s unwillingness to give a candid assessment of Chinese activity might have doomed the prosecution of a recent spy trial. The Tories can smell blood https://t.co/OMAhB2eeMY

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) October 17, 2025

We are told it is a mindset “in which trade, investment, and growth are prioritised over national-security concerns”, which is deeply ironic, because British capitalism has consistently achieved lamentably low levels of investment and growth.

What this really means is that British capitalism is chronically weak, and Britain has in reality shrunk to being a third rate power, and so has no choice but to go begging to the Chinese for investment and technology.

In 1990 China Was The World’s 11th Largest Economy & The UK Was The 5th. What Happened Next?

More Countries & all data here: https://t.co/5FlVqf19Pf pic.twitter.com/EYWRYPTabY

— Brilliant Maps (@BrilliantMaps) October 19, 2025

Starmer is seeking to gain a comparative advantage over rivals such as Germany by being more open to Chinese business and, as the collapse of this trial shows, being more acquiescent to its spies.

Speaking of acquiescing to espionage, Starmer’s government has also intervened to prevent the blocking of construction on China’s new embassy in London. Starmer himself is on video telling Xi Jinping that “you raised the Chinese embassy building in London when we spoke on the telephone. We have since taken action by calling in that application”.

It has always been the case that embassies serve as bases for espionage, and governments have tolerated a certain level of that in the expectation that the favour be returned for their respective embassy, as well as facilitating other favours and deals.

The proposed new Chinese embassy would be the largest in London (surely a devastating blow to the egos of Trump, and American diplomacy in general, after the construction of their own super embassy in 2017). It would sit above key internet cables serving the City of London, and the purpose for certain rooms has been redacted in the plans.

It is safe to say that the embassy would indeed facilitate and enhance Chinese spying on the British state, and its capacity to intervene. Yet for Starmer’s government, this is a price worth paying for gaining lucrative trading terms, investment and technology from China.

Contradictions and splits in the ruling class

Unsurprisingly, the Tories have leapt on this in an attempt to score points over the government.

In response, Starmer is blaming the Tories for having made the legal changes that led to the collapse of the trial (despite the fact it was his government that chose not to describe China as a threat to national security, causing its collapse).

The Tories are also blaming the national security adviser Matthew Collins, who is in turn blaming the Director of Public Prosecutions for dropping the case. In other words, the British establishment is openly split.

This open split is one of many in recent years. What does it reflect? Britain does not simply have a “developing-country mindset” – it has a “developing-country reality”, or rather a “declining-country reality”.

Developing countries are unable to play an independent or leading role in the world market, and so are forced to seek investment and ‘security guarantees’ from imperialist powers.

Sometimes, they try to balance between competing powers, playing them off against one another for domination over the developing country in question, but this game can threaten to split its ruling class and destabilise the country.

In attempting to curry favour with China, Starmer is reversing the Tories’ heavily pro-America stance.

It makes sense for the British capitalist class, who are desperate for investment, to be friendly with China, except that Britain has for decades based itself on being America’s best friend and most loyal servant. A more friendly orientation to China, in these times of fierce imperialist rivalry between the US and China, is bound to create splits.

The difference a declining country like Britain has with a developing country, is that the ruling class of the former cannot accept the reality of decline. That is certainly the case for the British ruling class, encumbered as it is with delusions of grandeur inherited from its imperial past.

Far from having a “developing-country mindset”, then, it has an “imperialist-power delusion”.

For the Tories, Starmer’s bending the knee to China in the hope of investment from it is unacceptable, because it is an admission of Britain’s decline and its inability to counter Chinese power.

Britain will end up with the worst of both worlds. Unable to accept its real status, it resists China’s advances – irritating it without being able to achieve anything. In turn, it fails to impress the US, and earns only its suspicion.

Unable to chart a rational course, unable to stay united, the British establishment continues to blunder around, accelerating its decline.