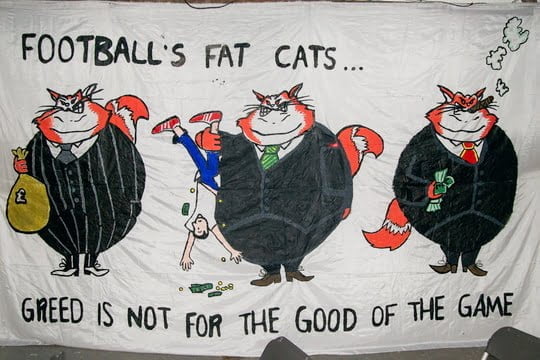

Capitalism’s rampant inequality pervades the whole of society – including the world of football. Whilst rich clubs like Man City rake in millions, outside of the Premier League, many clubs face the threat of bankruptcy.

The idea of a financial crisis in football may seem laughable, given that the sport’s headlines are often dominated by the latest multi-million pound transfer or scandal involving an extremely well-paid player. But there has been a ‘quiet’ crisis ongoing in the English lower leagues, with many clubs in a precarious position. Some are even being pushed to the brink of extinction.

Although there had been some signs before this, many argue that the real beginning of the commercialisation of football was with the foundation of the Premier League in 1992. At this time, the 22 top clubs in English football split away from the Football League to enable them to negotiate much larger TV deals.

Few would have expected (despite it being the logical conclusion) that the entire existence of English lower league football would later come under threat as a result.

Profits at the top, bankruptcy at the bottom

In the 27 years since the founding of the Premier League, the value of TV rights has exploded. Contracts between sports channels and clubs are now worth almost £3 billion per year, with the bottom placed Premier League club receiving in excess of £100 million as their share.

This has meant that most Premier League clubs are now very profitable for their owners. The figures for the 2017/18 season show that the country’s top 20 clubs made a combined total of over £300 million profit.

The contrast with the rest of professional football in England could not be greater. The English Football League (EFL) covers the next three tiers – the majority of professional football in England outside of the Premier League.

For a club in the second tier (the Championship), each club receives around £7 million in payments from TV contracts and distributions from the Premier League. For clubs in the third and fourth tiers (League One and League Two) the figures are around £1.3 million and £900,000 respectively.

With clubs simply seen as money making machines by their owners, the result is that many spend vast sums of money “chasing the dream” in an attempt to win promotion to the Premier League, with its almost guaranteed profits.

Across the EFL as a whole, 52 of the 72 clubs made a loss, with a combined total loss of almost £400 million. In effect, all barring 20 of the EFL clubs would be bankrupt tomorrow if their owner gave up on “chasing the dream” and stopped funding them.

This figure may even be an underestimation, as many clubs perform ‘accounting tricks’ in order to comply with the very limited financial regulations that the EFL enforce. This has begun to cause concerns for many insiders in the football world, with one quoted as saying: “It is not outlandish to worry that 75 percent of clubs in the bottom two divisions have zero long-term future in their current form.”

Broke Bolton

While these figures demonstrate that many clubs are in a precarious position, the situation is much more dire for some. Bolton Wanderers are one club in a particular crisis, with the players going on strike twice in the last year in retaliation for not being paid wages.

Bolton’s players refused to train earlier in the year, as both themselves and the ‘ordinary’ staff had not been paid their wages almost a month after being due. They then refused to play a game later in the season for the same reason (although the game would have probably been called off in any event, as matchday staff were considering refusing to work for fear of not being paid).

While many of the more senior players were able to avoid major difficulties by being paid late, the situation was much worse for many of the younger players and the club’s administrative staff. It was reported that some of the senior players were having to lend money to the younger players so that they could afford to pay their rent and travel to training. For the non-playing staff, many were facing destitution without their wages.

This led to magnificent acts of solidarity where supporter groups (including those of rival clubs) organised food banks to ensure that the staff would be able to survive until their wages were paid.

The story of Bolton is even more shocking when you consider the role that the club’s owner, Ken Anderson, played. Anderson was previously banned from being a company director for eight years for diverting money to his own bank account, rather than paying a VAT bill. Despite his club’s staff being forced to use food banks, Anderson has still been taking almost £700,000 out of the club each year in consultancy fees alone.

The Bolton owner was also quoted as telling one of his peers, Dale Vince at Forest Green Rovers, that he should sue Bolton over an unpaid transfer fee for a player. Since all of Anderson’s loans were secured, he could liquidate the club and Vince would only get 10% of the transfer fee owed! Such disgraceful behaviour has led to Anderson being widely criticised across football.

Bolton are far from the only club who have faced crisis. In the last few months alone, Morecambe, Bury and Southend United have all paid their players and staff late. Many other clubs have reported financial difficulties. Some have reported record losses.

It is also widely expected that there will be more clubs in trouble over the summer, as there are no competitive games being played, and therefore no gate money being collected.

It is clear that this is far from a case of a few bad apples – it is the entire concept of private ownership in football that encourages owners to gamble the future of clubs in order to rise higher in the leagues and make greater profits.

In it for the profits

Aside from financial difficulties, a much darker side has emerged. Some extremely shady individuals are getting involved in football club ownership in order to make a quick profit.

The story of Coventry City has shocked many football fans. The club was forced to play its ‘home’ games outside of Coventry for the second time in the last few years. For next season, at least, Coventry will be playing at Birmingham City’s stadium, St. Andrews. This follows threats of expulsion from the EFL if they didn’t organise a suitable stadium.

A similar situation developed several years ago, where Coventry’s owners (the hedge fund SISU) temporarily moved the club’s games to Northampton due to a dispute over the rent of the Ricoh Arena in Coventry. This dispute was widely regarded as being the fault of SISU for refusing to pay the rent whilst bargaining to try and reduce it.

While the latest dispute is a complex three-way argument between the football club, Coventry City Council, and the rugby club Wasps (now the stadium’s owners), it would be difficult to believe that SISU are completely blameless following their previous record.

Few would also forget the role of the Oyston family in the sorry saga that was Blackpool. Among the many misdemeanours committed by father and son, Owen and Karl, scandalous incidents include: being found by the High Court to have “illegally stripped” almost £27 million from the club; suing the club’s fans for referring to them as “asset strippers”; provocatively taking pictures in front of banners protesting their ownership; and mocking a disabled fan by text message (including referring to the fan as a “massive retard” and an “intellectual cripple”).

Although the Oystons were finally forced out of Blackpool earlier this year, their very presence in football is a chilling sign of the types who are attracted to the possibility of quick profits from football.

Reclaim the game

Many people refer to football as “the beautiful game”. But it is a beautiful game that is on the brink of being destroyed. While many would argue (correctly) that the behaviour of the Andersons and the SISUs of this world is abhorrent, they are simply the worst and most obvious culprits of a system that allows football clubs to become profit-making businesses for the benefit of the bosses.

Private owners of football clubs will always be tempted to make decisions based purely on (short and long term) financial gain, regardless of any regulations that try to prevent this.

Many fans often talk of “reclaiming the game”. But the only way that we can truly reclaim the game is for the dubious individuals and profiteers to be kicked out of football. This means putting all clubs under the ownership and control of their supporters and of wider society. Only in this way can we save the game from its pending crisis.

Meanwhile at Man City…

By Stan Laight, Sheffield Hallam CLP

This year’s Premier League season featured some of the best football that fans have seen for years. Manchester City FC completed the domestic treble by narrowly winning the league and retaining their title as champions, coming one point ahead of Liverpool FC.

This is in stark contrast to the fortunes of Bolton Wanderers FC who entered administration, were relegated to League One, and opened up a food bank for players and staff who had not been paid for almost three months.

These two clubs are examples of the growing inequalities between the top and lower league clubs fighting for their survival.

Man City is owned and funded by Sheikh Mansoor, an Emirati royal and the Deputy Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates, whose wealth stands at around a staggering $5bn. He also has stakes in five other clubs around the world including New York City FC, which has been the subject of much investigation over its close ties with Man City. Sheikh Mansoor’s vast personal wealth and links to the oil industry have allowed him to pump unrivalled amounts of money into the club.

Although Man City have won a domestic treble, they are being investigated by UEFA for breaking FIFA Financial Fair Play regulations (FFP). This is in addition to investigations by the Premier League, English FA and FIFA regarding signing youth players.

If found guilty, the club face a fine, a transfer ban, and possibly a season-long ban from European football. They are desperate to win a trophy in Europe, as this offers up to over €100 million in prize money for going all the way to the final.

However, these punishments will be seen as just a hiccup for the club. Remember, Man City ‘earned’ nearly £151 million just from the Premier League in prize and TV deal money.

When the club was penalised in 2014 for breaching FFP rules they were fined £49m and were forced to restrict their European squad and limit incoming transfers. However, they actually received £33m of their fine back through UEFA prize money. This has also been the case with other successful and wealthy European clubs such as Paris St. Germain, AC Milan and Real Madrid – given a slap on the wrist and a refund for the trouble.

Man City are able to get away with breaking FFP rules because they generate huge profits for many football institutions, broadcasters and shareholders. On the other hand, Bolton Wanderers are punished for poor performances, and without billionaire investors they are unable to generate such profits.

But the purchases of clubs by billionaire investors is often met with strong resistance from fans – for example, Malcolm Glazier at Manchester United, Mike Ashley at Newcastle United, Owen Oyston at Blackpool FC.

Some fans respond by setting up new clubs. But these are unable to challenge the overwhelming power that well-established clubs and football institutions have accumulated. And they face their own challenges to reconcile interests between owners and supporters.

The Premier League has become a place for billionaires to spend their money on dismantling working-class institutions into profitable investments. Our task must be to kick the capitalist class out of football.

But this cannot be done one club at a time. It requires a fundamental transformation that sees all clubs and stadiums owned and managed by supporters, workers, and players. Our leisure time must be free from the tyranny of the ruling class. Show capitalism the red card and fight for socialism!