The history of capitalism is littered with bubbles: periods in which over-excited investors pour their money into ultimately worthless ventures – from the Dutch tulip mania of the 1630s, to the South Sea and Mississippi frenzies of 1720, to today’s cryptocurrency craze.

The above examples are all cases of outright speculation – that is, attempts to make money out of money, without any investment in actual production.

There was never any underlying value or profit being generated in these instances. Instead, spurred by hype and hysteria, those snapping up tulip bulbs – as with those holding Bitcoin today – were making a one-way bet that prices would continue to rise; that they could personally gain by buying cheap and selling dear.

Real value can only come from applying socially necessary labour in the process of production. Speculation, by contrast, merely redistributes value already created elsewhere in the economy. Any profits made from such pursuits are therefore completely parasitic.

Generally speaking, when these bubbles eventually burst, the fallout is limited. Those who exit early make a tidy sum. On the other side, some unfortunate, naive souls swept up in the delirium may lose their savings. But the wider damage to the economy is normally constrained.

There are other cases, however, where manias occur in response to genuine economic developments, as investors pile into new markets – driven both by the hope of making super-profits and by ‘FOMO’, the fear of missing out.

In particular, looking back over the last two centuries, we can see that every major technological breakthrough has been accompanied by bouts of feverish activity and herd-like investment.

From the railways to the internet: transformative technologies have always given rise to metaphorical ‘gold rushes’, as a host of business-owners and entrepreneurs – in many cases, mere fraudsters and con-artists – flock into a promising nascent industry, spying an opportunity to get rich quick.

Unlike the aforementioned instances of pure speculation, these bubbles can be far more economically destructive; more contagious and longlasting.

In the short term, while the euphoria still lasts, they suck in resources that could otherwise be deployed more effectively elsewhere. The result is enormous distortions and waste within the economy.

In the long term, when boom turns to bust, they can trigger a panic, leading to a cascade of bankruptcies and credit crises – and, in turn, to a painful slump in production.

Today, as we have reported on recently elsewhere, there are widespread warnings about a gigantic bubble developing in the modern technology sector, centred around ‘generative’ artificial intelligence (AI): tools, models, and virtual assistants, like ChatGPT and Gemini, based on ‘deep learning’ and large amounts of data, processing power, and energy.

What are the perspectives for this AI gold rush? What would be the consequences of this latest tech bubble bursting? And what does all this market madness tell us about capitalism and its contradictions?

Stock speculation

In reality, the current AI frenzy is not one bubble, but a foam of interconnected bubbles, like a frothy capitalist cappuccino.

There is a purely speculative element to this phenomenon, in the form of the rising – but volatile – share prices of the Big Tech firms.

Growth in the US stock market is being driven almost entirely by increased demand for shares of the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’: Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, Nvidia, and Tesla.

According to the latest estimates, these major monopolies account for over one-third of the value of the S&P 500 between them – treble their total slice a decade ago. Economists at Deutsche Bank suggest that they have contributed around half of the gains in the stock market over the past year. Others put the figure even higher.

And everyone from institutional investors (e.g. asset management companies, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds) to retail traders (i.e. Joe Public) are continuing to plough money into these companies, helping to push their stock prices up and up.

As a result, Nvidia is now the world’s most valuable business, recently becoming the first ever $5 trillion company. Coming in behind are household names such as Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet (the parent company of Google), at $4.0 trillion, $3.7 trillion, and $3.5 trillion, respectively.

In this respect, the AI bubble can seem little different to the 17th century tulip-bulb mania or the contemporary hype around crypto, only with tech shares acting as the latest vehicle for speculation.

But there is another – possibly even more pernicious – layer to this process: the eye-watering sums being invested in AI-related infrastructure.

This makes today’s AI fever more akin to other historic technology-focussed frenzies, than to any merely speculative episode from the past; and, in turn, potentially far more explosive when the bubble eventually bursts.

Betting big

The logic of capitalist competition is forcing all the Big Tech companies to throw ever-greater resources into constructing the hardware and software needed to advance AI.

They are all engaged in a ruthless arms race; embarking on a crusade for the holy grail: to create so-called artificial ‘superintelligence’ – that is, models capable of making a quantum leap when it comes to automating a wide range of tasks and processes.

The first to develop such ‘artificial general intelligence’ (AGI), it is hoped, would find themselves in a ‘winner takes all’ position. As with other monopolised markets, the leader in this field could quickly dominate the industry and make mega-profits.

The major imperialist powers, meanwhile, see a strategic interest in pursuing AGI. Such technology, if realised, could confer important military and intelligence advantages, altering the balance of forces on the battlefield and in the skies for its possessor.

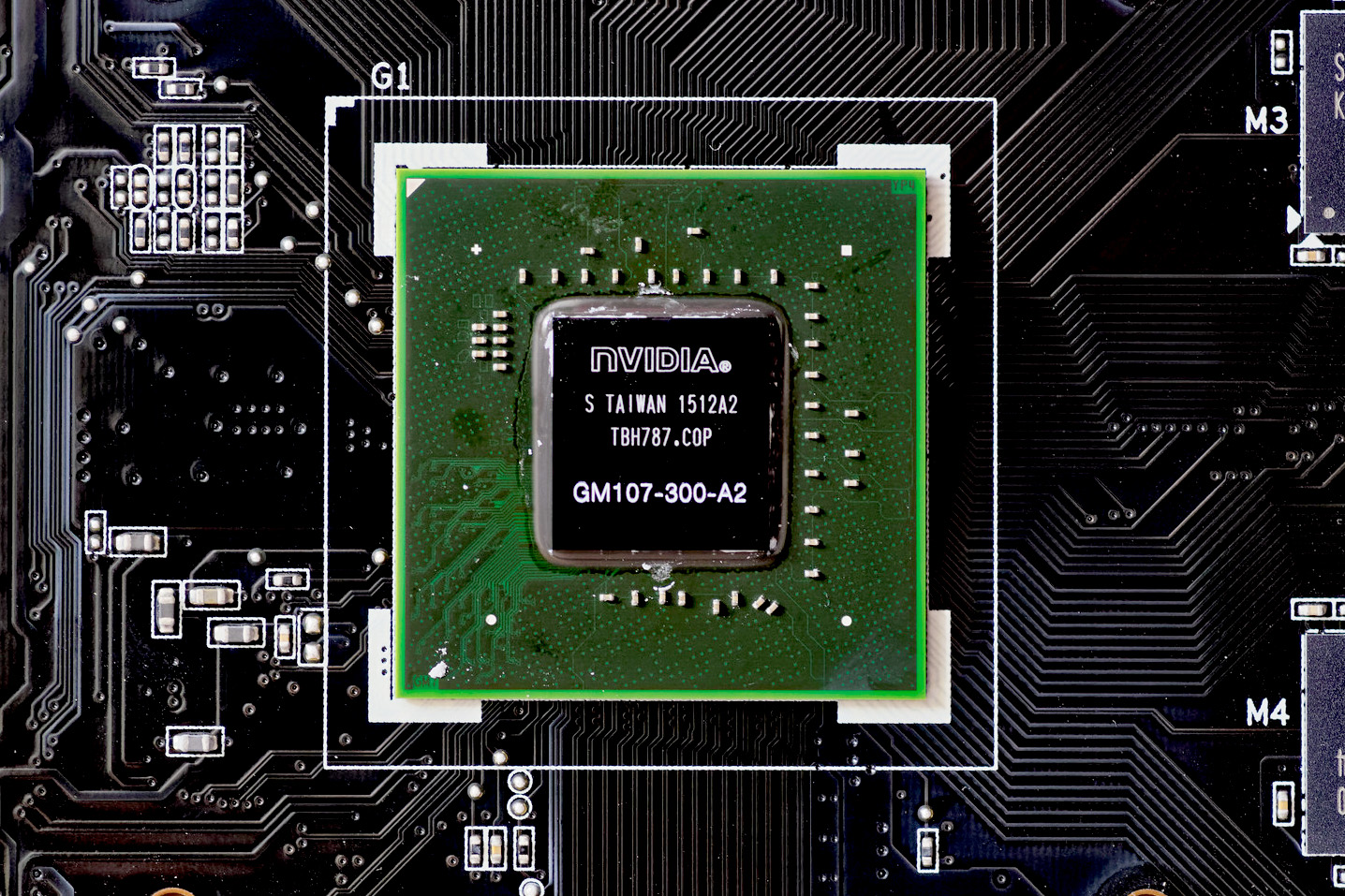

On the ground, this means constructing ginormous data centres, stuffed full of state-of-the-art silicon chips (like those produced by Nvidia), to train the algorithms behind bots like ChatGPT and Gemini, owned by OpenAI and Alphabet, respectively.

Similarly, ‘hyperscaler’ firms like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are building mammoth data centres to host (highly-profitable) cloud-based services, including the provision of computing power, storage, and analysis for other businesses.

Backed by their respective governments, therefore, all the key tech corporations are plunging billions – or even trillions – into developing bigger and better AI models.

In September, for example, while showing off the company’s flagship data centre in Texas, OpenAI boss Sam Altman announced that five more huge complexes will be built across the USA as part of the $500 billion Stargate AI-investment project, which has been promoted by President Donald Trump.

And this is only the start. According to the latest estimates, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta alone will collectively spend a whopping $750 billion on AI infrastructure over the next couple of years.

Projections from Morgan Stanley give a sense of the hype within and around the tech sector, suggesting that AI-related investment could rise to a cumulative total of $2.9 trillion across the industry by the end of 2028. Consultants at McKinsey put the figure at $6.7 trillion by 2030.

To put this into perspective, the size of the American economy currently stands at around $30 trillion. In other words, the strategists of capital are predicting that the money poured into AI over the next few years could amount to almost 10 percent of US GDP.

In reality, such forecasts are unlikely to materialise. With questions increasingly being raised about the viability of the AI industry, and its capacity to generate profits, much of this investment will probably never see the light of day.

Nevertheless, such numbers demonstrate the speculative madness that is gripping the markets.

In any case, the sums already being thrown around are huge bets to be making by any standards. The (potentially $7 trillion) question is: will they pay off? And who will foot the bill if they don’t?

Hype turns to doubt

Not so long ago, tech bosses were declaring that a new dawn was on the horizon, thanks to rapid developments in AI and the possibility of imminent superintelligence.

Even serious bourgeois mouthpieces echoed these sentiments. In July, for example, The Economist published a lead article discussing the potential for annual economic growth of 20 percent or more, thanks to AI-powered leaps in productivity.

The stock market seemed to agree with these forecasts, meanwhile, reflected in a seemingly inexorable rise in the valuations of the leading tech monopolies.

All of this seemed to justify, at least in part, the huge infrastructure investments being made by the world’s leading AI firms.

Now, however, doubts are beginning to intrude on the hype.

A recent MIT survey, for example, found that 95 percent of AI-driven projects fail to make it beyond the pilot stage. This means that the technology could not deliver significant revenue growth for those organisations deploying it.

This news immediately provoked alarm on the markets, with tech firms like Nvidia seeing a drop of 3.5 percent in their share price. And it prompted Sam Altman and Mark Zuckerberg, CEOs of OpenAI and Meta, respectively, to admit that a bubble may be forming around AI.

“There is definitely a possibility, based on past large infrastructure buildouts and how they led to bubbles, that something like that could happen here,” commented Zuckerberg, referring to previous tech-centred manias.

“Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? My opinion is yes,” stated Altman, meanwhile. “I do think some investors are likely to lose a lot of money, and I don’t want to minimise that – that sucks.”

Further warning signs came earlier this month, meanwhile, as global stock markets fell suddenly in response to fears about a growing AI bubble, with leading bankers predicting a “serious market correction” for “lofty tech valuations”.

Within weeks of their aforementioned article about the glowing prospects for AI, therefore, The Economist had done a 180-degree U-turn, penning a featured piece entitled “What if the $3trn AI investment boom goes wrong?”

“Even if the technology succeeds, plenty of people will lose their shirts,” the liberal outlet warns. “And if it doesn’t, the economic and financial pain will be swift and severe.”

In short, the booming tech sector may be on the verge of a mighty bust – one that has the potential to cause chaos and catastrophe across the global economy.

“Vibes not returns”

The authors of the above article point to a number of dangers.

For starters, there is the potential lack of profitability from this supposedly transformative technology, as highlighted by the MIT report.

In turn, it is likely that AI boosters are vastly overestimating the market for their goods and services.

This is not the place to comment on the abilities and powers of AI – or lack thereof. But regardless of whether AI-fuelled productivity increases are realised or not, it is clear that even the most promising of predictions do not justify the sums being spent by the Big Tech firms, or the inflated prices of their shares.

For the S&P 500 as a whole, the price-to-earnings ratio currently sits at 40 – just shy of the record level seen at the time of the 2000s dot-com bubble. For one third of the firms in this tech-dominated index, the figure is over 50.

In other words, corporate valuations on the stock market massively exceed the actual income or revenue that these businesses bring in.

The stock market has become completely divorced from the real economy by other measures also. “Since 1970, the total value of all publicly traded US stocks has averaged about 85 per cent of US GDP,” the Financial Times reports. “On Tuesday [28 October], the metric rose to a record 225 per cent.”

There are also major private companies in the industry: those who do not issue publicly-traded shares. OpenAI is one of these, relying on venture capital and other sources of investment.

There is seemingly no shortage of punters willing to put billions-upon-billions of their money into Altman’s business, helping fund an estimated $1.4 trillion in AI infrastructure investment over the next eight years. Yet the ChatGPT developer is on course to take in just $13 billion in revenue (not profit) from paying customers in 2025.

Similarly, Ed Zitron, a prominent tech commentator and AI sceptic, estimates that the Magnificent Seven will have invested $560 billion in AI infrastructure over the two years of 2024-25. But their collective revenue from generative AI services in this period will come to only $35 billion. And their overall profit from this technology will be zero.

When it comes to the AI world, however, as Zitron summarises: “this is a bubble driven by vibes not returns.”

Depreciation and drain

Much of the investment in AI-related infrastructure, meanwhile, could well prove to be redundant and worthless.

For starters, there are widespread concerns that the current strategy of the tech monopolies – to hope that bigger equates to better when it comes to AI models – may be reaching its limits.

Already, there is talk that AI developers may be running out of data upon which to train their models. This was reflected in the shrug that greeted the launch of OpenAI’s latest iteration of ChatGPT, which offered only quantitative – not qualitative – improvements.

Many businesses, meanwhile, have expressed a preference for smaller, bespoke tools over the generalised ‘large language models’ (LLMs) that form the focus of firms like Alphabet, Meta, and OpenAI.

Furthermore, the pace of change within the industry is such that the technology at the heart of this AI infrastructure can quickly become obsolete.

In 2023, for example, Meta ripped down one of its data centres in Texas whilst it was still under construction, in order to replace it with a new version based on more advanced microchips.

In his economic writings, Karl Marx outlined how real value is created through the application of socially necessary labour time in the process of production.

Fixed (constant) capital like machinery, factories, and infrastructure, he explained, does not create new value. Rather, equipment and plant transfer their value – the ‘dead’ labour crystallised within them – into the end commodity over the course of their lifespan.

If a capitalist spends $1,000 on a machine, for example, then this investment is divided up into the mass of commodities that it helps to produce during the period it remains in use.

Such a machine might produce one thousand items in a ten-year lifespan. It would therefore pass on $1 of value to each individual commodity. After this, the machine will become worn out and will need to be replaced.

If this lifespan is cut short, however, due to obsolescence, then this fixed capital will struggle to reproduce its own value, in the form of sellable commodities.

Or put another way, the labour time embodied in this machinery and infrastructure will have proven itself to have been socially unnecessary – thus writing off its nominal accounting value.

Marx referred to this as the moral depreciation of constant capital, in contrast to the physical depreciation represented by wear and tear.

“In addition to the material wear and tear,” Marx writes in Capital, “a machine also undergoes, what we may call a moral depreciation. It loses exchange-value, either by machines of the same sort being produced cheaper than it, or by better machines entering into competition with it.”

“In both cases, be the machine ever so young and full of life, its value is no longer determined by the labour actually materialised in it, but by the labour-time requisite to reproduce either it or the better machine. It has, therefore, lost value more or less…

“When machinery is first introduced into an industry, new methods of reproducing it more cheaply follow blow upon blow, and so do improvements that not only affect individual parts and details of the machine, but its entire build.”

“This process,” he continues in the third volume of his magnum opus, “has a particularly dire effect during the first period of newly introduced machinery, before it attains a certain stage of maturity, when it continually becomes antiquated before it has time to reproduce its own value.”

What does this mean for the current AI investment boom?

“An unusually large share of capital investment is being devoted to assets that depreciate quickly,” The Economist informs us. “Nvidia’s cutting-edge chips will inevitably look clunky in a few years’ time. We estimate that the average American tech firm’s assets have a shelf-life of just nine years, compared with 15 for telecoms assets in the 1990s.”

Elsewhere, however, the same magazine reports that Big Tech firms are consistently exaggerating the lifespans of their infrastructure investments:

“In July Jim Chanos, a veteran short-seller, posted that if the true economic lifespan of Meta’s AI chips is two to three years, then “most of its ‘profits’ are materially overstated.” A recent analysis of Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta by Barclays, a bank, estimated that higher depreciation costs would shave 5-10% from their earnings per share.”

“Apply this logic to the entire AI big five and the potential overall hit to the bottom line is huge,” the authors conclude. Estimates of the collective devaluation for these tech monopolies could come in at anywhere from $1.6 trillion to $4 trillion – “equivalent to one-third of their collective worth”.

And if hyped-up expectations around AI fail to materialise, with super-profits unforthcoming, then even more value could go up in smoke.

Like the trillions spent on arms every year, therefore, much of this AI infrastructure could end up being the economic equivalent of an expensive scrapyard: wasteful, unproductive investment that acts as a drain on the wider economy.

Dangerous debt

If that were the end of the story, then the bursting of the AI bubble might not seem that threatening. After all, there would be little love lost for billionaire bosses like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg if their fortunes evaporated overnight.

Unfortunately, however, as with the California gold rush of the mid-1800s, today’s frenzy – centred around Silicon Valley – has pulled in all manner of swindlers and snakeoil salesmen, hoping to make a quick buck.

Alongside the Big Tech companies on the West Coast, the big banks and financial firms on the East Coast are also betting big on AI.

Giant asset managers like Apollo and Blackstone are getting in on the game: lending to the tech monopolies; buying up stakes in data centres; and investing in other businesses that form part of the supply chain for these sites.

According to Morgan Stanley’s estimates, the Magnificent Seven will likely stump up the lion’s share of the almost $3 trillion in capital expenditure [capex] on AI infrastructure expected between now and the end of 2028, paid out of their sizable accumulated cash piles.

But the rest – the $1.5 trillion financing gap – is predicted to come from private markets. This includes an increasing amount in credit / debt. Tech firms like Meta and Oracle, for example, recently sold $30 billion and $18 billion worth of corporate bonds, respectively, to raise money for their AI expenditure.

The murky ‘shadow’ banking system is a part of this, helping to channel investors’ funds into AI projects, beyond the oversight of regulators and watchdogs.

According to figures from UBS, around $450 billion in private credit loans could be threatened by a crash in the tech sector. But even that may only be the tip of a very large iceberg.

Like with the subprime mortgages that blew up the global financial system in 2007/08, data-centre debt is being packaged up and sold on in all manner of crafty and confusing ways.

In short, we could be witnessing the development of the latest financial weapons of mass destruction.

Similarly, so-called ‘margin’ debt is also surging: that is, leveraged purchases of (primarily tech) shares; money borrowed by investors to buy stock.

Historically, an increase in such loans has been a tell-tale sign of speculation; a clear indicator that a bubble is forming. And now this margin debt stands at over $1.1 trillion, up by 39 percent since April.

Big Tech firms, meanwhile, are propping each other up, creating a veritable house of cards.

Recently, for example, Nvidia announced that it is planning to invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI, so that the latter can buy up microchips from the former. And there are a whole host of other circular deals and incestuous financial relationships within the industry, between OpenAI and major tech firms such as Microsoft, Oracle, CoreWeave, AMD, and Broadcom.

In other words, a crisis or collapse in investor confidence for any of the big players within the tech industry would quickly cascade throughout the sector – and beyond.

“I think no company [in the tech sector] is going to be immune,” stated Alphabet boss Sundar Pichai recently, commenting on the potential impact of the AI bubble bursting.

The result of all of this is that nobody really knows how far the web of risk and loans extends – or who will be on the line if (or when) any debts turn sour.

“Three data centres in a trench coat”

The reach of this bubble extends beyond just the technology and financial sectors, however. In truth, the AI investment boom is pulling the whole of the US – and world – economy into its orbit.

To get a sense of scale: by some estimates, if you add together all the money going into AI buildout, this is contributing more to measured US economic growth than total consumer spending; by other estimates, the AI boom accounts for 40 percent of the increase in America’s GDP.

So far this year, AI capex, which we define as information processing equipment plus software has added more to GDP growth than consumers’ spending. pic.twitter.com/D70FX2lXAW

— RenMac: Renaissance Macro Research (@RenMacLLC) July 30, 2025

Others have calculated that the investment in data centres, microchips, and associated energy supplies in recent years, adjusted for inflation, comes to more than it cost to build the entire US highway system over four decades.

At the same time, some economists have suggested that AI capex is the only thing stopping the American economy from going into recession.

⚠️Without the tech spending the US economy would be in a RECESSION:

US Real GDP Growth year-over-year would be negative or close to zero when excluding tech spending.

And this is still before major revisions accounting for the WAY weaker job market than initially reported… pic.twitter.com/bB4itCdCjp

— Global Markets Investor (@GlobalMktObserv) September 24, 2025

“AI machines – in quite a literal sense – appear to be saving the US economy right now,” writes George Saravelos in a recent Deutsche Bank research note. “In the absence of tech-related spending, the US would be close to, or in, recession this year.”

“Look beyond AI and much of the economy appears sluggish,” comments The Economist. “Real consumption has flatlined since December. Jobs growth is weak. Housebuilding has slumped, as has business investment in non-AI parts of the economy.”

According to one investor, AI investment is effectively “a massive private sector stimulus programme”. Or, as another American economic commentator aptly put it: “Our economy might just be three AI data centres in a trench coat.”

If Big Tech’s pie-in-the-sky profit projections do not come to fruition, in other words, AI-related investment will dry up, causing the US economy to fall into a slump. And this is before accounting for any financial contagion, as outlined above; or for the impact of a stock market crash on wider economic demand (more on this below).

As the Cassandra-like Saravelos concludes:

“It may not be an exaggeration to write that Nvidia – the key supplier of capital goods for the AI investment cycle – is currently carrying the weight of US economic growth. The bad news is that in order for the tech cycle to continue contributing to GDP growth, capital investment needs to remain parabolic. This is highly unlikely.”

Anarchy of the market

On the one hand, then, the US economy is seemingly being held afloat by the AI boom. On the other hand, this same force is also squeezing non-tech sectors of the economy.

Whether it be capital, labour, land, energy, water, or raw materials: AI investment is sucking up resources that could be deployed in other – more productive – industries.

Competition for these resources exacerbates supply-side strains, adding to the inflationary pressures in the economy. This comes at a time when Trump’s tariffs and curbs on migrant labour are already pushing up prices. This, in turn, means that interest rates and borrowing costs remain elevated for households and businesses, weighing on overall demand.

The price of energy and water, in particular, is being pushed up by data centres’ seemingly insatiable appetite for these inputs, which are needed to power and cool the massive racks of processing units that sit inside these buildings.

So far this year, these energy-guzzling AI complexes have contributed towards a 7 percent rise in the average American electricity bill. And it is predicted that suppliers will struggle to keep up with demand as larger, more power-hungry sites are built.

Calculations by the International Energy Agency suggest that data centres already account for 1.5 percent of the world’s electricity consumption. This demand has grown at a rate of 12 percent per year since 2017, and is expected to increase by more than double by 2030, straining electricity grids.

In many cases, Big Tech firms are constructing dedicated power sources for their data centres. Nevertheless, by some estimates, depending on chip efficiency, the total shortfall in the US grid by 2030 could be anywhere between 17GW and 62GW – equivalent to around 2-5 percent of present capacity.

The squeeze is not constrained to the US economy, however. AI mania is pulling in capital from across the world. This makes it harder for smaller nations – including relatively advanced capitalist countries like Britain – to attract investment at home, forcing up bond yields (government borrowing costs).

The overall effect of the AI bubble, then, is to distort the entire economy; to pile contradictions upon contradictions within the capitalist system.

We are frequently told by the apologists of capitalism that the free market is the most efficient mechanism for allocating economic resources – such as capital and labour – across society.

But the monstrous deformations created by the AI boom (and eventual bust) show that this is far from true.

The only thing the capitalist market is ‘efficient’ at is lining the pockets of the billionaires, bosses, and banks. By all other measures, it is anarchic, destructive, and hugely wasteful.

In the short-term, the tech sector is suffocating the rest of the economy, parasitically siphoning up productive capacity that could otherwise go towards genuinely useful ends.

AI zealots promise that the technology will bring previously unseen productivity gains and growth, bringing forth a new golden age. Instead, money and resources are potentially being thrown into a black hole, while urgently-needed services and infrastructure crumble.

In the long-term (or potentially quite imminently), when the bubble bursts, it will leave behind permanent scars: a wasteland of scrap metal, tumbleweed, and silicon-stuffed husks; and, even worse, a domino of defaults – a contagious crisis that spreads from industry to industry, pulling the whole of society into a quagmire.

Parallels with the past

With its epicentre in Silicon Valley, today’s AI frenzy has drawn understandable comparisons with the dot-com bubble of the early 2000s, which ended in tears for numerous startups and shareholders alike.

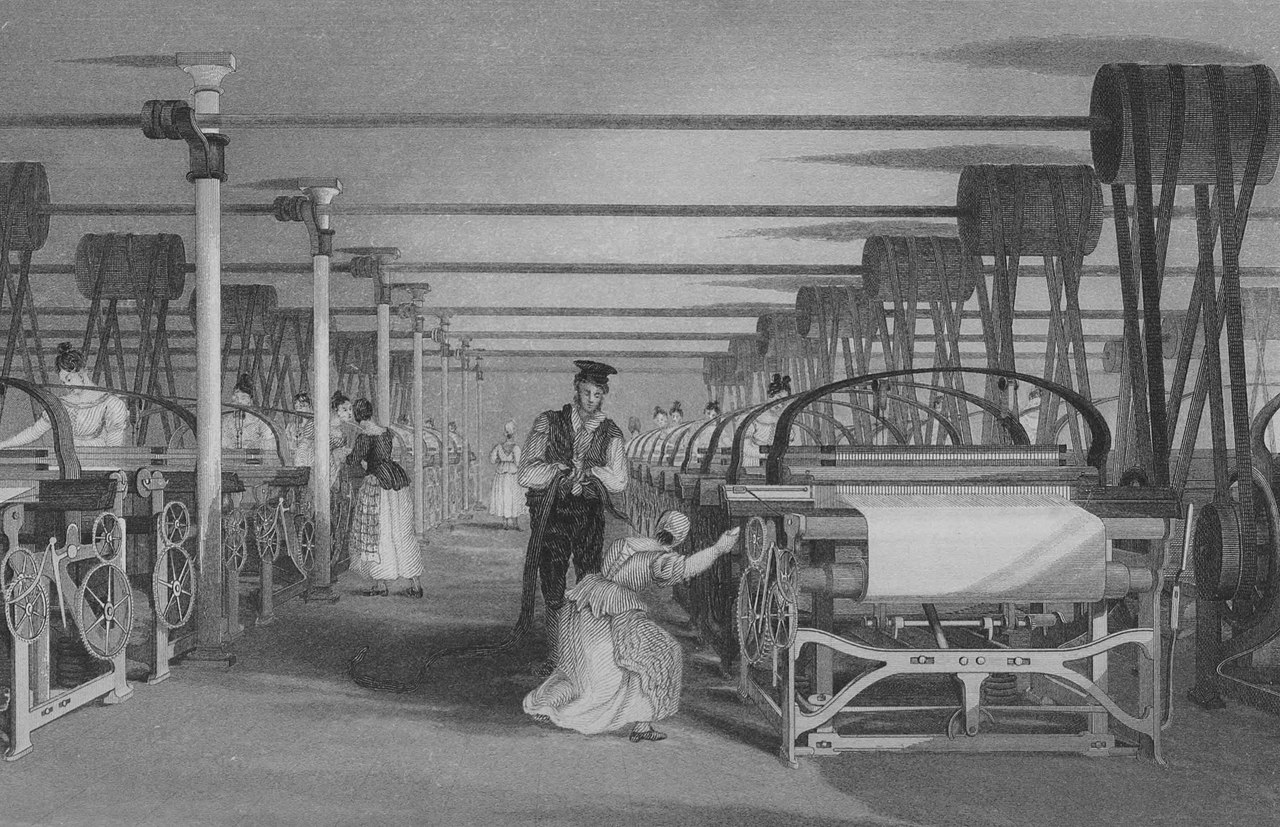

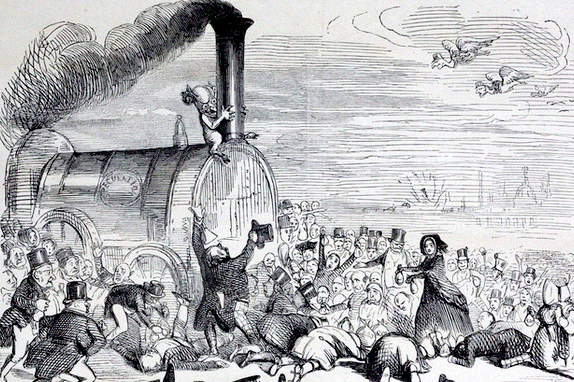

With its hyperactive infrastructure investment, however, and its potential to wreak havoc on the wider economy, a more appropriate historical analogy might be the rail bubble of the 1840s.

As with AI today, the buildout of the railways in 19th-century Britain – replacing the country’s canal network as the primary mode of transport for industry – came with all manner of hysteria and speculation.

The railways, like AI or any other new technology, had a genuine utility to society. But left to the ‘invisible hand’ of the market, their introduction and implementation was accompanied by a tremendous, wasteful bubble.

Lured by the prospect of juicy profits, investors piled into the booming industry, grabbing shares in the proliferation of newly-established private rail companies that were promoted.

In 1844, Parliament passed the Railways Act and set up a national ‘Railway Board’, with a remit to scrutinise proposals for new lines. The aim was to avoid duplication and excessive competition, and ensure that the country’s rail network was rational and integrated.

State regulation could not withstand the pressures of the market and the demands of investors, however. The Railway Board was initially ignored and later – within a year – disbanded.

Anarchy soon reigned. This led to “a mad rush of railway schemes being developed for parliamentary approval in the 1846 session”, according to authors William Quinn and John D. Turner in their book Boom and Bust – A Global History of Financial Bubbles.

Rail companies’ share prices ballooned, doubling between 1843-45. But this was clearly unsustainable. Intense competition was pushing profits down across the sector. Few of the lines proposed were economically viable.

In many cases, rail firms’ owners were paying out dividends using incoming capital from new stock buyers, not from actual profits – almost the definition of a Ponzi scheme.

Nevertheless, the euphoric mood – fuelled by loose monetary conditions at the time, and by fear of missing out – helped to maintain the bubble.

Historically low interest rates, reduced to just 2.5 percent by the Bank of England in September 1844, encouraged wealthy investors to search for higher yields on riskier assets. This included taking a punt on nascent, unproven rail firms.

The ability to ‘part-pay’ for rail stocks (with just a 5 percent deposit needed to buy up shares), meanwhile, made entrance to this veritable casino affordable to the middle classes. This widened the scope for speculation.

Like with the latest tech bubble, the rail industry came to dominate the stock market and suck in wealth from across the land. According to Quinn and Turner, in 1838, railway shares made up 23 percent of the total value of the stock market. A decade later, this figure stood at a staggering 71 percent.

“From 1844 to 1847”, meanwhile, The Economist reports, “investment rose from 5% to 13% of British GDP.” Elsewhere, the same journal estimates that “British railway investment in the 1840s was 15-20% of GDP”.

Eventually the bubble began to burst. The mainstream press, having initially helped to whip up investor optimism and hype, started to question some of the rail proposals that were being promoted – and, in turn, the prospects for the industry as a whole.

As construction began on all these lines, the exaggerations and outright fraud of the rail companies and their directors became clearer. Shareholders were asked to hand over ever-more cash as projects went over-budget. This provided a cold reality check for investors. Promises of super-profits were evidently never going to be realised.

Just as easy money had helped to inflate the rail bubble, it was a monetary tightening that helped to bring about its deflation. Interest rates began to rise from October 1845. The Irish potato famine – beginning around this time – was an important factor in this, forcing Britain to import more food from beyond the borders of the Empire, leading to an outflow of gold.

As cheap credit dried up, the scale of the gambling became more apparent. In the words of contemporary billionaire investor Warren Buffett: “A rising tide may lift all boats, but only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

By the end of 1845, rail share prices had plateaued. And by the summer of 1846, they were starting to go into decline. “When it finally reached its bottom in April 1850,” Quinn and Turner state, “the market for railway shares had fallen 66 percent from its peak of the summer of 1845.”

The widespread extent of the speculation across society meant that the fallout from the rail bubble was devastating. Not only rich investors but middle-class shareholders also were hit. Investment fell by half and unemployment doubled.

The demands for capital from the rail companies, meanwhile, added to the pressures in the financial system. This led to a financial panic breaking out in Britain in 1847.

Rail companies began to go bust. Others merged and combined in order to achieve profitability. Meanwhile, construction on unviable rail projects was rapidly wound up.

According to Alasdair Nairn, in his book Engines that Move Markets, “nearly 20% of the track authorised for construction was abandoned”. On top of that, Quinn and Turner note, “a further 2,000 miles, worth about £40 million of capital, were abandoned before Parliament’s formal consent had been granted”.

In other words, although vast distances of track were laid, huge amounts of capital and labour were ultimately wasted due to the anarchy of the market. As Nairn concludes:

“In aggregate, over a very long period of time, there is no question that, for all their economic impact, the railways provided negative returns, whether you measure that in real, relative, or absolute terms. This illustrates the general truth that in the aftermath of any period of speculative excess, when companies are funded on the expectation of instantaneous stock market returns, huge amounts of capital are wasted on non-economic projects.”

Quinn and Turner also highlight the contrast with the buildout of the railway network in France and America.

In these countries, there were far greater levels of state control over rail construction. Competition was regulated; duplication was avoided; and rationalisation was thereby largely achieved. Consequently, unlike in Britain, there was no associated bubble and much less waste when it came to building a nationwide rail system.

In Britain, however, Quinn and Turner conclude, the paradoxical logic of the market led to massive inefficiencies – the impact of which we are still experiencing in the 21st century:

“The inefficiencies in the rail system that were locked in during the Railway Mania contributed to the subsequent poor performance of the railway companies and widespread inefficiencies which have plagued British railways down to the present day. Thus, rather than the bubble being useful for society, it created a higgledy-piggledy network and a railway system full of long-term inefficiencies. In addition, too much investment was wasted in building this sub-optimal network.”

The parallels with today’s AI infrastructure investment are clear.

Speculation, overproduction, and revolution

Marx and Engels wrote a retrospective analysis of the 1840s rail bubble, which they described as the ‘Great Railway Mania’.

“The heyday of this speculation was the summer and autumn of 1845,” they outlined. “Stock prices rose continuously, and the speculators’ profits soon sucked all social classes into the whirlpool.”

“Dukes and earls competed with merchants and manufacturers for the lucrative honour of sitting on the boards of directors of the various companies; members of the House of Commons, the legal profession, and the clergy were also represented in large numbers. Anyone who had saved a penny, anyone who had the least credit at his disposal, speculated in railway stocks…

“On the basis of the actual extension of the English and continental railway system and the speculation which accompanied it, there gradually arose in this period a superstructure of fraud reminiscent of the time of Law and the South Sea Company.

“Hundreds of companies were promoted without the least chance of success; companies whose promoters themselves never intended any real execution of the schemes; companies whose sole reason for existence was the directors’ consumption of the funds deposited and the fraudulent profits obtained from the sale of stocks.”

Marx and Engels emphasised, however, that this speculation was not accidental, due to mere investor madness or herd behaviour, but was symptomatic of deeper contradictions within the capitalist system – above all, the contradiction of overproduction.

“As is always the case, prosperity very rapidly encouraged speculation. Speculation regularly occurs in periods when overproduction is already in full swing. It provides overproduction with temporary market outlets, while for this very reason precipitating the outbreak of the crisis and increasing its force.

“The crisis itself first breaks out in the area of speculation; only later does it hit production. What appears to the superficial observer to be the cause of the crisis is not overproduction but excess speculation, but this is itself only a symptom of overproduction.

“The subsequent disruption of production does not appear as a consequence of its own previous exuberance but merely as a setback caused by the collapse of speculation.”

– Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Review: May-October 1850 in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (our emphasis)

Moreover, they explained how, when the rail bubble burst, it combined with other economic turmoil and political fragility to set off a chain reaction of crisis and revolt across Europe, culminating in the 1848 revolutions.

Capitalist contradictions

This provides valuable lessons for understanding today’s perspectives.

As in the 1840s, we are living through an era of instability and uncertainty. A mountain of combustible material is accumulating across the world, just awaiting a spark to set it ablaze. And there is no shortage of candidates for what could eventually ignite this tinderbox.

Like the speculation in rail stocks that Marx and Engels wrote about, the AI bubble is but one of many symptoms of the contradictions building up within the global economy; of the senility and impasse of the capitalist system.

With markets saturated (and shrinking), and few other opportunities for profitable investment in the real economy, the capitalists are stampeding into tech, in the hope of getting rich quick.

This frothy frenzy and folly is by no means confined to the tech industry. Whether it be real estate or gold; crypto or ‘NFTs’: an orgy of speculation has been seen in recent years, as trillions of fictitious capital (i.e. money printing and credit) – pumped into the global economy by the ruling class to save their system – hits up against limited markets and profitability.

On top of this speculation, meanwhile, we now see a host of other distortions and tensions being added to the world economy, including those created by protectionism, debt, and rearmament.

A whole era of cheap credit and easy money provided the fuel for these asset bubbles. Notably, however, today’s mania around AI is taking place at a time of tighter monetary policy, with interest rates remaining heightened compared to the rest of the previous (post-2008) period.

This highlights that the underlying, deeper problem is that of overproduction: the abundance of capital in the hands of the bankers and billionaires, looking for a profitable outlet; the inability of the capitalists to produce and sell at a profit.

Put simply, the productive forces – society’s capacity to produce; its level of industry, technology, and science – have vastly outgrown the straightjacket of the capitalist market.

Catastrophic consequences

The evidence provided shows that a crash in the tech sector clearly has the potential to be the trigger for a wider economic avalanche. And given the dominance of Big Tech and its shares, the damage could be catastrophic.

The bursting of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s helped to provoke a slump in the stock market and push the US economy into recession. Since then, however, the contradictions in the capitalist system have magnified a thousand fold.

Above all, there is far more debt and fictitious capital sloshing around the globe nowadays.

A report by McKinsey, for example, estimates that nearly 60 percent of the growth in American household wealth over the decade-and-a-half has been “on paper, stemming from asset price growth rather than saving and investing”.

Similarly, the amount of ‘wealth’ wrapped up in stocks is 50 percent greater relative to the size of the economy than it was at the time of the dot-com crash. And the proportion of households holding their savings in shares has rocketed. Today, ordinary Americans have around $42 trillion in US stocks – around 21 percent of their total wealth.

Overall, meanwhile, private and public debt in the US has increased from nearly $30 trillion in 2000 to over $100 trillion today.

Consequently, according to the calculations of former IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath, “a market correction of the same magnitude as the dot-com crash could wipe out over $20trn in wealth for American households, equivalent to roughly 70% of American GDP in 2024.”

For comparison, state support during the pandemic in America amounted to around 25 percent of US GDP. And the trillions thrown at the banks during the 2007-09 financial crisis equated to more than half of US GDP at the time.

In turn, The Economist estimates that a tech bust such as this could destroy 8 percent of the wealth of ordinary families in the USA. This would likely cause household consumption to contract sharply, adding to the economic hit coming from the sudden withdrawal of any AI-related investment.

“This is several times larger than the losses incurred during the crash of the early 2000s,” Gopinath continues. “The implications for consumption would be grave…translating into a two-percentage-point hit to overall GDP growth, even before accounting for declines in investment.”

Furthermore, “the global fallout would be similarly severe,” Gopinath writes. “Foreign investors could face wealth losses exceeding $15trn, or about 20% of the rest of the world’s GDP.”

Other estimates suggest that an equivalent sized collapse to the dot-com crash could wipe $40 trillion off the value of the stock markets.

Given the enormous existing levels of debt in the world economy, the heightened tensions between the big imperialist powers, and the political gridlock in the US and Europe, meanwhile, Gopinath correctly emphasises that the ruling classes would struggle to decisively respond to a serious new slump.

“In sum,” the economist concludes, “a market crash today is unlikely to result in the brief and relatively benign economic downturn that followed the dot-com bust.”

“There is a lot more wealth on the line now – and much less policy space to soften the blow of a correction. The structural vulnerabilities and macroeconomic context are more perilous. We should prepare for more severe global consequences.”

We, as communists, meanwhile, should prepare for revolutionary explosions – and build our forces with a sense of urgency.

For socialist planning

There are, then, a number of similarities between the Great Railway Mania of the 1840s and the AI bubble. But there are also important differences.

The former occurred in an era when capitalism, as a socio-economic system, was still relatively young and healthy – capable of recovering from its crises, and developing the productive forces.

Nowadays, however, we are living through a seemingly neverending, organic crisis of capitalism. The economy has been stuck in a morass since the 2008 slump. Productivity and growth – and, in turn, living standards – have stagnated. The system is at a dead-end.

As Marxists, we are not Luddites. We want to see the maximum levels of automation across the economy, in order to free humanity from the toil and drudgery of labour.

This would lay the material basis for men and women to fulfill their full potential, allowing creativity and culture to flourish.

Under capitalism, by contrast, machinery and technology does not liberate us, but enslaves us. The anarchy of the market, meanwhile, leads not only to economic inefficiency and waste, but to a squandering of human potential.

Instead of bringing the greatest minds together to collaborate, innovate, and advance science, talented techies (and workers in general) are forced to compete with one another – and with the fruits of their own labour: the technology that they create.

In turn, these fruits – socially produced – are privately appropriated by the capitalists; turned into the mega-profits of the Big Tech bosses.

We want to develop technology and harness the power of AI. But we want to do so in a rational way, in the interests of the billions, not the billionaires.

All of this highlights the need for socialist planning, as the only way to harmoniously develop the productive forces – of technology, science, and industry – and take society forward.

This can only come about on the basis of a socialist revolution, to overthrow the crisis-ridden capitalist system and put the means of production – the main levers of the economy – in the hands of the organised working class.

This brings out another important difference between now and the 1840s. Compared to Marx’s time, the objective conditions for socialism and communism are far more favourable today.

The industrial and technological basis for economic planning and workers’ democracy exists on a world scale. The working class has never been stronger.

What is missing, above all, is the subjective factor: the revolutionary leadership that can help bring the working class to power.

We are living in an epoch of revolution. The deepening crisis of capitalism is transforming consciousness, leading to social upheavals in one country after another.

And just as the rail bubble acted as a starting pistol for the 1848 revolutions, so too could a bursting of the AI bubble be the straw that breaks the camels back when it comes to the revolutionary movements of the working class today.