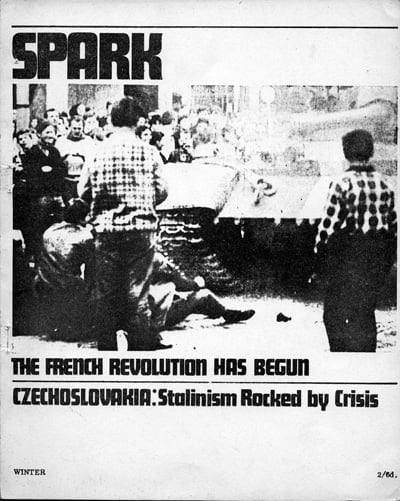

The general

strike in France earlier

this year has shattered the complacent attitude of the representatives of the

capitalists in Western Europe, and of the

reformists and those in the Labour Movement who believed that the so-called

“affluent society” had rendered Marxism obsolete. In the Western world, as a

result of the economic upswing since the war, they had claimed, classes and

class concepts as understood in the past were no longer relevant to a society

which had solved the problems of capitalism. Slumps and class struggle were a

thing of the past. With the pressures of capitalism, their bureaucratic

structure, and their history, the Stalinist parties became even more

bureaucratically degenerated than the parties of the Second International. All

these factors, together with their isolation from the masses, in their turn led

to a mood of pessimism and despair by the “Marxist” sects claiming to represent

the ideas of Lenin and Trotsky. They developed a sceptical attitude towards the

revolutionary potential of the working class of the Western capitalist

countries. They viewed the possibility of socialist revolution in the West as

ruled out for decades. They sought salvation in the upsurge of the colonial

world, finding in the peasants of the under-developed world the new

revolutionary class which would solve the problems of the revolution.

In other

articles and pamphlets we have made an analysis of this perspective pointing

out its falsity and inadequate understanding of the processes taking place in

the capitalist world. Analysing the process taking place in the main capitalist

countries we forecast the inevitability of sudden and abrupt changes which

would alter the relationship of forces between the classes and end the foetid

and poisonous atmosphere in which Marxists have been forced to work for almost

a generation.

Such a change

is the “May revolution”, as bourgeois commentators have named it, in France. France is the

“classical country” of the class struggle. It is rich in movements of the

workers and of the French people beginning with the bourgeois revolution in

1789, and the following revolutions, culminating in the Paris Commune. It is

the country which first established bourgeois bonapartism or the

military-police capitalist state. It has seen a succession of regimes,

revolution being followed by counter-revolution, and again being followed by

revolution.

After the

experiences of the Commune, the cowardly French bourgeoisie preferred to invest

their capital in the colonies or abroad, and keep the working class, with its

great traditions, as a minority of the population. They continued this policy

between the wars, relying heavily on their Empire and “usurers capital”. The

world slump of 1929-33 affected them later and hit them harder. This prepared

the way for the forerunner of the May upsurge, the stay-in strike of 1936,

which was betrayed by the “strike-breaking conspiracy” of the Peoples’ Front.

Again, as in previous movements of the French people, analysed by Marx in the 18th

Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, the cowardice and treachery of the “petit

bourgeois democrats” prepared the way for reaction, the demoralisation of the

French people, the victories of Hitler and the occupation of France in the

Second World War.

Rather than

face the danger of a second Commune, the French ruling class preferred to

surrender to the Nazis. The events of the Second World War regenerated the

movement of resistance among the French working class and the French people

generally. The members of the Communist Party were in the front rank. The mass

of the population had a mood of violent revulsion at the collaboration between

the ruling class and the occupying Nazis. Once again the leaders of the

Communist Party and the Socialist Party collaborated in a “National” or

“coalition” or Popular Front Government in the post-war period. Lenin all his

life had fought against such a concept. He stood for the independence of the

working class from all capitalist parties. The winning of the working class and

the other strata of the middle class by fighting for their interests and

drawing them away from their capitalist exploiters was central to his whole

approach.

The powerful

post-war upsurge was crushed by the policy and tactics of the Communist Party

leadership. They used their regained prestige, due to the heroic efforts of the

rank and file, to save French capitalism from destruction. Their argument at

that time was the “danger of a Third World War” if capitalism in France was overthrown.

They remained in the Government of De Gaulle which massacred their Vietnamese

comrades in Saigon and Hanoi, which conducted

the war of intervention and which broke strikes and the movement of the

peasants in France.

When they had done their dirty work, together with their comrades in the rest

of Europe, American Imperialism and its satellites fell out with the Moscow bureaucracy and

the “cold war” began. On the instructions of Stalin they posed as

“irreconcilable revolutionaries”. Also at that stage they were haunted by the

fear of being outflanked from the “Left”. They began a movement of

“opposition”. They were thrown out of the Government and then indulged in all

sorts of wild adventures. But the working class is not a tap which can be

turned on or off at the whims of bureaucrats. Their policies had demoralised

the workers, and whereas in 1944-47 they could call demonstrations in Paris alone of a million

people, they were fortunate to get hundreds at their anti-American

demonstrations.

At the height

of the war against the Algerian people, the Communist Party offered only

passive opposition. The failure of the Communist Party leadership to give an

internationalist lead led in its turn to the Algerian struggle taking a purely

nationalist form. This drove the white settlers into the arms of fascist

reaction. Thus the opportunity was created 10 years ago for the rise of a new

Bonapartism in the form of General De Gaulle. For this the Communist Party

leadership and that of the Socialist Party had a great responsibility (See: Ted

Grant, “France in Crisis”, May 1958).

The last

decade, under the regime of “personal power” witnessed the fast

industrialisation of formerly backward France. The privilege of

backwardness was ended with the Second World War, the revolt of the colonial

peoples, and the further development of competition on world markets. The

French bourgeoisie was compelled to try and modernise the economy for French

imperialism to maintain even a secondary role in the world. The ruined peasants

streamed into the towns, foreign workers were employed by hundreds of thousands

on the worst and most unskilled jobs, and French industry leaped forward. But

the benefits of this increased production were very unevenly shared. While the

standard of living, especially of the more skilled workers, rose absolutely,

their share of the increased production dropped.

It was in

this atmosphere that the student revolt developed. This was a symptom of the

malaise in society. The sons and daughters of the middle class, upper middle

class, and even of the bourgeoisie were in revolt against the rotten values of

the ruling class. This movement is a symptom of the crisis in the capitalist

world. The demonstrations of the students were viciously attacked by the picked

riot police of the C.R.S., notorious for their thuggery and brutality. The

beating up of demonstrators only inflamed the students even more and led to the

outbreak of fighting on the barricades in the Latin Quarter, the seizure of the

universities in Paris and then throughout France. This in its turn led to a

movement among the secondary school children.

The

leadership of the Communist Party, haughty and solid bureaucrats through and

through, denounced the students in hysterical terms, as “adventurists”,

“provocateurs” and “ultra-lefts”. While undoubtedly there were many

effervescent and confused elements, the students marching under the red flag of

Socialism and the black flag of the anarchists, were instinctively striving to

find the road to a new society and to the working masses. The population of

France and especially the working class was stirred to a revulsion against the

regime by the sadism of the police in their attacks on the students.

The Communist

Party, the Trade Union leaders of the C.G.T., C.F.D.T. and Force Ouvriere, the

United Socialist Party, and the so-called Socialist Democratic Federation of

the Left which comprised the Socialist Party and remnants of some bourgeois

republican parties called a general strike. They felt the wind of anger blowing

within the masses and called for demonstrations. Ten million workers answered

the strike call and 800,000 to 1 million marched in the demonstration in Paris on May 13th.

At each time

of crisis this trick of a 24-hour general strike has been used by the Communist

Party leadership in the post-war period. “Let the masses let off steam” seemed

to be their philosophy, “Everyone will be satisfied, and we can then return to

the old game of declamations and parliamentary speeches and show our

r-r-r-r-revolutionary spirit of opposition now against Gaullist personal rule.

In time the way will be prepared for a new version of the Popular Front, the

workers will have done their duty, and then everything would return to

‘normal’.”

This time it

was not to be. The atmosphere had been too charged with the electricity of

discontent. The accumulated resentments of a generation of capitalist reaction

were coming to a head. Beginning with the aviation workers, in one Sud Aviation

factory, then the car workers at Renault, the workers in one industry after the

other began the seizure of the factories. Workers on the railways, metro,

buses, in engineering, coal, chemicals, steel, marine, shipyards and ships, and

in other industries occupied their factories. Within days the movement had

spread to the white collar workers, the teachers and professors, the big

offices, the banks and post offices, sorting offices, the labour exchanges,

even the Observatories, the department stores and insurance offices. Ten

million industrial and white collar workers were on strike. In the last stages

the agricultural workers and peasants and the clerical staff of the prefectures

came out on strike or joined the movement. If the electricity, gas and water

workers did not come out it was because while they were refusing to supply

industry they did not want to cut off electricity, gas and water from the homes

of ordinary people, under the demagogic appeals of their “leaders”.

In contrast

with the general strike of 1926 in Britain, this was a spontaneous

movement of revolt from the bottom. It was the young generation of workers in

the factories, not burdened with the cynicism engendered by the betrayals of

the past who initiated the movement. It was in the spirit of the great

traditions of the French working class and of the French people. Symbolic of

the mood of the workers were the red flags flying over the factories, labour

exchanges, department stores, ships and offices. It was the greatest strike movement

in the history of the working class. All the more significant is that one wave

after another of the industrial and white collar workers joined in without any

lead from above. Factories which had been unorganised, or as with Citroën had

“company unions” and armed guards to keep out “agitators” or union organisers,

joined the rest of the working class. The white collar-workers demonstrated the

same militancy as their industrial brothers. The “State” was paralysed! At the

height of the struggle even the police showed that they were unreliable! This

included even the reactionary C.R.S., who had been used with great brutality

against the student demonstrations and were then made the scapegoat. The Police

Federation went further and issued a declaration that they were in sympathy

with the demands of the workers and had similar grievances of their own.

De Gaulle had

announced a plebiscite on the radio and television. But the printers refused to

print the forms! Attempts to get the forms printed in Belgium failed.

The Belgian printers, demonstrating international solidarity, refused to

blackleg against their French brothers. The mighty Bonapartist state—the “Strong State”

which had been depicted by some revolutionaries—was impotent.

Had the

“Communist Party” been a revolutionary movement the power of the capitalist

class would have been broken. The main task was the linking of the factory

committees, locally, regionally and nationally. This would have given the

latent power of the workers structure and form. To the workers’ committees

could have been joined those of the students, peasants, housewives, small

businessmen, the army, and in their mood then, even the police. This was the

situation which called for “audacity, audacity and again audacity”. In Italy, in America,

in Britain, in West Germany, in fact the entire Western World,

the capitalists viewed with horror and dismay the beginning of the Socialist

Revolution in France.

An irony of history: the bourgeoisie of the entire Western World saw as their

only consolation the fact that the Communist Party leadership was a force of

conservatism and had become a party of order. The Russian bureaucracy and its

satellites were busily denouncing as a slander conjured up by the world

bourgeoisie the idea that France

was in a revolutionary crisis.

In the words

of Trotsky, the Stalinists in France

“put the thermometer under the tongue of old lady history and decided that the

situation was not revolutionary”.

It is

necessary under these conditions to use the ideas of Marx and Lenin in order to

expose this cant. To these gentlemen we say, “What is a revolutionary

situation?” Answering the same cowardly attitude by Plekhanov, who said in 1905

that the workers should not have taken up arms “when the situation was not

revolutionary”, Lenin, echoing Marx, analysed carefully, the conditions for

revolution. The first condition is the vacillation and split in the ruling

class. Who can deny that during the height of the May events there was panic in

the ranks of bourgeoisie reaching up even to the pinnacle of power, with the

demoralisation of the Bonaparte De Gaulle? The second condition is the wavering

of the petit bourgeoisie looking for a way out either from the workers or the

capitalists. As Lenin explained, with a firm policy from the working class,

under these conditions, they would win the support of the middle class. The

third condition is the readiness to struggle on the part of the working class.

Who can deny the readiness to fight of the French workers as shown by the spontaneous

movement after the token strike called by the Left parties and all the Trade

Union Federations? In the past this harmless manoeuvre had succeeded in

preventing the workers from moving into action. But not this time. As sketched

above, layer after layer of the proletariat and white collar workers and even

the peasantry moved into action. The truth is that it was the fourth condition

outlined by Lenin which was absent. This was a mass revolutionary organisation

with a far-sighted revolutionary leadership which was democratically controlled

by the workers and ready to take the boldest steps to achieve the victory of

the working class.

How

degenerate these gentlemen have become over the decades of Stalinist crimes! In

France and the other

countries of Western Europe the leadership of

the so-called Communist Parties had become integrated into the structure of the

old society. On a higher level we have a repetition of the crime of the social

democratic leaders which saved capitalism after the First World War. The

bureaucrats in Moscow, who have now developed

arteriosclerosis living their nice comfortable existence, were even more

terrified than the capitalists in the West at the spectre that they thought

they had laid of a new and higher version of the October Revolution, this time

in industrial France.

“The

situation was not revolutionary!” Just consider how Lenin castigated the

Italian reformists in 1920 at the time of the seizure of the factories by the

Italian workers. The Italian socialist leaders too, trembling before the action

of the working class, declared that the situation was not revolutionary. How

Lenin scorned and reviled these “traitors”. What would he have said about such

a magnificent movement as that of the French workers, a hundred times as great

in its scope, in its depth, and in its paralysis of the forces of capitalism

and their state? And yet in this situation all that the so-called Communist

Party leadership does is to plagiarise all the worst features of the reformist

leaders. All the leaders of the Communist Parties of the world are dragging out

the distorted quotation from Engels, against which Engels himself complained,

and of which Lenin wrote in acid terms in his polemic against Kautsky and the

“Left reformists” and “heroes of the Second International”. Lenin had so

painstakingly refuted this vile trick of pretending that Engels in his old age

had become a mild reformist. Alas, alas, Palme Dutt, always ready to eat his

words in the interests of the Stalinist apparatus, and echoing the revolutionary

romanticism of his youth, had written in May—before the events—in the

journal of the so-called international Communist Movement an indignant

criticism of denigrators of Engels who used this very quotation, lamenting that

Marx’s “far-sighted warning…against the danger of the trend of petit-bourgeois

reformism…or the anger of Engels over the falsification of [the] 1895 Preface

to the Class Struggles in France” were ignored. (World Marxist Review,

May Issue)

Waldeck

Rochet and all the epigones of Communism try and argue that it was only a

movement for higher wages and better conditions. What was the October

Revolution but a struggle for “Peace, Bread, Land”? But the problem for the

Communist Party, like the Bolsheviks in Russia, was to link up the demands

of the masses with the need for the Socialist Revolution. Our new reformist

heroes try to prove too much. If it was “only” a struggle for better conditions

and wages why did the Communist Party issue a declaration by Waldeck Rochet in

a special edition of their organ, L’Humanité which said:

“Millions of manual

workers and intellectuals are on strike, the aspiration of all the people to a

real change of regime does not cease to grow…on the political plane the problem

of power remains more than ever posed. The Gaullist regime has outworn itself.

It must go. To achieve the aspirations of the workers, of the teachers, of the

students it is necessary that the State ceases to be a tool of the monopoly

capitalist…That is why the French Communist Party considers that it is

necessary to take a step towards Socialism, proposes not only the

nationalisation of the big banks but of the great monopoly industrial

enterprises which dominate the key sectors of the economy.”

The leaflet

goes on to say that the Communist Party stands for the “democratic control of

the national enterprises and the establishment on all layers of economic life

of workers control; to begin by the extension of the role of the factory

committees and the free activity of the Trade Unions in the enterprises…it is

necessary to end the power of the monopolies and with it the Gaullist power and

to promote a popular Government leaning on the support of the people.” What is

this all about? If the workers were only interested in wages and conditions at

a time when the Gaullist regime was cracking and under the pressure of the

working class why did the Communist Party distribute this declaration

throughout France?

One thing or the other—either the situation was revolutionary, or the Communist

Party leadership was guilty of cynical demagogy.

“Ah…” say the

faint hearts, as they have always said before every revolution, “What about the

Army?” Waldeck Rochet explains profoundly that they did not want to send the

workers to be crushed by the tanks of Massu. In the Morning Star the

Editor of L’Humanité also wrote on the danger of the armed forces. That

new Vicar of Bray, Palme Dutt, wrote in the Labour Monthly the opposite

of what he had written a few months before and denounced the “ultra Lefts” for

light-mindedly forgetting the “menace of the Army”. As usual he finds a

convenient quotation against the frivolity of the anarchists, while forgetting

that in the very same material Lenin protected his rear against sophists like

Dutt by his implacable criticism of opportunism. But let us examine this

question of the army a little closer. De Gaulle visited Massu after the

collapse of his attempt at a referendum. The “personal power” against which the

Stalinist leaders are always railing rests not only on elections but on the

army and police. It was allegedly fear of the army, which would crush the

workers, that paralysed the leadership of the Communist Party. One can then ask

these parliamentary cretins: if the capitalists could use the army before the

elections, why not after a “democratic victory” at the polls? In

reality, as the Times clearly explained, to try and use the army would

be to break it. In every revolution the attempt of reaction to use the army,

which is composed of workers and peasants, will split it from top to bottom. It

is true that a revolution can be defeated, but when one has a situation like

that in France

with a complete paralysis of the State then the issue can be decided by the

quality of the leadership of the working class.

How gladly

the leadership of the Communist Party seized on the Gaullist trick of the

dissolution of the Assembly and elections. Then in order to keep up with their

“allies” in the tops of the so-called Left Federation and in order not to

frighten away the lawyers and professional politicians, who provide an

alternative face for the bourgeoisie, they dropped the very radical demands

listed above. In order to show themselves as respectable and not the famous

wild man with a knife between his teeth they tried to compete with the Gaullists

as a party of “Law and Order”.

When the

party of the working class, or more correctly the party claiming to represent

the working class, tries to compete with the representatives of tie bourgeoisie

on this level they are asking for a defeat. Had the Communist Party fought the

elections on the programme as outlined in the Declaration of Waldeck Rochet and

at the same time made a determined effort to win over the middle class and

peasantry by a programme catering for their needs—had they emphasized that the

needs of the workers and the people generally could only be satisfied by the

overthrow of capitalism and a change in society—they would not have suffered a

defeat at the polls.

However, the

elections demonstrated the polarisation in France of class forces; the working

class and its parties on the one side and the bourgeois parties clustered round

Gaullism on the other. The fact that the P.S.U., Party of Socialist Unity,

which stood to the left of the Communist Party gained half a million votes, while

the Communist Party itself lost six hundred thousand is significant. However,

while there were ten million strikers in the country, the left parties only

received nine million votes. Where did the other million go? It is clear that

many strikers together with their wives must have voted for the bourgeois

parties and even the Gaullists. That was the penalty paid because of the policy

of the Communist Party.

The elections

marked a victory for reaction in France. While the cretins of the

Communist Party were putting their faith in the elections, all the bourgeois

observers were pointing out that the election results were secondary as far as

the movement of the masses in France

were concerned.

However, the

immediate effect was undoubtedly a fall in the spirit of the masses. The

Communist Party has used the election results as a justification of the idea

that there was no revolutionary situation in May.

In fact, they

are responsible for electoral defeat and the immediate change in the situation

which it has provoked. The Communist Party leadership is silent in Britain and

other countries on the results of the immediate psychological defeat for the

working class. The “Patronat” have taken revenge for the fright which the

events of May had given them.

Tens of thousands

of militants in the factories and enterprises, in the technical institutes and

white collar trades have been victimised. A real witch-hunt has taken place in

the factories on one pretext or another.

Here it is to

be noted that the C.G.T. gained a modest four hundred members, while its rival

the ex-Catholic federation, C.F.T.D., doubled its membership by gaining

one-and-a-half million members during the May events, and it is now bigger than

the C.G.T. Together with Force Ouvrière the trade unions must now number over

six million, although in the French tradition, tens, even hundreds of thousands

of workers will tend to drop out of the unions in disgust when they see their

gains in the great May events being whittled away. Already the trickery of the

employers, the measures of the state, inflation, and all the other effects of

the underlying crisis of the capitalist system in France have partially wiped out the

gains. At the same time the small businessmen and the peasants will be also

affected. Tens of thousands of small businessmen will become bankrupt. Hundreds

of thousands of peasant small holders will no longer be able to make a living

and be driven into the cities. The unemployed and the youth will become further

disaffected. The students will find that there are not enough jobs in the

professions.

The election

results mark a temporary set back in the movement of the working class and the

people of France,

towards the Socialist Revolution. It has given time for the capitalist reaction

to consolidate itself. There will be a purge of police and a stiffening-up of

the ranks of reaction. Preparations will be made systematically in all of the

big towns to “deal” with the workers and students. But not even the Gaullist

election victory and the repression of militants in the factories will be able

to prevent a new surge forward of the French revolution at a later stage.

The situation

is analogous to that of the revolution in Spain of 1931-1936. In Spain, after

the fall of the Bonapartist dictator Primo De Rivera and the overthrow of the

monarchy, there was a Republican-Socialist coalition which broke strikes and

shot down the peasants when they tried to seize the land. This prepared the way

for the victory of the right wing Republican and Catholic Fascist reaction in

the elections. This in turn prepared the way for the Catholic-Fascist Gil

Robles to be taken into the coalition. Meanwhile, under the influence of

international events the Social Democracy in Spain

had evolved to the left and the reply to the inclusion of Catholic-Fascists

into the coalition government was the insurrection in the Asturias Province.

This was defeated and prepared the two black years (Bienio Negro) of

reaction in Spain.

This in its turn prepared the way for the onslaught of the workers ending in

the victory in the elections of the Popular Front in February 1936. There began

an uninterrupted movement of the workers and peasants against the liberal

Popular Front Government. There was one General strike after another in the

cities, one protest movement after another, of the peasants in the countryside.

To save themselves the capitalist class through the Generals launched the

conspiracy of July 1936, which culminated in the counter insurrection on the

part of the working class. It resulted in the smashing of the bourgeois state

in so-called Republican Spain. It would take us too far from the question under

discussion to deal with the reasons for the defeat of the Spanish Revolution of

1931-37, but the main factors were the policies of the mass workers’

organisations.

Of course,

events in France will not

develop in exactly the same pattern as those of Spain,

but Spain

provides a useful scheme of the process of the revolution. What has to be noted

is the process of swinging between upsurge and reaction, which takes place in

every revolution, and sometimes extends over many years. In Spain, it

unrolled over five or six years till we had the denouement of civil war.

In France, had the

Communist Party retained even a shadow of its revolutionary beginnings the

revolution would have assumed a peaceful character. It would have provoked a

wave of Socialist revolution throughout Western Europe and a political

revolution in Eastern Europe. The betrayal of

the Communist Party leaders makes the task of the overthrow of capitalism much

more arduous but it cannot prevent the movement of the working class to change

society.

A paradox of

the events lies in the fact that the very defeat caused by the Communist Party

will temporarily succeed in holding it together, as far as the mass of the

working class is concerned. The working class as a mass, though conscious of

its power in the May days, will be bewildered by the turn of events. The

propaganda of the Communist Party will have some effect. The workers and particularly

peasants and middle class will see that they have been fooled and panicked by

the propaganda of the Gaullists into voting for reaction. They will say it

would have been better if the Communist Party and the Left Federation had won

the elections. There will inevitably be a big swing of the masses in the

direction of Popular Frontism.

Of course it

is true that the most advanced layers in the factories, the militants of the

C.G.T., and many of the militants who remain members of the Communist Party,

will have had their eyes opened as to the counter-revolutionary role which is

played by the Communist Party leadership. Apparently, there are still many

action committees in existence in the factories, enterprises and districts.

These militants, especially the layer of young worker militants who led the

struggle, will later coalesce into some form of organisation. But at the

moment, they must understand that the vital need is that of patiently

explaining to the organised workers in the Communist Party, the P.S.U., the

Trade Union Federations and the other workers’ organisations in these events,

otherwise they will tend to become demoralised and despairing themselves. This

layer can only play a role in so far as they integrate themselves with the

masses and understand that the “May Days” were only the beginning of the

process of Socialist Revolution. Just as Lenin explained after the February

Revolution of 1917 that it was only the lack of consciousness on the part of

the Bolsheviks and the working class which prevented them from seizing power,

owing to the cringing of the reformists before the bourgeoisie, so the

Communist Party in France

played an even more perfidious role. But only future events and the inevitable

new upsurge on the part of the workers will make clear the role of the

leadership of the Communist party to the broad masses. Alas, it is only through

yet another experience of Popular Frontism and the victory of the Communist

Party and Left Federation in the elections that this will become clear.

At the

moment, where the revolutionary forces are very weak, the place where the

revolutionary militants should conduct their work is within the Communist

Party, the P.S.U. and the Trade Union Federations. But it is no use being in

the Communist Party and the other arenas of work if one conducts this work with

one’s mouth firmly shut. Even worse is the case where the work is conducted by

people hiding their ideas and making themselves as inconspicuous as possible by

assuming the colouration of the dominant trends within these organisations. To

pretend to be something for a long period, chameleon-like, is to become

virtually that thing itself. Only by boldly quoting the ideas of Lenin and even

the ideas advocated by the French Communist Party in the past, not by merging

with but by distinguishing the militants from the grey Stalinist and centrist

currents, can gains be made now and later.

It is not

excluded that if the economy in France

should continue on a higher level the upswing of the past period Gaullism might

temporarily succeed in stabilising itself. This would be especially so if a big

part of the gains of the workers should still remain.

At a later

stage with the discrediting of Gaullism the masses of the industrial workers,

white collar workers and even a big section of the small shopkeepers and middle

class will turn to the Popular Front as a way out. The coming to power of a

Popular Front will take place under entirely different conditions and with the

militants already aware of the role of the Communist Party leadership. The

classes will become more polarised even than they are at the present time.

Under the cloak of the Popular Front the capitalist class will seriously

prepare to settle accounts with the working class. Fascist organisations will

appear on the Right, armed and financed by big business. Under the blows of

reaction there will be a crisis in the Communist Party. Unable to “deliver the

goods” “on the parliamentary road” there will develop the long-postponed crisis

in the Communist Party. It will split from top to bottom. That is the music of

the future, however, at a further stage of the Revolution.

The main

problem of Marxism in France

today is that of convincing the layers of action committees of the C.P. and

P.S.U. and trade union militants, which at the moment largely represent a small

minority of workers, of the need for preparation for the struggles to come. The

fact that they have come to understand the real role of the Communist Party in

and of itself is not enough. They have to understand that to convince the

workers will require not only their heroic and self-sacrificing work in the

factories and Unions but their education in the basic ideas of Marxism. Then

they will be enabled to explain, with the help of events, at each stage how and

why the “Communist” Party is no longer a Communist Party.

It is

interesting to compare the role of the students in France

to that of the students in Germany.

Because the situation in Germany

has not yet reached the stage of social tension which it reached in France the

students did not make the same impact on the working class. In France the

movement of the students is in a sense the reflection, sometime in advance, of

the discontent of the social layers from which they spring: the upper and lower

middle class. Only 12 percent are of working class origins. The movement of the

students acted as a “detonator” of the movement amongst the masses. The May

events were not consciously prepared for by any tendency among the workers and

especially not among the students. There was no conscious preparation for the

magnificent movement that unfolded. But even without the movement of

students big strikes were already beginning to take place and could only

have culminated as in May or in 1936. The workers’ movement was inevitable. It

is to be noted that in 1936 it was the movement of the working class which had

certain echoes amongst the students and not vice versa.

The students

could play an important role as a leaven if they adopted a modest attitude,

tried to understand Marxism and the need to integrate themselves with the

working class. The danger at the moment in France consists in the fact that

the students through the mistaken ideas and perspectives of some of the leaders

of the left organisations may regard themselves as a substitute for the masses

and engage in adventurism which can only play into the hands of the leadership

of the Communist Party.

It must be

understood that the bourgeoisie in France, like the workers’

organisations, was caught by surprise by the May events. It came out of an

apparently cloudless sky. The movement of the students had the sympathy in the

beginning of most of the population. The repression of the C.R.S. which

received wide publicity aroused disgust and revulsion amongst the people. The

stirring of the masses, in its turn, prepared the movement of the workers. One

young worker told a Times reporter: “The students came first. They acted

as a spark. They caused the government to yield…They gave us the feeling that

we could go ahead.”

Thus as in

every Revolution where there is not a Marxist mass organisation, muddled,

confused and temporarily inflated elements come to the surface. Thus it is that

having rejected the stagnant conservatism of the so-called Communist party the

students’ revolt has unfortunately been coloured by the clouded ideas of

Marcuse, Castro, Guevara and Mao. Without the discipline of Marxist ideas the

students can inflict tremendous damage on themselves and on the movement as a

whole. The Gaullist regime is burning for an opportunity of revenge against the

students, whom they see as the instigators of their humiliation in May. The

police have made systematic preparations to brutally crush any attempts at the

setting up of barricades in the Latin Quarter and other university areas in France. From

anarchists, Maoists and Guevarists one could not expect that they would

understand that the problem in a highly industrialised country like France cannot

be solved by methods of guerrilla war, particularly in urban areas. The main

task in France as in other countries in the West and the industrialised

countries of the East is that of winning over the vast majority of the working

class and behind them of the people to understand that the mass organisations

no longer stand for the solution to the problems of modern society. There

is no substitute for this. The very process of winning and making conscious the

unconscious process in the minds of the workers is really the sum and substance

of Marxism. In the past Marxism has fought a bitter battle against all

varieties of anarchism, and “direct actionism” as well as against opportunism.

It was thus that Lenin and Trotsky explained to the Socialist Revolutionaries

in Russia,

as Marx had explained to the anarchists in a previous epoch, that the attempt

to replace the movement of the masses by irresponsible adventurism is suicidal

for the participants concerned and actually blocks the path to the winning of

the masses. In France

there is the tradition of Blanqui who was a martyr and fighter for socialism

but who imagined that a courageous minority could replace the masses. In a

somewhat modified form there is the revival of these ideas of Blanqui in France at the

present time. No doubt the agent-provocateurs will be active among the students

to try and provoke a new barricade movement which could be forcibly repressed

by the police. Far from acting as a fuse, this time it could have the opposite

effect among the workers, and help the Communist Party to regain some of its

lost influence by a renewed attack on “irresponsibles”.

Not versed in

the theory of Marxism, with the discrediting of the Communist Party in advanced

student circles, it could be expected that in this milieu all sorts of weird

and fanciful theories should find an echo. But what is tragic in the situation

in France

is that some alleged Marxists should have so distorted the rich heritage of the

ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky that they should take the line of

least resistance and swim with this mudded current of ideas. In the last few

years in France,

big gains amongst the students have been made. However, it is a thousand times

necessary to hold high the banner of Marxism. Marxist ideas since the time of

Marx himself have a thread of continuity. Though the situation has changed in

fundamental respects, the basic ideas of Marxism still remain the guide to

action which they were intended to be. To replace them with the confused ideas

of Guevarism and Castroism is to miseducate the youth and to build a further

obstacle in the path of the workers. To abandon the ideas of Marxism like the

Maoists for hare-brained anarchist schemes of armed uprisings and bloody

encounters with the police in isolation from the movement of the mass of the

workers, is the very opposite of what Marx and his continuers have taught on

the theory of insurrection.

During the

course of the May events, by and large, the organisations claiming to represent

the ideas of Trotskyism put forward many correct ideas such as the linking of

the committees of action in the factories locally and nationally. They

correctly criticised the role of the Communist Party and the other mass

workers’ organisations in these events.

At the same

time they also made many errors by imagining that the first beginnings of the

Revolution in and of themselves could replace the need for a mass Marxist

organisation. They failed to understand that for the tiny Marxist wing of the

working class, comprising a few thousand at most, the subjective factor of the

Communist Party, of the P.S.U. and S.F.I.O. are for them objective factors

standing as gigantic obstacles in the way of the Socialist Revolution. One

cannot wish away the mass organisation, but only by correct policies and

methods in first winning the militants referred to above, and then capturing

through them the masses, can the way be cleared for the victory of the

Socialist Revolution in France.

To try and substitute for real events and actions on the part of the working

class activity by students separate and apart from the workers is a new theory

of revolutionary romanticism but has nothing in common with the method and

ideas of Marxism.

From the view

point of Marxists once De Gaulle had dropped his Bonapartist referendum and

turned to elections instead and the Communist Party had gladly taken this as a

means of diverting the masses away from extra-parliamentary struggle, then

unfortunately, given the weakness of the Marxist tendency, it was necessary to

change tactics. Unfortunately, this was imposed on the Left forces by their own

weakness. They could not offer a mass alternative of action to put in place

of the elections.

It was

correct to brand the policy of the Communist Party leadership as a base and

even sinister compromise with Gaullism in refusing to take power. But at the

same time to label the elections as treason and to divert the students, already

confused by petit-bourgeois ideas of anarchism and semi-anarchism, was to play

into the hands of the leadership of the Communist Party and to further confuse

and disorient the leading militant layers amongst the students. It was

necessary to explain to them: while denouncing the “treason” of the Communist

Party at the same time a class programme should have been put forward for a

Communist-Socialist Government with a worked-out programme of demands also for

the middle classes and peasants. Instead of parading with meaningless

denunciations of the elections, calling on the people not to vote, they should

have taken the declaration of Waldeck Rochet referred to above and

systematically campaigned among the militants, the factory workers, the serious

elements amongst the students, the Trade Unions, and workers organisations. In

this way they could have pointed to the failure of the Communist Party to fight

the election on this basis. They could have systematically ridiculed the

Communist Party leadership as the new proponent of “Law and Order” with

quotations from Marx’s 18th Brumaire.

Among

Communist Party militants also Lenin’s merciless criticism of Noske and

Scheidemann who also stood as proponents of “law and order” in the German

Revolution of 1918, could have been used to try and show them the real role of

their leadership.

The slogan of

“boycott the elections”, in so far as it had any affect at all, could only have

been negative: on the one hand reinforcing the prejudices of the students and

on the other hand alienating the workers. The results of the elections laid

bare the folly of the call for boycott: 80 percent of the electorate voted,

including the overwhelming majority of the workers.

These

comrades are sincere and of the best quality, especially the rank and file. At

the moment they are under the heavy boot of Gaullist repression with the

gleeful and silent complicity of the Communist Party. It is clear that every

sincere revolutionary throughout the world will render aid, sympathy and

support to these courageous comrades. But we would be doing a great injustice

to their sacrifice and to the sacrifice of the advanced layers amongst the

students and young workers if we did not at the same time criticise what we

conceive to be incorrect policies. The first and most imperative task of

Marxists in France, and of those in the rest of the world, who wish to give aid

to the French Revolution, is to understand the processes of the revolution

itself, to understand the problems of the revolution, to have a due sense of

proportion, to understand the forces at one’s disposal and the gap between

these forces and the great historic tasks which loom ahead. It is tragic not to

understand that, for the reasons analysed above, the Revolution in France will

pass through many phases of reaction and advance, of despair and movement

forward on the part of the working class.

|

| Ted Grant |

One thing is

clear: the Revolution in France

can never be accomplished until the mass of the working class understands the

role of the leadership of the Communist Party. In the inevitable new upsurge

which lies ahead in the coming years it is from the militants of the Communist

Party, of the C.G.T., C.F.D.T. and P.S.U. that a revolutionary party will be

constructed. Events themselves will undoubtedly result in a split in the

Communist Party from top to bottom, but to aid and fertilise this process is

the real task of the Marxists. The process can only be harmed by adventures and

attempts at short cuts. The whole essence of the Revolution lies in the change

in consciousness in the masses. This can only be assisted if the Marxists adopt

correct policies and tactics. Lenin and Trotsky made many mistakes but they

never made elementary blunders and they checked and rechecked their ideas and

theories on the basis of the masses. Never would they have allowed themselves

to abandon any of the fundamental ideas of Marxism. The mass revolutionary

party in France

will be created by the coming together of the elements mentioned above. The

British Marxists hope to assist in this process by producing this material. We

are convinced of the invincibility of the Socialist Revolution which has begun

in France and of its

widespread repercussions East and West, not least in Great Britain. We are also

convinced, as the history of the last fifty years has tragically demonstrated,

that only the well tested ideas of Marxism and no new-fangled “theories” (in

reality moth-eaten resuscitations of the past), can serve to create the

necessary instrument for the victory of the workers.

17th

August, 1968.

Read more by Ted Grant at www.tedgrant.org