This morning we heard the tragic news of the death of comrade Ted Grant, just a few days after his 93rd birthday. The news was a great shock to all of us. Despite his age and the obvious deterioration of his condition in the last period, we had grown used to the idea that he would always be there, a permanent fixture amidst all the turbulence and change.

Ted himself seemed to be convinced that he would never grow old, never mind die. That explains his well-known aversion to birthdays. When I went to visit him on his birthday, he was completely indifferent to the decorations on the door of his room. He wanted only to hear of politics, the revolutionary struggle and the work of the International Marxist Tendency. He was a man who only lived for the cause of the working class and the socialist revolution. That was true right to the end.

Although he lived most of his life in Britain, Ted Grant was South African by birth, and never quite lost his native accent. He was born in 1913 in Germiston, just outside Johannesburg. He told me that he was first aroused to political life by the treatment of the black workers. From a very early age, he was interested in Marxism. He told me he had started to read Capital when he was 14. It was the beginning of a lifelong passion for Marxist theory.

Inspired by the Russian Revolution, he was won over to Trotskyism by Ralph Lee, a member of the South African Communist Party, expelled for supporting the Left Opposition. Because of the very difficult conditions in South Africa, the comrades decided to move to Britain, where they saw greater prospects for building the movement. In 1934, Ted moved to London, where he lived ever since.

Shortly before the War, he spearheaded the formation of the Workers International League (WIL), which is the original group from which we are descended. Later, the WIL fused with other Trotskyists to form the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). Ted was always very proud of the work done by the WIL and the RCP. The publications of this period, including the Socialist Appeal, contain a wealth of valuable political material that is well worth reading today. Some of it can be found in The Unbroken Thread, an important anthology of Ted’s writings, and we aim to re-issue most of it on our web page Tedgrant.org.

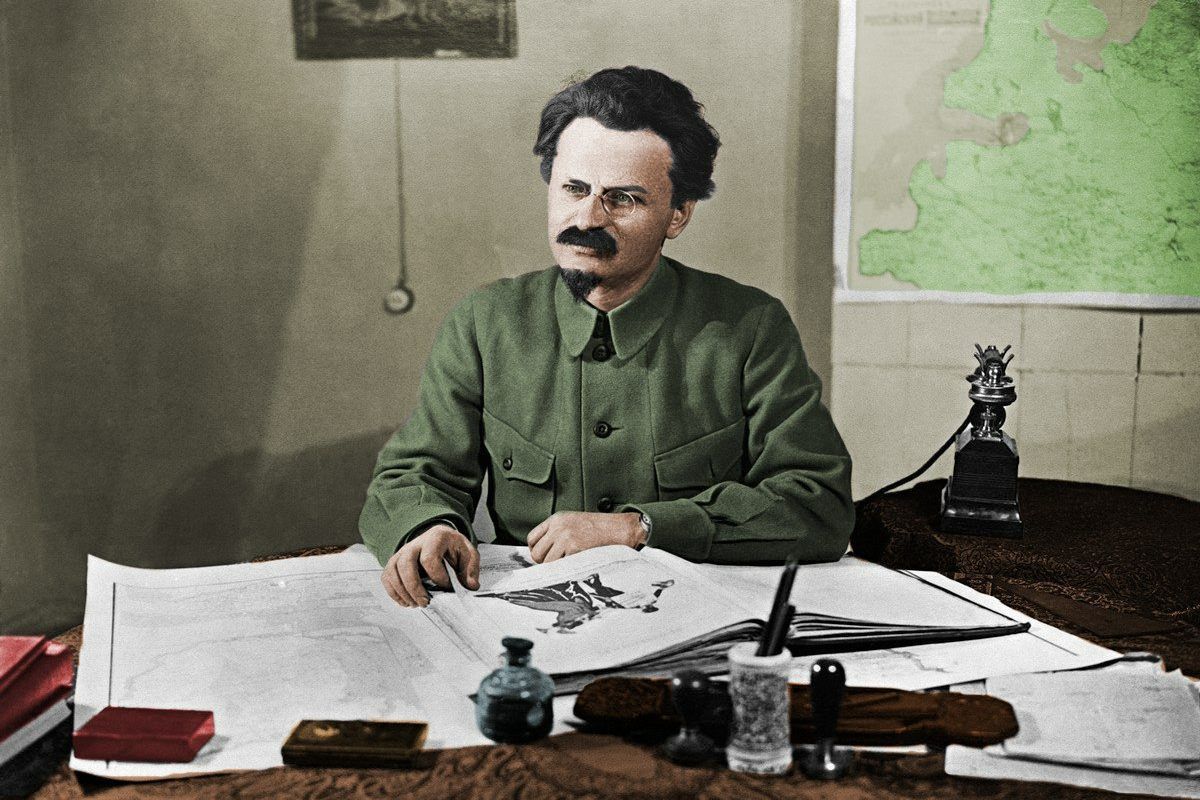

The murder of Trotsky

The assassination of Trotsky in August 1940 dealt a devastating blow to the young and untested forces of the Fourth International. Unfortunately, the leaders of the Fourth were not up to the level of the tasks posed by history. Deprived of Trotsky’s leadership they made a series of fundamental mistakes. Only the leadership of the RCP in Britain was able to readjust to the new situation on a world scale after 1945.

This was the result of the theoretical capabilities of Ted Grant. His writings on economics, war, the colonial revolution, and particularly Stalinism, were, and still remain, classics of modern Marxism. It was on this basis that the forces of genuine Marxism were able to regroup and build under difficult conditions.

Ted always stressed the vital role of Marxist theory, for which he had a real passion. At every important stage in the development of events he would always go back to the classics, the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky, which he knew like the back of his hand. This was the basis of all his work and the secret of his success. It explains how he was able to keep together a small group of loyal comrades in the dark and difficult years of capitalist upswing that followed the Second World War, when the forces of genuine Marxism were reduced to a tiny handful, and our tendency consisted only of isolated pockets of supporters in Liverpool, London and South Wales.

It takes a particular kind of courage to keep going in a period of general backsliding and apostasy, such as the 1950s. But Ted was always utterly irrepressible. He had a complete confidence in the future of socialism and he conveyed this to everyone who came into contact with him. He also had a marvellous sense of humour, which was infectious. With Ted around, one did not feel entitled to be pessimistic or downcast. But in the last analysis, this unconquerable spirit of optimism always rested on Marxist theory.

With the help of such comrades as Jimmy and Arthur Deane, Pat Wall and other stalwarts, Ted managed not only to keep the tendency alive, but to strengthen it. He worked out the perspective that the forces of Marxism could only be built through systematic and patient work in the mass organizations of the working class. In Britain that meant the trade unions and the Labour Party – particularly the Young Socialists.

The Militant Tendency

I first met Ted in 1960, when he came to speak to the Swansea Young Socialists, of which I was a member. I was bowled over by his grasp of Marxism, the clear way he had of expressing even the most complicated ideas in simple language. We were gradually developing a base in the YS, not just in Liverpool, but in London, Tyneside, Swansea and Brighton.

In 1964, we decided to launch a new paper called Militant. We held our first meeting in a small room in a pub in Brighton. At the time I doubt if many people even noticed. But within fifteen years the Militant Tendency was an important element in British politics and was a household name. Somebody once described it as the fourth political party in Britain. Although we were not actually a party as such, there is some truth in this assertion. At its height, Militant had around 8,000 members, a big centre in London, three members of parliament and more full-timers than the Labour Party.

Thanks to the work of the Militant, the ideas of Marxism gained widespread support in the Labour Party and the unions. This was a concrete expression of the correctness of the ideas, tactics and methods worked out by Ted Grant. The right wing and its capitalist backers, were beside themselves. They could afford to laugh at the antics of the sectarian groups on the fringes of the labour movement, but this was different.

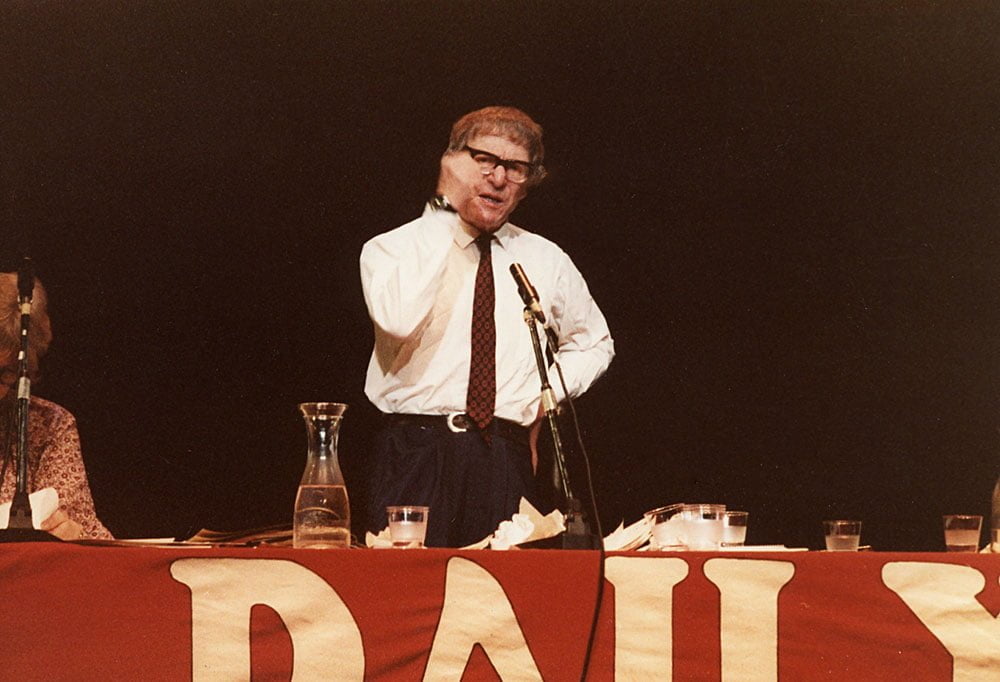

Inevitably, the right wing launched a ferocious witch-hunt against the Militant, culminating in a wave of expulsions. In 1983, Ted was expelled from the Labour party, along with the other members of the Editorial Board. In a defiant speech to the Labour Conference, Ted said: “We’ll we back!” He told them that there is no way Marxism can be separated from the labour movement.

That was undoubtedly the only correct position to take. Ted always used to say: “outside the Labour Movement there is nothing!” The truth of these words has been shown a thousand times. Yet there are some people who never learn. Unfortunately, a section of the Militant leadership allowed our successes to go to their head. They decided to follow the well-trodden path of all the sects and break from the Labour Party. In order to do this, they first had to expel Ted and those of us who supported him. Those who were responsible for this criminal act of folly justified it by arguing that it was a “short cut” to the masses, to which Ted, with his customary sense of humour, replied: “Yes, a short cut over a cliff”. And so it was.

I remember those meetings of a small group of comrades in my flat in Bermondsey. I remember as if it were yesterday Ted’s remarkable good humour. After we were expelled from the Militant, he joked: “Well, that is the best split I’ve ever been through!” But in truth, we found ourselves (in Britain at least) in quite a difficult position. After the fall of the Soviet Union, there was a general mood of pessimism on the left. Marxism was under attack from all sides. What was our duty in such circumstances?

Following the example of Ted, we decided that our first duty was to defend the fundamental ideas of the movement. We published Reason in Revolt (which has been a tremendous success internationally), then Ted’s book Russia – from Revolution to Counterrevolution. Ted and I collaborated on many more books, pamphlets and articles, which I regard as the culminating point of a political collaboration and close friendship that has lasted 46 years – until this morning.

Memories of Ted

The readers of Socialist Appeal and Marxist.com know Ted Grant as a Marxist theoretician of stature. But what of Ted Grant the man? He was a very humane person – not at all like the stereotype of a sinister revolutionary. He was always approachable and would converse on all manner of subjects with anybody who happened to be handy – a bit like Socrates in the Agora at Athens, only it was more likely to be the bus stop or the fish and chip shop. His motto could well have been: “I regard nothing human as alien to me.”

I remember when I was at university in Sussex we had won over a couple of students from Healy’s organization. They were very bright kids and wanted to speak with Ted, so I fixed up a meeting. The conversation went on for a long time, and they were obviously mesmerised. Afterwards I asked them how it went and they said they were amazed at the encyclopaedic scope of his knowledge. At one point one of them asked him if he knew anything about Scandinavia, to which he replied: “Not much” and then commenced an hour-long speech on the politics, history and economic life of Norway, Sweden and Denmark.

He had a very wide range of interests and could speak about football and horseracing (he enjoyed the occasional bet) as well as literature and culture in general. His favourite authors were Jack London and Galsworthy. Of the Forsyte Saga he once remarked to me: “he [Galsworthy] showed the bourgeois as they really are, and they never forgave him”. What a wonderfully perceptive piece of literary criticism! However, he and I could never see eye to eye on James Joyce.

Ted was always very health conscious. “Marx and Lenin did not look after themselves”, he used to say, with a reproving look, as if he were scolding the founders of scientific socialism for their carelessness. He was also very particular about his diet. He would eat enormous quantities of fruit for breakfast, for example. He did not smoke and only began to take the odd glass of red wine with food in the last few years because he read somewhere that it was good for you. On the other hand, he had a voracious appetite, and more than one comrade found himself eaten out of house and home after one of Ted’s flying visits. However, he did not put on weight because of a vigorous programme of exercise carried out religiously for at least an hour every night before going to bed.

Ted was not at all self-conscious about his appearance. The exception was when he visited his elder sister Rae in Paris. Rae (who died only last year), unlike her brother, was extremely fashion conscious and would not be happy unless her brother appeared before her suitably dressed. Therefore, some weeks before leaving for Paris, Ted would pester comrades to help him to buy a new suit. It had to be a blue serge suit (he explained) because that was what Rae liked. After many years of this performance, somebody asked Rae what she thought of Ted’s new suit, to which she answered: “I wish to goodness somebody would tell him to stop buying those awful blue serge suits!”

Ted as a comrade

Ted was not the easiest man to work with. His profound grasp of Marxism, and his insistence on 100 percent correctness, made him a hard taskmaster, especially where writing was concerned. He would go over a manuscript a dozen times, red pencil in hand, crossing out, underlining and scribbling indecipherable comments in the margin, while the unfortunate author looked on aghast. This upset some people, but personally I regarded it as a useful training. After all, the important thing is the ideas, and not the personal ego of aspiring authors. Those who put the ideas first learned a lot.

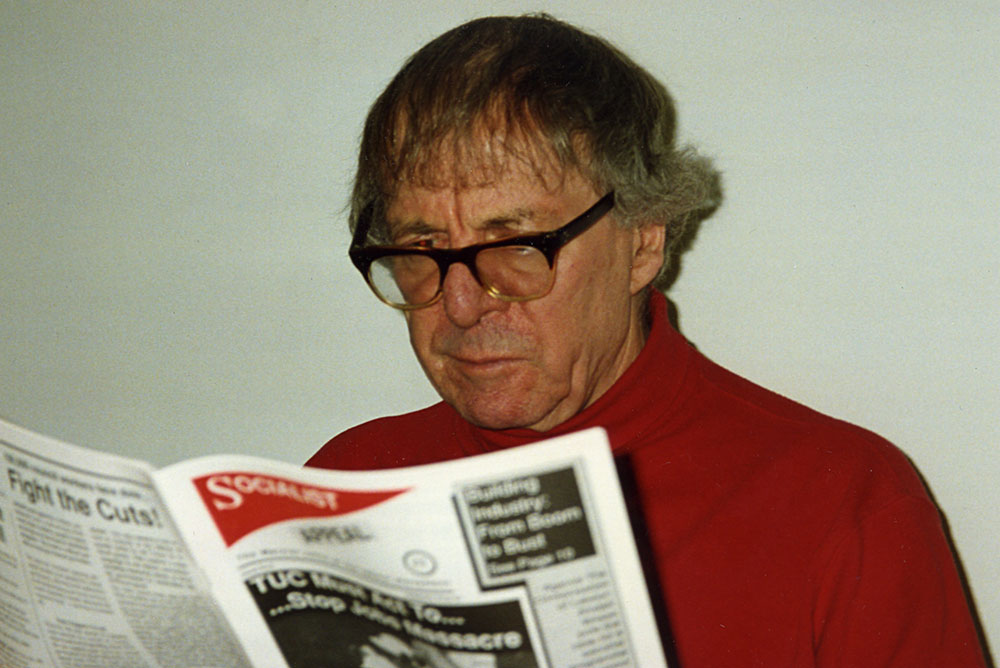

Ted had a limitless appetite for political work and discussion. But he had his own routine and would not allow himself to be deflected from it. He did not read the daily papers – he devoured every line. Every day he read The Financial Times, The Morning Star and (for reasons that I could never grasp) The Daily Express. “You must read them all, from the first page to the last,” he would say: “This is contemporary history”. On demonstrations he would always be there, pacing up and down the lines of marchers, with his Socialist Appeal held out boldly in front. He usually sold more than anybody else. There was something about him you could not say no to.

But where he really came into his own was public speaking. He would usually speak for an hour – sometimes more – and could always hold people’s attention. His speeches showed a thorough grasp of the subject matter, with plenty of facts (“facts, figures and arguments are what is needed” he used to say, when advising on writing or public speaking). There was none of that kind of negative, mean-spirited, spiteful element in his speeches that so often characterises the ranting of the sects. There would be no personal attacks, but he would often give vent to his sense of humour, especially when speaking of the bourgeois or right wing leaders. Sometimes he would even burst out laughing when speaking of the stupidities of these ladies and gentlemen, and this was so infectious that it would have everybody splitting their sides.

Ted was particularly interested in Marxist economics and Marxist philosophy. His pamphlet Will There be a Slump? is a little masterpiece, while The Marxist Theory of the State is one of the very few works of modern Marxism that can be said to have added to and developed the theories of Marx and Engels. In connection with his passionate interest in Marxist philosophy, he followed all the developments of modern science very closely. There was one remark that struck me as particularly profound. He said that in the human mind, “matter has finally become conscious of itself”. A more beautiful way of expressing philosophical materialism it would be difficult to imagine.

The last period

At the time of the split in Militant Ted was already a “young man” of 78. But he just carried on as before, travelling to other countries, delivering speeches of an hour and a half. He seemed determined to carry on forever. At times it seemed that he had convinced himself that he would do just this. It was a truly formidable performance. But Nature sooner or later asserts her dominance.

Ted was speaking at a meeting in London a few years ago when he suddenly stopped dead in his tracks. We later realised he had had a small stroke. He made a good recovery, but the red light was already flashing. A dedicated group of comrades helped Ted as much as was possible, but his physical condition was clearly deteriorating. This deterioration accelerated after an operation for prostate trouble. He was no longer able to carry out work as before and only rarely spoke at meetings.

In the end he needed fulltime professional care and entered a residential home in the countryside near Romford. Here he had his books and was visited by comrades who made sure he was well looked after. In this context, we particularly wish to thank comrades Steve and Sue Jones. Ted was comfortable enough, physically strong for his age, still able to walk unaided, and not in any pain, but he longed to be active again. He wanted to hear about the work of the tendency (small talk never interested him in the slightest). I told him about the successes of the IMT in Venezuela. He brightened up: “So we are doing well, then?” “Yes, Ted, we are doing very well. And it is all thanks to you.”

Although in general his concentration and memory were deteriorating, he had lucid spells when he was quite capable of participating in political discussions. I took advantage of these days to make some interviews on the history of the Movement, which we published on Marxist.com. A few weeks ago I asked him: “If you were to meet with Chavez, what would you say to him?” He answered immediately: “I would tell him to take power.”

The last time Ana and I visited him was last Sunday (his 93rd birthday). He seemed a lot slower than usual and did not talk very much, but he was still able to walk us to the front door. I spoke to him on the phone almost every day since then. Yesterday evening he phoned again and asked when I was going to visit him, I answered that I would call in on Friday morning, when I hoped to bring Manzoor Ahmed, the Marxist MP from Pakistan, to see him. He was well pleased and that was how we parted.

That meeting was destined never to take place. Ted Grant is no longer with us. The man who did so much to defend the ideas of Marxism, and who almost single-handedly saved the heritage of Trotskyism from shipwreck, has passed on. For those of us who were educated by Ted, who worked and struggled by his side to build the revolutionary movement, and who have remained loyal to him to the end, this is a bitter blow.

He was the last living representative of a remarkable generation – a generation of revolutionary giants who fought under the banner of Leon Trotsky and who saved the honour of the October Revolution and preserved its heritage to hand it on, intact and immaculate, to the new generation. Ted Grant was the most outstanding representative of that generation. He has handed the banner to us – the programme, the theory, the methods and the ideas that alone can bring victory.

Ted Grant was never a sentimental man. He would not want us to waste our time in fruitless lamentations and grieving. We will grieve the passing of a great man, comrade and friend, but we will celebrate his memory in the only way that he would applaud: by stepping up the work, by fighting for the ideas of Marxism, and by building the International Marxist Tendency. We will build a monument to the memory of comrade Grant – an imperishable monument of proletarian organization – a monument that is capable of transforming the world.

There was nobody like Ted Grant when he was alive and nobody can replace him now he is gone. But in the ranks of the International Marxist Tendency there are many experienced cadres who have absorbed his ideas and methods and are fully equipped to carry them into practice. Today nobody can doubt that the tendency created and nurtured by Ted Grant is advancing steadily and making one conquest after another on a world scale. The authority and prestige of these ideas have never been so high as they are at the present time. That is the best testimony to the correctness of Ted’s ideas and approach. It is the justification of his life’s work, for which we are all eternally indebted.

Alan Woods, London, 20th July

See also: