"I wanted to rouse these women of the submerged masses to be, not merely the argument for more fortunate people, but to be fighters on their own account despising mere platitudes and catch cries, revolting against the hideous conditions about them, and demanding for themselves and their families a full share in the benefits of civilisation and progress." (Sylvia Pankhurst)

"I wanted to rouse these women of the submerged masses to be, not merely the argument for more fortunate people, but to be fighters on their own account despising mere platitudes and catch cries, revolting against the hideous conditions about them, and demanding for themselves and their families a full share in the benefits of civilisation and progress." (Sylvia Pankhurst)

The life of Sylvia Pankhurst is rich in experience for all activists in the labour movement. The names of the Pankhurst family are synonymous with the struggle to win the vote for women, but what distinguished Sylvia Pankhurst’s approach from that of her mother Emmeline and her sister Christabel were class issues.

It resulted in the 1920s, after nearly twenty years of struggle, with Emmeline standing as Tory Parliamentary candidate and Sylvia becoming a founder member of the British Communist Party.

The seeds of such a divide were there from the early days of the suffragette organisation, the Women’s Social and Political Union. Founded in 1903 by Emmeline, Christabel Pankhurst and others, the WSPU was first conceived of as an auxiliary to the labour movement to secure equal rights for women. But during the early 1900s it developed an entirely independent existence severing its links with the organised working class.

The WSPU undoubtedly played a major role in publicising the issue of women’s suffrage through demonstrations, imprisonments and sometimes violent campaigns. But Sylvia Pankhurst, in spite of her middle-class background and relatively privileged position, found herself more and more drawn to the position of working class women.

Two years before the founding of the WSPU, women workers in the Lancashire cotton mills linked the right to suffrage to the removal of discrimination and exploitation and presented a petition of 29,000 signatures to Parliament demanding the vote. The mill owners so very considerately did not pay women workers the proper rate for the job because they didn’t want to "tempt women out of their proper place in the home looking after the children."

More and more women were becoming involved in strikes and protests over wages and unemployment. In 1904 Sylvia Pankhurst and others organised a 1,000-strong march for jobs from London’s East End to Westminster.

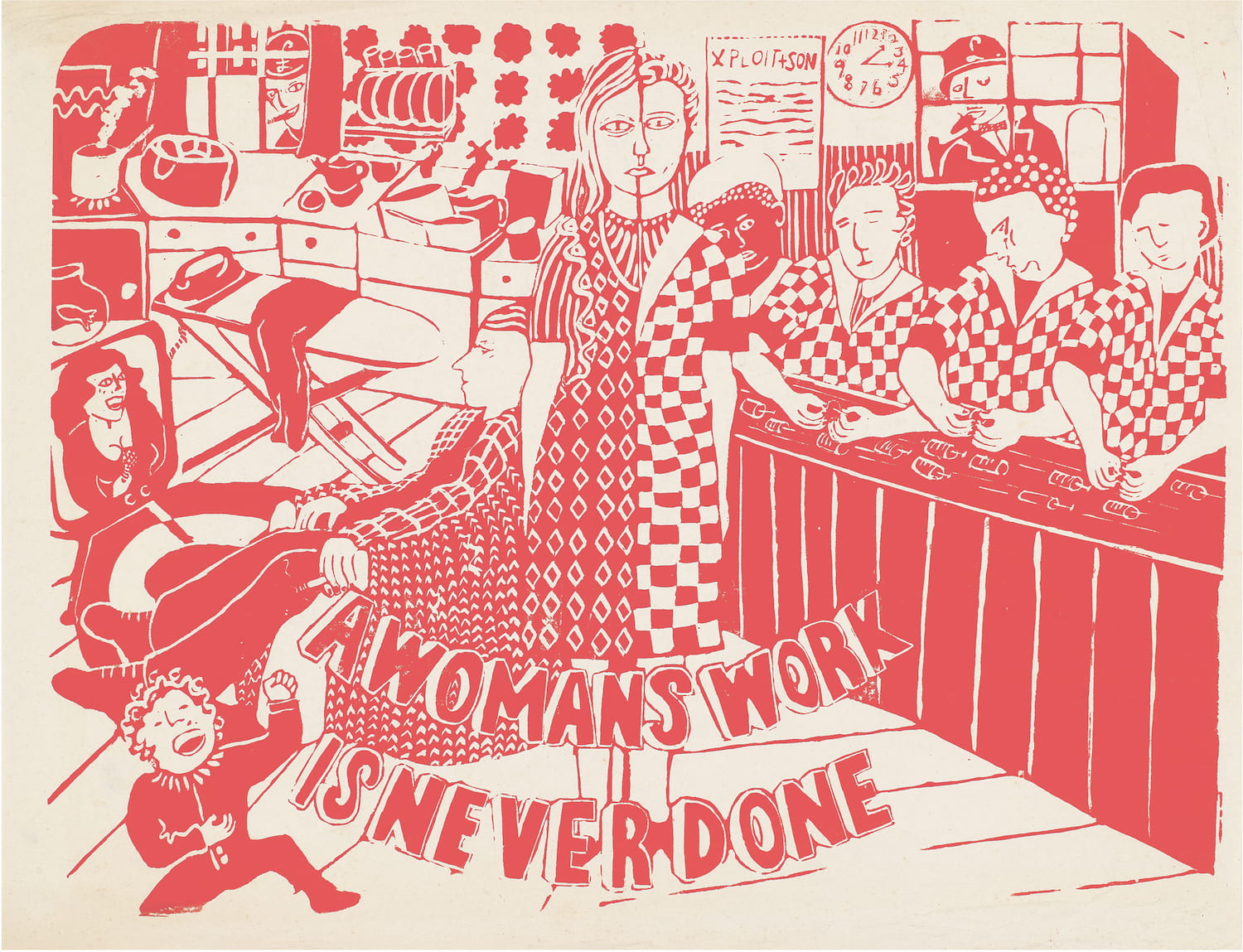

At this time Sylvia’s main desire was to paint, and perhaps it was a tour of Northern towns in 1907, painting the working class at home and at work, that brought home to her the exploitation in industry, agriculture and, through bad housing conditions, the lack of sanitation. This experience along with her activity in the East End resulted in Sylvia questioning the tactics of the WSPU, the increased militancy, stone-throwing and the hunger strikes. This was not because she was not prepared to go on hunger strike; between June 1913 and June 1914 Sylvia endured 10 hunger and thirst strikes.

Working class women

What was needed, she said, was "not more serious militancy by the few but a stronger appeal to the great masses to join in the struggle." In 1912 she began full time work for the movement, abandoning her art, and rejecting the terrorist tactics of arson called for by Christabel in favour of a broader and more confident appeal to the people, particularly women, from London’s East End. Rather than just coming to hear well-known speakers she encouraged people to address meetings themselves in the streets and markets.

She addressed a meeting of 10,000 at the Albert Hall, organised by the Labour newspaper Daily Herald, to protest at a mass lockout of Dublin workers and the imprisonment of James Larkin for organising strikes. "Every day the industrial rebels and the suffrage rebels march nearer together," commented the Daily Herald.

These links did not go unnoticed by the suffragettes around Christabel who stressed the independence of the WSPU from all men’s parties and led to the final break between the East London Federation of the WSPU and the WSPU itself in January 1914, and the formation of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). One argument used by Christabel against the East London Federation was that it had a democratic constitution and relied too heavily on working class women – she argued, in effect, that the fight for women’s votes shouldn’t apply within the WSPU itself!

This split in the WSPU reflected a general polarisation taking place in British society. Between 1911 and 1914 every key section of workers (dockers, transport workers, railway workers, engineers) were involved in strikes. Even amongst the members of the WSPU, who were imprisoned and force-fed, it was working-class women who suffered the worst conditions and treatment.

There were so many women in prison and on hunger strike that the government had to introduce in 1913 the Temporary Discharge for Health Bill (or as it became known, the "Cat and Mouse Act") whereby women were discharged until they were well enough to be re-arrested and complete their prison sentence.

Under the editorship of Sylvia, the ELFS brought out the Women’s Dreadnought. An indication of the ELFS’s activity is illustrated by the eighteen meetings in the East End of London advertised in the first issue, March 21, 1914.

Like the rest of the labour movement, however, the women’s organisations were confused when the first world war broke out five months later. Emmeline and Christabel became enthusiastic supporters of the British war effort, suspending activities and agitation for the vote until the war was over.

Sylvia, like many in the labour movement, adopted a pacifist position. But she still carried on the suffrage campaign and the fight for fair wages for women drawn into the factories to replace men sent off to war.

The first world war meant even greater hardship for working class families in the East End, and many turned to ELFS for help. They tried to help by putting in claims for poor relief, establishing a toy factory to aid employment, providing cost-price restaurants and "mother and infant centres" to ameliorate some distress.

The war and the Russian Revolution deepened Sylvia’s understanding. By July 1917 the Women’s Dreadnought had become the Workers’ Dreadnought, the organ of the Workers’ Socialist Federation, and Sylvia became a firm supporter of the Bolshevik Revolution earning herself the nickname "Little Miss Russia".

She called the 1918 extension of the vote to some women over 30 as "fancy franchise" because the vote was limited to property-owners, university graduates etc. Although this was true, the vote for some women nevertheless showed the fear of the ruling class at the increased militancy of the women munitions workers and the fear that the women’s suffrage movement would link up with these and other workers towards the overthrow of capitalism.

After years of fighting for the right to vote in Parliamentary elections, Sylvia Pankhurst by now considered Parliament as an institution manipulated by the capitalist class, which should be abolished and that no communists should participate in it. Lenin strongly argued against this viewpoint in his pamphlet "Left-Wing" Communism – an Infantile Disorder.

War and Revolution

The question of Parliament and the issue of affiliation to the Labour Party were stumbling blocks in the bringing together of various communist groupings in Britain. Sylvia argued that British Communism "must keep its doctrine pure… its mission is to lead the way by the direct road to the revolution."

Whilst Lenin recognised the instinctive hatred of the WSF for Parliamentary opportunists, he argued that boycott was wrong and that they should participate in all the struggles of the working class, winning their confidence and guiding the movement in the direction of socialist change. This – he stated – far from creating illusions in the reformist policies of the Labour Parliamentarians, was in fact the only way to give a lead.

Although a founder member of the British Communist Party, Sylvia later became disillusioned and was horrified by the purges of Stalin and the trumped-up charges against leading Bolsheviks during the 1930’s Moscow Trials.

Her last 20 or so years were taken up with the fight against Fascism and the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini. The New Times and Ethiopia News which she established in May 1936 did not limit its coverage to Ethiopia but argued support for the republicans in Spain against Franco. She died, aged 78 in 1960 in Ethiopia.

The legacy of Sylvia Pankhurst lives on. Her own experience showed that militancy and self-sacrifice of women at home or at work must be linked to the struggle of the whole of the working class, and that the vote could only be a first step to opening the door to socialism.