“Do not let composers who have written works unintelligible to the people think that, while the people may not understand this music now, they will do so when they have become more mature. The people do not need music which they cannot understand.”

These were the words of Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s chief culture ideologue, at the 1948 Congress of Soviet Composers.

Such ignorant statements perfectly capture the essence of the Stalinist policy of ‘Socialist Realism’, which accepted nothing less than a glorification of the bureaucratised Soviet regime. Any art which was deemed non-compliant by the authorities was denounced and suppressed.

After ripping through the field of literature in 1946 – when Zhdanov condemned Mikhail Zoschenko for his searing satirical talent, and poet Anna Akhmatova, calling her a “half harlot, half nun” – the time had come for some cultural ‘education’ on the musical front.

Campaign of hate

In the course of this artistic counter-revolution, the music of composers like Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Khachaturian, Myaskovsky, and Shebalin was condemned and their works censored and struck from the performance programmes across the country.

The spiritual impact of their works was compared by one of the speakers to that of a dushegubka – the Russian nickname for the gas chamber vans used by the Nazis across Eastern Europe only a few years prior.

This barbarian act of imposing crude bureaucratic demands on music was yet another one on the long list of crimes of Stalinism.

Such an approach to art and culture is completely alien to the spirit of genuine Marxism, and is the opposite of the original policy of the Bolsheviks under Lenin and Trotsky: encouraging the flourishing of ideas and cultural innovation free from party diktats.

Under the guise of ‘anti-formalism’, however, Stalin’s apparatchiks tried to impose the most crude forms upon music, in order to control it.

This cultural crime would claim some very real victims as well. Both Prokofiev and Shebalin would suffer their first strokes not soon after, seriously impacting their health and livelihoods.

Shebalin’s stroke was so severe, that he tragically composed his final Symphony no.5, unable to use any other language but that of music. While ill on his deathbed in 1950 Myaskovsky was tortured by the trauma of Stalin’s campaign of hate, according to Shostakovich. Tragically, he was even doubting himself: could it be that we are indeed the enemies of the people?

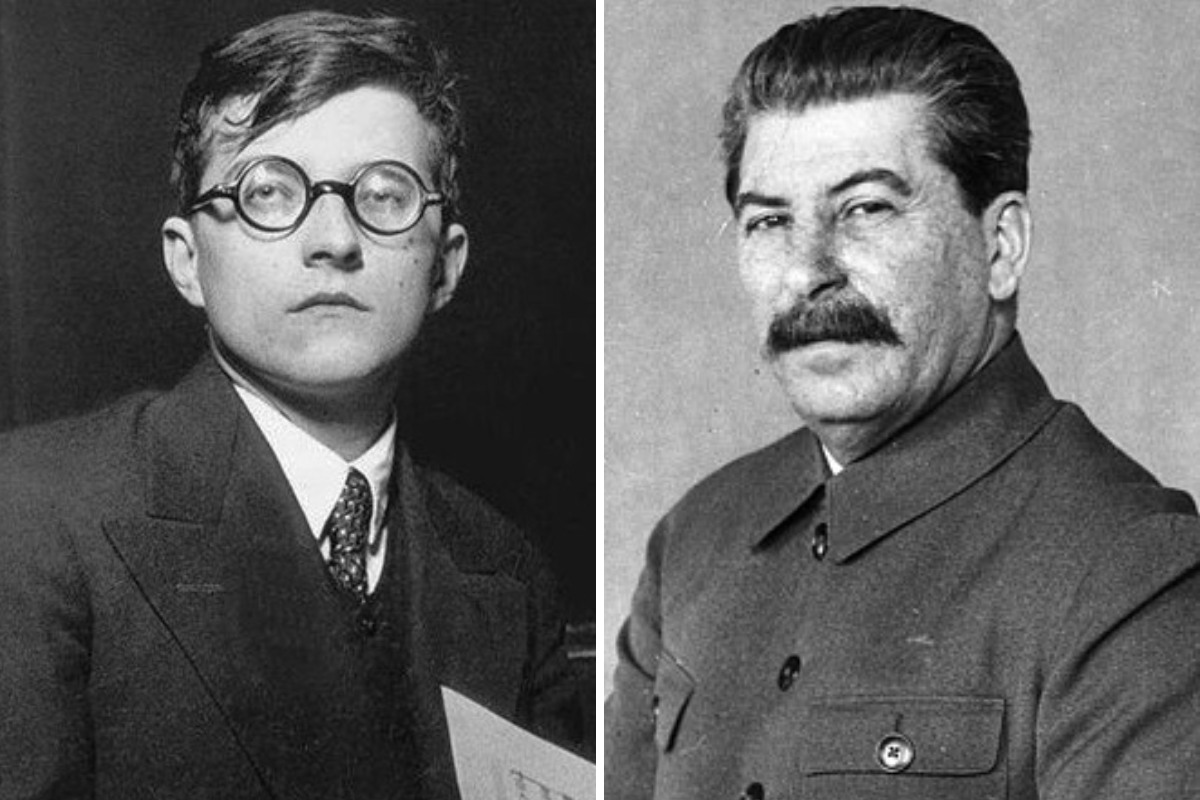

Shostakovich’s scathing satire

Dmitri Shostakovich was on the brink of suicide, suffering poverty and isolation like all the others. Thankfully he didn’t end up following through on his plan, and instead forged perhaps the single most scathing piece of satire known to classical music.

Anti-formalist Rayok, subtitled As an aid to students: the struggle of the realistic and formalistic directions in music, is a cantata depicting the speeches of comrades Primin, Twokin, and Threekin, who clearly represent Stalin, Zhdanov, and their loyal nobody Shepilov.

A side note on the names of the characters: the grading system in Russian schools is based on numbers, and not letters, with grades 1, 2, and 3 being the lowest, reserved for failed students. Make of that what you will.

What ensues is a riveting show of the composers’ defiance and utter ridicule of those narrow-minded bureaucrats. Primin-Stalin enters to an applause of the choir with a pipe and fake moustache:

“Comrades! Realistic music is written by people’s composers, while formalistic music is written by anti-people’s composers.” (…)

“Let us thank our father, our beloved Great Primin for his enriching and enlightening coverage of important matters of the music trade. Thank you, thank you for the historic speech!”

This is set to the melody of the Georgian folk song Suliko – Stalin’s favourite – which is ridiculously extended and strained to fit the words of the “Dear Leader”.

Twokin or “Musicologist No. 2” takes the floor to the music of another heavily promoted ‘people’s’ classic Kamarinskaya.

What follows is a series of direct quotes from Zhdanov’s speech: on how everything must be “beautiful” to reflect the “new Soviet life” – and not resemble the “dentist’s bore-drill” or the aforementioned Nazi gas chambers.

Shepilov, who had a reputation for being one of the most cultured men of the apparatus, comically misaccentuated Rimsky-Korsakov’s name when ordering the “formalist” composers to make their music more like the classics: Glinka, Tchaikovsky, and Rimsky-KorSAkov.

Shostakovich immortalises this farce, as Threekin’s speech devolves into another joke on the folk classic Kalinka, and a direct call for sending composers and conductors to gulags.

This work was “written for the drawer” and premiered 14 years after Shostakovich’s death. Some of his friends advised him to burn every trace of it, as others were shot for far less.

It is rather telling then, that Shostakovich didn’t joke at the expense of The Internationale, Varshavianka, or other communist songs – but rather the “national” folk music pushed so intently by the Stalinists.

The reason for this is clear, Shostakovich remained a Bolshevik through and through, and was criticising Stalinism, not communism and the genuine legacy of the October Revolution.

The performance recording available on YouTube – with bass Sergei Leiferkus performing all vocal parts masterfully with Moscow Virtuosos under Vladimir Spivakov – adds yet another layer of irony. None other than Boris Yeltsin himself is present in the audience: the drunkard epigone who oversaw the complete sell-off of the Soviet Union after its tragic collapse.

The musicians take a shot at this ‘new’ bureaucracy, humorously noting that only the content of their speeches had changed, but their hypocrisy remains the same. Yeltsin seems entirely oblivious to the fact.

To this day, Shostakovich’s music, and his revolutionary spirit, resonates clearly with all those with ears to hear – but remains a closed book for the narrow-minded philistines of the so-called ‘elites’.

Peter Kwasiborski will be speaking on ‘Shostakovich: The musical voice of the Russian Revolution’ at Revolution Festival 2025 (14-16 November).