Nick Hallsworth – a Marxist student delegate from Leeds University – reports on NUS Conference 2017, where a well-prepared and organised right wing outmanoeuvred the Left. Nick draws out the lessons to be learnt and explains where the student Left needs to go from here.

Nick Hallsworth – a Marxist student delegate from Leeds University – reports on NUS Conference 2017, where a well-prepared and organised right wing outmanoeuvred the Left. Nick draws out the lessons to be learnt and explains where the student Left needs to go from here.

The National Union of Students’ 2017 conference, held from 3-5 May in Brighton, was deeply divided. Since the election in 2016 of Malia Bouattia ‒ a left-winger who promised to take the NUS into political struggle against the government ‒ the Right has been preparing a coordinated campaign to re-assert their grip in the union.

The struggle between those students who want a politicised, fighting union and those who would prefer the NUS to be a bureaucratic training-ground for career politicians, characterised the intense debates that ran throughout the conference. It is clear that the call for an apolitical NUS is in fact anything but. It is the slogan of a bureaucratic arm of student movement that seeks to hamstring its ability to fight against capitalism.

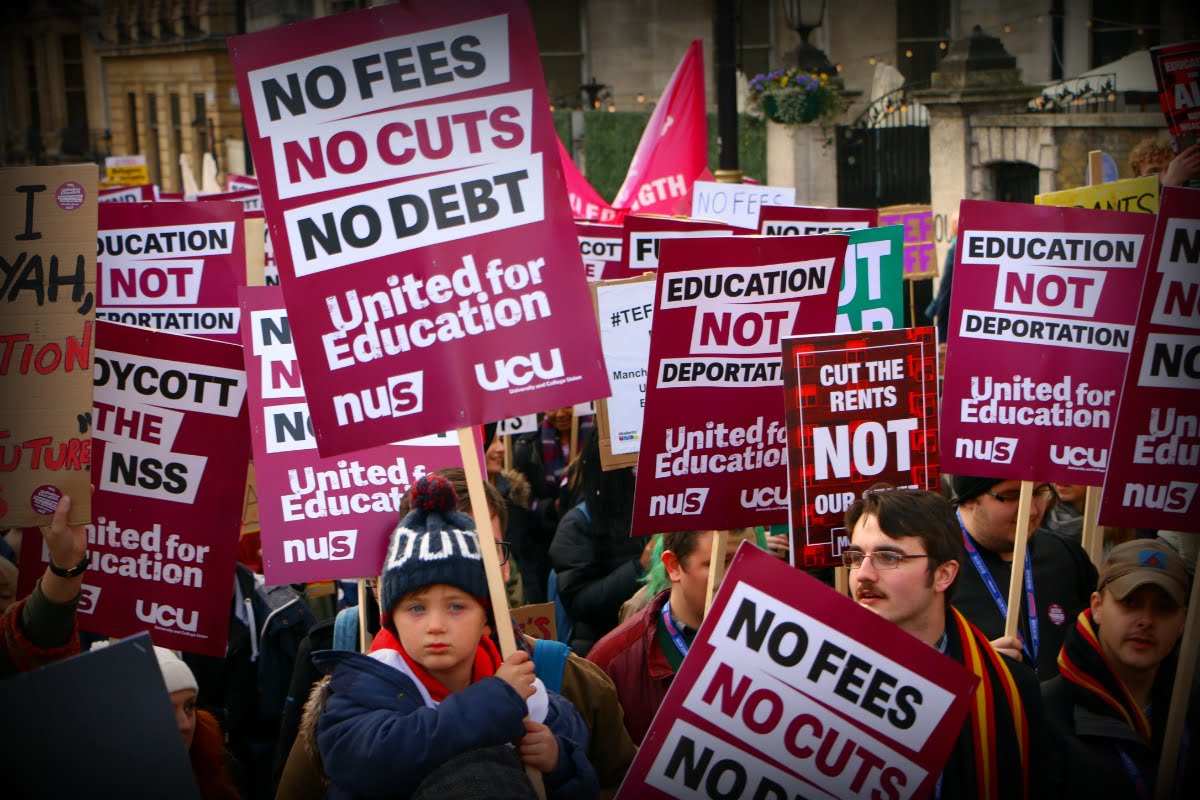

After already tripling fees in 2010, the government is now, through the Teaching Excellence Framework, attempting to further marketise education by allowing some universities to charge higher fees based on performance standards, thereby pricing out more students and extending the inequalities between institutions.

At the same time, the Tories have removed grants, increased student debt and enabled the exploitation of students through extortionate landlords. These cuts have disproportionately affected women, disabled, black and minority ethnic students; have contributed to a national mental health crisis; and have ramped up class division within education. Furthermore, the government has used racist policies such as the Prevent initiative to crack down on protest. Medical, nursing and social care students have been especially attacked, with bursaries removed and fees increased.

Despite the downturn in student activism since 2010, the election of Bouattia showed students were desperate for a politicised union, having last year voted through a boycott to the National Student Survey (part of the TEF) as well as organising a national demonstration. She promised to work with trade unions, to fight for free education, and defend the rights of minorities from racist policies. The left-wing leadership, however, faced a concerted attack by the right-wing press and the Blairites in the NUS. They sought to use any means possible to discredit Bouattia, including personal attacks and dog-whistle racism.

Former Vice-President for Further Education Shakira Martin ousted Bouattia in the presidential elections, heading up a bloc of “moderates” who managed to win all the top leadership positions, as well as forcing through a “democratic” restructuring designed to reduce the ability of the Left to organise within the union.

Bureaucracy strengthened

Conference approved several measures to strengthen the grip of the hacks and bureaucrats, including a complicated “least-worst” voting system that benefits less contentious candidates and incentivises the deletion of political content from officers’ programmes.

They also removed the ‘block of 15’ elected positions from the National Executive committee which exists to hold full-time officers to account, replaced by an online accountability system in which 10% of SUs can trigger a vote of no confidence in an officer (allowing a minority to unseat elected officers they don’t like, under pressure from public media attacks). In principle, we are in favour of the ability to recall representatives but the intention of this policy was clearly to undermine politicised candidates.

Finally, the Right introduced a post conference online ballot, as well as more online voting; taking focus away from discussion and debate at conference by democratically elected delegates. The plan also included commitments to reduce the role of the national structure in favour of regional decision-making, again negatively affecting the ability of the NUS to engage in national political struggle on behalf of students.

This motion was forced through in a shocking display of factional bureaucratic wrangling. The Right successfully managed to block the many amendments submitted from even being discussed and flooded the debate with procedural motions and votes of no confidence in the chair. This demonstrated the dishonesty of their arguments, which pledged to increase democratic involvement while blocking democratic debate on the biggest overhaul in the NUS since 1922.

Lessons to be learnt

The Left must take some responsibility for their defeats at this conference, however. They were unprepared for this coordinated attack, which won on the strength of campaigning in delegate elections throughout the year. Left students must take note of the defeats at this year’s conference and draw the necessary lessons: the need to organise, educate, and agitate from the bottom up, building a strong and coordinated grassroots movement in all campuses and colleges, on the basis of a bold and radical programme.

The Right posed themselves as the candidates of unity, realism and modernisation, spouting empty platitudes about representing the “real issues facing average students” against a “divisive hard left”, obsessed with petty factionalism and fringe radicalism. A wave of disaffiliation campaigns in Student Unions (led by a contingent of the reactionary Right) has promoted the idea that the NUS is broken, irrelevant and in need of modernisation, which suited the Blairites nicely, promoting themselves as the ideal candidates to fix it.

It was the failure of the Left leadership to take bold action that ensured the student base didn’t move with them. The NSS boycott, which attempted to disrupt the TEF, constituted an indirect, limited form of resistance. A national demonstration in collaboration with the UCU also felt perfunctory. The leadership were not putting forward a positive programme as to how they might secure their radical ideas and failed to lean on the power of the student movement itself, instead mirroring the bureaucratic, backroom coordination of the Right.

This same problem was reflected at conference. The National Campaign Against Fees and Cuts, for instance ‒ while making many correct political arguments ‒ limited themselves to arguing for boycotts and taxing the rich. The idea that an NSS boycott will be leverage enough to somehow convince the Tories to drop their vicious policies, or that the rich will consent to higher taxation without moving abroad or exploiting tax loopholes, is idealistic. Something much more radical is needed.

Pressures building

The new right-wing leadership of the NUS will come up against insurmountable pressures as their desire to be “non-political” and compromise with the establishment will quickly be seen as unable to deliver for the mass of students facing cuts and rising costs. New movements from below will develop, despite the best efforts of the NUS leadership to hold them back. The task will be to give this growing tide of anger a focus. These careerists will be seen as having nothing to offer by students looking for answers to real-life problems.

In reality, the problems students face are rooted in the crisis-ridden capitalist system. The Left in the student movement must campaign on the need to overturn capitalism ‒ not tinker around the edges. This can only be achieved by transforming the NUS into a body capable of fighting for students and joining the wider labour movement in the struggle for socialism.