The pandemic has triggered the worst crisis in the history of capitalism. The ruling class is scrambling to save their system, breaking all the rules that have governed their policy for the past 80 years. The future is socialism or barbarism.

Economic data always lags behind events, and the last official figures for the economy would be for the last quarter of 2019, with the next batch due out in April. However, it is clear that the situation has completely changed in the past month and a half.

Various institutions are now attempting to project the scale of the crisis but their models are built for the past, and would struggle to come to terms with the new unpredictable situation. Still, there is no reason to doubt the general thrust of the figures.

Morgan Stanley estimates the US economy will contract 30 percent on an annualised basis between April and June this year, after contracting 2.4 percent January to March. This would mean an unemployment rate of 12.8 percent this spring – the highest since records began in 1948.

Already, millions of people have lost their jobs. 3.28 million applied for unemployment benefits in the US last week – the highest on record. In Britain, there were ½ million new claimants to Universal Credit in one week.

The Institute of International Finance now predicts a fall of 1.5 percent in World GDP, with the US down 2.8 percent, the Euro area down 4.7 percent and China growing by a mere 2.8 percent. What they term “emerging markets”, which encompasses much of the former colonial world, they predict will grow by 1.1 percent, but that is driven by predicted growth, albeit at a much reduced rate, in India and China.

“Much of the uncertainty around our forecasts revolves around H2, however. We pencil in a return to growth in H2 [second half of 2020], assuming abating quarantines and recovering consumer and business confidence. Whether these assumptions are justified, remains to be seen and the resulting uncertainty pervades all our forecasts.”

Whilst they have some idea of what is happening right now, they have little idea of what is going to happen in a month or two, never mind the autumn. They are predicting a drop in GDP as bad as 2009, assuming things will return some semblance of normality in the second half of this year. This will depend on the ability of states to contain the pandemic, ease restrictions and imbue consumers and businesses with some confidence in the future. Not a small task.

The confidence of business is collapsing. Eurozone PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index, based on surveys of businesses) fell to 31.4 from 51.6, the lowest figure on records (which began in July 1998). Any figure below 50 signals a contraction. The PMI for the US fell to 40.5, which is not quite as low as in 2009, but close. According to the chief business economist at IHS Markit which produced the figures, the data would indicate an 8 percent fall in eurozone GDP and a 5 percent fall in the US, and he added that it is “unlikely that the index has hit rock bottom yet”.

France’s finance minister on Tuesday said the crisis was “comparable only to the great recession of 1929” and noted that French industry was operating at only 25 percent of its normal level. The German economic minister said that the crisis is testing “the functionality of the market economy” and that “whole markets are completely breaking down”.

Figures for China are harder to come by, but according to a Financial Times index, the Chinese economy is operating at 75 percent of its 2019 level. It’s down 35 percent on its level on 1 January. This would mean a devastating blow to the Chinese economy.

The ex-colonial countries are being hit hard. “Emerging markets”, as economists like to call them, have lost $83bn in investment. Several currencies are in freefall: the Mexican peso, the South African rand and the Brazilian real have all fallen by around 20 percent and the Turkish Lira and the Indonesian rupiah by around 10 percent. This is on top of previous falls over the past couple of years, which combined means these currencies have lost somewhere between one and two thirds of their value. With their massive reliance of dollar-denominated loans, these countries are in a very difficult situation.

Desperate times calls for desperate measures

The ruling class is running scared, which can be seen in the record speed at which measures are being announced. This time in the US, it took four weeks to put together a rescue package whereas it took over four months in 2008-2009. The package that they came up with is also twice as large ($2tn compared to $1tn 11 years ago).

The ruling class is running scared, which can be seen in the record speed at which measures are being announced. This time in the US, it took four weeks to put together a rescue package whereas it took over four months in 2008-2009. The package that they came up with is also twice as large ($2tn compared to $1tn 11 years ago).

Combined the USA, the ECB, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, UK, Canada and Australia have announced $2.2tn in central bank measures and $4.3tn in central government measures. This is the equivalent of 17 percent of the combined GDP of these countries, or 7.3 percent of world GDP. The Chinese central government has announced $587bn worth of measures, which is around 5 percent of its GDP.

It’s not just the size of the packages that are being prepared but the entire rule book for the role of the state in the economy is being ripped up. Mario Draghi, the former head of the European Central Bank argued in the Financial Times:

“It is already clear that the answer must involve a significant increase in public debt. The loss of income incurred by the private sector — and any debt raised to fill the gap — must eventually be absorbed, wholly or in part, on to government balance sheets. Much higher public debt levels will become a permanent feature of our economies and will be accompanied by private debt cancellation.”

In a nutshell: the government must step in to guarantee all the losses of the private sector. The normal functioning of the market will be put to one side. Bankrupt companies should be kept afloat by central government subsidies, loans and guarantees. He continued:

“While different European countries have varying financial and industrial structures, the only effective way to reach immediately into every crack of the economy is to fully mobilise their entire financial systems: bond markets, mostly for large corporates, banking systems and in some countries even the postal system for everybody else. And it has to be done immediately, avoiding bureaucratic delays. Banks in particular extend across the entire economy and can create money instantly by allowing overdrafts or opening credit facilities.”

The government must immediately reach into “every crack of the economy”, avoiding “bureaucratic delays”. For decades, we have been told that governments are inefficient, wasteful and should keep their fingers out of the economy as far as possible. Now, suddenly, being threatened with the complete collapse of the system, Draghi and his fellow bourgeois want the state involved in every part of the economy, ignoring all the regulations and laws that they have introduced over the past four decades. The state is quickly becoming the guarantor of the entire economic system.

Central banks to fund government expenditure

In the past, economists insisted on a strict separation of central banks and government. In their enthusiasm to ensure the independence of the central bank, they even introduced this stipulation into constitutions, such as the Maastricht treaty. This was to stop the central banks becoming a tool of fiscal policy, and essentially become guardians of a frugal fiscal policy. This is now being turned into its opposite.

In the past, economists insisted on a strict separation of central banks and government. In their enthusiasm to ensure the independence of the central bank, they even introduced this stipulation into constitutions, such as the Maastricht treaty. This was to stop the central banks becoming a tool of fiscal policy, and essentially become guardians of a frugal fiscal policy. This is now being turned into its opposite.

In an article in the Financial Times, Philipp Hildebrand, the vice-chair of the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock, explained the rationale. The interventions that central banks made to deal with the last crisis, mean that “the space for conventional and unconventional monetary policies is largely used up”. Instead, fiscal policy (government budgets) will have to shoulder the burden. But that is problematic:

“Left to its own, vast government spending will eventually lead to bond yields rising, making sovereign debt harder to raise and more expensive to finance. This would also risk creating a large public debt-servicing crisis down the road.

“That is why the policymaking world must evolve to a less simplistic understanding of central bank independence.”

[…]

“[T]o deal with this existential threat to the very foundation of the world’s economic system, a truly independent central bank needs to be confident in its ability to explicitly coordinate with other organs of policy, such as the state.”

What he’s saying, in plain speech, is that governments cannot borrow infinite amounts of money, because eventually the lenders will stop believing that the government can pay back the money. This will mean that they will ask for higher interest rates, and make further borrowing increasingly expensive or even impossible. To solve this, the central banks must “coordinate” – in other words, provide the government with credit. How does the central bank do that? By creating new money. In summary: the central bank must print money to fund government expenditure.

For more than 80 years, the ruling class has avoided this particular measure. Why? Because of the very high risk that it will lead to hyperinflation. These days, they think they are very clever and have learned all the lessons and therefore this will not happen, just like Gordon Brown was boasting that he had ended the boom-bust-cycle.

Central banks have already been carrying out this policy. The Federal Reserve for example, holds around 10 percent of US central government debt. The ECB, which faced a severe run on government debt a few years into the crisis, bought up €1.9tn worth of government debt over four years through its national central banks. This is somewhere in the region of 20 percent of all eurozone government debt. Now central banks are preparing to expand this much further.

The ECB, which was meant to be constitutionally restricted from supporting government deficits, has announced its €750bn bond buying programme, declaring that it will help any of its constituent governments lower their borrowing costs. The Federal Reserve has declared its buying of treasury securities essentially unlimited, with a first tranche of £375bn being bought last week. Legislation is being prepared to allow the Fed to buy not just short-term government securities, but also long-term as well as state and municipal bonds. Effectively, the central bank is going to bankroll the whole US government for the coming year. This is without precedent.

A national bank

Not only is the central bank going to fund government budgets, but it is also going to take over the role of the commercial banks. Defaults on mortgages, bankruptcies of companies etc. are going to put a strain on the ability of commercial banks to lend more money, even if they wanted to.

Into the breach steps government and central banks. The German government has given the green light to €800bn of loans from its investment bank. The $2tn US rescue package includes $850bn of funding for loans to businesses, including $350 for small business. The central banks are also stepping up their activities.

The Federal Reserve has announced another set of measures aimed at solving the debt markets that have broken down. It has announced the purchase of £250bn worth of mortgage securities. It is even preparing a Main Street Business Lending Program that aims to reach small and medium-sized businesses. This is to ensure that apparently unlimited credit is available to businesses of all sizes. As the chief US economist at JPMorgan put it, the Federal Reserve is turning itself into a commercial bank instead of a central bank.

A system in a deep crisis

All the measures that the ruling class are taking have a clear aim: keeping all the businesses and workers on life support until the pandemic is over. Yet, there is no reason to see this crisis as a passing thing. It is the end of the road for a system whose life has been artificially extended for decades.

All the measures that the ruling class are taking have a clear aim: keeping all the businesses and workers on life support until the pandemic is over. Yet, there is no reason to see this crisis as a passing thing. It is the end of the road for a system whose life has been artificially extended for decades.

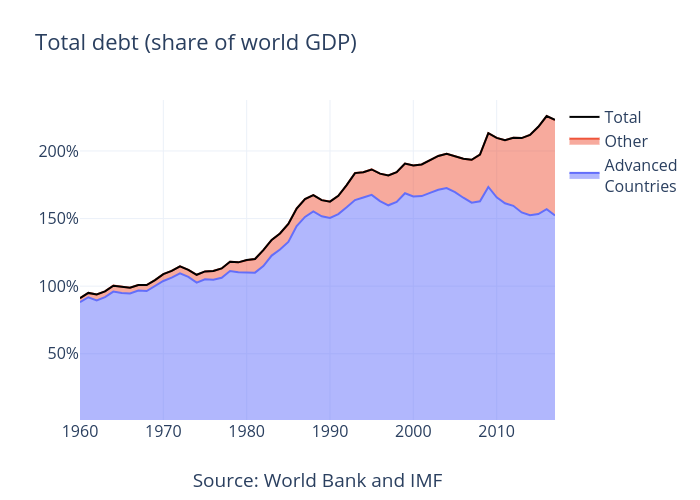

The expansion of credit did not begin in 2008-2009, but much earlier. The way that the capitalists got out of the crisis of the ‘70s is what has prepared the way for a much bigger crisis today.

The debt was a way of overcoming a crisis of overproduction, to ensure that companies kept investing and individuals kept consuming even when they couldn’t really afford to do so. But the expansion of credit eventually reaches a limit. You can only put off the evil day for so long.

We have explained this in a number of articles over the past decade. This is not a crisis caused by a virus, it is a crisis triggered by the virus. The pandemic only reveals all the fault lines that were there before.

Many economists and politicians hope that, after a brief sharp downturn, the economy will recover, and probably if this pandemic had appeared some decades ago that would have been the case. The system would have been able to recover relatively rapidly. However, now things are quite different.

The German and Japanese economies were already in recession and the effects of Trump’s 2018 tax cut stimulus package had started to wane in the US. The Chinese economy had shown signs of slowing down already after its unprecedented expansion of credit was yielding decreasing returns. The trade conflicts initiated by Trump had put a serious dent in international trade. The recovery, in the sense there was one, had come to an end.

Therefore, the measures they take now are unlikely to be of a temporary nature. Rather, the state will have to continue to support the economy for years to come, because it would have been forced to do so even without the pandemic. This reflects the fact that the productive forces have far outgrown the limits of private ownership. Capitalism can no longer play a progressive role, and the only way the bourgeois can patch up the system is by letting the state take over.

The comparison with war time economies of the two world wars is apt. It was precisely in the period between 1914 and 1945 that capitalism found itself in another similar crisis, although this crisis is going to be deeper.

Yet this will not come without a price. In spite of the wishes of the defenders of capitalism in the labour movement, there is no free money. The policy they have now adopted would, until 2008, have been considered madness, and not without cause. Printing money whilst productive capacity is static or even declining will create inflation. Doing so in an uncontrolled fashion will create hyperinflation. This is one of the mistakes of the economic policies of Venezuelan president Maduro. It is also what the government of Germany famously did in the early 1920s, leading to a revolutionary crisis.

For the past decade, it has not had that effect, but that was on the one hand because they largely handed over the vast sums of money they created to corporations, and it didn’t really reach the real economy but mainly caused various kinds of asset bubbles. In addition, the economy was in such a depressed state that the measures central banks took avoided deflation, rather than creating inflation.

What they are proposing now is more far reaching, both in scale and scope. Central banks are intervening more directly, as are governments. At the same time, the problem isn’t just a lack of demand, as they call it, but in many markets also a lack of supply. Because of the pandemic the productive capacity is collapsing and it is unclear how much of it will be recovered. Capitalism is an anarchic system, which will not allow itself to be planned and controlled. In times of crisis, it becomes even more ungovernable, difficult to predict and chaotic.

There is already inflation in essentials like toilet paper, medical equipment and food. This can easily occur in other sectors as well that face disruption or rapidly shifting consumption patterns. This will only get worse.

Who will pay?

Eventually, someone will need to foot the bill for this. The bourgeois have all now become “socialists” in that they are keen for the state to bail them out but they will naturally try to lay the bill at the feet of the working class, asking them to pay.

Eventually, someone will need to foot the bill for this. The bourgeois have all now become “socialists” in that they are keen for the state to bail them out but they will naturally try to lay the bill at the feet of the working class, asking them to pay.

The actions of the airlines show the attitude of the bourgeois. Multi-billionaire Richard Branson asked for a bailout from the state for his Virgin Atlantic, at the same time as he asked employees to take unpaid leave. The cost of the wage bill of Virgin Atlantic would be something to the tune of £4m per week, which means that Branson’s £4bn could afford to pay the bill for about 20 years, even without state support.

If they go down the route of printing money to cover the debts, it will merely create inflation, which will cut into wages of the workers and the savings of the slightly better off workers.

The bourgeois is aware of the difficulties. They included a $1,200 cheque to all US residents as a means of blunting potential criticism of the corporate bailout. As the Wall Street Journal put it last week:

“Some in Congress are pushing to ensure cash payments to every American taxpayer be included along with industry aid, an idea that gained momentum Tuesday with President Trump’s endorsement. Such payouts would be popular, and would likely blunt criticism about aiding business.”

This will blunt the criticism, for the moment, but it will be very difficult, in a year or two, to argue for yet another austerity package to pay for the bailouts.

Ben Barnake intimated that he was surprised that the 2008-2009 bailouts didn’t provoke mass movements, a “populist backlash” as he calls it. But they did, it was merely delayed. The past few years have been one of intensifying class struggle everywhere. This latest crisis will only add fuel to the fire. Whatever means the bourgeois will use to attempt to patch up the system will prepare a wave of class struggle.