Research carried out by the University and College Union (UCU) reveals the extent to which university and college management in the UK are engaging academic staff on insecure contracts. But the reality of working in HE institutions is not only one of job insecurity, but also one of low pay and increasing workloads.

Research carried out by the University and College Union (UCU), reported on the front page of the Guardian earlier in November, reveals the extent to which university and college management in the UK are engaging academic staff on insecure contracts.

Using data compiled by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) for 2014-15, UCU calculated the proportions of academic staff engaged on fixed-term contracts of employment and casual ‘worker’ contracts (which are typically hourly-paid contracts and carry fewer rights and protections than contracts of employment) at universities and colleges of higher education (HE) across the UK. They found that, on average, 53 per cent of all those providing teaching and/or research are engaged on an insecure basis, with the highest proportion among the so-called ‘Russell Group’ of universities (58.5 per cent), followed by the ‘other pre-92’ universities (55.6 per cent) and the ‘post-92’ universities (44.5 per cent).

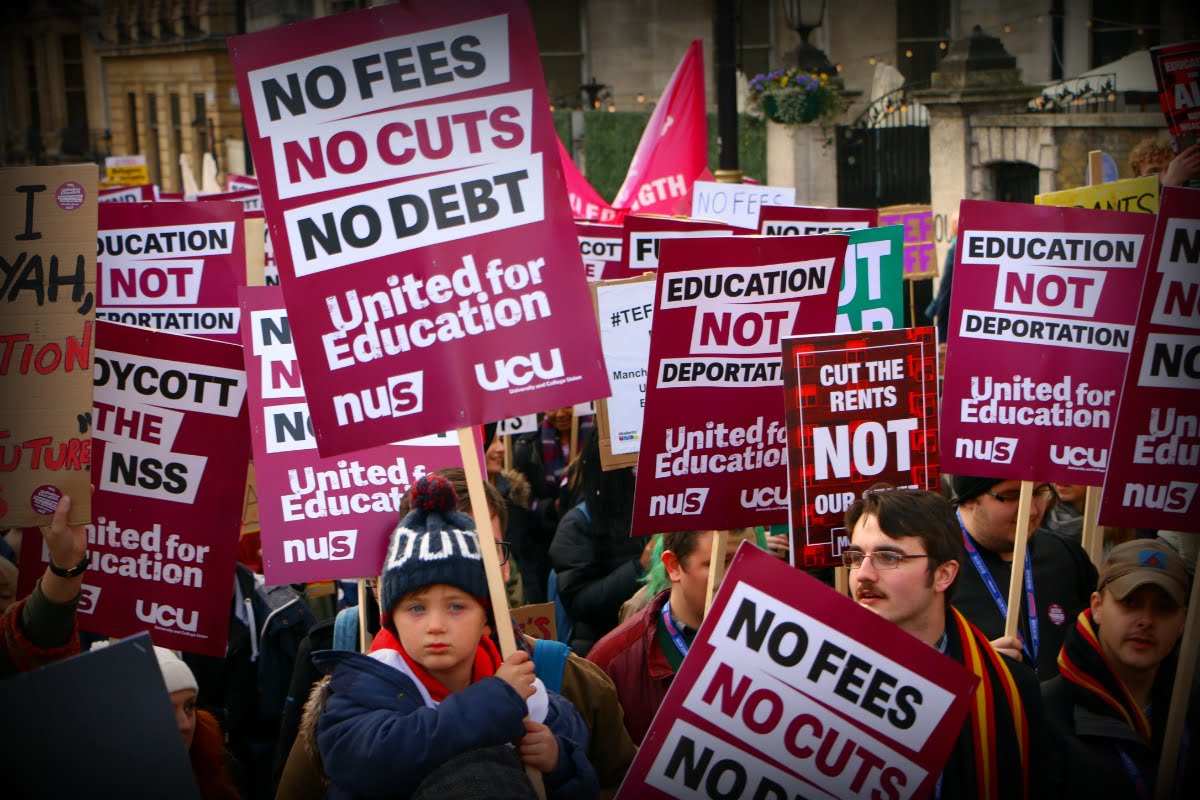

The findings have led to UCU launching a campaign called Stamp Out Casualisation, which included a national day of action on casual contracts on 19 November during its national recruitment week.

Typically, workers at the bottom of the academic hierarchy are the ones who are engaged on an insecure basis: for example, teaching and research assistants, associates, and fellows – roles often undertaken by research students having to work to fund their degree course. However, as the three case studies reported in the Guardian show, the casualisation of the academic labour force is extending to the ranks of lecturers, who now find themselves unable either to make long-term plans – for example, to purchase a house or start a family – or to build a career.

But the casualisation of working conditions in the higher education sector is just one way in which workers are being exploited. As the three case studies reported in the Guardian show, the reality of working in higher education institutions in the UK is not only one of job insecurity, but also one of low pay and increasing workloads.

With regards to pay, a survey of UCU members engaged on a casual basis in universities and HE colleges in 2015 (‘Making ends meet: The human cost of casualisation in post-secondary education’), revealed that 17 per cent of respondents struggled to pay for food; 34 per cent struggled to pay rent and make mortgage repayments; and 36 per cent struggled to pay utility and repair bills.

With regards to workload, another survey of UCU members working in the HE sector in 2014 revealed that 79 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they found their job stressful, compared with 72 per cent in 2012, while 48 per cent reported that they experienced unacceptable levels of stress ‘always’ or ‘often’, compared with 39 per cent in 2012. It also showed that 41 per cent of respondents who were employed on a full-time contract worked more than 50 hours per week, compared with 34 per cent in 2012, and that 15 per cent worked more than 60 hours per week, compared with 10 per cent in 2012. These findings led UCU to launch another campaign called Workload is an Education Issue.

These unprecedented attacks on academic pay and working conditions are a symptom of the ongoing crisis of capitalism. As charities, universities and HE colleges depend on publically-funded capital grants to meet their needs for investment. However, with public spending being slashed and tuition fees already at eye-watering levels, the only way they can ensure that they have enough income to sustain investment in infrastructure and compete successfully for students is through increasing the size of their surpluses; and the only way they can do this is by reducing pay and increasing workloads. However, because universities and colleges are operating in a market, demand for research and teaching can fluctuate. This is why the bosses, represented by the Universities and Colleges Employers Association, want their workforces to be as cheap and as flexible as possible; it is why they think of universities and HE colleges as akin to private-sector businesses.

What is needed to address the crisis of insecurity, pay, and workload in higher education is more than just another campaign, which can only draw attention to the symptoms of the problem. What is needed is a solution that addresses the underlying cause of the problem. Removing the internal market from higher education, as the union leaders propose, is not a solution to the long-term problems facing the HE sector as a result of the fundamental cause of the crisis: the capitalist system.

Education workers – and the working class in general – require a political alternative from the leaders of the labour movement; a bold socialist programme, so that universities and colleges can be run democratically and academic workers can be treated decently, as part of a general plan of production, in which education and the wider economy are run in the interests of the many, and not simply for the profits of the few.