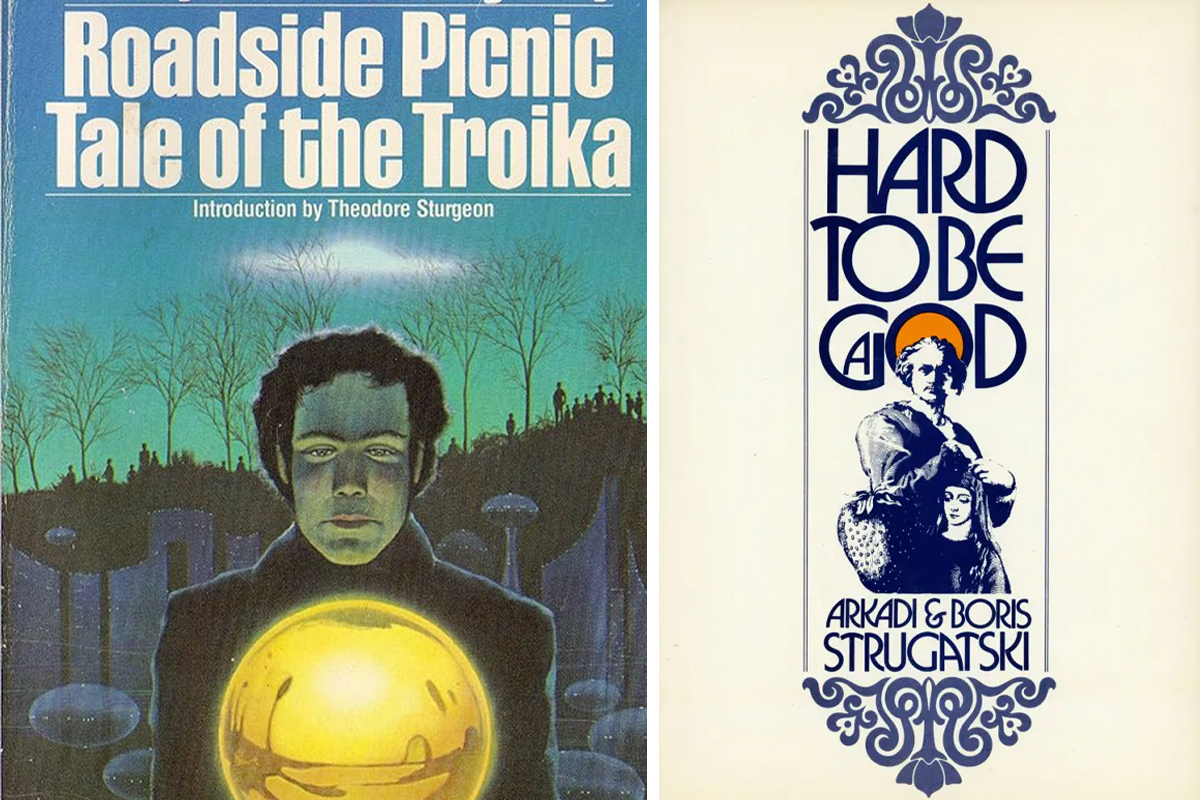

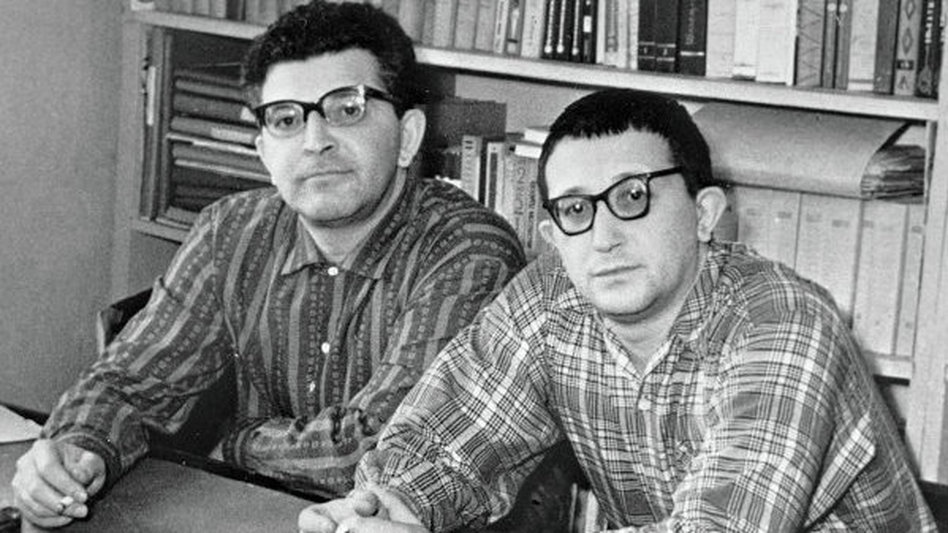

Roadside Picnic (1972) is perhaps the most famous of the works of Soviet sci-fi authors Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Most notably, it inspired Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 masterpiece, Stalker.

Unlike their more whimsical and comic works, such as Monday Begins on Saturday, the world depicted in Roadside Picnic is a bleak and desperate one.

The central premise is that 30 years prior to the story, alien life visited Earth for two days, and then left. In the six sites where they landed, they left behind all manner of incomprehensible alien scrap.

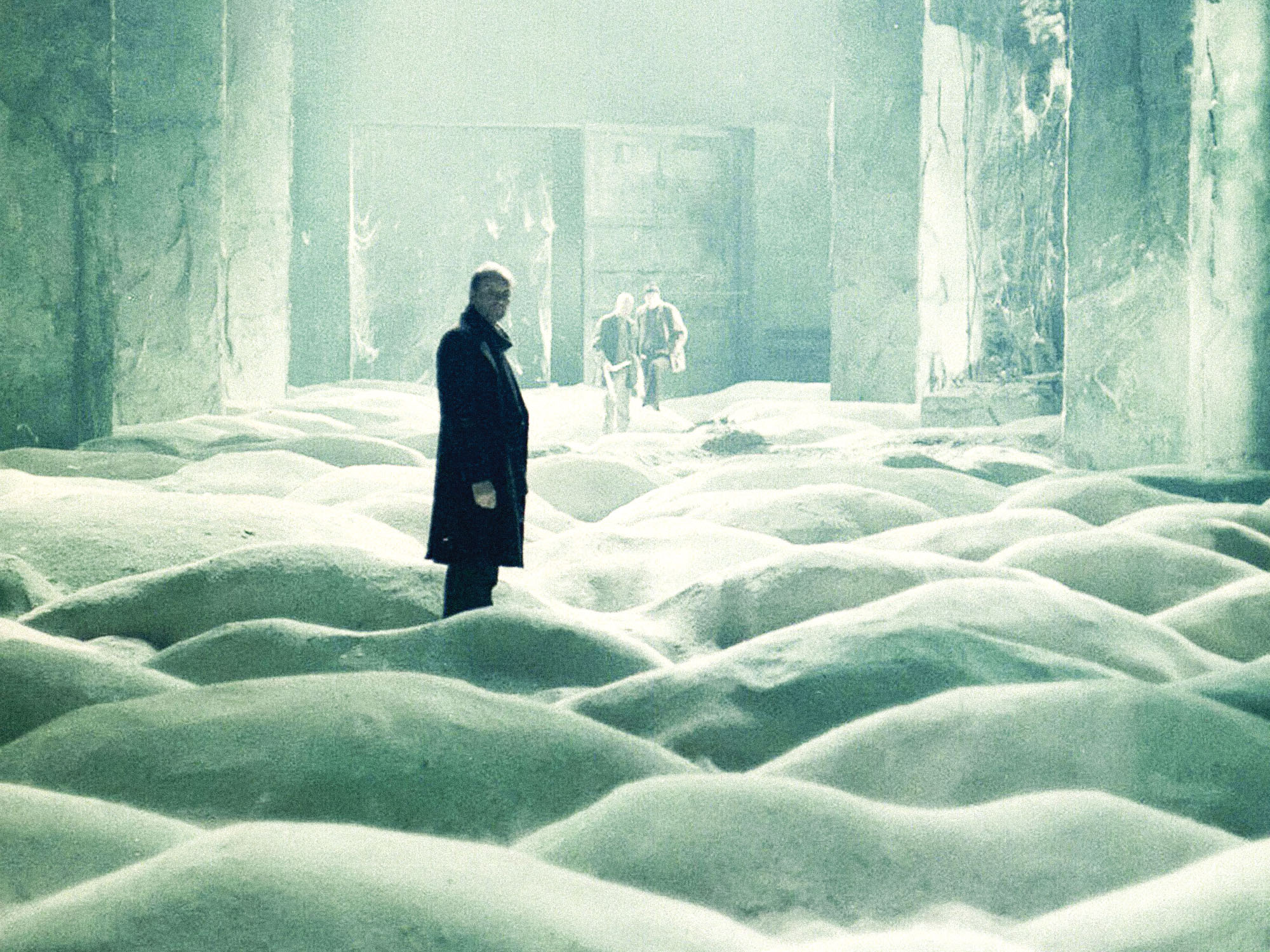

Whole towns have since popped up around these sites, called ‘Zones’. The government has cordoned off these zones, and has sole access to the salvage within.

However, there is a black market for the salvage, gathered by ‘stalkers’ who sneak in and risk life and limb to retrieve it and sell it on.

The book paints a colourful picture of a gallery of rogues and criminals, all of whom live off the Zone in one way or another. You meet violent alcoholics, corrupt politicians, and desperate criminals who will happily stab you in the back to make a quick buck. The protagonist is one of these rogues.

Man and nature

Typically, stories about alien visits highlight the deeper meaning of our interaction with them. Whether it is to subjugate the earth, or to enlighten humanity with higher knowledge, we have been actively sought out for a higher purpose.

Roadside Picnic takes a different approach. A lot of time is given to the debates around the nature of the visit, with some claiming that it was a planned intervention to accelerate human development with advanced technology, with others painting the aliens as harbingers of doom.

There is a general propagation of mysticism, alongside a decline in the stature of science as a result. It touches on historical precedent: what is not understood, is ultimately imbued with otherworldly properties and powers.

The title of the book comes from an analogy drawn between the visit and a picnic by the roadside, where all manner of scraps of food, old tools, and other debris are left behind.

Only after the picnic has ended and the travellers moved on does the local wildlife venture forth to see the aftermath. Humanity is put into the place of being a microcosmic part of a far bigger picture – just an intergalactic stop-off for some other species on its journey to a further destination, thinking little of where they stopped.

There are strong themes of the relationship between humanity and the natural world. The impacts of industry and technology on the environment and how this can in turn act back upon us.

It is a stark reminder that we do not stand above nature as a conquering force, but are an active part of it.

There are obvious parallels to the climate crisis, and the impact of industry and so on established without regard for its harmony with nature.

Written during the Cold War, where the threat of nuclear war loomed, it is not hard to see where ideas about the potential devastation that could be brought on by new technology could have on the world came from.

It is no coincidence that those who entered into the Chernobyl exclusion zone, following the 1986 nuclear disaster which devastated the environment around it, referred to themselves as ‘stalkers’.

Radiation and its long term effects must have been on the minds of the Strugatskys; any contact with items in the Zone can lead to deadly consequences, even things as innocuous as a cobweb, or a shadow that doesn’t quite look right.

The horror and uncertainty surrounding even the most unassuming of things does a good job of portraying the surreal fear of something totally unknown to us – the Zone feels truly alien, which is something that not many science fiction works manage to pull off.

It does this not through the invention of new names or fantastic cultures and species, but by taking the most mundane and expected of objects and making them incomprehensible, totally outside of human reason, something that subverts one of the most basic human relations: understanding.

Even the form of the book lends itself to this: it explains absolutely nothing. You are dropped into the world, and expected to adapt to its conditions.

The book could be taken as something of a cosmic horror, so gritty is its depiction of just how grim life in the fictional town is, as well as the unknown.

Living in the presence of the Zone has led to the mass proliferation of birth defects and mutation amongst children born. This includes the daughter of the protagonist, a monkey hybrid which becomes less human as the plot progresses.

Whilst the town is fictional, the world that it depicts certainly is not.

It evokes clear parallels of the mass destruction of the USA’s dropping of two nuclear bombs on Japan in 1945. As well as its use of the chemical weapon Agent Orange in the Vietnam War.

Both claimed thousands of lives, and both left vast swathes of land uninhabitable, and continue to be the cause of birth defects and health issues today.

In the case of the atomic bomb, it demonstrates on one hand the pinnacle of mankind’s mastery over the natural world, through the splitting of the atom, and on the other the immense destructive potential this can have when used by the wrong people.

Critique of capitalism

Whilst clearly containing jabs at the Soviet bureaucracy, Roadside Picnic holds up a mirror primarily to capitalist society, and the horrors of war, oppression, and desperation that are paired with it.

Despite seeming very bleak on the surface, the book actually contains a very positive message. It is the cruel and hopeless world, brought on by the insatiable need for profits, that has produced a generation of cynical, greedy, and violent people.

Under the surface level of things, these people are not wholly good or bad, for they are shaped by their conditions. The theme of a higher purpose, or goal, that threads through the everyday hardships is present throughout the book.

It paints a very contradictory picture, our protagonist is motivated partially by a want to get rich, partially out of a want to stop his daughter’s regressive illness, and partially for reasons that he himself is unable to quantify.

The Zone is both a destructive and a creative force, it is deadly and yet has an alluring beauty. The technology left behind has both the potential to throw back humanity and to fast-track human development, boosting our technological level.

What matters is not the technology itself, but how it is utilised by the society that absorbs it. In this are the seeds of both regression and progress.

Within the Zone somewhere is allegedly a golden orb that is said to grant your deepest, darkest subconscious wishes if it is to be found, an almost on-the-nose metaphor for this idea.

Contrasted with the cruel and repressive world on the outside, it is no wonder that the stalkers are driven to the Zone, despite the dangers within. Without spoiling the ending of the book, this reflects a key theme throughout.

Soviet censorship

The Strugatsky brothers went through an eight year long process of negotiation with the Soviet censors before the book was widely released, despite the fact that it paints a vividly negative picture of capitalist society, not Soviet society.

Amongst the usual censoring of language, a demand of the censors was to “get rid of the bleakness, hopelessness, coarseness, [and] savageness” of the world depicted.

The early 1970s was a period of crisis for Stalinism internationally, as various Stalinist regimes split along national lines, and the Soviet economy began a long period of stagnation.

Perhaps a work that depicts the harsh struggle for existence, and the arbitrary rule of unaccountable bureaucrats hit a bit too close to home for the Soviet censors.

That aside, it mainly reflects the stifling influence of a conservative bureaucracy in art and culture, which imposes its platonic ideal of ‘soviet art’ upon the cultural creations of its people. Rather than allowing it to hold up a mirror to society, it attempted to filter it.

Roadside Picnic gives a ‘warts and all’ depiction of society how it is, even down to the use of slang and more colloquial language. This ran into the pearl-clutching conservatism of the censors.

Writing about this in an afterword to the book, Boris Strugatsky recounts the constant back and forth around foul language, stark depictions of oppression and violence, and the general bleakness of the novel. Replying to the censors, he wrote:

“A man who is well brought-up may read anything. The only people who boggle at what is perfectly natural are those who are the worst swine and the finest experts in filth. In their utterly contemptible pseudo-morality they ignore the contents and madly attack individual words.”

It is true that the meaning of the book’s content was missed, not just by the Soviet censors but by the critics of today who see only the crude language and unadorned depiction of prejudice and oppression.

Roadside Picnic is not a pessimistic fable about the worst that humanity has to offer, but a statement that even in the worst of conditions, and amidst the worst trappings of society, there is something fundamentally good and collective in our species.

‘Roadside Picnic’ is available to buy at all booksellers.

‘Hard to be a God’: The struggle for a communist consciousness

Nick Whittaker, Bradford

Hard to Be a God (1964) was among the first sci-fi novels of the Strugatsky brothers. Unlike western sci-fi, Soviet sci-fi wasn’t a small niche for dreamers – a decade later, the Strugatskys were known by all in Russia, their novels read to tatters by the masses.

This book was written in a contradictory time, when Stalinist censorship was rife but Soviet sci-fi still strove to tell of the communist future that people hoped was being built from present-day hardships.

From that perspective, the story being set on an alien planet stuck in an era of feudalism might seem strange – and feudal lord Don Rumata as a protagonist, even stranger.

However, as the novel’s foreword explains, Rumata is really Anton, an emissary from a future Earth where communism has triumphed. Rumata/Anton is an operative working on behalf of Earth historians, studying ‘the feudal mores of the planet with a view to assisting them to “progress.”’

In the Kingdom of Arkanar, Anton soon realises a period of harsh, brutal reaction is emerging – promising to derail any such ‘progress’ with bloodshed and a return to barbarism.

Yet Earth’s historians – operating from the standpoint of ‘basis theory’, an imagined development of historical materialism – argue that Arkanar is merely entering into a period of feudal absolutism.

This is the first hardship of ‘godhood’ that is alluded to in the title: even with all the knowledge and material means a communist future promises at his disposal, Anton feels incapacitated; incapable of doing anything besides saving ones and twos.

It is through Anton’s laments about his inaction that the real hardship at the heart of the story is revealed: the struggle between the communist spirit and the social conditions of feudal barbarism.

As the situation develops in Arkanar, the lines begin to blur for Anton between his identity as an observer for communist earth and lord in the Arkanarian feudal system.

At one point, he is described as ‘no longer a communard.’ Later still: ‘he was no longer playing the role of a highborn boor but had largely become one. He imagined himself like this on Earth and felt disgusted and ashamed.’

The novel alludes to many other themes, including the real-world censorship taking place. The antagonist Reba, for instance, was originally called Rebia – an anagram for Beria, one of Stalin’s successors who oversaw mass killings and purges by the secret police.

But the novel shines brightest when focusing upon Anton’s internal struggle. As Marx explained, “it is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

To watch the struggle between a communist consciousness and the impact of barbaric conditions where, in the words of Marx, ‘all the old crap revives’ is why communists should read Hard to Be a God.

‘Hard to Be a God’ is available to buy at all booksellers.