‘Severance’ – alienation in the workplace

Charlie Edwards, UEA Communists

The second season of office drama/sci-fi thriller Severance has recently concluded, receiving mass acclaim from audiences.

The series follows four office workers who have had their minds surgically split in two. One part of the worker’s consciousness only experiences the inside of the labyrinth of the Lumon Industries office, the other part of the consciousness only experiences the outside world, completely unaware of the other’s memory.

Not only does this serve as an interesting plot device for our protagonists Mark, Helly, Irving, and Dylan, but it serves as a powerful metaphor on alienation in the workplace.

The ‘innie’ and the ‘outie’ as they are referred to in the show are literally two different people.

The ‘innies’ themselves are subject to a brutal life of endless work – they never sleep and only get to eat on special occasions where they have completed special files on their workplace computers.

The workers have no idea what they are working on when they are tapping away on their computers and if they ask they are told by management that “the work is mysterious and important.”

The managers are trained by the company to act like sociopaths to the ‘innie’ employees and often play psychological games to make sure the workers act in line.

On top of this, the workers are also subject to propaganda about the corporation’s founder Kier Eagan, essentially elevating him to the status of a God who’s watchful eye is always watching over the workers.

Marx wrote extensively about the effects of the capitalist system on the psychology of the working class, writing: “The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home.”

Severance is able to really capture the essence of how the capitalist system dehumanises workers and creates barriers between genuine human connection. Both the ‘innies’ and ‘outies’, shaped by their work at Lumon Industries, are often shown unable to form genuine connections with the people around them.

It’s no surprise that Severance has resonated deeply with working-class audiences – it’s a gripping series!

‘Severance’ is available on Apple TV+

‘On Falling’: isolation, alienation, and work

Ben Cownley, Manchester

Laura Carreira’s first feature film, On Falling, centres around a warehouse worker and the cost her job has on her life. It’s a sobering study and well worth a watch.

From the beginning, it’s clear this warehouse operates as a dehumanising machine – we watch as people sink into the rhythm of it, the beeps and clicks of hundreds clocking in for work. It’s a place devoid of anything but the bare necessities for getting the work done; even the lights struggle to work.

The main character, Aurora, lacks any personality that we can see, which I think is the point. She is a quiet Portuguese woman, living in shared housing with strangers, isolated and numbed to the point that even as the audience we learn almost nothing about her.

What we do see is her constantly struggling with money, stress-eating, and distracting herself with her phone after an exhausting, lonely day at work.This is someone struggling to be a person; always at arms length from others and having nothing to share.

The warehouse is obviously an Amazon-lookalike, where everything runs according to a set system with no exceptions, the workers are paid poorly, and the conditions are alienating.

The big higher-ups are constantly pushing for tighter and tighter deadlines, and then reward the workers with sweets and cake for making them millions. When there are tours of the warehouse, it reminds you of a trip to the zoo, with Aurora and her coworkers as the animals on display.

This is a film bluntly about alienation and being a part of a machine that is only concerned with squeezing more profit out of people.

The film sums up the grim effects of this quite nicely when Aurora, hoping to break out of the drudgery, eventually interviews for a better job.

The interviewer asks her to ‘tell me about yourself’ and Aurora struggles to answer the question – aside from being at work and going on her phone, she doesn’t do much else. She lies about her hobbies instead, using bits she’s picked up from work.

Exhaustion, low pay, and long hours stripping people down to just their job – with no ability to pursue anything like a hobby, or even form connections with the people around them – is something many in the audience will know first hand.

On Falling does strive to inject some moments of warmth and hope into what is quite a bleak picture. But more than anything, what these achieve is to underline just how accidental and fragile these are, so long as this system of unrestrained exploitation which asset-strips the self remains.

‘On Falling’ is showing in selected cinemas now.

What we owe to the world at our feet

Maria Sverdlova, Bow

I recently visited ‘SOIL’, an exhibition currently on show at Somerset House. Using artwork, documentary evidence and scientific artefacts, it explores the connection between man and nature, and how much we owe to the world beneath our feet.

What the exhibition gets across very well is the fact that modern agriculture is sapping the soil of its health and useful properties. The most fascinating and memorable pieces in the exhibition were exactly those that acknowledged how it is the current system of production that is unsustainable, not that this was just a matter of humans ‘taking nature for granted’.

View this post on Instagram

The curators, however, skirted around calling capitalism by its name, referring only to “industrial agriculture”.

We need to call it what it is – it is capitalism that is destroying our planet!

If it wasn’t for the profit motive standing in the way, the massive progress in science and technology that humanity has achieved would allow us to reap the fruits of nature without destroying the long-term vitality of our ecosystems.

In Capital, Marx very correctly wrote that “all progress in capitalistic agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the labourer, but of robbing the soil”. Go and visit this exhibition with this thought in mind, get inspired by the beauty and complexity of soil, and let’s fight to take nature’s wealth into our own hands!

‘SOIL’ is on show at Somerset House in London until 23 April 2025.

The state vs class struggle

Tom Wood, Liverpool

I recently picked up a copy of Des Warren’s The Key to My Cell.

Des was part of the ‘Shrewsbury 24’, imprisoned for his role as a picket in the national building workers’ strike of 1972. The book goes into great detail of the sacrifices Des made in the fight against the bosses.

The whole apparatus of the state came down upon this man for what he represented – uncompromising class struggle in the face of the Tory’s systematic attack on basic trade union rights!

You cannot put the book down as Des describes the victimisation of the picketers, and the conspiracy between the bosses, the state, and the labour bureaucrats to undermine the class struggle that was breaking out.

The same is true as he describes altercations he had with prison guards and police, many of whom supported the fascist National Front. More intimate, personal accounts demonstrate him having been a loving father and husband.

Reading his words, you feel yourself alongside Des and wish desperately for him to be freed – which makes reading of the 1974 Labour government’s rejection of these requests all the more despicable.

Make no mistake: the state is responsible for the murder of Des Warren. He was chemically sedated repeatedly during his three year sentence to end his troublemaking, leading to him developing Parkinson’s Disease at only 38 years old.

It wouldn’t be until almost fifty years of campaigning later in 2021 – long after Des’ death in 2004 – that the ‘Shrewsbury 24’ would see their convictions overturned in court.

This injustice only leaves you all the more motivated to bring real justice for the likes of Des and the ‘Shrewsbury 24’ by overthrowing this rotten system once and for all!

‘The Key to My Cell’ is available through various second-hand booksellers.

‘The Ostrich’ – a song and a wake-up call

Michael Omatsola-Morgan, Birmingham

Steppenwolf are a rock band perhaps best known for their song ‘Born to be Wild’, from their 1968 debut album.

But on the same album, which was written just before the revolutionary events of 1968, you find ‘The Ostrich’ which is not just a song – it’s a furious, unrelenting wake-up call.

It thrusts the listener into the shoes of a worker jolted from the slumber of the so-called “American Dream,” only to find themselves in the throes of a capitalist nightmare. Alarm bells scream, lights flash, and suddenly, the comforting illusion shatters.

The world around them is crumbling, rotting under the weight of greed and blind obedience. When they search for answers, the voices of authority respond with hollow reassurance:

“But it’s alright. It’s progress folks, keep pushin’ till your body rots!”

Desperation takes hold. They plead with friends, with family – surely, someone else must see the horror unfolding before them. But no. They remain ensnared in their dreamlike stupor, muttering the same lifeless mantra before drifting back into oblivion:

“But there’s nothing you and I can do. You and I are only two. What’s right and wrong is hard to say. Forget about it for today. We’ll stick our heads into the sand, just pretend that all is grand. Then hope that everything turns out okay.”

The absurdity, the hypocrisy – it’s maddening. But the more they fight to make sense of the chaos, the more the system tightens its grip. And then, with a sinister grin, Uncle Sam himself steps forward, the embodiment of manufactured freedom:

“You’re free to speak your mind, my friend. As long as you agree with me! Don’t criticize the fatherland, or those who shape your destiny.”

The threat is not subtle; it is a blade held to the throat of dissent. Fall in line, or watch everything you love be stripped away. The enforcers stand ready, a faceless army of “boys in blue” waiting to silence any voice that dares to cry out.

The story bears striking resemblance today where the cry of millions of workers and youth are screaming into the void of political leadership, begging for a way out of the crisis – only to be met with silence.

‘The Ostrich’ is available on Spotify and other streaming platforms.

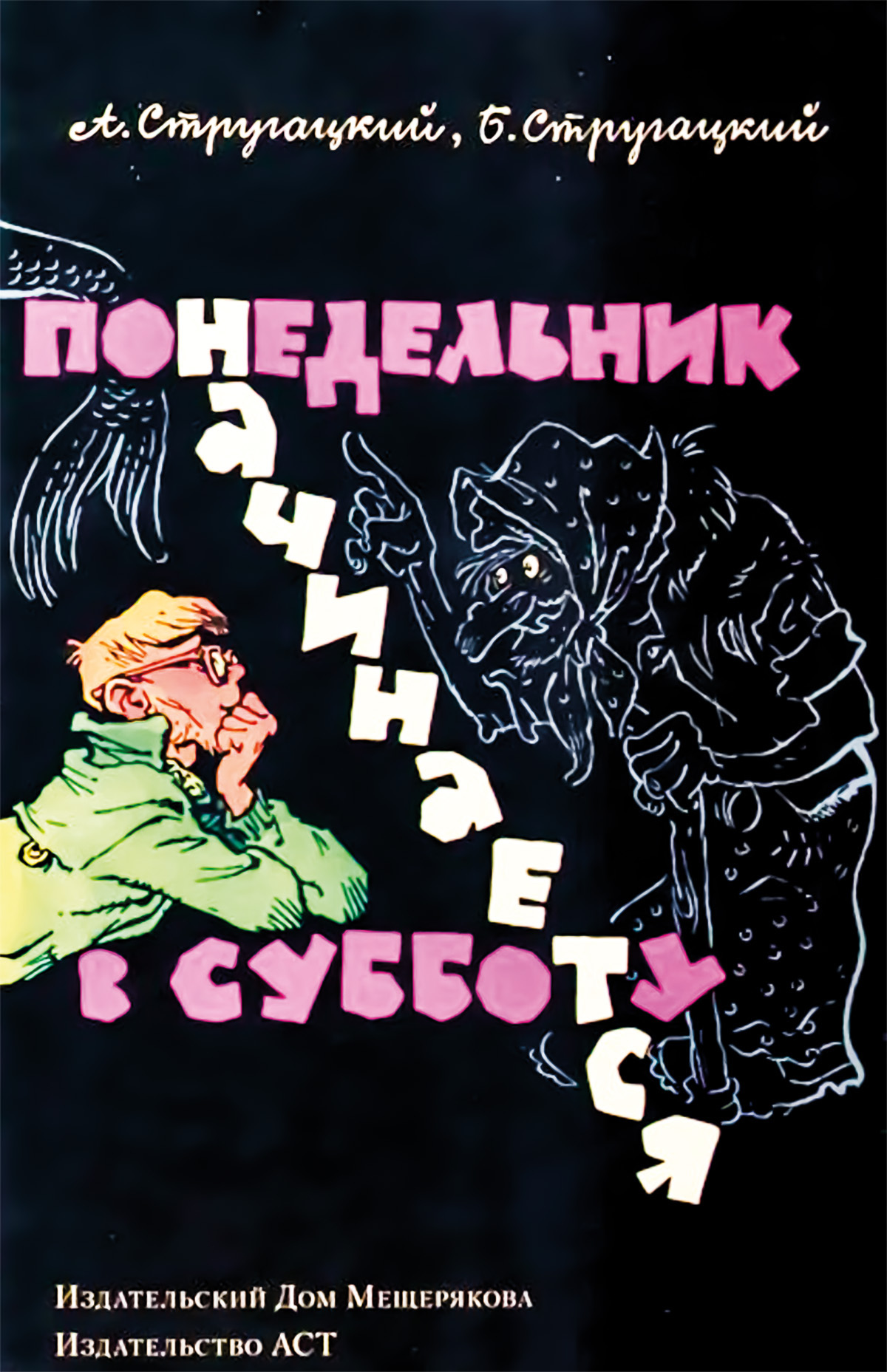

‘Monday Begins on Saturday’: absurdity, bureaucracy, and optimism

Sean Hodges

Science fiction tries to examine possible futures, or the present via an imagined allegorical future. This makes it a popular genre, especially nowadays.

In the west, this often takes the form of ‘hard’ sci-fi – stories predominantly concerned with the plausibility and immediate implications of the science they present.

But in the former Soviet Union, especially during the Khrushchev Thaw of the 1960s, the balance was tilted far more towards social sci-fi, concerning itself with the development of human society and its effects on individuals. It was also often satirical in content.

It is to this latter tradition that Monday Begins on Saturday belongs. Written by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and first published in 1965, it blends science-fiction and fantasy in a series of vignettes to subtly lampoon contemporary Soviet scientific bureaucracy.

Monday Begins on Saturday is, first and foremost, brilliantly funny. A knowledge of Marxism helps this along, but the book’s absurd yet sharp humour will land for all kinds of readers.

It tells the story of Aleksandr Ivanovich Privalov, a programmer who gains employment at the Scientific Research Institute of Sorcery and Wizardry (“the National Institute for the Technology of Witchcraft and Thaumaturgy” in the English translation).

That Pavlov manages this feat entirely by accident – he comes across a five-kopeck piece that keeps reappearing in his pocket once he’s spent it, thus drawing the attention of the authorities – is only the first of his difficulties.

A boastful, career-minded Merlin; a vampire janitor who isn’t allowed to drink tea unattended because “that’s not tea he’s drinking”; and a building where displaying a lazy attitude turns your ears hairy; the perils of a life in Soviet magical research are endless.

The Strugatsky brothers lived through the Second World War and the final years of Stalin’s rule as young men, and the influence of that period can be seen in this book.

The institute’s leaders are plodding and self-satisfied politicos, for example, often unintentionally hamstringing their more idealistic and hardworking underlings as a result.

Yet despite the constant bungling, boastful careerism, and insane demands, there is a streak of optimism in Pavlov and the more noble-minded of his coworkers.

For all the difficulties they face, the institute staff believe nevertheless that they are building the future – and that for people with such lofty ambitions, weekends don’t exist and “Monday begins on Saturday.”

The Strugatsky brothers succeed in telling a sharply satirical but ultimately thoroughly human story in this novel, one in which many of us – despite living under a capitalist regime rather than a Stalinist one – will find very familiar.

For those who haven’t dipped their toes into Soviet science fiction yet, this book is an excellent place to start.

‘Monday Begins on Saturday’ is available (with £3 off) at Blackwell’s and through other booksellers (at full price).