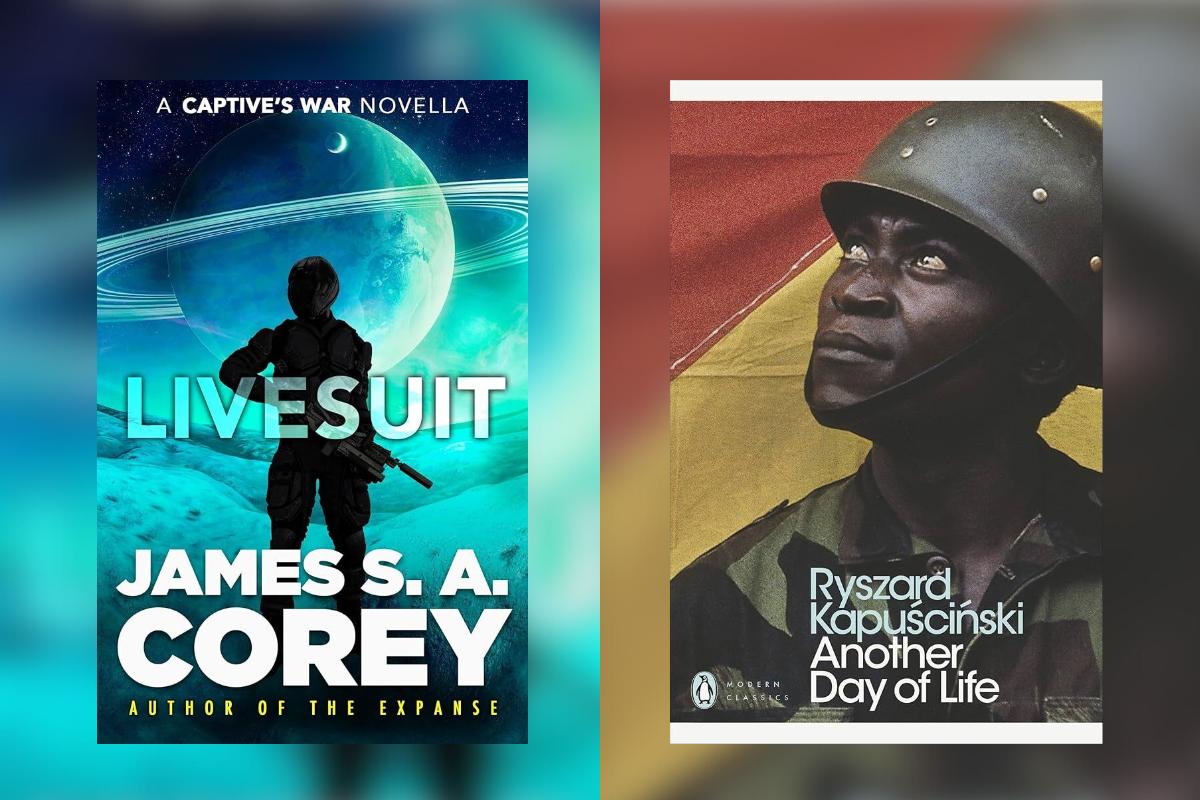

‘Livesuit’: the undying cost of war

Hugh Nankervis, Oxford

I recently read the 2024 novella Livesuit by James S. A. Corey.

Set in the far future, it follows soldiers equipped with ‘Livesuits’ – suits of near-living armour that makes them faster, stronger, and harder to kill – as they battle an alien menace hellbent on enslaving or exterminating humanity.

Whilst the worldbuilding is fantastic, especially given the length of the book, I believe the greatest strength of this novel is its portrayal of the alienation of soldiers as they function as living weapons in this seemingly endless war.

Livesuits cannot be removed for the duration of service, and they eradicate soldiers’ need to eat, drink, or perform any normal functions.

The semi-living matter which Livesuits are made up of also fully replaces any limbs and organs lost in battle; after five years of standard service, there is hardly any of the original soldier left.

Removed from everything that makes them human, these soldiers are, as S.A. Corey puts it, “an army of the dead”. And they are never going home.

LIVESUIT by @JamesSACorey is available now! This is the first novella set in the universe of the epic Captive’s War series and best read after The Mercy of Gods. pic.twitter.com/sGBBpnEW0E

— Orbit Books (@orbitbooks) October 1, 2024

The monstrous nature of the alien enemy is not questioned or doubted in the text. However, humanity’s military censor is omnipresent – suppressing knowledge of what it means to be a Livesuit soldier, and cracking down on protesters who seek to unveil the truth.

Most harrowing of all, a large incentive to join the Livesuit infantry is the money: they are offered hefty sums for completing a tour and bonuses for reenlisting.

For such a short story, Livesuit has a lot to say on the society of today as well as the future.

Researchers have identified two main categories of reasons for people to enlist: institutional (the desire to serve and protect their nation) and occupational (the chance to escape poverty and gain an education).

Both of these are ruthlessly exploited by the British armed forces, which had more than double the budget for recruitment than NHS England did from 2019 to 2021 – and more than three times the budget of the department of education for recruiting teachers!

And they don’t have the excuse of alien overlords at the gates.

While it is set on planets far away, the harsh reality of a soldier’s life under capitalism – to be a tool to be used up and thrown away – and the reality of welfare under imperialism, where healing and learning come second fiddle to war and death, hits all too close to home.

‘Livesuit’ is available as an ebook through its publisher, Orbit Books.

Is revolution just ‘Another Day of Life’?

Kara Jarvis, Ipswich

Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński was no stranger to revolutions, having experienced 27 first-hand throughout his life.

So in the summer of 1975, Kapuściński flew to Angola to record the final days of Portuguese rule in the region after the thirteen-year-long Angolan war of independence.

He subsequently wrote perhaps his best work yet: Another Day of Life, a non-fiction account of the Angolan Revolution and Civil War, published in 1976.

The People’s Republic of Angola was declared on 11 November 1975, freeing the Angolan masses from centuries of Portuguese subjugation – but a civil war rapidly broke out, lasting on and off until 2002.

Another Day of Life documents the build up to independence, and then the first few months of the civil war. Across the pages, Kapuściński writes in a remarkably unique style, forgoing the traditional removed, ‘neutral’ style of journalism for a personal narrative and sympathetic yet stark honesty.

He takes the reader on a journey, describing the environment in a whisper as much as a shout, inviting fragments of conversation from soldiers, revolutionaries, and even other journalists alike into his ink.

Kapuściński paints a particularly graphic picture of the tense, uncertain days of the civil war. This includes a powerful exchange with a sixteen year-old painter, who explains he signed up to the fight on the army’s promise they would help him go to school after.

Details like this provide a powerful demonstration of what revolutions mean for the downtrodden masses: the chance for a dignified and humane life.

Despite the honesty and integrity of Kapuściński’s journalism, he was clearly not a Marxist or a revolutionary. That by itself is not an issue; plenty of non-Marxist historians and non-fiction writers offer invaluable lessons for any communist.

Yet, as an account of a real life revolution, the book is undeniably held back by its inability to articulate the primary issue of the Angolan revolution: the deformed character of the workers’ state.

Despite the great victory for the masses that was the overthrow of colonial rule, true power was not yet in the hands of the working class, because power had not been handed to the workers.

Amidst the Sino-Soviet split between Maoist China and the Stalinist USSR, Angola soon became little more than a battling ground for the bureaucrats of Moscow and Beijing to assert their national interests.

Nonetheless, Kapuściński’s writing shines in the light of honesty at what he saw. His enticing style, full of shifts in perspective and a myriad of sources – from noted down conversations to telegrams – keep the pages flowing, and your attention held.

It is up to us today to draw the lessons from what Another Day of Life faithfully documents, and to fight for a successful socialist revolution in our lifetimes, both at home, and in all the oppressed nations of the world.

‘Another Day of Life’ is available from all booksellers.