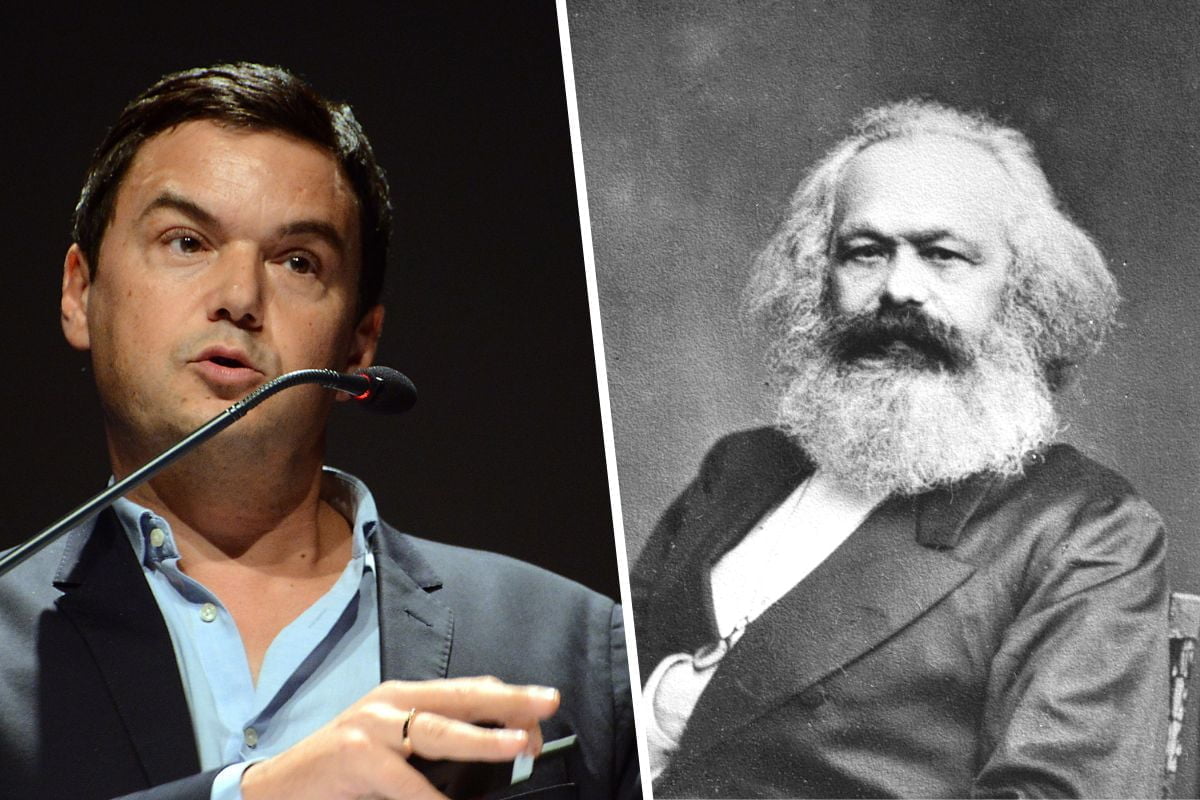

A new book on economics has hit the stands and has been making waves in the national and international press, not least among economic commentators.Capital in the 21st Century, by the French economist Thomas Piketty, has been at or near the top of the bestsellers lists in the USA for some months and has elicited commentary from even the most unlikely sources. Most of the serious journals of capitalism have devoted an editorial to it at one point or another in the last few weeks.

Can the real Karl Marx please stand up?

The title of the book is clearly an allusion to Marx’s most famous book, Capital, and some commentators have clearly drawn a parallel between the two. Writing in the New York Times under the by-line “Marx Rises Again”, one commentator describes Piketty’s work as one of the two pillars of the “current Marxist revival”. “Yes, that’s right”, he writes, “Karl Marx is back from the dead” and he describes Piketty’s book as the kind of synthesis that Marx himself once offered.

In fact, the book is anything but a Marxist analysis of modern capitalism. The author analysis offers no coherent theory and what there is bears no relationship to Marx. The labour theory of value, the foundation of Marx’s work, is nowhere to be found, nor, for that matter, is there any critique of Marx. The main thesis of the book is simply that the current gross inequalities of wealth across the globe are inherent in capitalism, that they are a source of economic and political instability and that the inequalities will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

Piketty’s own views on Marx are distinctly hostile but superficial. Linking Marx’s analysis of capitalism somehow with Stalinism, he notes that after its collapse in 1989, he “never felt the slightest affection” for the Soviet Union. Instead, he is an avid defender of the ‘free market’. Private property, he writes, “plays a useful role in coordinating the actions of millions of individuals”, which he contrasts to the “The human disasters caused by Soviet-style centralized planning”.

Tobogganing towards disaster with their eyes closed

Why, then, has his book caused such a sensation? The real answer is that from the point of view of most capitalist economists, Piketty is something of a maverick and he is clearly putting a line that is different to most of his contemporaries. The big majority of ‘official’ economic theories are completely at a loss to explain the nature and causes of the 2008 economic crash. Unlike the Marxists, most economists didn’t see the crash coming and they still don’t know where it came from. For them there is no ‘big picture’ at all.

As an editorial in The Guardian put it, referring to university Economics departments, “Honours are obtained, doctorates earned and tenure secured not by soaring up to see the big picture but more often by crunching endless data on this or that market, or postulating the arithmetic that supposedly governs particular relationships in very particular circumstances.”

So blind are the official schools of economic ‘theory’ that students and faculty members in many universities have even protested about the fact that their courses say absolutely nothing about the crash; lectures and economic courses continue blithely on as if 2008 hadn’t happened at all. There is now even an international organisation of students and academics which campaigns for university Economics faculties to open up to ‘alternative’ theories, including Marxist economics.

Piketty’s book has rattled cages because, although not a Marxist himself, he is repeating in his own words some of the arguments that Marxists have advanced for years. Most notably, Marxists have long argued that the great post-war boom that lasted up to the mid-1970s was no more than an aberration and that the later years of the twentieth century saw capitalism return to its ‘normal’ pattern of booms and slumps, with resultant mass unemployment and class struggle. Piketty has explicitly agreed with this general view, putting the golden years of the boom down to a series of fortunate but not-likely-to-be-repeated circumstances.

Shining a spotlight on inequality

Although he is by no means the first to point in that direction, what Piketty has also done, and in enormous detail, is to highlight the growing divisions in society between the haves and the have-nots. Indeed, this is the whole basis of his book. Much of the data he has collected, based principally on the USA, but also including Europe and Japan, is accessible online.

His whole book is a huge compendium of statistical material on the inequalities of wealth and fortunes and this rising inequality is the big issue for him and the main reason for economic and social crisis. He points out, for example, that in the USA, 5 percent of households own a majority of the wealth while the bottom 40 percent have negative wealth because of indebtedness. American income tax data too shows a monstrous concentration of wealth, not just in the hands of the top 1 per cent, but in the top 0.1, or even 0.01 percent. Moreover, he explains, this trend of increasing concentration of wealth is bound to continue.

In so far as Piketty bases his ideas on an economic theory, he bemoans the fact that money makes money. He has no objection to what he calls ‘entrepreneurs’ making a killing, but the fundamental flaw he sees in the system lies in the fact that once wealth has been established – by the self-same dynamic and enterprising entrepreneurs – it then continues to accumulate, even beyond the point when the initial dynamism has faded. He notes ruefully the fact that so many of the world’s billionaires are no more than rentiers, making more money from money. Citing Bill Gates as an example, he makes the point that Gates’s $50bn wealth “has incidentally continued to grow just as rapidly since he stopped working”. It is as if Piketty wants capitalism, but without the natural laws of capitalism. It is like asking the Devil to renounce sin.

The fear of class struggle

In passing, Piketty also has a pop at the ludicrously inflated salaries thrown around in the boardrooms of big companies and this, together with his highlighting the data on inequality, exposes the real rationale behind the book and the reason for its popularity even among capitalism economists. The problem is that they are all concerned about the threat of class struggle as a result of the depression in living standards faced by most people.

Like all capitalist economists and political commentators, Piketty fears for the future. He sees the possibility that what he calls ‘democracy’ may be undermined by the unchecked growth of rentier wealth, what he calls “patrimonial capitalism”. Not that he offers any realistic solutions. The best he can come up with is a tax on the wealth of the non-entrepeneurial billionaire class. Better still if this wealth tax is coordinated across the globe. It doesn’t need a Marxist to point out the flaw in this argument because even Piketty himself says this policy – the only one he advances – is “utopian”.

Piketty’s book has put the spotlight on important aspects of the workings of capitalism. It exposes the way the twenty-first century global economy is owned and managed by an extremely tiny kleptocracy which has no confidence and no hope for the future. The policy of Marxists is for a different form of economic management, one based on a democratic plan of production, using all the science, technology, skills and resources of the planet for the advancement of all humanity.

Piketty reminds us of the world perspective of the capitalist class – unending concentration of wealth and an unbroken march to greater and greater social upheaval. The role of Marxists is not to try to avoid this scenario – it is not something of our making in the first place – but to prepare for it in advance and argue for the revolutionary transformation of society as the only genuine alternative for the whole of humanity.