Today is the 200th anniversary of what has gone down in history as the Peterloo Massacre. This is one date that the ruling class has little desire to remember. Even now, two centuries on, a reminder of the bloodshed and violence associated with the history of British capitalism will be uncomfortable for the establishment.

“The established school of history” (as historian E.P. Thompson called it) has always sought to belittle what happened on 16 August 1819. They describe Peterloo as being just a minor accident; a mishap at worst. For example, Dominic Sandbrook, writing in the Daily Mail, happily describes this “accident” as being “no big deal”; “barely a massacre at all”.

For workers today, however, this event remains important – not least because it shows the real, ugly face of capital: ruthless and brutal. Peterloo is part of our history – the real history – and should not be forgotten.

Dark Satanic Mills

The Industrial Revolution – which occurred between the middle of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century – represented one of the fastest and most violent transformations of society ever seen. Countries like Britain had been heavily industrialised within a process of decades, ripping apart traditions, customs, and institutions that had endured for centuries.

Marx and Engels summed up this rapid development of capitalism as follows in 1848, writing in the Communist Manifesto:

“Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones…

“The bourgeoisie has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam navigation, railways…clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground…”

Manchester was at the heart of this process in England. Such was the transformation of the city into an industrial hothouse that its population rose from 41,000 in 1774 to over 200,000 by 1816.

Just a few decades later, whilst working in his father’s business in the city, Friedrich Engels used Manchester as a case study for his book on The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844). Elsewhere, Sir Charles Napier said of the city: “Manchester is the chimney of the world…The entrance to hell realised!” (Quoted in The Peterloo Massacre, Robert Reid 1989)

Huge profits were being generated for the capitalists. But the working masses, torn from their farms and villages to work in the huge factories that soon dominated the Manchester skyline, saw little of this. Hours were long and hard. Protections for the workforce were non-existent.

The introduction of steam-driven machinery – not least in the massive weaving factories – meant that equipment could be operated not only by men, but also by women – and even children. Needless to say, these layers were paid less and exploited more. As a result, the struggles of 1819 saw the growing involvement of women, politicised by the terrible conditions they endured.

Capitalism likes to present itself as progressive. But those who lived through this period could only see the progressive movement of money from the poor to the rich.

Radicalisation and repression

The revolutionary transformation in industry and production at this time, was accompanied by an equally dramatic rise in radicalism and protest.

The capitalist class, having grabbed the state machinery from their feudal predecessors, was determined to ensure that wealth and power now remained in their greedy hands. Far from establishing new freedoms and rights, they set about imposing new and evermore ruthless laws to maintain and protect the rule of the rich and the ‘rights’ of private property. This included a sharp rise in the number of offences deemed to be punishable by death. Hanging or transportation were common penalties for even minor offences.

The working class began to fight back – first in the countryside, but soon in the towns and cities also. England was closer to revolution than at any point since the Civil War. Revolutionary France was an inspiring example for all to see.

The summer of 1795 saw a collapse of wages in the weaving industry. This quickly resulted in a rise in revolts and rebellions, including disorder in Birmingham and a mutiny of the Oxford militia.

The ruling class were terrified of this angry mood. Officials therefore passed a series of public order acts to make assemblies of 50 or more illegal. More seriously, they declared that anything deemed to be an ‘attack on the constitution’ was a hangable offence.

Despite these repressive measures, there were further economic crises in 1797,1799,1801,1803 and 1808. In the major crisis of 1812, over 12,000 troops were garrisoned to deal with revolts. By the 1830s this number was over 30,000.

The response of the ruling elite was always the same: repression. The Luddite rebellions were typical of this. Hangings and transportations were carried out in vast numbers to break the revolt and send a harsh message to all those who would rebel in the future. At one trial, 17 were sentenced to hanging – including 14 on just one day.

This repression did not only apply to radicals and those attacking the system. Workers organising and fighting for better pay and conditions who also subject to harsh reprisals.

In order to better exploit the masses, the government abolished many of the traditional rights and protections. Some of these dated back to Elizabethan times. The Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, for example, made trade union organisation illegal.

Yet the state encountered great difficulty in enforcing these laws. For example, only seven convictions under the Acts were recorded in Lancashire (excluding Liverpool and Wigan) between 1818 and 1822. One coal merchant and magistrate in Bolton, Mr Fletcher, complained in September 1818:

“About Oldham the colliers are universally out…the masters have not the courage to proceed against them for combination or neglect – although the workmen’s committee sits on stated days at a public house in Manchester as if on legal business.” (quoted in Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution. John Foster, 1974)

‘Old Corruption’

Still, conditions only got worse. The end of the Napoleonic Wars had thrown 300,000 men back onto the labour market, at a time when the economy was suffering from falling trade and the loss of lucrative wartime contracts. By 1816, for example, Britain’s export levels had fallen to 66 percent of what they had been just two years earlier.

Unemployment and under-employment rose – at a time when there was little-to-no social support or benefits. A sharp rise in the price of bread also piled on the agony for the masses. Workers came to realise that the government simply couldn’t care less and were not going to take any remedial action whatsoever. Instead, as the anger from below grew, the ruling class increasingly looked upon the masses with fear.

Governments of this period reflected the interests of “Old Corruption”: the landed gentry; wealthy merchants; and newly-enriched capitalists. They were reactionary to the core.

The establishment was convinced that revolution was looming and that all their privileges, amassed over the centuries, were under threat. “I am sorry to say that what I have seen and heard today convinces me that the country is ripe for rebellion,” wrote one Bury magistrate in a panic in 1801 after witnessing a rally. “A revolution will be the consequence.” Such fears were reflected at the highest levels – not least in the government.

The administration that presided over the Peterloo Massacre was typical of its time. The Tory government in 1819 was headed by PM Lord Liverpool – the “Arch Mediocrity” as Disraeli called him.

The key figure, however, was the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth. It was Sidmouth who manoeuvred to suppress revolt and dissent using all available means. Writing about this government, historian Robert Reid later noted that:

“[The attitude] these men held towards home affairs was that the art of good government lay solely in the maintenance of discipline. The law of the land existed for few purposes other than the control by punishment of the working classes.”

In 1817, the Blanketeers set out to walk from Manchester to London with a petition demanding parliamentary reform. Despite being suppressed, this march fuelled the fears of the government, who saw revolution everywhere.

The throwing of a potato at the coach of the unpopular Prince Regent provided further excuse for even more repressive measures to be rushed through parliament, under the urgings of Sidmouth. These included the suspension of Habeas Corpus and the passing of the Seditious Meetings Act. According to Robert Reid, England came “closer in spirit to that of the early years of the Third Reich that at any other time in history”.

Rotten boroughs

As a result, protests took on an increasingly political edge. Central to this was the growing demand for parliamentary reform. The ‘rotten boroughs’ system meant that old rural areas returned the bulk of MPs to parliament. These ‘representatives’ were often elected by just a handful of trusted cronies. The new industrial conurbations (including Manchester), by contrast, elected nobody. As a result, demands for equal representation, and for the enfranchisement of all men (though not women, at this time) began to take root.

The government was having none of this, however. Lord Sidmouth therefore set about increasing the army of spies around the country to uncover and snuff out any evidence of dissent.

In Manchester, behind the government and its forces, lurked the local magistrates: wealthy and corrupt businessmen who ruled the city with an iron fist.

“As well as dominating Manchester’s ramshackle institutions of local government they associated in a secretive network of orange and masonic lodges,” noted Robert Poole. “Some had a high-Tory and even Jacobite political background that encouraged them to see themselves as an inner governing elite responsible to no-one.”(Manchester Region History Review, Vol. 23, 2014).

These gentlemen even had enough funds to run their own network of spies on top of the ones employed by the national government. They would play a key – and bloody – role in what happened at Peterloo.

Military power in the Lancashire region lay under the command of Sir John Byng. In 1817, Byng suppressed a rally at St Peter’s Field – the eventual site of the Peterloo Massacre – with considerable efficiency. However, with a limited number of troops in England, the raising of citizens’ regiments – the yeomanry – became a priority for Sidmouth. These would be under the control of the local authorities, i.e. the magistrates.

Authorities alarmed

Although a weavers’ strike had been harshly repressed, and conflict on the industrial plain seemed to have abated, the political unrest continued to rise during 1819. Both Sidmouth in Westminster and the local magistrates in Manchester viewed this with alarm, pressing their spies for information.

Although a weavers’ strike had been harshly repressed, and conflict on the industrial plain seemed to have abated, the political unrest continued to rise during 1819. Both Sidmouth in Westminster and the local magistrates in Manchester viewed this with alarm, pressing their spies for information.

So it was that a mass meeting to demand political reform was announced for the start of August 1819. The magistrates quickly declared this to be illegal. However, their declaration was badly drafted and seemed to imply the opposite, saying: “We…do hereby Caution all persons to abstain AT THEIR PERIL from attending such an illegal meeting.”

Oddly enough, Sidmouth now urged caution over dealing with any such meetings. He was a stickler for procedure, noting the problems arising from the botched legal notice. However, he was also ill for most of that summer, and so it was left to his ruthless underlings to act in his name.

In any case, the magistrates knew that they could “rely on Parliament for an indemnity”, as Sidmouth had privately hinted earlier. The state was more than happy to let the local authorities do their dirty work for them, and maybe take the blame. And the magistrates were more than happy to oblige.

Since the first meeting was banned, the organisers set about announcing an even larger one. This was set to take place on 16 August, with Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt as the main speaker. With such a draw, a huge attendance was expected.

Although Hunt was keen to avoid the threat of violence, trying to placate the local authorities, others were taking steps to ensure that they would be ready to defend themselves. After the event, much mention was made by state spies of the drilling and marching taking place in the fields around Manchester. Nevertheless, the organisers made it clear: no weapons were to be carried on the day.

As hysterical reports flowed into the hands of the local and national authorities, calls were issued for firm action to be taken against the ‘insurrectionary’ rally. The Magistrates fuelled the fears of violence, mobilising both the Cheshire and Manchester yeomanry. Sir John Byng was alerted, as commander of the military forces, and told to take any action deemed necessary.

On the day itself, however, Sir John Byng was not in Manchester, but at York for the August races. He was eager not to miss this high point of the social calendar, and he informed the authorities of as much. The magistrates, aware of Byng’s complaints, wrote him a letter excusing him from having to travel back.

Matters were duly left in the hands of Lt. Col L’Estrange. All the various forces were under his control bar one: the Manchester yeomanry cavalry, which was under the immediate command of the local magistrates. So too were a force of around 400-500 special constables – i.e. hired thugs in uniform.

On the morning of the 16th, thousands streamed into the centre of Manchester from the various parts of the city and beyond to attend the great meeting. They came by foot (there was no public transport, of course), often starting off early in the morning to arrive in time for the speakers. Bosses arrived at their factories to find them deserted. This was a mass strike in all but name.

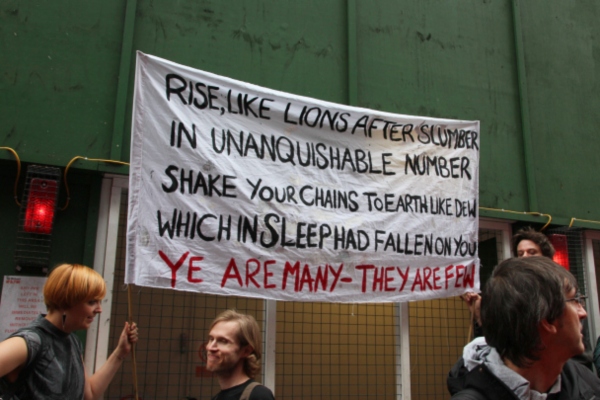

Banners with slogans such as ‘Liberty and fraternity’, ‘Annual Parliaments and Universal Suffrage’, and ‘Union is strength – Unite and be free’ were commonplace as the people marched through the streets towards St. Peter’s Field. Again, the large contingent of women on the various marches should be noted.

By lunchtime, the square at St Peter’s Field was hot and packed, with between 50,000 and 60,000 waiting for the meeting to begin. The magistrates, overlooking the crowd, hollered for action. The yeomanry – many already drunk – were itching to advance. All that was needed was for the legal formalities to be concluded.

Carnage and chaos

The Riot Act was speedily read, in accordance with the law. But no one could actually hear it. The Act was passed in 1715 after a spate of disturbances. It had the advantage for the state that, once read, it upgraded the offence from a misdemeanour to a felony. And it ensured that the local authorities were now protected from any legal fallout.

The Riot Act was speedily read, in accordance with the law. But no one could actually hear it. The Act was passed in 1715 after a spate of disturbances. It had the advantage for the state that, once read, it upgraded the offence from a misdemeanour to a felony. And it ensured that the local authorities were now protected from any legal fallout.

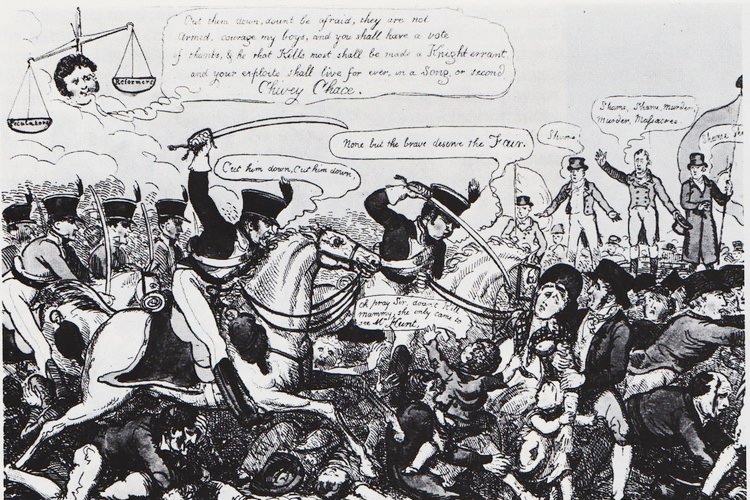

Hunt had arrived at about 1.00pm to loud cheers. He was in full flow when the Manchester yeomanry moved towards the crowd at 1.40pm, intending to arrest the organisers. Sabres drawn, they plowed into the people.

L’Estrange, meanwhile, was leading his forces around the back streets, but was still too far away to take command of those already in the square. Ironically, when the special constables raised their truncheons to identify themselves to the yeomanry, they were attacked as well.

Two years earlier, Byng’s forces had broken up a rally in the same square using the flats of their swords. But this time the Yeomanry just hacked and stabbed indiscriminately. When L’Estrange finally arrived a few minutes later, the situation was already out of control. Some of the Hussars began trying to restrain the yeomanry, but with little success. In fact, given the cramped and chaotic conditions, their forces only added to the violence inflicted on the people as horses and men crashed into each other.

In any case, L’Estrange saw his duty as protecting those yeomanry who were encountering resistance from the crowd, and completing the ordered dispersal at whatever cost. The Manchester Guardian later wrote that “the carnage seemed to be indiscriminate”.

And so it was. By the time the violence ended and the area had been cleared (at about 2.00pm), at least 650 men, women and children had been injured. 18 were dead or dying, including four women and one young child.

The Yeomanry still sought revenge against those protestors who resisted their attacks, as did the local people in turn against them. Riots continued in some outlying towns into the next day, as the marchers expressed their anger at what had happened.

The legacy of Peterloo

Some of the press who were present faithfully reported on what they had seen. They quickly coined the phrase ‘Peterloo’, providing an ironic comparison to the recent conflict at Waterloo.

Some of the press who were present faithfully reported on what they had seen. They quickly coined the phrase ‘Peterloo’, providing an ironic comparison to the recent conflict at Waterloo.

Any hope of justice for those killed or injured by the mad violence of the authorities would soon be shattered. Those arrested were subjected to the full force of the law, although many were later released without publicity.

No one was ever made to pay for what had happened, despite several attempts to seek justice. The government, far from realising that they had gone too far, congratulated themselves over the firm response in ‘dealing’ with the threat to their positions and power. In fact, they moved to round up any radicals they could lay their hands on, imposing yet more repressive laws to curtail the anger of the people.

The spirit of the working classes was not broken, however. Indeed, in the previous year, Manchester workers from 14 different trades had met to form the General Union of Trades. This trade unionism continued to develop. And by 1824, the state felt it necessary to repeal the Combinations Acts, rather than risk further opposition – although they quickly drew up new repressive laws to take their place. The old ‘rotten boroughs’ were also reformed, mainly to provide seats in parliament for the industrial capitalist class, but also to hold off the continuing pressure from below.

The people would not stay quiet. Within a few years, the countryside erupted with the ‘Captain Swing’ revolts. And the political struggle began to coalesce into the Chartist movement.

In Manchester today – and throughout this weekend – trade unionists, socialists and activists are gathering to mark Peterloo’s 200th anniversary. On this occasion, we should note that the struggle that led to so much bloodshed on this date in 1819 has not been settled. We are the descendents of those who marched to St. Peter’s Field – just as today’s bosses and their political representatives are the reincarnations of the likes of Sidmouth and Lord Liverpool.

The class struggles of Peterloo and the Chartists are part of our history. It is vital that we remember these events, as we continue the fight for workers’ rights – and above all for socialism.