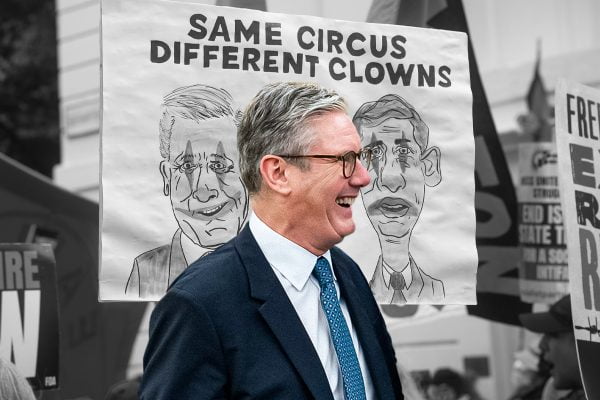

Starmer’s Labour are in power, but unloved. From the almost-record low election turnout, to the reduction in the party’s overall number of votes: there are plenty of indications that this Labour government has been deeply unpopular from birth.

Now, following a turbulent first month in office, including backbench rebellions and far–right riots, it is clear that Starmer’s honeymoon period is over. Recent opinion polls indicate that the Labour leader’s approval ratings have already dropped substantially since he gained the keys to Number 10.

Another warning sign for Starmer – and the ruling class that stands behind him – is the large number of protest votes registered against Labour on 4 July. This resulted in four Green representatives and five independent MPs being elected to Parliament.

They were soon joined on the opposition benches by seven ex-Labour MPs, scandalously suspended by Sir Kid Starver for their defiant stance over child poverty.

They were soon joined on the opposition benches by seven ex-Labour MPs, scandalously suspended by Sir Kid Starver for their defiant stance over child poverty.

This array of left-of-Labour MPs in the House of Commons has once again prompted serious suggestions about the creation of a new political formation, as an alternative to Starmer’s big business party.

But before socialists embark on such a venture, it is vital that we fully absorb and digest the lessons provided by previous left efforts.

After all, as the saying goes: those who do not learn from history, are doomed to repeat it.

Palestine candidates

Earlier this year, following his by–election victory in Rochdale, George Galloway called on Jeremy Corbyn to lead an “alliance of remaining socialists”.

The Workers’ Party leader recently reiterated this suggestion, saying that “Corbyn must be our Mélenchon” and “unite all forces behind him in a Popular Front” – a reference to French leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his ‘New Popular Front’ (NPF): a loose coalition that recently topped the country’s legislative elections, keeping Le Pen and the right wing out of power.

Mr Corbyn must be our #Melanchon He is the best leader to unite all forces behind him in a Popular Front. We in the @WorkersPartyGB and our 210,000 voters will follow him. @jeremycorbyn

— George Galloway (@georgegalloway) July 7, 2024

Similarly, in the run-up to the general election, Guardian journalist Owen Jones launched the ‘We Deserve Better’ initiative, in an effort to see Green and independent candidates take seats off Labour. The campaign now hopes to build on recent successes in future elections.

Just last week, meanwhile, news reports suggested that Corbyn is in talks to form a new official parliamentary group, in order to boost the influence of independent MPs in the House of Commons.

At the same time, there have been calls for the ‘suspended seven’ – including John McDonnell, Apsana Begum, Zarah Sultana, and Richard Burgon – to fully break with Starmer’s party, and to help in the birthing of a new political grouping.

Pro-Palestine supporters, in particular, would certainly have much to gain from such an electoral formation.

Independent candidates gave Labour a bloody nose in five areas, primarily by mobilising voters over the question of Gaza.

But many others came a close second: Leanne Mohamad in Ilford North, who lost to arch-Blairite Wes Streeting by just 528 votes; Ajmal Masroor in Bethnal Green & Stepney, who narrowly lost to Labour MP and genocide-backer Rushnara Ali; and Workers’ Party candidates in Birmingham’s Yardley and Hodge Hill constituencies, who were challenging Labour right-wingers Jess Phillips and Liam Byrne, respectively – to name just a few.

And in all of these cases, and more, these pro-Palestine candidates would have won, had the Greens – nominally in favour stopping Israel’s war on Gaza, and ending the UK arms sales that fuel this – encouraged voters to back these better-placed alternatives.

There is therefore a clear pressure for those to the left of Labour to coordinate efforts at future elections.

“New movement”

Amongst those tentatively raising the proposal for a new electoral option is Jeremy Corbyn himself – probably the most high-profile of these recently-elected independents.

In the end, thanks to a powerful grassroots campaign, the former Labour leader comfortably retained his Islington North seat, securing almost half the vote in the constituency.

Since then, Corbyn has alluded to the idea of maintaining the momentum of his campaign – not only locally, but even nationally.

In an article in The Guardian last month, Corbyn outlined his plans to establish a ‘People’s Forum’ in the north London constituency: “a shared, democratic space for local campaigns, trade unions, tenants’ unions, debtors’ unions, and national movements to organise, together, for the kind of world we want to live in.”

This template could be replicated across the country, Corbyn suggests, in order to channel the “discontent with a broken political system” that expressed itself in this general election as “a rejection of the political establishment”.

“That’s why our campaign will organise with those who have been inspired by our victory to build community power in every corner of the country,” the left-wing MP continues. “Once our grassroots model has been replicated elsewhere, this can be the genesis of a new movement capable of challenging the stale two-party system.”

Although the wording is vague, the intentions are clear: to bring together all the anti-Labour anger under a single umbrella; to build a social and political “movement” that, as Corbyn explicitly states, “will eventually run in elections”.

Our victory is the beginning of a movement that can win all over the country.

Be part of it at https://t.co/6c0bPmge2V pic.twitter.com/sZZDXDzCjX

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) July 12, 2024

Form and content

Perhaps burnt by his own previous experiences as Labour leader, in his recent article, Corbyn warns against creating a “new, centralised party, based around the personality of one person”.

Instead, he refers only to building a “movement”: to offer a “real alternative to child poverty, inequality and endless war”; and to provide a “real opposition to the far right”.

The organisational form of any new electoral force is a secondary question, however. Whether it comes in the shape of a party or a “movement”, the most decisive factor in determining the outcome of any offering is its political content: its programme, approach, and outlook.

Only by basing any new political movement on clear socialist policies, militant methods, and a perspective of class struggle – not class collaboration or compromise – can Corbyn and the left ensure its growth, strength, and success.

Lessons of Corbynism

This is the valuable – and vital – lesson provided by round one of Corbynism.

This is the valuable – and vital – lesson provided by round one of Corbynism.

Inspired by the prospect of an alternative to both the Tories and New Labour, hundreds of thousands rallied behind Jeremy Corbyn to help him win the Labour leadership contest in 2015 – and then again in 2016.

From day one, the Labour right wing – acting on behalf of, and with the full support of, the establishment – conspired to remove Corbyn and his allies. And all manner of evidence has emerged retrospectively to prove this fact.

Unfortunately, instead of mobilising his army of supporters to drive out these Blairite backstabbers and saboteurs, Corbyn and his advisers constantly sought to appease them.

The left leaders offered endless olive branches: including political enemies in the shadow cabinet, and refusing to bring in mandatory reselection (the democratic, open selection of MPs). They constantly sought to compromise with their rabid opponents, bending over backwards and apologising for baseless antisemitism smears. And they appealed for ‘unity’, with calls for their critics to respect the party as a ‘broad church’.

This confusion and softness gave right-wingers the upper hand. Unlike the left, they showed no mercy. They ruthlessly went on the offensive, witch-hunting socialists and purging the left. And without any real fightback from the top, this retreat turned into a rout.

Eventually, in 2019, without any explanation for why the party had suffered a bruising election defeat, Corbyn fell on his sword and resigned as Labour leader. Keir Starmer manipulated and deceived his way into position. And the left was cowed into submission, with Corbyn and others bureaucratically blocked and deselected as candidates, one by one.

True, had Corbyn confronted the party’s right wing, which dominated the Parliamentary Labour Party, this could have split the party, leaving the left with a minority of MPs. But even then, the vast majority of the ranks would have remained loyal to Corbyn, taking with them control of hundreds of constituency parties.

In the end, the ‘clever’, timid tactics pursued by the left leaders produced the worst possible result: thousands of socialists expelled, without an organisation; tens of thousands more leaving in disgust, demoralised and burnt out; and, more recently, dozens of uncoordinated attempts to stand independent candidates, now joined by a handful of exiled left MPs.

Programme and policies

Corbyn’s recent win in Islington North, combined with the drop in the overall Labour vote between the last election and this one, is a reminder that the problem was never that Corbyn was ‘unelectable’.

Corbyn’s recent win in Islington North, combined with the drop in the overall Labour vote between the last election and this one, is a reminder that the problem was never that Corbyn was ‘unelectable’.

Rather, the issue lay with the left leaders’ attempts to maintain unity with those who were fundamentally hostile to their socialist aims and ambitions.

By contrast, a party unified on a principled political basis, fighting for bold socialist policies, and basing itself on the mass mobilisation and organisation of radicalised workers and youth, would have been unstoppable.

That is what the left should be looking to build today, rather than a politically amorphous, structureless, muddled ‘movement’.

A mass party will not emerge fully-formed from the outset, however. The perfect programme does not fall from the sky, but can only be constructed through practical experience and activity – and clarified by open discussion and honest debate – by putting different ideas and tendencies to the test.

Yet the leaders of the Corbyn movement refused to countenance any serious struggle for their demands, instead believing that these could be obtained by appealing to the capitalists and their agents to be ‘nicer’ and ‘kinder’.

And this utopian perspective ultimately was their undoing, leading them to demobilise activists at every juncture, on the one side, whilst making concessions to those who sought to crush them, on the other.

Oxygen of democracy

This highlights a final lesson from the experiences of Corbynism Mk1: the danger of restricting or repressing democratic discussion and decision-making.

To maintain its health and vitality, any real living movement or organisation must be suffused with the oxygen of genuine, collective democracy.

Furthermore, it must not limit itself to the parliamentary plane, but must draw upon the strength of the organised working class, by utilising fighting methods of mobilisation and struggle.

In the case of the original Corbyn movement, the move by the self–appointed leaders of Momentum to suppress the left organisation’s democratic structures marked a major turning point in the struggle.

From then on, grassroots activists were deprived of an important means through which to organise in defence of Corbyn, and to kick out the right wing. The Blairites, on the other hand, were highly organised, and were thus able to regroup and go on the offensive, putting the left on the backfoot.

Despite this, rank-and-file members took the initiative to organise themselves locally. And on this basis, questions like mandatory reselection and the restoration of Clause 4 (the party’s old commitment to common ownership) made their way onto the agenda at Labour conference – only to be quashed by the trade union leaders.

Nationally, a firewall was erected between Corbyn and the party’s left-wing mass membership, with questions of strategy and programme decided by a small bureaucratic clique.

These conservative ladies and gentlemen were afraid of allowing the movement to get out of their control – lest activists rock the boat by taking the fight to the right.

Ultimately, their woolly reformist outlook led them to naively believe that ‘unity’ with the right wing really was possible; that the left, representing the interests of the working class, could coexist with the right, representing the interests of the ruling class.

Related to this was the left leaders’ belief that the progressive policies in Corbyn’s programme – including nationalisation, scrapping the anti-union laws, and tackling the climate crisis – could be implemented within the limits of capitalism, by ‘taxing the rich’.

Unfortunately, this remains the stance and attitude of the left reformists today, who continue to base their entire strategy on vain appeals to the ruling class for crumbs and calm – whether it be on the question of war, democratic rights, or workers’ pay.

Enough is Enough

These same errors were later repeated by the founders of the ‘Enough is Enough’ (EiE) campaign.

Founded on the back of a wave of militant industrial action, and linking this tsunami of strikes to a programme of left demands, EiE was able to organise mass rallies and demos across the country.

Had this been given an organised expression, with democratic groups and structures established at a grassroots level, EiE could have laid the foundations for a powerful new political movement.

In the end, however, without any perspective or strategy, all this potential was squandered by the EiE leaders. Within a few months, this promising fledgling movement – with all its energy and enthusiasm – had completely dissipated.

The experiences of EiE and Momentum tragically demonstrate how weak politics combined with loose, nebulous ‘movements’ are a recipe for impotence and paralysis.

This should be a warning for those seeking to create a similar ‘movement’ today, based on these lacklustre blueprints.

Revolutionary leadership

The barbaric far–right flare up seen on Britain’s streets this month highlights the dangers if the left fails to provide a genuine socialist alternative to the rotten establishment and capitalism’s broken status quo.

The barbaric far–right flare up seen on Britain’s streets this month highlights the dangers if the left fails to provide a genuine socialist alternative to the rotten establishment and capitalism’s broken status quo.

If efforts to form a new political force to the left of Labour are to be successful, however, it is vital that those leading such an initiative learn from the lessons outlined above.

It is still early days. Keir Starmer only moved into Downing Street a few weeks ago. And the real opposition to his big business government will be forged on the basis of events, as workers begin to move into action against the attacks and austerity that lie in store.

We cannot say yet what will emerge to temporarily fill the vacuum on the left. We don’t have a crystal ball. There are many as-yet-unknown variables that will determine the answer to this equation. The outcome will ultimately be determined by a struggle of living forces. And the question of leadership, above all, will be key.

What we can say for certain, however, is that whatever political developments or new formations arise, we – the revolutionary communists of the RCP – will strive to be the most determined, audacious, and far-sighted element in the situation: offering a clear Marxist perspective; raising bold class demands; and providing a strong backbone to the left and the labour movement.

In this process, through a combination of patient explanation and practical activity, we will fight for our ideas to be the guiding light of any genuine political movement – that is, for the revolutionary party to be the leadership of the working class, waging a militant struggle to overthrow capitalism internationally, and establish worldwide workers’ power.

This is what is required. This is our aim. This is the task of communists at this historic juncture.

So don’t wait or hesitate. Join the RCP today, and help build the revolutionary alternative that the working class needs and deserves.