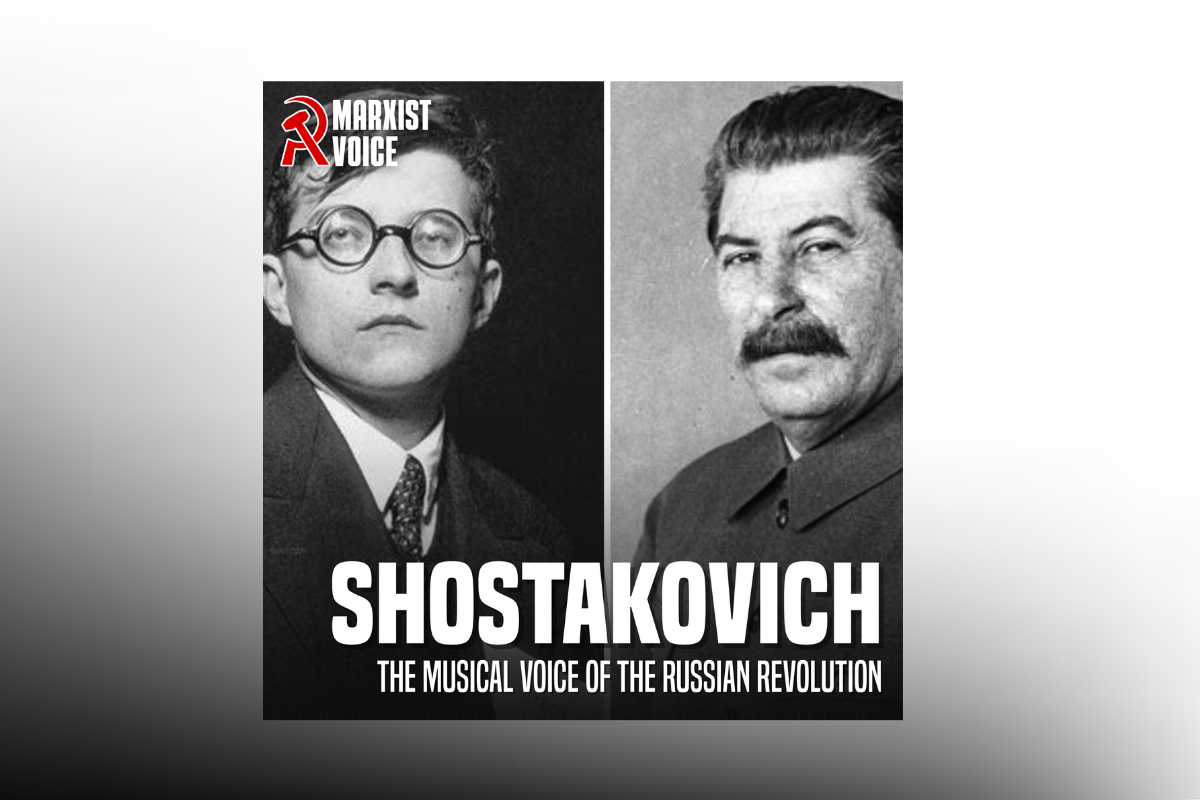

David Lynch, who died on 15 January 2025 at the age of 78, made surreal, deeply unsettling films and television shows, including Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and many others.

His works were mysterious, even inscrutable at times, and used dreamlike imagery to explore the alienated state of American society.

Despite the eccentricity of much of his output, he enjoyed considerable success and amassed a legendary reputation as a singular artist with the unique ability to capture the absurdity of everyday life under capitalism.

It is hard to imagine we will have another artist as uncompromising and militantly opposed to the corrosive effect of the market over art as David Lynch; or at least one doing so to the same level of commercial and critical acclaim.

He and his work epitomise art as something that must be free, something that must operate on its own terms and not be subordinated to any financial or even political goal.

Lynch actually denied he was a “political person”, and his personal political persuasions were as elusive as his artistic intentions. And yet his films were never ‘art for art’s sake’, they had strong messages about society and its problems, reflecting the extremely earnest character of the man himself.

For a man who was notoriously tight-lipped about his artwork, he was very explicit about his disgust at the role of business in filmmaking. In a 2017 interview, he said:

“If you’re thinking about making money, then it’s another whole thing. Then it doesn’t matter if you don’t get final cut, you’re gonna get your money, and if that’s the only thing you’re interested in, then I wouldn’t even want to talk to [you]”.

He seems to have been radicalised by the decadence, crudeness, and, as he would have seen it, literal evil of capitalist society as it hurtled blindly forwards.

In one sense, he was politically conservative, yearning for the simpler, more optimistic times of the 1950s. “When I picture Boise [the town he grew up in in the 1950s] in my mind, I see euphoric 1950s chrome optimism… I love the 50s. There’s a kind of a purity and a power.”

However, he clearly understood that, even in this seemingly idyllic post-war period of apparent boom, innocence and prosperity, dark forces were at work, and the dreamy optimism was to a large extent just that: a dream that people were lulled into.

Mulholland Drive

The work that best encapsulates his ideas and techniques is probably the 2001 film Mulholland Drive, often regarded as Lynch’s masterpiece.

Set in Hollywood, it is about a young woman’s dream of becoming a movie star: so far, so familiar. Beyond its basic starting point, however, the film rapidly takes on an extremely surreal and mysterious character, to the extent that many viewers find it incomprehensible, tying themselves in knots as they try to solve its riddles.

Like the rest of Lynch’s work, it is clearly a highly symbolic film. But there seem to be so many layers to the symbolism, which is at times extremely strange and disturbing. So many of the ‘clues’ of the film’s meaning appear to be red herrings, that for some it is an unsolvable mystery, or even a load of pretentious rubbish.

Lynch himself refused to explain his films.

He did once shed some light on why they seem so hard to understand, however: “I don’t think that people accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense. I think it makes people terribly uncomfortable.”

In other words, the mysteriousness of his films is the whole point. His work is meant to symbolise the unfathomableness, as he saw it, of life, and directly confront the viewer with the alienation at its core.

In the Marxist sense, alienation refers to man being confronted with the product of his labour, but seeing none of himself reflected in it. For Lynch, human civilisation itself had become alien, strange and out of our control.

When you watch his films with this understanding, they start to make sense.

Regarding Mulholland Drive’s protagonist, our would-be movie star (played by Naomi Watts), Lynch said that “This particular girl—Diane—sees things she wants, but she just can’t get them. It’s all there—the party—but she’s not invited. And it gets to her.

“You could call it fate—if it doesn’t smile on you, there’s nothing you can do. You can have the greatest talent and the greatest ideas, but if that door doesn’t open, you’re fresh out of luck.”

The film starts out following her seemingly promising attempts to ‘get invited to the party’, i.e. become a movie star. But this is all shown in such a sickly-sweet light, so idealised and dream-like, that it is impossible not to feel that it is too good to be true.

Even if one does not understand exactly what is happening, something is clearly amiss.

Alongside this process, we are shown a director (played by Justin Theroux) attempting to cast the actor he wants for his new movie, but coming up against extremely sinister studio executives in dark rooms insisting he cast ‘the girl’ that they want.

This director quickly seems to become the victim of a Hollywood conspiracy. After he loses all of his money, he is forced to meet a bizarre ‘cowboy’ in the middle of the night, who forcefully tells him he must cast ‘the girl’.

The director is ensnared by the evil forces of money, which denies him the ‘final cut’ that, as we have seen, was so important to Lynch.

The exact meaning of these creepy events and their relation to Diane is very hard to discern. But the overall effect clearly juxtaposes the dream of Hollywood success with the sordid reality of rich, powerful men manipulating these dreams for their own gain.

Lynch’s depiction of Diane’s struggle to get ‘invited to the party’, and his comments about the mysterious forces that determine our fortunes (‘call it fate – if it doesn’t smile on you, there’s nothing you can do’), combined with the sinister machinations in the Hollywood studio, make it pretty clear what his message is, even if the precise plot details are confusing.

Alienation

Mulholland Drive, along with much of Lynch’s work, is about alienation, about the contradiction between our collective dreams on the one side, and the dark and cruel reality on the other.

Quite why Diane doesn’t achieve her Hollywood dream, or why these studio executives are fixated on a different ‘girl’, and what the connection between these aspects of the story is, is hard to fathom (though there are clues aplenty).

But is life in the anarchy of the capitalist market not like that? Is it not inscrutable and even meaningless as to why this or that person finds success, sometimes incredible success, and others face crushing failure and poverty?

And doesn’t this irrationality, and our own impotence in the face of it, doom so many to wallow in anxiety and other deep psychological problems, constantly confused and looking for someone to blame?

Do our personalities not often fracture between dreams and fantasies, on the one side, and depression and fear on the other?

David Lynch is sometimes described as a postmodern film maker.

It is true that he made films in the same era that postmodernism dominated culture and philosophy, and his work definitely refers to similar questions tackled by postmodernists: loss of identity and meaning, mental illness and confusion, and the sense of a facade of meaning behind which there might be nothing.

There is, however, a profound difference.

Postmodernist philosophers generally celebrated the cynical atmosphere of bourgeois society in the late 20th Century (especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall) and declared all truth, meaning and reality to have somehow disappeared.

For them, all is subjective, reality is ‘created’ by different narratives. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, and films such as American Psycho and Fight Club, are perhaps the best expressions of this outlook in cinema.

David Lynch clearly abhorred this cynical epoch and saw it as provoking deep psychological problems. Not only that, but his philosophy was much closer to that of Objective Idealism than the Subjective Idealism of the postmodernists.

That is to say, he thought there is such a thing as truth, but it originates outside of the material world. He was pretty clear about this:

“I think that ideas exist outside of ourselves. I think somewhere, we’re all connected off in some very abstract land. But somewhere between there and here ideas exist.”

At one point in his TV show Twin Peaks, there is a prophetic ‘Log Lady’ character, who cradles a hunk of wood that speaks strange truths to her.

At one point she speaks directly to the audience, and says: “There are things in life that exist, and yet our eyes cannot see them”.

Although his films are deeply mysterious, they are not at all meaningless facades, they are full of clues to the answers, but Lynch wanted the audience to be the detective working it out for themselves.

For Lynch, abstractions or ideas seem to be forces that struggle with one another, and the result is the events that make up our lives.

One of the things that makes his films so powerful was his knack for tapping into the collective dreams, images, and the ideals of society. He depicted them so forcefully and with such emotional resonance because of this ability of his to grasp these ideas in their pure form.

In Mulholland Drive, the archetypes of the Hollywood Dream are conveyed extremely powerfully through the saccharine dialogue, classic images of Hollywood mansions and the tropes of auditioning.

Lynch was a master of using music and sound design to drench all these idealised images in atmosphere. He worked with his friend Angelo Badalamenti throughout most of his career to devastating effect.

Dreams and nightmares

As we all know, dreams have a dark side.

Mulholland Drive is often described as a nightmare, and it is certainly filled with nightmarish images and sounds. The lighter side of his films was always a little too bright; drenched in a sort of cloying nostalgia, hinting at something uncanny and unsettling about the dreamy positivity.

And alongside this, Lynch would juxtapose truly horrifying stuff: sugary 1950s pop music cutting out to silence or eerie drone noises; scenes of suburban idyll torn apart by sudden terrifying images of strange people, and extreme violence and sexual abuse.

True to his objective idealism, Lynch would manifest dark ideas as real people or monsters haunting the main characters.

In Mulholland Drive, the darkness that is under the surface of Hollywood appears as a literal, disheveled and filthy homeless man looming in a back alley. The sinister Hollywood conspiracy preventing the director from choosing his actors seems to be manifested as the mysterious ‘Cowboy’, who threatens the director.

In Twin Peaks, the equally mysterious character of ‘Killer Bob’, a brutal, otherworldly, murdering rapist that feeds on misery, seems to embody ‘the evil that men do’, as one character suggests.

In fact, Lynch himself confirmed this, replying to an interviewer that Bob represents evil, and is as such “an abstraction with human form. That’s not a new thing, but it’s what Bob was”.

Bob, somewhat like the homeless man in Mulholland Drive, looks almost cartoonishly evil, with long greasy hair, biker gang clothes and a sinister grin. Characters that seem to represent goodness, however, are usually clean cut and beautiful.

This is not because Lynch literally thinks that good people are all beautiful, and bad people ugly, but because his films deal in archetypes. They are like collective dreams (or nightmares), and so as in a dream, characters are symbolic images of our hopes and fears.

Then again, a recurring theme of his work is beauty and innocence being sullied or corrupted.

In the case of Twin Peaks, the story is kicked off with the murder of the town prom queen Laura Palmer, whose seemingly angelic exterior masks a nightmare of addiction and unspeakable abuse.

In Lynch’s films, even archetypes of goodness often contain hidden darkness.

Whatever his own idealist ideology, the dark subject matter he brought to the fore is very real indeed: the power politics and sexual exploitation within Hollywood is real and bad enough in itself, but also has far wider ramifications for our culture in general.

It also reflects the decadence and hypocrisy of contemporary capitalist society as a whole. The original Twin Peaks series deals with the abuse of girls by the family.

The much more recent third series is about contemporary culture’s addiction to nostalgia, its inability to produce anything really new or truthful, and the resulting desire to recapture past glories instead, something Lynch seems to say is dangerous.

Again, we see the contrarian nature of Lynch’s art, which looks fondly on a simpler past but warns against the seductive power of nostalgia. This complexity and multisidedness is partly what makes Lynch such a compelling artist.

All of the themes dealt with in Lynch’s work are important aspects of society today.

Lynch was of course no Marxist, not necessarily even politically progressive, but the point of art is not to present a worked-out and objectively correct political programme, but to capture the emotional significance of the truth.

David Lynch believed strongly in the power of film. He spoke passionately against watching films in the wrong way (i.e. on phones). He wanted the atmosphere of the whole experience to wash over the audience, to sweep them up in the emotional ride.

His films are certainly not for everyone. They are confusing and at times deeply unsettling. Having said that, an overlooked side of Lynch is his humour – all of his work is filled with hilariously absurd moments that are surely intended to be funny. This levity helps temper the shade.

For those who do ‘get it’, his films are intoxicating and moving.

They are not subtle, far from it, but their melodrama is combined with mystery and depth, something that is all too lacking from so many imitators. Such as in last year’s celebrated The Substance, which is both incredibly unsubtle and also utterly lacking in the mystery that emotionally draws the audience in.

A true original that embodied everything an artist should be, his death is a profound loss to culture.