What word connects one of Lenin’s most famous theoretical works; supermarket cereals and silicon microchips; and a popular household boardgame, developed in the early 20th-century? The clue is in the title: monopoly.

Capitalism is often portrayed as the provider of ‘freedom’ and ‘choice’. But this is a complete myth. From the minute we wake up to the moment we go to sleep, our lives are dominated by monopolies; by giant corporations that control huge chunks of their respective industries.

As consumers, for example, we can ‘choose’ from a dazzling variety of brands when it comes to food and drink. Yet these are all owned by just a handful of major multinationals.

Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Keurig Dr Pepper together account for a staggering 93 percent of fizzy drink sales in the USA. Just one of these firms (Pepsi) controls 88 percent of the dip market, with ownership of five of the most popular snack brands. Three beverage behemoths make up three-quarters of beer sales. And regarding aforementioned cereals, the same number of mega-businesses help fill around 73 percent of breakfast bowls.

In fact, in the case of around 80 percent of everyday grocery items, four or fewer companies have a majority share of the market between them. In turn, these weighty food multinationals, along with retail chains like Walmart and Aldi, dictate the activity of thousands of small, squeezed suppliers below them.

But the power of the monopolies extends well beyond supermarket shelves. At the checkout, for example, most purchases will be made with debit or credit cards provided by just two names: Mastercard and Visa. If you take a flight, you’ll likely sit in a plane produced by one of two aircraft manufacturers: Boeing and Airbus. And in the UK, despite energy regulators’ supposed efforts to promote competition, five private profiteers supply electricity to 70 percent of households.

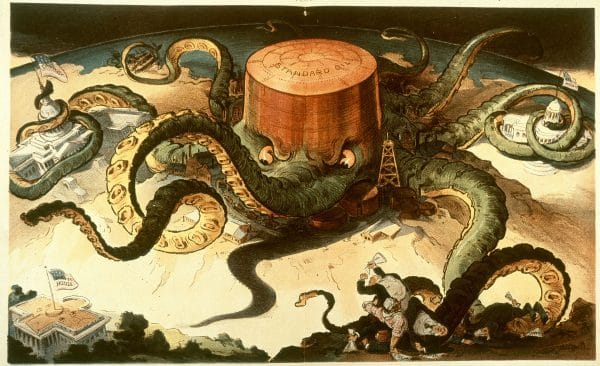

The problem is no less prevalent in the public sector. In Britain, outsourcing leviathans like G4S, Mitie, and Serco have their tentacles in all manner of public services, sucking up billions of taxpayers’ money in the process. The same goes for the construction monopolies. In the US, meanwhile, 86 percent of Pentagon spending goes to just five specialist ‘defence’ contractors.

The grip of the monopolies even extends beyond the grave. Americans who chose to get buried upon meeting their maker have more than a four-in-five (82 percent) chance of being put six feet under in a coffin or casket made by one of two firms.

Corporate concentration

Despite the occasional libertarian assertion that ‘small is beautiful’, it is clear that capitalism means BIG: Big Oil; Big Pharma; Big Tech – and so on. And they keep getting bigger.

Over the decades – in sector after sector, thanks to a series of crises, mergers, and acquisitions – markets have become ever-more concentrated.

In one industry after another, the biggest companies have increased their market share over the last 15 years.

That’s a major reason that income growth has been weak and entrepreneurship has declined. https://t.co/Wcb74fUvzc pic.twitter.com/kh7ojsBDuL

— David Leonhardt (@DLeonhardt) November 26, 2018

One recent academic study, for example, showed that the top firms in the USA have consistently increased their control over America’s economic assets in the past century.

“Since the early 1930s,” state the authors of a paper entitled 100 Years of Corporate Concentration, “the asset shares of the top 1% and top 0.1% corporations have increased by 27 percentage points (from 70% to 97%) and 40 percentage points (from 47% to 88%), respectively.”

The researchers provide evidence that this trend towards greater monopolisation has accelerated since the 1970s. And they find that consolidation has been especially notable in the finance, manufacturing, mining, services, and utility sectors.

Strictly speaking, ‘monopoly’ refers to instances where a single firm holds sway over a certain industry, which is less common. However, in many cases – as with the examples of credit cards, aeroplanes, and coffins – the majority of a given market is now controlled by a ‘duopoly’ of two companies. And ‘oligopoly’, the rule of a small number of powerful corporations (and the oligarchs that own them), is standard in various sectors across the economy.

This is not a new phenomenon, however. For well over a century, capitalism has been characterised by the domination of the monopolies.

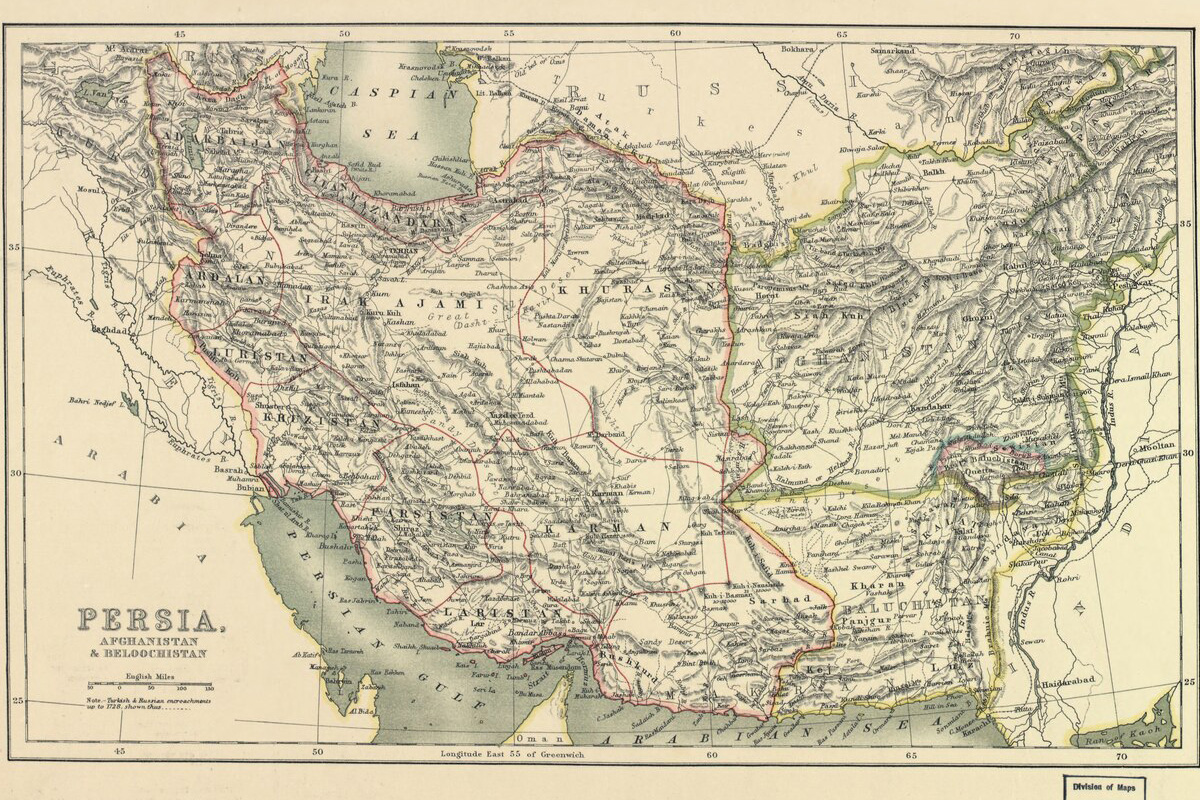

Lenin described a similar process all the way back in 1916. Already by this time, he noted how the world market was carved up between a collection of industrial trusts and cartels, and by the major capitalist powers that stood behind them.

“The enormous growth of industry and the remarkably rapid concentration of production in ever-larger enterprises are one of the most characteristic features of capitalism.”

So begins Lenin’s masterpiece Imperialism, which he defined as the “highest stage of capitalism”.

Some of the names of the massive companies that Lenin mentions – like Siemens and General Electric – are still recognisable today. Others, such as Standard Oil and the US Steel Corporation, were founded by infamous robber barons of America’s ‘Gilded Age’ like JD Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, respectively.

Finance capital

Alongside the concentration of production in the hands of these industrial monopolies, Lenin also explained the increasingly important role of finance capital: the big banks that lend money to businesses, direct investment around the economy, and own controlling shares of many major corporations.

Back then, this tendency was most clearly embodied in the figure of JP Morgan, the kingpin of Wall Street.

Morgan personified the dog-eat-dog nature of capitalism. The notorious financier took advantage of every economic crisis – such as the panic of 1907 – to snap up failing businesses and banks. In doing so, he was able to centralise ever-greater wealth and power in his hands.

The same can be seen with today’s humongous financial houses. JP Morgan’s eponymous investment bank, for example, is still up there with the big boys, with around $3.5 trillion in ‘assets under management’ (AUM). Morgan Stanley, meanwhile, the firm founded by his grandson, has a slightly larger fortune under its auspices.

And the banking sector has only become more consolidated in the wake of each capitalist crisis.

Around 9,000 American banks failed between 1929-33, as a result of the Wall Street Crash and the onset of the Great Depression. The 2007/08 financial crisis, meanwhile, accelerated a decades-long process of decline in terms of the number of US commercial banks.

By 2015, financial concentration in the USA had reached its peak, with the five largest banks controlling over 56 percent of total commercial assets. At this zenith, between them, just three firms had 42 percent of assets in their vaults.

More recently, JPMorgan Chase (them again) and Swiss-based UBS bought up First Republic and Credit Suisse, respectively, when contagion spread following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

These institutions are relative pygmies compared to the real Goliaths of finance, however.

Vanguard and BlackRock are the largest asset managers in the world, with an estimated $10.4trn and $11.6trn AUM, respectively. This includes pools of money accumulated from household savings and pension pots, which is then invested in things like stocks and bonds.

“In so doing,” Lenin outlines, these financial firms “transform inactive money capital [i.e. ordinary people’s savings] into active, that is, into capital yielding a profit; they collect all kinds of money revenues and place them at the disposal of the capitalist class.”

On this basis, Lenin continues, “the banks grow from modest middlemen into powerful monopolies having at their command almost the whole of the money capital of all the capitalists”.

Technically, institutional investors like BlackRock and Vanguard do not directly ‘own’ any assets. Rather, they manage other people’s money. In reality, however, they exert a huge influence over the rest of the corporate world.

At least one of these two firms is in the top three largest investors for every big business in the S&P500 stock market index. As major shareholders, this grants them representation and decision-making power in the boardrooms of all the most important industrial monopolies.

In fact, studies have shown that these gigantic asset managers are often involved in a practice known as ‘horizontal shareholding’: controlling significant stakes in several competing companies within the same industry.

In other words, even where there is a semblance of competition within a sector, it is likely that the same small cabal of billionaires and bankers are pulling the strings behind the scenes.

This is no conspiracy, but an objective fact.

Back in 2011, for example, a team of researchers in Switzerland examined the connections between 43,000 multinational corporations, extracted from a database of over 13 million companies and investors worldwide.

They found that just 147 of these firms controlled around 40 percent of the wealth in their model of the global economy. The top 50 superconnected ‘nodal points’ in this capitalist network were almost all financial institutions of some kind.

And since then, this concentration of economic power is likely to have grown, with the rise of mammoth money managers like BlackRock and Vanguard.

So much for the idea that “we are all capitalists now”. Far from ‘democratising’ capitalism and ‘distributing the means of production’, by giving Joe Public a stake in the corporate economy, the stock market and credit system have only intensified the domination of finance capital – that is, the dictatorship of the banks.

“‘Universal distribution of means of production’ – that, from the formal aspect, is what grows out of the modern banks,” Lenin elaborates in Imperialism. “In substance, however, the distribution of means of production is not at all ‘universal’, but private, i.e. it conforms to the interests of big capital, and primarily, of huge, monopoly capital.”

“The ‘democratisation’ of the ownership of shares,” he concludes, “is, in fact, one of the ways of increasing the power of the financial oligarchy.”

Industrial integration

Another tendency that Lenin outlines – one that further consolidates production under the dominion of the major monopolies – is that of combination: bringing together different industrial processes under a single umbrella.

“A very important feature of capitalism in its highest stage of development,” Lenin states, “is so-called combination of production; that is to say, the grouping in a single enterprise of different branches of industry.” These, he explains, “either represent the consecutive stages in the processing of raw materials…or are auxiliary to one another”.

Today, economists typically refer to these trends as vertical and horizontal integration.

The latter may refer to the consolidation that takes place within a given industry as a result of mergers and acquisitions, with one or another monopoly buying up its competitors.

Similarly, having conquered a particular domain, established firms will often branch out into adjacent markets – using their size and scale to muscle into related industries, in the hope of seizing a chunk of the profits that currently go to other companies.

Vertical integration, meanwhile, is where existing monopolies buy up their suppliers (below) and distributors (above), in order to reduce their costs and make profit at every stage of the supply chain.

Nowhere can these tendencies be seen more clearly than in the technology sector.

Big Tech firms like Apple, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google’s parent company) are themselves the product of the shakeup and consolidation that occurred following the bursting of the dotcom bubble at the turn of the millennium.

Consequently, today, 90 percent of internet searches are made through Google; 83 percent of web browsing is conducted on either Chrome (Google) or Safari (Apple); 95 percent of operating systems installed are designed by Google (Android), Microsoft (Windows), and Apple (iOS and macOS); and more than 80 percent of e-books are sold on Amazon.

Having established a relative monopoly in one area, meanwhile, all of these companies have bought up startups and potential rivals, widening the moat around them to keep out future competitors. And from this fortified position they have invaded nearby fields to expand their territory.

On its road to becoming Alphabet, for example, Google bought up YouTube (the popular video service) and DeepMind (a leading AI developer). Similarly, having built up his billions through Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg splashed the cash on WhatsApp and Instagram to create Meta.

Microsoft, likewise, has made deeper forays into the gaming and social network markets with its purchases of Activision Blizzard and LinkedIn, respectively, which came at a total cost of around $95 billion. And Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has forged a corporate empire spanning online retail, digital media and streaming, and cloud computing.

At the same time, all of these oligopolies are making great efforts – and spending extravagant sums – to break into nascent markets and forefront industries like health tech, self-driving cars, quantum computing, and (of course) artificial intelligence.

The IT sector also provides a modern example of vertical integration. Not satisfied with monopolising the digital world, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, et al. are also looking to control the physical IRL infrastructure of the internet: from building servers to designing software; from laying cables under the sea, to processing data in the cloud.

Silicon and gold

The overall result is that Big Tech now has enormous gravity within the world economy, and particularly within the stock market.

The markets have been on a rollercoaster ride recently, thanks to Trump’s tariff threats. Earlier this year, meanwhile, trading floors gasped at news of a new wave of AI challengers from China.

Before all this turbulence, however, hype in US tech firms was driving share prices ever higher. Around a year ago, 20 technology-focussed companies accounted for over a third (35.8 percent) of the ‘value’ of the S&P500.

Even today, at the time of writing, the ‘Magnificent Seven’ – Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Tesla (in descending order) – have a combined worth of around $15 trillion, making up nearly as big a share of the stock market (one third) as the top 20 tech businesses did previously.

Furthermore, it is clear that Silicon Valley is making super profits. Looking down from their monopolistic castles, Bezos, Zuckerberg, Musk, and co. have been raking in billions.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, as pent-up demand crashed up against supply-side bottlenecks, profiteering monopolies across the board made a killing, in what some commentators dubbed ‘greedflation’.

The revenues and share prices of the top tech companies soared in this period. And AI mania has helped to maintain this momentum, fuelling a contemporary California gold rush – only this time with Palo Alto at its epicentre.

The US tech sector is a giant amongst giants when it comes to profit-making.

In a study of the biggest 4,000 firms across the world, consultants McKinsey found that the largest 500 monopolies increased their share of global profits from 81.5 percent to 91.2 percent between 2005-09 and 2015-19. Within this, the top 100 have boosted their profit share from 45.5 percent to 48.3 percent.

Notably, US corporations have hoovered up money. According to McKinsey’s report, companies based in North America (primarily the USA) increased their share of worldwide profits from 50 percent to 77 percent over this same period.

This jump was driven, in particular, by ‘high technology’ businesses. These account for almost 28 percent of North American profits, with a ‘profit pool’ growth from $66 billion to $116 billion in these years.

US monopolies in the pharma and medical, advanced industrial (automobiles, aerospace, defence, electronics, semiconductors), and media sectors have also seen their mass of profits expand. But they come in a long way behind Big Tech.

No wonder capitalists from other parts of the world – backed by their own imperialist states – are trying to storm the walls surrounding the tech market, in order to seize a slice of the treasure currently hoarded by the kings of Silicon Valley.

This is why the arrival of DeepSeek and other Chinese AI firms has caused such alarm in the upper-echelons of American society. From East Coast bankers to West Coast tech bosses: today’s modern-day robber barons have no desire to share their loot.

Division and redivision

As Lenin explains, this fight amongst the major monopolies to divide – and redivide – the world market between them is a key characteristic of the epoch of imperialism.

“Monopolist capitalist associations, cartels, syndicates and trusts first divided the home market among themselves and obtained more or less complete possession of the industry of their own country,” he outlines. “But under capitalism the home market is inevitably bound up with the foreign market. Capitalism long ago created a world market.”

Such imperialist rivalry can be seen not only in AI, but in all the key industries. And, increasingly, it is the rising power of Chinese capitalism that is coming out on top.

As Lenin notes, a carve up of any market between existing monopolies “does not preclude redivision if the relation of forces changes as a result of uneven development, war, bankruptcy, etc.”.

In addition, new technologies open up new markets for exploitation. And Chinese monopolies, supported and nurtured by the capitalist state, have gained a firm foothold in many of these.

The electronic vehicle (EV) market graphically illustrates this process.

The car industry was formerly dominated by automobile monopolies from the USA, Europe, and Japan, with household names like Ford, Volkswagen, and Toyota.

For decades, these manufacturers have generally focussed their efforts on designing and producing vehicles based on internal-combustion engines. This has allowed dynamic Chinese firms – often with a background in batteries and software – to surge ahead in the development of EVs.

China is the world’s biggest automobile exporter, shipping almost 5 million cars a year beyond its borders. The country also accounts for over three-quarters of the global EV market, helped by bumper internal sales to Chinese drivers.

Benefitting from this huge home market, and aided by state subsidies, Chinese car monopolies like BYD have established a strong position in the EV industry.

By volume, the Shenzhen-based firm has surpassed Elon Musk’s Tesla in terms of EV sales. And it is setting up factories across the world to circumvent tariff barriers and further penetrate foreign markets.

An important factor in BYD’s rise has been its ability to master the art of vertical integration.

BYD started life in 1995 making batteries, and only ventured into producing hybrid vehicles in 2003. Today, alongside manufacturing EVs, the Warren-Buffett-backed business is second-place in the battery industry (behind CATL, another Chinese company), with almost 16 percent of the market – powering not only its own cars, but also those of its rivals.

In turn, BYD has control over the rest of its supply chain: from the mining and processing of lithium for its batteries; to the production of in-car computer chips; to the distribution and shipping of its vehicles.

This allows the multinational carmaker to control costs and maximise profits at every stage in the production process. And it is what makes BYD’s EVs so competitive on the world market – hence the trade barriers being erected by the US and EU to keep out Chinese exports.

Turbulence, tariffs, and trade war

The current trade war is an example of the turbulence that monopoly capitalism breeds, as the different massive multinationals look to increase their profits and expand their markets at the expense of their rivals.

The economic compulsion of competition forces all the monopolies to continually invest in new technologies and ever-greater productive capacity. The result is eye-watering levels of overproduction on a world scale – a global glut of goods, which saturated markets cannot absorb.

Protectionist measures are a response to this: an attempt to prevent the most prolific producers dumping their excess on foreign markets.

Take the automobile industry. “Chinese factories could perhaps turn out nearly 45m cars a year, equivalent to around half of all global sales, yet they operate at only 60 percent of that capacity,” reports the Economist magazine, adding: “Oversupply has led to a vicious price war.”

This explains the sky-high tariffs now imposed on Chinese vehicles. And it also highlights why, according to the same article, China-based firms like Chery, Geely, and SAIC are increasingly looking to break into new markets in the Middle East, Latin America, Africa, and South-East Asia.

Or take the steel industry. China produces more steel every year than the rest of the world put together: around one billion tonnes per year. But the country has no need for all of this internally. It therefore exports a sizable sum of steel – over 90 million tonnes in 2023. This is more than the annual output of the USA or Japan.

Cheap Chinese steel is therefore flooding the world market, pushing down prices and leading to a crisis for steel producers everywhere. Again, this has led to large tariffs. And it is a major factor behind the troubles at the Port Talbot and Scunthorpe steelworks, where workers are threatened with a jobs massacre.

Alongside tariffs and competition over markets, imperialism also means geopolitical struggles over resources.

To build EVs and other high-tech commodities, for example, monopolistic manufacturers require access to various vital raw materials. This includes metals and minerals like lithium, nickel, and cobalt. And increasingly, the mining and processing of these is dominated by Chinese firms, which account for 60 percent, 65 percent, and 70 percent, respectively, of the global supply of these metals.

Similarly, China has a monopoly position when it comes to the extraction and refinement of rare-earth minerals. These form a critical input for everything from solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries, to smartphones, digital cameras, and computer monitors.

Ensuring control over these resources is an important element in the thinking inside Washington and Beijing.

In the Congo, imperialist competition for key minerals is fuelling conflict and catastrophe. Meanwhile, the desire to plunder rare-earth deposits and mineral wealth – and thereby circumvent Chinese export controls – is a significant consideration in the ‘deals’ that Trump is seeking to secure over Greenland and Ukraine.

Computer chip chaos

Equally important is the struggle over silicon – or, more precisely, silicon microchips. These tiny devices power the models, software, and algorithms upon which AI is based. And they are a vital component in many other commodities besides.

But while tech titans like Google, Open AI, and DeepSeek clash in the cloud, several key stages of chip production are highly monopolised.

American computing giant Nvidia is estimated to control around 82 percent of the market for standalone graphics processing units (GPUs), for example. Half of its revenue, meanwhile, comes from four companies: Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet.

Further down the supply-chain, just one firm – the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – accounts for almost two-thirds of the global semiconductor ‘foundry’ market (the production, rather than the design, of computer chips).

This adds an extra dimension to the sabre-rattling between US imperialism and China over Taiwan. After all, the disputed island is home to the production of more than 90 percent of the most advanced semiconductors.

Similarly, one Dutch company called ASML almost exclusively makes and supplies the highly-complex lithography machines used to etch silicon in the chip manufacturing process.

On the one hand, then, this monopolisation has created incredibly efficient and specialised businesses, capable of serving the entire planet’s need for pivotal tech products.

On the other hand, however, this concentration has also made the world economy extremely fragile; vulnerable to any shock or disruption to the intricate web of production and distribution that has evolved in recent decades, on the foundations of globalisation and free trade.

The pandemic revealed this starkly, as supply-chains spasmed in the face of lockdowns and bottlenecks. The price of microchips swung wildly, as the industry was faced first with painful shortages and then with oversupply, demonstrating vividly the anarchy of the capitalist market.

Today’s rumbling trade war is proving the same point, as US imperialism applies pressure on companies like AMSL and Nvidia to restrict their exports to China, in the hope of strangling the country’s flourishing – rival – tech industry.

Washington is playing with fire here, however. America may have a tight grip over certain choke points when it comes to the production of microchips. But it does not ‘hold all the cards’ when it comes to its trade war with China, as the example of minerals attests.

Indeed, the monopolisation of global production means that the manufacturing of many commodities is concentrated inside China. For over a third of the products that Uncle Sam imports from China, the Asian country is the dominant supplier, meeting 70 percent or more of US demand.

In other words, the White House will have great difficulty cutting China out of the picture when it comes to trade. Monopolisation and globalisation have combined to create an extremely interconnected and interdependent world economy. And this cannot be unravelled without causing immense damage, in the form of soaring inflation and economic contraction.

All of this graphically demonstrates how production has become enormously socialised; how the development of the productive forces is increasingly clashing with the barriers of private property and the nation state.

And it reveals how, far from bringing about stability, monopolisation under capitalism is a recipe for instability and chaos at every level.

As Lenin underlines in Imperialism, replying to the arch-opportunist Karl Kautsky, “the apologists of imperialism” mistakenly believe “that the rule of finance capital [and the monopolies] lessens the unevenness and contradictions inherent in the world economy, whereas in reality it increases them”.

“On the contrary,” he concludes, “the monopoly created in certain branches of industry increases and intensifies the anarchy inherent in capitalist production as a whole.”

Stagnation and decay

Lenin goes on to explain how monopolisation “inevitably engenders a tendency of stagnation and decay”, stifling the development of the productive forces – i.e. science, technology, industry, and so on.

“Since monopoly prices are established, even temporarily,” he continues, “the motive cause of technical and, consequently, of all other progress disappears to a certain extent and, further, the economic possibility arises of deliberately retarding technical progress.”

Even bourgeois analysts are coming to similar conclusions today, fearing that monopolisation is a key factor behind the anaemic productivity growth that has plagued capitalism globally in recent decades.

As the Economist journal reports:

“The very success of America’s tech giants has provoked concern that they have become too powerful, and that their dominance is harming the economy and stifling its dynamism.

“Thomas Philippon of New York University has documented the rise in corporate concentration in America since the 1980s: big companies have taken a larger and larger share of corporate revenues; corporate profits in general have risen as a share of economic output; and companies, especially in the most concentrated sectors, have transformed less of their profits into new investments and more into share buybacks.

“Added up, that threatens to be a recipe for slower productivity, weaker growth, and higher inequality.”

Similarly, in his book What went wrong with capitalism?, libertarian author Ruchir Sharma argues that a toxic combo of state intervention and monopolisation lies behind the ‘productivity paradox’ that has baffled bourgeois economists for some time now.

“Annual productivity growth is falling on average in the industries where the biggest companies are tightening their control most rapidly,” the Rockefeller financier writes.

“Productivity is falling across the board in these industries, particularly in the laggard companies but even in the leaders, for two basic reasons. With no pressure from below the leaders don’t need to invest as much, and if they do add more or better service, they only ‘cannibalise on their own market shares’.”

Instead of encouraging dynamic new startups to enter the market, Sharma suggests, capitalist governments have propped up failing firms and protected stodgy incumbents. The result is an undead army of unproductive ‘zombie’ businesses, combined with a herd of senile, lumbering corporate giants that crushes any smaller, fledgling companies in its path.

Logic of competition

Like the godfather of libertarianism, Friedrich Hayek, Sharma frames the question of monopolisation in purely ideological or political terms.

For these free-market fanatics, monopoly capitalism is merely the creation of irresponsible policymakers and unprincipled politicians, who have allowed lobbyists and lawyers to rig the system in favour of existing plutocratic interests.

No doubt the system is rigged, to the benefit of the billionaires and bankers. But this does not explain why capitalism is the way it is.

In their economic writings, Marx, Engels, and Lenin all showed how monopolisation is the product of an objective process, not a ‘political choice’.

The dynamics of private property and production for profit mean that competition inevitably turns into its opposite.

This is aptly illustrated by the boardgame Monopoly. Everyone starts out on an equal footing. And the rules are the same for everyone. Nevertheless, one player eventually owns and controls everything. That is the cold, callous logic of capitalist competition.

Similarly in real life: inefficient minnows go out of business, and are gobbled up by their bigger, stronger rivals. Production thereby becomes more concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Over time, accelerated by crises, this leads to the emergence of powerful monopolies.

“[T]he rise of monopolies,” Lenin states in Imperialism, “as the result of the concentration of production, is a general and fundamental law of the present stage of development of capitalism.”

In turn, monopoly itself becomes a lever for further monopolisation.

Larger companies forge ‘economies of scale’: cost savings arising out of the organisation and planning that is enabled at a certain size of production and distribution. And they begin to accumulate – and gain access to – the capital needed to invest in new technologies and techniques, further boosting their productive advantage in relation to smaller competitors.

Today, the vast quantity of capital required to compete in the most important industries acts as an enormous barrier to entry for new firms.

According to some estimates, for example, 50-60 years ago, the construction costs of an advanced microchip factory (or ‘fab’) would come to around $30 million in today’s money. Modern fabs built by TSMC, by contrast, cost about $20 billion each.

This allows the biggest imperialist powers to squeeze out smaller nations. Even the EU, let alone isolated countries like Britain, cannot hope to compete with the massive sums that the USA and China are able to throw at their industries.

Failed European and UK attempts to break into the green technology sector – like battery firms Northvolt and Britishvolt, respectively – are a testament to this. Likewise, how can anyone else match the hundreds of billions that the US and China are pouring into AI?

The walls and moats protecting the established monopolies, in other words, are getting ever taller and wider.

Need for socialism

For liberals and libertarians, the solution to all this turmoil is to go backwards: to call for ‘more choice’ – for greater competition and freer markets; to demand the breaking up of the major monopolies through ‘antitrust’ laws and regulations.

There are others, meanwhile, who call for protectionism and economic nationalism: for the domination of the multinational monopolies to be replaced with ‘buying local’ and the promotion of ‘national champions’.

Both these suggestions are completely utopian and reactionary, however. As explained, monopolies have arisen precisely because they are more efficient and productive; in other words, because they represent a development of the productive forces.

Similarly, production has become highly socialised and globally interconnected – again, because this increases productivity through greater economies of scale, international division of labour, and specialisation.

To propose the disbandment of the monopolies – internationally or in any one country – is therefore to suggest a regression to a lower level of economic development. In concrete terms, this means making society poorer.

“To concentrate these scattered, limited means of production, to enlarge them, to turn them into the powerful levers of production of the present day – this was precisely the historic role of capitalist production and of its upholder, the bourgeoisie.”

So explains Engels in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, discussing the progressive role that capitalism once played in developing the productive forces.

In this process, he outlines, “the whole of a particular industry is turned into one gigantic joint-stock company; internal competition gives place to the internal monopoly of this one company”.

“In the trusts, freedom of competition changes into its very opposite – into monopoly; and the production without any definite plan of capitalistic society capitulates to the production upon a definite plan of the invading socialistic society.”

The result is the contradictory situation we find today, where socialised production and elements of planning exist alongside private ownership and the anarchy of the market.

Increasing state intervention, with endless bailouts of the big banks and monopolies in response to every crisis, is a recognition of this contradiction; a tacit admission that the productive forces have outgrown the restrictions of private property and the nation state – i.e. that production has become completely socialised, but with private appropriation by the capitalists of the wealth created by the working class.

The solution is not to turn back the wheel of history, by attempting to break up the banks or monopolies, or by praising the wonders of ‘small enterprise’ and parochial production.

Instead, we must take the immense levels of organisation and planning that have been created by capitalism, and put these economic forces under the collective ownership and conscious democratic control of the working class.

Take monopolies like Walmart, for example, with an annual revenue of over $600 billion and a workforce of 2.1 million employees.

This one mega-company is bigger than entire past planned economies like the Soviet Union, as highlighted by the authors of The People’s Republic of Walmart. And inside this multinational firm, there is an extraordinary amount of planning – from the farms and the factories, through to the shop and the supermarkets.

In the hands of its billionaire owners, such technology and logistics are merely a means for lining the pockets of Walmart’s shareholders. But in the hands of the working class, this would be the basis for distributing life’s necessities across continents, and ensuring a decent diet for all.

“The solution,” Engels therefore explains, “can only consist in the practical recognition of the social nature of the modern forces of production, and therefore in the harmonising with the socialised character of the means of production.”

“And this,” he concludes, “can only come about by society openly and directly taking possession of the productive forces which have outgrown all control, except that of society as a whole.”

The epoch of imperialism, in this respect, is a transitory phase – preparing the material conditions for a new, higher form of society: socialism and communism.

“Capitalism in its imperialist stage leads directly to the most comprehensive socialisation of production,” Lenin writes. “It, so to speak, drags the capitalists, against their will and consciousness, into some sort of a new social order, a transitional one from complete free competition to complete socialisation.”

“This in itself determines [imperialism’s] place in history,” Lenin ends with, “for monopoly that grows out of the soil of free competition, and precisely out of free competition, is the transition from the capitalist system to a higher socio-economic order.”

But this transition won’t happen automatically. Instead, as long as the capitalist system remains, the incredible potential of modern technology and planning will be squandered – and even worse, turned into a destructive force that breeds war, climate catastrophe, and misery.

The only way forward for humanity is through world socialist revolution.

To win this real-life game of monopoly, the working class must organise and mobilise to give Mr Moneybags the boot, seize the property of the billionaires, and take over the whole board, in the fight for a communist future.