Felix Lighter reviews the latest offering by British director Mike Leigh, who provides a shocking and emotional portrayal of the infamous massacre that took place in Manchester almost two centuries ago.

The mark of a good film is that it stays with you long after the final credits have rolled and you have left the cinema. Peterloo, a superb new film by Mike Leigh, certainly does that.

The brutal massacre of working class people that took place in Manchester in August 1819 has tended to be downplayed in most history books, despite reflecting important developments in 19th century England. This film should help to correct this neglect.

What was the historical background to the Peterloo massacre? The end of the Napoleonic wars with France, following the defeat at Waterloo in 1815, did not lead to the expected economic advances for the English economy. In fact, the ending of huge war contracts dished out by the government had left the economy all too exposed, with declining exports revealing the depth of the crisis. In addition, hundreds of thousands of soldiers were now out of uniform and looking for work.

The decline in rural employment, with workers being pushed towards the towns and cities, had resulted in misery for many. Rising prices and new taxes imposed by a cash-strapped government hit ordinary people hard.

In addition, the imposition of the Corn Laws had pushed the price of wheat – and therefore bread – up. As a result, bread riots took place in many towns between 1815-16. Wage cuts only made things worse. After all, the welfare state did not exist then.

Exploitation and repression

The film shows the harsh nature of life in the factories and its grinding effect on those who worked in them. Those who could not get work were left at the mercy of the local arrogant magistrates and the factory bosses who backed them.

The film shows the harsh nature of life in the factories and its grinding effect on those who worked in them. Those who could not get work were left at the mercy of the local arrogant magistrates and the factory bosses who backed them.

Increasingly, as the film outlines, a mood of radical protest began to take shape around the country – and especially in the north of England. The scandal of “rotten boroughs” meant that the whole of Lancashire only had two MPs, the same number as Old Sarum near Salisbury, which never had more than eleven voters in total and was “in the pocket” of the Pitt family. Political and economic reform was increasingly being demanded by the masses.

The response of the government, dominated by the rich and powerful, was to suppress the movement from below. They were terrified of revolution. And politicians like Sidmouth were happy to feed on this for their own ends.

Hand-in-hand with the political rise of the capitalist class came the imposition of brutal and unjust laws to protect their interests. In 1817, fearful of revolt and revolution, the government suspended Habeas Corpus and passed the Gagging Act. This outlawed public meetings and rallies and suppressed radicals.

However, as Peterloo shows, the mood of protest only got stronger, with meetings becoming ever larger and more open. Not only men but women too started to organise. The film uses many of the actual reported words, writings and speeches of those historical characters featured in the film – an indication of its accuracy in showing the build up to the massacre itself.

By 1819, mass meetings to demand reform were taking place across the country, much to the horror of the establishment. In June, the Pentrich Rising took place. This was brutally put down by local forces, with three of its leaders later being executed. A government spy, William Oliver, is portrayed in the film as being involved both at Pentrich and later on in Manchester itself.

Massacre

In Manchester, it was decided to hold what was called “The Great Assembly”, set to take place at St. Peter’s Field on 16th August 1819. To add authority to the event, it was also agreed to invite Henry “Orator” Hunt (played in the film by Rory Kinnear) to speak as the main attraction.

In Manchester, it was decided to hold what was called “The Great Assembly”, set to take place at St. Peter’s Field on 16th August 1819. To add authority to the event, it was also agreed to invite Henry “Orator” Hunt (played in the film by Rory Kinnear) to speak as the main attraction.

It is believed that between 60,000 and 80,000 assembled on that fateful day. Budget restrictions tend to limit the crowd’s numbers shown in the film. Nevertheless, the rally is fairly depicted, based on later reports and illustrations.

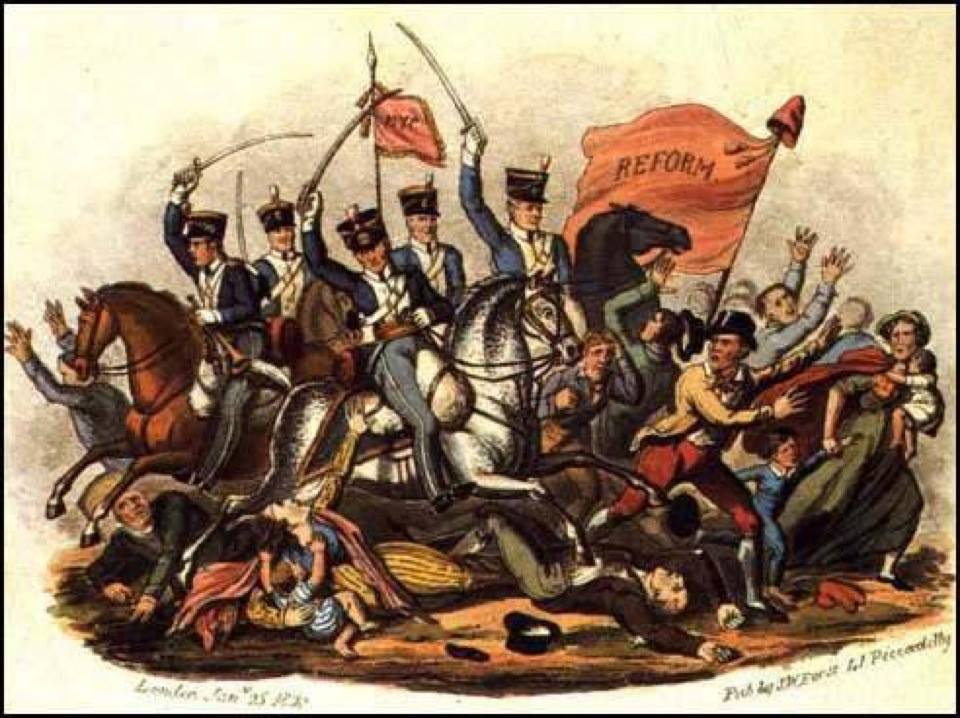

The mood was angry and the local magistrates, assembled in a room overlooking the rally, quickly ordered the forces of the 15th Hussars and the local Yeomany (a motley collection of volunteer thugs, which one paper called the “young Tory Party in arms”) to clear the square by force. The Riot Act was read to provide legal cover, but nobody could hear it.

The charge was violent and uncontrolled, with the crowd having no means of escape. Some of the Hussars tried to restrain the yeomanry, but others joined in the violence out of fear and hatred of the masses.

Within ten minutes,15 people were dead or dying and a further 400-600 were injured. It was said that the troops went out of their way to target women and children.

The graphic depiction of the massacre itself comes as quite a shock (for a Mike Leigh film, at least) and has a considerable emotional impact as a result.

Rise like lions

Interestingly, the film draws attention to differences between the more reformist views of those like Hunt and the revolutionary mood amongst local radicals. In particular, Hunt comes across as being keen not to provoke the local authorities. This despite warnings that they were going to use violence, indicating that the organisers of the rally should be prepared and armed. Hunt wins the day, leaving the masses at the mercy of the Hussars and the yeomanry.

Interestingly, the film draws attention to differences between the more reformist views of those like Hunt and the revolutionary mood amongst local radicals. In particular, Hunt comes across as being keen not to provoke the local authorities. This despite warnings that they were going to use violence, indicating that the organisers of the rally should be prepared and armed. Hunt wins the day, leaving the masses at the mercy of the Hussars and the yeomanry.

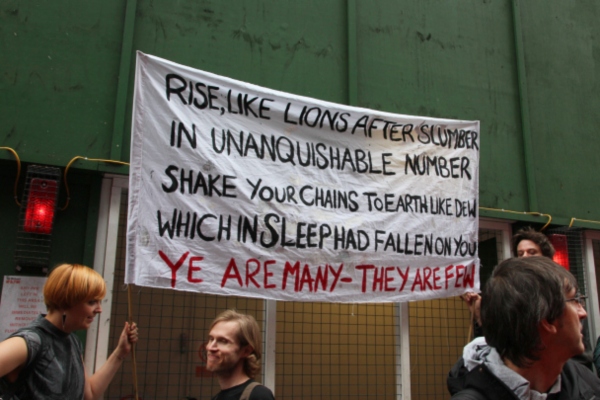

The Manchester Observer called the massacre “Peterloo”, linking it to the famous and bloody battle of 1815. Shelley later wrote his epic poem The Mask of Anarchy based on these events.

Although the film ends with assembled journalists walking through the aftermath of the carnage, vowing to expose what has happened and bring those responsible to justice, no such result ever occurred in reality.

Instead, the state imposed new repressions, including the so-called “six acts” to crush all opposition, resulting in virtually all known radicals being arrested or fleeing. Indeed, one of the final scenes in the film shows the Prince Regent and the leaders of the government oblivious to the bloodshed they have allowed to occur.

At one point, a discussion is held by two members of the family whose fate we follow through the picture as to what things will be like at the end of the century. The character of Nellie (played by Maxine Peake) says she hopes for better things for those who will come after them. But the response is pessimistic – and with good reason.

Capitalists like to pretend that things are much better now. But many will recognise echoes of today’s conditions in the film’s portrayal of 1819 Britain.

Peterloo is a marvelous film that should be seen by all. More than that, we should put Shelley’s words into practice and rise like lions – because we are many and they are few.