We publish here the second part in a series by Alan Woods looking at the theoretical differences between Marxism and anarchism. These articles were originally published as an open letter in response to an article by ‘Black Flag’, an anarchist group in Brazil, continuing the analysis presented in this earlier series on the ideas of Marxism vs anarchism.

In this second part, Alan examines the role of leadership in class struggle, the relationship between Marxists and the mass organisations, the origins of bureaucracy, and how political consciousness develops and changes.

The role of leadership

Black Flag writes:

“The repetitive argument that the working class needs leaders do not differ from any RIGHT WING speech which states that equality is impossible because some must rule and others obey.”

Our anarchist friend speaks of the working class in a very abstract way, but completely ignores the concrete reality. The working class is not one homogeneous mass but is composed of different layers. Some workers are more backward, others more advanced and class conscious. Some are religious and under the influence of the church, while others have broken away from religious prejudices. Some organise unions, others do not.

The reality of the class struggle – something which is clearly a closed book to our anarchist critic – demonstrates the complete falsity of the way he poses the question of leadership. In every factory there is always a group of workers – a minority under normal circumstances – that maintain trade union organisation and stand up to the bosses. These are the “natural leaders” of the working class.

Even in a strike of half an hour, we will find leadership. And this leadership is not improvised on the spur of the moment but prepared over a whole period of work and struggle. These advanced workers may be Marxists, anarchists, reformists or people of no fixed political views (although this is rarely the case in practice). But invariably they will be people who have earned the right to lead.

We see this in every strike. The question as to whether to strike or not is debated democratically in a mass meeting. Some workers are in favour of strike action and others against. And it frequently occurs that a single intervention by a militant worker can decide the issue. What is this but leadership? The next step is that somebody has to go and put the workers’ case to management. When the time comes to decide who walks through the manager’s door, who do the workers choose? They do not toss a coin to decide, nor do they elect the most backward elements to defend their interests. They will look to the most determined and class conscious elements able to represent them – and yes, also to lead them. It is one-sided to portray leadership as only hindering or pacifying the rank-and-file. Good leaders, who do exist, can also inspire the rank-and-file into taking action.

All this is really ABC for any worker with even the slightest experience of the class struggle. Only people completely ignorant of the workers’ movement or blinded by anarchist prejudices can have the slightest doubt about the importance of leadership at the shop floor level.

How the working class draws revolutionary conclusions

The working class does not automatically and en masse arrive at revolutionary conclusions. If that were so, the task of party-building would be redundant. The task of transforming society would be a simple one, if the movement of the working class took place in a straight line. But this is not the case. Over a long historical period, the working class comes to understand the need for organisation. Through the establishment of organisations, both of a trade union and, on a higher level, of a political character, the working class begins to express itself as a class, with an independent identity. In the language of Marx, it passes from a class in itself to a class for itself. This development takes place over a long historical period through all kinds of struggles, involving the participation, not just of the minority of more or less conscious activists, but of the “politically untutored masses”, who, in general, are awakened to active participation in political (or even trade union) life only on the basis of great events.

The working class does not automatically and en masse arrive at revolutionary conclusions. If that were so, the task of party-building would be redundant. The task of transforming society would be a simple one, if the movement of the working class took place in a straight line. But this is not the case. Over a long historical period, the working class comes to understand the need for organisation. Through the establishment of organisations, both of a trade union and, on a higher level, of a political character, the working class begins to express itself as a class, with an independent identity. In the language of Marx, it passes from a class in itself to a class for itself. This development takes place over a long historical period through all kinds of struggles, involving the participation, not just of the minority of more or less conscious activists, but of the “politically untutored masses”, who, in general, are awakened to active participation in political (or even trade union) life only on the basis of great events.

As we have seen, the working class in general learns from experience, especially the experience of the class struggle. Many workers have passed through the experience of strikes: they have known victories and defeats and have drawn certain lessons from their experience. Consequently, experienced worker militants possess the necessary knowledge to organise and lead a strike. They do not require advice from revolutionaries – whether Marxists or anarchists – in order to perform this function.

However, when it comes to revolutionary situations, the question is posed differently. How many workers have gone through the experience of an all-out general strike? Not very many. But the general strike is not the same as an ordinary strike. It challenges the rule of capital in a direct manner. Who runs society: the bosses or the workers? In other words it poses the question of power. A general strike cannot therefore be approached in the same way as a normal strike. As a rule it either ends in the working class taking power or in a decisive defeat.

In the past the anarcho-syndicalists thought that a general strike in and of itself would be sufficient to carry out a revolution. But this idea is profoundly mistaken. The capitalists can wait as long as it takes to defeat a general strike, but the ability of the workers to survive without payment, without food for their families, has definite limits. If the strike goes on for too long without resolution, the mood of the workers will begin to decline and the strike will be defeated. Even the stormiest strike in itself cannot solve the question of power. We saw this clearly in France in May 1968, where the greatest general strike in history ended in defeat. And this was precisely a problem of the nature of the leadership. It is one thing to strike against a system, and in doing so to temporarily cripple it, it is quite another to organise the complex and detailed task of disbanding the old government, agreeing how it is to be replaced and then organising the systematic defence of this new social regime. Without a distinct political organisation, visible to the working class and proposing such concrete measures, revolutionary general strikes fizzle out and the old regime recovers its control.

The causes of bureaucracy

Despite, or indeed because of, anarchism’s blanket rejection of authority and hierarchy, anarchist theory ironically lacks any coherent theory of leadership, authority, or power. This is because anarchists treat such phenomena abstractly and uniformly, when in fact there is no such thing as ‘power’ as such. Marxists, as historical materialists, recognise that power emerges from accumulated material inequality and the resulting social contradictions. It is a tool that is created for its wielder – the ruling economic class – and is determined by their ends, which in the final analysis are material ones. The authority that slaves impose onto their owner as they fight for their freedom is not only different from, but diametrically opposite to, the authority of a slave owner oppressing his slaves.

Despite, or indeed because of, anarchism’s blanket rejection of authority and hierarchy, anarchist theory ironically lacks any coherent theory of leadership, authority, or power. This is because anarchists treat such phenomena abstractly and uniformly, when in fact there is no such thing as ‘power’ as such. Marxists, as historical materialists, recognise that power emerges from accumulated material inequality and the resulting social contradictions. It is a tool that is created for its wielder – the ruling economic class – and is determined by their ends, which in the final analysis are material ones. The authority that slaves impose onto their owner as they fight for their freedom is not only different from, but diametrically opposite to, the authority of a slave owner oppressing his slaves.

State power has arisen as economic development has created class divisions, and it serves those divisions. It is inseparable from social antagonisms, and will exist so long as these antagonisms remain. Rather than explaining this, anarchists concentrate on denouncing the power of the ruling class as ‘illegitimate’ and a lie, as if all history were a giant trick miraculously imposed onto the masses by a sinister magician. In doing so, they mystify the very thing they despise. Whilst proudly proclaiming platitudes such as ‘No gods, no masters’, or ‘we are ungovernable’, they remain doomed to being governed because they do not understand the basis of their oppression.

How do we explain the phenomenon of bureaucracy in the workers’ organizations? Our critic turns for help to the nebulous realms of psychology:

“Several researches in the fields of psychology and pedagogy show, however, that the authority and hierarchy, far from favouring, hinder. The Stanford Experiment is a good example of how the concentration of power in one individual can cause problems.”

The Stanford Experiment was carried out at Stanford University in August 1971. It divided a group of student volunteers into “prison guards” and “prisoners” to see how they would react. Some of the “guards” began abusing the “prisoners”. Many have criticised the validity of the experiment, inasmuch as the organiser of the experiment, professor Philip Zimbardo, actively participated in pushing the participants to behave in a certain manner, i.e. he was far from objective in his approach. It was also found that the initial character traits of those involved influenced their behaviour rather than the conditions of the experiment influencing them. There were attempts to replicate the experiment which produced different results.

Has our learned anarchist critic thrown in this passing reference to the Stanford Experiment to give himself an aura of being a knowledgeable person in such matters? Unfortunately, he has chosen poorly, for such an experiment has nothing whatsoever to do with the leadership of workers’ organisations. The workers who join mass organisations are not prisoners and the leaders are not omnipotent prison guards.

Our anarchist critic continues:

“The main complaint in this field is that anarchists opposed the bureaucratic manipulation of the Union by an allegedly revolutionary party. Why, let’s just look at what happens when parties bureaucratically use the Union to realize that the result is always the same: stagnation, corruption, class treason and often sectarianism and authoritarianism. The CUT here in Brazil is the biggest example of this – the Central is connected to the PT, of which until yesterday the Marxist Left was a part of, remember.” [My emphasis]

The implication of our anarchist friend is that all organisations end up as a bureaucratic hierarchy. It is true that organisations like the trade unions that are formed under capitalism, and inevitably come under the pressures of capitalism, can degenerate. The leaders can become corrupted, lose contact with the rank and file and sell out. That has happened many times, including in the case of the Brazilian CUT. However, it is entirely false to treat things in this blanket fashion, as if the history of our movement is nothing but one of bureaucracy and ‘class treason’. It is false to present the relationship between the working class and its leaders in terms of hierarchy and blind obedience (“some must rule and others obey.”). The workers’ movement is generally democratic. The decision to strike or not is decided in a democratic mass meeting. The strike leaders are democratically elected. If they do not act according to the wishes of the workers, they can be recalled and replaced by others. “Rule and obey” does not enter into it.

Instead of merely denouncing this degeneration, we should also strive to understand it. Why do workers’ organisations degenerate? Is it because of the bad character of the workers’ leaders? Is it because they are “hungry for power”, as our anarchist critic seems to believe with his references to individual psychology? Is it the case that degeneration is the inevitable result of setting up a political party and fighting for political power, and that all workers’ parties, always, betray? If that is the case, then the outlook for the working class would be grim indeed. Our anarchist friend does not provide any serious explanation for the phenomenon which he deplores so much. To find the reasons for this degeneration it is necessary to look, not in the misty realms of psychoanalysis, nor in the formal structures of parties, but in the actual functioning of class society.

The workers’ organisations do not exist in a vacuum. They exist in the framework of capitalism, and come under the pressures of capitalism. Under certain conditions even the best organisation can degenerate under these pressures, which exercise their most powerful effect on the leading strata. The formation of a bureaucratic crust is a reflection of that pressure. It is not a product of leadership in itself, but leadership corrupted by the capitalists. Over a long period of time the ruling class has developed highly effective and sophisticated mechanisms for bribing and controlling the workers’ leaders.

Every organisation – anarchist organisations included – always contains the possibility of degeneration. As long as we are compelled to work within capitalist society, we cannot escape from the pressures of capitalism. There is of course no absolute guarantee against the degeneration of any organisation. Life in general, and the class struggle in particular, offers us no guarantees.

The working class has ways of combatting the pernicious influence of the bourgeoisie inside the labour movement. It is necessary to actively participate in the struggle against bureaucracy, to purge the movement of careerists and traitors and to bring the trade unions under the control of the working class. By standing aside from this struggle, one does not help the cause of the socialist revolution but objectively serves the interests of the bourgeoisie and its agents within the workers’ movement, for this leaves the mass organisations in the hands of bureaucrats who, lacking pressure from below, will have no trouble capitulating to bourgeois pressure from above.

Therefore, rather than abstaining from the struggle, we must conduct a systematic struggle within the Labour movement against bureaucracy, and demand that our representatives must be brought under the control of the rank and file. We must demand that every trade union official, local councillor or Member of Parliament should be elected at regular intervals and subject to recall at all times. No workers’ representative should receive a higher wage than that of a skilled worker, and all expenses should be open to the inspection of the rank and file.

These basic principles will serve to purge the workers’ organisations of bureaucrats and careerists and ensure that our representatives genuinely reflect the interests and aspirations of the class, and not their own personal interests and ambitions.

Marxists and the mass organizations

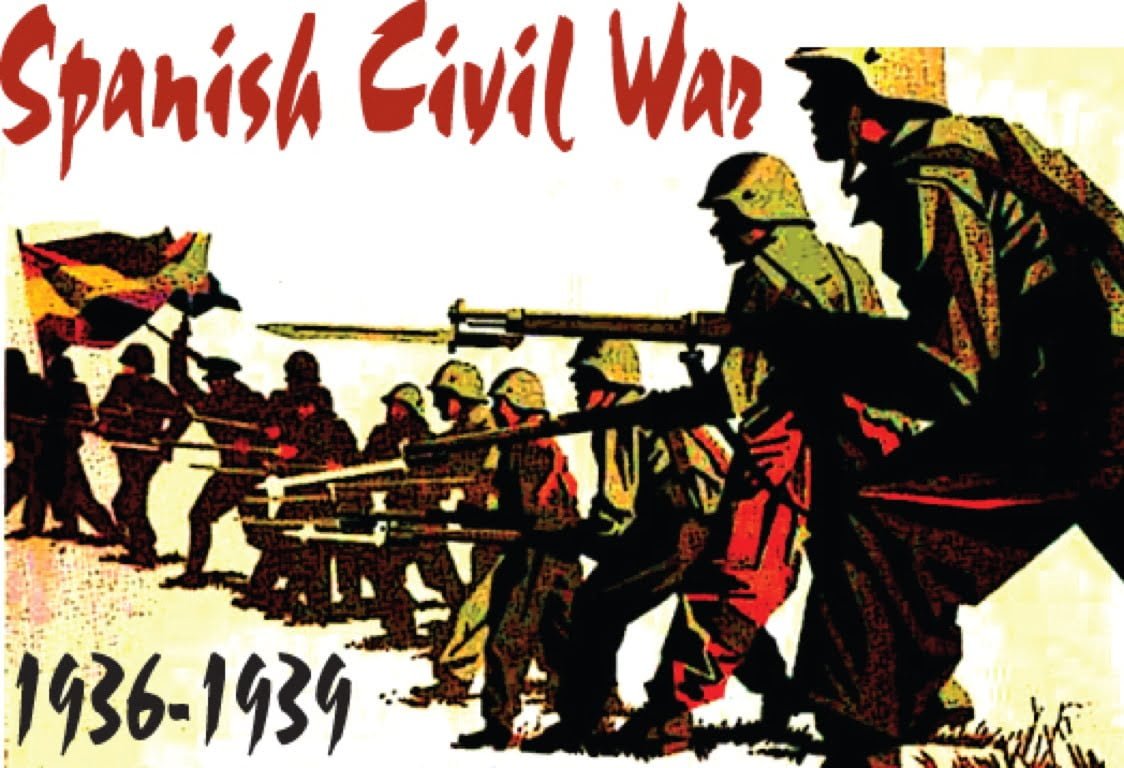

In order to cover his bare backside, our anarchist critic adds insult to injury. He has the audacity to claim that the betrayal of the Spanish CNT leaders during the Spanish Civil war was, “…closer to that of Marxists, as we have seen in the Trotskyist participation of the IMT within the bourgeois regimes of the PT and Syriza.”

In order to cover his bare backside, our anarchist critic adds insult to injury. He has the audacity to claim that the betrayal of the Spanish CNT leaders during the Spanish Civil war was, “…closer to that of Marxists, as we have seen in the Trotskyist participation of the IMT within the bourgeois regimes of the PT and Syriza.”

Regarding our participation in the mass organisations of the working class, our friend thinks he is on to a winner. Like a little boy walking around showing everybody his new shoes, he repeats this fact as though it were a damning condemnation of Marxists in general and the IMT in particular. In resorting to this tactic, he merely parades his ignorance of the working class and its organisations, and his own sectarian arrogance.

Like a repeating groove on a gramophone record, he reiterates the same monotonous tune:

“Alan Woods tries to blame the reformist and bureaucratic wings for the discrediting of the leaderships. It is to be noted that the Marxist Left [Esquerda Marxista], today in the PSOL, until early 2015 was a component part of the Workers’ Party (PT). These Trotskyists saw no problems in asking for votes for Lula and Dilma even considering what the party had become.

“The IMT section in Greece also gave full support to the election of Tsipras, of Syriza, who refused to respond to the popular appeal and resist the austerity demanded by the Troika. In fact, about ‘bureaucrats and careerists’, Alan Woods knows a lot.”

This is a complete distortion of reality. Firstly, no member of the IMT has ever joined any bourgeois regime, either of the PT, Syriza or any other government. What is true that at different times the Marxists have participated in mass parties of the working class in different countries, struggling side by side with the rank and file workers in these organisations to fight against the bureaucracy and advance the programme of revolutionary socialism. In exactly the same way, the Friends of Durruti fought side-by-side with the rank and file anarchist workers of the CNT against the treacherous policy of the anarchist leaders. The CNT leaders, on the other hand, joined a bourgeois government as ministers.

The participation of the Marxists in the mass organisations of the proletariat, far from being a weakness, represents, together with our theoretical clarity and revolutionary intransigence, our main strength. Our participation in these organisations, far from representing participation in the “regime”, is based on an implacable struggle against the bureaucracy in order to win over the workers and youth. You can only help liberate the masses from the influence of reformism by going through with them, step by step, the living struggle in these reformist organisations, pointing out at each step that the reformists cannot solve their problems. The refusal of the anarchists to dirty their hands with the mass organisations of the workers they claim to represent is merely a confession of impotence: sterile abstentionism disguised under a thin layer of pseudo-revolutionary demagogy.

The masses must test the parties and leaders in practice, for there is no other way. The mass of the working class learns from this experience. They do not learn from books, not because they lack the intelligence, as middle class snobs imagine, but because they lack the time, the access to culture and the habit of reading that is not something automatic, but is acquired. This process of successive approximation is both wasteful and time-consuming, but it is the only one possible. In every revolution—not only Russia in 1917, but also France in the 18th century and England in the 17th century—we see a similar process, in which, through experience, the revolutionary masses, by a process of successive approximations, find their way towards the most consistently revolutionary wing. The history of every revolution is thus characterised by the rise and fall of political parties and leaders, a process in which the more extreme tendencies always replace the more moderate, until the movement has run its course. But they can only test out the political parties and tendencies that actually exist in a sizeable form, therefore if revolutionaries are to gain the leadership of the working class in the heat of revolutionary events, there is no other way than through building such an organisation as a part of this living struggle, which is nothing if not political.