Paraphrasing the dialectical philosopher Hegel, Karl Marx remarked that “all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice…the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

“…Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language.” (Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte)

Marx’s famous aphorism is evident today in the sphere of economics. Commentators are groping around in the search for historical parallels to the current crisis. And policy makers are looking to the past in the hope of finding answers for the seemingly insoluble problems they face.

The nearest comparison that anyone can identify for the present crisis is the Great Depression. But as with any analogy, this has its limits. Capitalism today is truly global; the contradictions within the system have been building up for decades; and the working class is far stronger on a world scale. Today’s crisis is therefore even broader and deeper than that of the 1930s.

Nevertheless, this has not stopped the ruling class and its representatives from examining this period in their quest for ‘solutions’ to the present impasse.

And so it is that we now see President Biden attempting to emulate his Depression-era predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt (‘FDR’), who famously brought in his ‘New Deal’ of public work projects and programmes in an effort to (quite literally) dig the economy out of its hole.

But whereas FDR, pushed along by a capitalist class that was desperate for stability, was able to carry out sweeping reforms in his first 100 days, Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package has been far more farcical – squeezed through Congress thanks to a mixture of horse-trading and Byzantine loopholes.

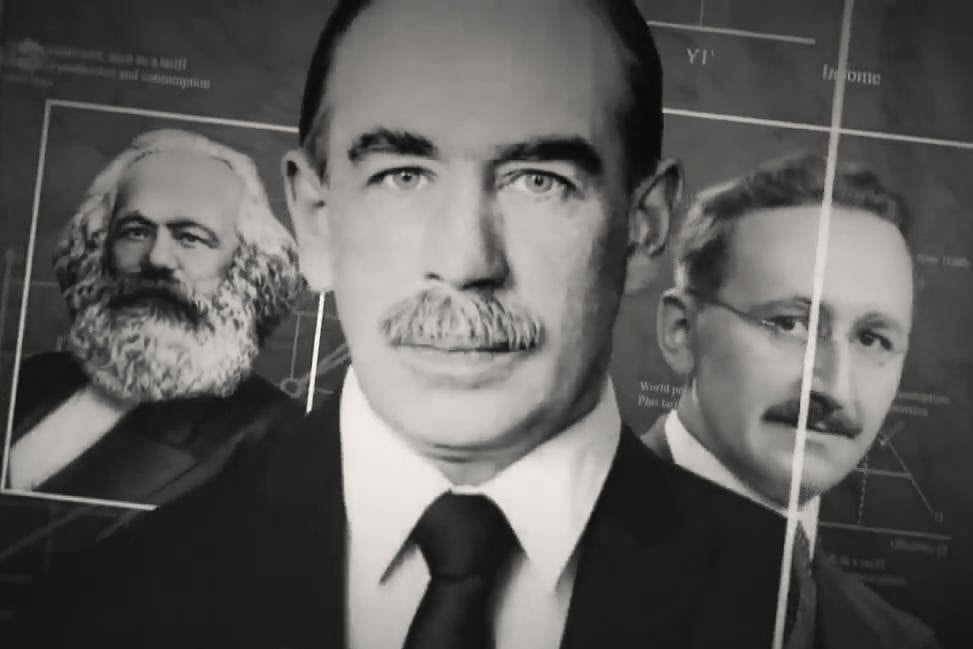

Similarly on the theoretical front. In the 1930s, it was the liberal English economist John Maynard Keynes – with his calls for government-led expenditure and investment – who provided the theoretical framework and economic analysis upon which FDR’s New Deal was based.

Today, bourgeois economists and politicians across the world are once again singing a Keynesian tune. In total, governments have spent an estimated $14 trillion in coronavirus-related fiscal support. Global debt levels are now around 100% of GDP. And central banks have injected a further $9 trillion into the financial system. Yet still the long-term perspective for capitalism is one of continued crises.

Unfortunately, even the left and the labour movement have bought into this liberal Keynesian creed.

In the USA and UK, activists in the Democratic Party and Labour Party respectively have made the demand for a ‘Green New Deal’ a shibboleth of the left. Influential left-wing figures such as AOC have promoted the utopian neo-Keynesian ideas of ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ as a way of paying for this. And trade union leaders have fully embraced Keynesian policies of ‘deficit financing’ – government borrowing and spending – in order to ‘stimulate growth’.

As Richard Nixon is apocryphally said to have stated in 1971, in response to the collapse of the postwar Bretton Woods monetary arrangement, it seems that “we are all Keynesians now”.

On the other side, a libertarian wing of the capitalist class continues to call for so-called ‘creative destruction’. Pointing to the walking dead of zombie companies and furloughed workers, these reactionary economists and politicians demand that the state’s life support be withdrawn, so that the ‘invisible hand’ of the market can operate freely and ‘efficiently’.

The theoretical basis for this approach can be traced back to the ‘Austrian School’ of economists – the most famous advocate of which was Friedrich Hayek, a contemporary of Keynes.

Much like today, Hayek’s laissez-faire recommendations were largely shunned at the time, in favour of Keynes’ proposal of government stimulus. But the Austrian economist’s ideas were later resurrected by his acolytes in the ‘Chicago School’, who were influential within the Reagan administration, the Thatcher government, and the Pinochet regime.

For decades, these economic doctrines – of Hayekian laissez-faire capitalism and Keynesian state-regulated capitalism – have been presented as the only possible alternatives. This was especially the case after the collapse of the planned economy in the USSR, and the supposed “end-of-history”.

But this dichotomy of ‘the free market and austerity’ vs. ‘government support and growth’ is a false one. These ideas are presented as polar opposites – but in reality they simply represent two ideological wings of the same capitalist class: monetarism and Keynesianism. And neither offers a genuine solution to the crisis – a crisis of capitalism.

For this, we need to look elsewhere, to the revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx. Only these provide a way real forward for workers and youth.

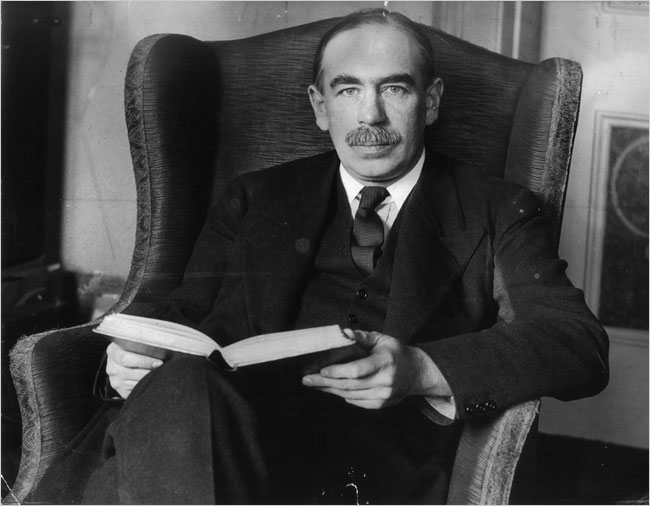

Who was Keynes?

It is ironic that Keynesianism has today become the dominant ideology within the labour movement, as Keynes himself was open about his capitalist class interests, saying that “the class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie”. (JM Keynes, Am I a Liberal?)

It is ironic that Keynesianism has today become the dominant ideology within the labour movement, as Keynes himself was open about his capitalist class interests, saying that “the class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie”. (JM Keynes, Am I a Liberal?)

The Eton and Cambridge educated Englishman was openly opposed to socialism, Bolshevism, and the Russian Revolution. Alongside his career as an academic, he was an economic advisor and lifelong member of the Liberal Party – the classic party of British capitalism in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like all economic and political figures, Keynes was a product of his times; a product of certain historical, material conditions.

Earlier representatives of bourgeois political economy, such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, were the product of a capitalism that was not yet fully developed and was still playing a progressive role. Within the context of this immature capitalism, these ‘classical’ economists could only take the understanding and analysis of the capitalist system so far.

It was only with the further development of capitalism – and the accumulated mass of evidence and experience that went with this development, including the experience of repeated booms and slumps – that Marx was able to uncover the underlying laws and dynamics of capitalism, such as the real processes and relations lying behind value and crisis. As Marx himself explains in Capital:

“In theory, we assume that the laws of the capitalist mode of production develop in their pure form. In reality, this is only an approximation; but the approximation is all the more exact, the more the capitalist mode of production is developed and the less it is adulterated by survivals of earlier economic conditions with which it is amalgamated.” (Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 10)

In many respects, Ricardo was the high point of bourgeois political economy. Marx described those who followed Ricardo as the ‘vulgar’ economists, due to the crude way in which they twisted and turned in their attempts to explain and resolve the contradictions of capitalism without breaking from capitalism itself.

Marx had explained the contradictions within capitalism that led to periodic crises. Any attempts to abolish these contradictions without abolishing capitalism itself were doomed to failure.

Rather than taking political economy forward and developing a greater understanding of capitalism, later economic theorists went backwards. In particular, with the historical development of finance capital and the increasing separation between the owners of capital and the actual production process – a process that Marx had already begun to explain in great detail in Capital (Volume III) – an extremely subjective view of economics emerged.

Known as marginal theory, this individualistic and idealistic economic perspective threw away almost everything useful from the theories of Smith and Ricardo. After all, a consistent materialist analysis based on these ideas inevitably led to the conclusion that capitalism was riddled with contradictions, as Marx himself had concluded.

Instead, therefore, the vulgar economists embraced a one-sided view of capitalism, in which everything was determined by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market and the forces of supply and demand.

These ideas reflected the growing role of banking and speculation – the ‘rentier’ economy in which the bourgeoisie no longer directly owned the means of production and managed their own businesses. Instead, the capitalist class were increasingly simply investors and shareholders, looking to maximise the return on their capital in whatever way possible.

Keynes despised this rentier economy, which he saw as being a great destabiliser of the whole economic system:

“With the separation between ownership and management which prevails to-day and with the development of organised investment markets, a new factor of great importance has entered in, which sometimes facilitates investment but sometimes adds greatly to the instability of the system.”

And later:

“Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation. When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.” (JM Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, chapter 12)

For Keynes, the problem was not capitalism, but simply laissez-faire capitalism, in which unregulated markets and investors were left to pursue their own individual profit without any care for the rest of society.

“For my own part,” the liberal economist stated, “I believe that there is social and psychological justification for significant inequalities of incomes and wealth, but not for such large disparities as exist today.” (ibid, chapter 24)

“For my part,” he wrote elsewhere, “I think that capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable.” (JM Keynes, The End of Laissez-Faire, chapter 5)

In short, Keynes was a utopian, who desired a return to the ‘good old days’, in which the capitalist class were ‘responsible’ industrialists who invested for the good of their communities and society as a whole. In other words, Keynes wanted to turn the wheel of history backwards to an imaginary time of ‘responsible capitalism’.

In this respect, one can see the appeal of Keynes’ ideas to the modern reformist leaders of the labour movement, who have completely accepted capitalism and abandoned any idea of transforming society.

The same phrases are frequently heard today from the mouths of these reformist leaders, who blame ‘neoliberal’, ‘unregulated’, ‘feral’ capitalism for the crisis. But this is the real nature of capitalism as it exists. All attempts to regulate and patch up capitalism – to make this ruthless dog-eat-dog system ‘kind’, ‘green’, or ‘responsible’ – are utopian.

What is Keynesianism?

Keynes’ ideas changed throughout his life in response to the events around him – something he took pride in, famously responding to criticism that his views were inconsistent by saying, “When my information changes, I alter my conclusions. What do you do, sir?”

Keynes’ ideas changed throughout his life in response to the events around him – something he took pride in, famously responding to criticism that his views were inconsistent by saying, “When my information changes, I alter my conclusions. What do you do, sir?”

These days, however, Keynesianism typically refers to the ideas of Keynes in the 1930s; and in particular his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (often referred to simply as the ‘General Theory’), which is the basis for much of modern-day bourgeois macro-economics.

The ideas presented by Keynes in his General Theory were also very much shaped by historical events – in particular by the Great Depression and the scourge of mass unemployment that was seen across the industrialised world at the time, with permanently high rates of unemployment in the region of 10-25%.

Keynes sought to find the answer for this phenomena; and, more importantly, to find a solution.

Previous bourgeois economists had sought to try and justify capitalism theoretically. Such people were mere apologists of capitalism. Keynes, however, painted himself as a ‘pragmatist’, who was no longer simply trying to justify capitalism theoretically, but was trying to save capitalism practically – to save capitalism from itself.

As a member of the “educated bourgeoisie”, Keynes believed that his role, and the role of the state in general, was to intervene in the running of capitalism and to regulate it – not in the interests of ordinary working people, but in the interests of capitalism itself.

The function of state regulation and intervention, in Keynes’ view, was to overcome the contradiction between the interests of various individual capitalists and the interests of the capitalist class as a whole. In other words, Keynes wanted capitalism without its contradictions.

Contradictions and overproduction

This contradiction is at the very heart of capitalism, arising due to the private ownership of the means of production – which in turn means production for profit and competition between different private individuals in pursuit of this profit. This motor force of profit and competition is responsible for both the great historical progressiveness of capitalism in the past, and its great destructiveness in modern times.

Marx and Engels were not blind to the achievements of capitalism. Under capitalism, the competition between individual capitalists in pursuit of profit leads to a large part of this profit (surplus) being continually reinvested in new research and development; new science and technology; and new means of production. All of this is done by the capitalists in order to reduce costs, undercut competitors, and gain a greater market share – and thus greater profits.

In its early days, therefore, capitalism was immensely progressive in its ability to increase productivity, develop the productive capacity of society, and create tremendous amounts of wealth. As Marx and Engels stated in the Communist Manifesto: “[Capitalism] has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals.”

But this process of private ownership and competition contains the seeds of its own destruction. It is in the interest of the individual capitalist to pay their own workers as little as possible in order to maximise profits. However, these wages – and the wages of the workers employed by other capitalists – also form the demand for the commodities that capitalism produces; i.e. the market.

Each individual capitalist would like to pay their workers as little as possible in order to maximise profits. At the same time, however, they would also like their fellow capitalists to pay their workers as much as possible so that these workers can buy the commodities that are being produced.

But each capitalist is trying to do the same thing. Therefore, as individual capitalists compete against one another, trying to maximise their own profits, they cut the wages of the working class as a whole – thus reducing the market and destroying the basis on which they can sell their commodities and realise their profits.

It is this interactive process of competition between many individual capitalists – each making decisions that are completely rational from their own individual perspective – that leads to an overall process that is distinctly irrational for the capitalist class as a whole.

Marx had long ago acknowledged and explained this inherent contradiction within capitalism: the contradiction of overproduction, in which the expansion of production in the pursuit of profit at the same time undercuts the ability for this profit to be realised.

Those who came after Marx – and who tried to find a solution to crises within the limits of capitalism – were forced to ignore him and his ideas as far as possible. Instead, they sought to explain crises by looking at only one side of the problem.

For Keynes, the main problem was the question of demand – or ‘effective demand’ – as he referred to it. For Hayek, the key issue was the question of supply – in particular, the money supply.

Say’s Law

In order to try and explain the phenomena of the Great Depression and mass unemployment, Keynes had to break with many of the established assumptions of his classical predecessors. In this respect, Keynes is attributed with having caused a ‘revolution’ in the field of economics.

In order to try and explain the phenomena of the Great Depression and mass unemployment, Keynes had to break with many of the established assumptions of his classical predecessors. In this respect, Keynes is attributed with having caused a ‘revolution’ in the field of economics.

In reality, there is nothing new in what Keynes said. Indeed, where there is any validity in his writings, the same analysis is expressed far more precisely, clearly, and thoroughly in the works of Marx and Engels. Keynes merely packaged his ideas in a way that was more palatable to the bourgeoisie.

In particular, Keynes attacked what is known as ‘Say’s Law’, attributed to Jean Baptiste Say (although not originally ‘discovered’ by him – a French classical economist of the late 18th / early 19th century.

Say’s Law is commonly referred to in terms of the assertion that supply creates its own demand; that every seller brings a buyer to the market.

Nowadays this same ‘law’ is the basis for the ‘efficient market hypothesis’. This is the theory put forward by the most ardent supporters of the free market, which suggests that, if left to their own devices, market forces – in the ‘long run’ – will allocate resources most effectively, and will always find an ‘equilibrium’, whereby supply meets demand.

But as Keynes was keen to point out in response to his laissez-faire opponents: “In the long run we are all dead.”

Marx disproved Say’s Law long ago. In fact, the existence of periodic crises is all that is needed to disprove Say’s Law.

In Volume II of Capital, Marx explained the accumulation and reproduction of capital that occurs under capitalism by means of a set of schema. In this conceptual model that he outlined, the economy is divided into two sectors: department one, in which the means of production – i.e. capital goods – are produced; and department two, in which consumer goods, for consumption by individual workers (or capitalists), are produced.

Marx showed that in an abstract theoretical sense, Say’s Law is actually true: the economy should be able to achieve equilibrium. But Marx demonstrated that this equilibrium can only be achieved on the basis of the capitalist class continually reinvesting profits into new capital goods – i.e. machinery, buildings, and infrastructure.

On the one hand, this process is what allowed capitalism to play a historically progressive role in the past – developing the productive forces, both qualitatively in terms of new science and technology (and thus increasing productivity); and also quantitatively in terms of its ability to produce a greater total mass of wealth.

On the other hand, this process also contains inherent contradictions. This ‘equilibrium’ is an inherently unstable and temporary one, since the new means of production that are created must be put to work to create a greater mass of commodities; and these, in turn, must find a market – i.e. ‘effective demand’ – in order to be sold and for profit to be realised.

In other words, capitalism can achieve equilibrium in the short term, but only at the expense of creating even greater contradictions in the long term – and thus paving the way for an even larger crisis in the future.

Keynes himself acknowledged this, saying that: “Each time we secure today’s equilibrium by increased investment we are aggravating the difficulty of securing equilibrium tomorrow.” (JM Keynes, The General Theory, chapter 8)

However, unlike Marx, Keynes was not a thorough materialist; nor was he a dialectician. He therefore did not fully draw the conclusions of this statement, as Marx had done many decades earlier – the conclusion that overproduction is an inherent contradiction within capitalism, resulting from the private ownership of the means of production and its drive to produce for profit.

Dialectical materialism

The accumulation and reproduction schemas outlined by Marx in Volume II of Capital are precisely that: schemas; generalised abstractions of a complex process; long-term averages. These averages and equilibria cannot be achieved through a process of slow, smooth, linear change, but only through a dynamic and chaotic process – that is, a dialectical process of contradictions and crises.

The accumulation and reproduction schemas outlined by Marx in Volume II of Capital are precisely that: schemas; generalised abstractions of a complex process; long-term averages. These averages and equilibria cannot be achieved through a process of slow, smooth, linear change, but only through a dynamic and chaotic process – that is, a dialectical process of contradictions and crises.

In other words, these equilibria are in fact dynamic equilibria, constantly being established and then broken, resulting from an infinitely complex process of economic interactions. This is in contrast to the static equilibria conceived of by the supporters of Say’s Law, who imagine the economy as a simple mechanical system, moving along like clockwork.

One could say that Keynes, Hayek, and Marx all had one thing in common: they understood the inherent instability of the capitalist system. But there is also an important difference between Keynes and Hayek, on one side, and Marx, on the other.

As bourgeois economists, imbued with the idealism that permeates society under capitalism, Keynes and Hayek believed that you could distil capitalism or regulate it in order to separate the dynamic elements from this general instability.

By contrast, Marxism, using the method of dialectical materialism, shows how the factors that give rise to capitalism’s initial progressiveness – competition and the reinvestment of profits into new technology and means of production in order to generate even greater profits – are the very same factors that lead to capitalism’s inherent instability.

The key to Marx’s analysis of capitalism lies precisely in the way that this method of dialectical materialism is applied to the field of political economy.

The capitalist system is fundamentally anarchic in nature, due to the individual, private ownership over the means of production and the competition for profit that this entails. This means that changes in the economy can only occur in a dialectical way, thorough crises, rather than in the smooth, gradual way that the proponents of market forces and the ‘invisible hand’ imagine.

The imbalances seen under capitalism are an inherent part of this anarchic system, occurring at every level: between production and consumption; between the different sectors of the economy, and even within particular industries; and between the ever-expanding forces of production and the limits of the market for the commodities resulting from these productive forces.

The only way to rid the system of these imbalances is precisely to eliminate the anarchy of the capitalist system itself. This means overthrowing capitalism, and replacing it with a democratic and socialist plan of production, under the conscious will of society, rather than leaving production up to the blind forces of the market. As Marx explains in Capital:

“Since the aim of capital is not to minister to certain wants, but to produce profit, and since it accomplishes this purpose by methods which adapt the mass of production to the scale of production, not vice versa, a rift must continually ensue between the limited dimensions of consumption under capitalism and a production which forever tends to exceed this immanent barrier. Furthermore, capital consists of commodities, and therefore over-production of capital implies over-production of commodities. Hence the peculiar phenomenon of economists who deny over-production of commodities, admitting over-production of capital. To say that there is no general over-production, but rather a disproportion within the various branches of production, is no more than to say that under capitalist production the proportionality of the individual branches of production springs as a continual process from disproportionality, because the cohesion of the aggregate production imposes itself as a blind law upon the agents of production, and not as a law which, being understood and hence controlled by their common mind, brings the productive process under their joint control.” (Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 15)

The limitations of the classical economists and of the modern day proponents of the free market – the monetarists – lie precisely in their undialectical treatment of the economy.

For these economic theorists, the economy is a simple, mechanical system. Their explanations are either built on the ‘Robinson Crusoe’ model of the economy, in which there exists a single individual on a desert island who is both the only producer and the only consumer; or are based on treating the capitalist system as merely a scaled up version of a barter economy, consisting of the exchange of commodities between individual producers.

In either case, by abstracting the economy to this level of the individual or of simple exchange between individual producers, the bourgeois economists remove all mention of the division of society into classes – and the resultant struggle that arises from this for the surplus produced in society.

Mathematical models – in economics or any other science – are generalised abstractions; approximations of an infinitely complex reality. But modern bourgeois economists think that their equations are the reality, and that the economy must conform to their models. Rather than making their theories fit the facts, the facts are forced to fit the theories.

A similar idealistic tendency is often seen within modern physics, whereby theories are judged according to the ‘beauty’ and simplicity of the equations, rather than by how well they fit the facts and explain actual real life phenomena.

In contrast to this idealistic approach, Marxist economics is based on a dialectical and materialist outlook. Marxism seeks to reach generalised conclusions by looking at the multitude of events and collective historical experience seen under capitalism, and under previous class societies, and drawing out the laws, processes, and tendencies present within the complex system that is the economy.

At all times in his economic writings, however, Marx returns to the fact that the economy is not simply equations and formulas, but a struggle of living forces. The capitalist system is not composed of numbers on a screen, but of ordinary people, made of flesh and blood, trying to put food on the table and a roof over their heads.

Hence, in his magnum opus Capital, Marx alternates between chapters in which he zooms out, abstracts, and provides the general outlines of the process under examination; and others in which he draws upon detailed industrial reports, highlighting how these processes manifest themselves in the workplace – in the real, living struggle between the bosses and the workers.

As Engels points out in his polemic against Dühring:

“…the principles are not the starting-point of the investigation, but its final result; they are not applied to nature and human history, but abstracted from them, it is not nature and the realm of man which conform to these principles, but the principles are only valid in so far as they are in conformity with nature and history. That is the only materialist conception of the matter, and Herr Dühring’s contrary conception is idealistic, makes things stand completely on their heads, and fashions the real world out of ideas, out of schemata, schemes or categories existing somewhere before the world, from eternity — just like a Hegel.” (Engels, Anti-Dühring, chapter 3)

Economics and science

There is, however, also the opposite tendency within bourgeois ideology, which seeks to deny the existence of any laws within capitalism.

There is, however, also the opposite tendency within bourgeois ideology, which seeks to deny the existence of any laws within capitalism.

For these people, including the postmodernists, history and the economy are random processes, beyond the realm of scientific investigation. Such a concept is equally as idealistic as the mechanical view of the classical economists, but arrived at from the opposite direction.

Unlike the vulgar economists who came before them, both Keynes and Hayek sought to turn political economy into a serious science. And yet, both of these bourgeois liberals saw capitalism as a completely unpredictable system, due to its complex and chaotic nature.

Such a view, which is both undialectical and idealistic, is incompatible with a genuine scientific – and Marxist – view, which sees order arising from chaos; predictably arising out of the unpredictable.

Economics, of course, is not an exact science in the same sense as mechanics, due to the complexity of the system involved and the impossibility of isolating this system from the rest of the world. One cannot create repeatable laboratory experiments in the world of economics – although that has not stopped economists such as Milton Friedman of the ‘Chicago School’, an extreme advocate of free markets and laissez-faire capitalism, from trying to create social experiments for their economic theories, such as Pinochet’s Chile.

Nevertheless, by observing the variety of phenomena and processes that occur, and by comparing these against each other in terms of their outcomes, variables, and constants, one can identify the contradictions within the system and formulate laws that describe – and predict – the basic behaviour of the economy at a certain scale.

In this respect, economics is similar to medicine, meteorology, or geology. A doctor cannot always tell you exactly what disease you have or at what point death will occur; nor can weather forecasters or seismologists tell you exactly what the weather will be like next month or when the next earthquake will hit. Nevertheless, doctors, meteorologists, and seismologists can all make predictions –and often very accurate ones – at a certain scale; and the accuracy of these predictions is continually increasing as scientific understanding improves on the basis of experience and investigation.

An analogy can be drawn with that of thermodynamics. The behaviour of an individual, isolated gas molecule can be described using Newtonian mechanics. However, the behaviour of this individual particle becomes unpredictable as soon as we now examine a container of many hundreds or thousands of gas molecules, all interacting with one another.

Nevertheless, out of this incredibly complex system, one can still draw simple, generalised laws that describe the behaviour of the volume of gas as a whole, including properties such as the temperature and pressure of the gas. From complexity arises simplicity; out of chaos arises order.

Similarly, whilst one cannot predict the exact course of an individual’s life, at the scale of society as a whole, generalised laws can be drawn and predictions can be made: the economic laws of capitalist crisis; and the historical laws of the development of productive forces, class struggle, and revolution.

Ultimately, however, these generalised laws and economic theories, abstracted from this historical experience and investigation, must be applied to the concrete conditions facing us, in order to gain a proper understanding of any given situation. And these conditions include a whole host of political factors.

It should never be forgotten that the economy is not a simple mechanical system that can be represented by abstractions and equations; it is a battle of living, breathing forces. Ultimately, therefore, it is the balance of class forces that is decisive when it comes to determining the outcome of the economy.

It is to the credit of Keynes and Hayek that they, like Marx, sought to treat economics as a science, looking for the laws that governed the economy by a careful study of the facts. However, unlike Marx, neither Keynes nor Hayek were thorough materialists, nor were they dialecticians.

As a result, their theoretical explanations frequently fall into the traps outlined above: either of idealism, only looking at one side of a many-sided, complex problem, and thus failing to provide a material explanation for phenomena; or of mechanical materialism, seeking to explain the economy as a simple clockwork system, devoid of politics, where cause and effect are linear, acting in only one direction.

The General Theory

Keynes equally despised the idealistic and dogmatic nature of his contemporary bourgeois economists. Faced with the crisis of the Great Depression and the clear failure of the free market, his laissez-faire opponents refused to abandon their assumptions, including those of Say’s Law, and their faith in the invisible hand. In his criticism of the classical economists, Keynes said that:

Keynes equally despised the idealistic and dogmatic nature of his contemporary bourgeois economists. Faced with the crisis of the Great Depression and the clear failure of the free market, his laissez-faire opponents refused to abandon their assumptions, including those of Say’s Law, and their faith in the invisible hand. In his criticism of the classical economists, Keynes said that:

“[W]riters in the classical tradition, overlooking the special assumption underlying their theory, have been driven inevitably to the conclusion, perfectly logical on their assumption, that apparent unemployment (apart from the admitted exceptions) must be due at bottom to a refusal by the unemployed factors to accept a reward which corresponds to their marginal productivity…

“…The classical theorists resemble Euclidean geometers in a non-Euclidean world who, discovering that in experience straight lines apparently parallel often meet, rebuke the lines for not keeping straight as the only remedy for the unfortunate collisions which are occurring. Yet, in truth, there is no remedy except to throw over the axiom of parallels and to work out a non-Euclidean geometry. Something similar is required today in economics.”

(JM Keynes, The General Theory, chapter 2)

Many of Keynes’ peers in the political and economic community sought ‘supply side’ solutions to the problems of mass unemployment and recession – that is, eliminating barriers to the free market, such as trade unions, which in the view of these economists restrict the ability for the market to find the ‘natural equilibrium’ for wages.

In response, however, Keynes bent the stick in the opposite direction and simply focused on the question of demand; or ‘effective demand’ as he referred to it – the ability for the producers of commodities to find a willing buyer who is able to pay. This is in contrast to ‘demand’ in the sense of the ‘needs’ or ‘wants’ in society.

Keynes explained that the crisis of the Great Depression was a vicious circle: high unemployment resulted in a reduced effective demand for commodities; this led businesses to scale back or shut down; and this increased unemployment further.

In such a situation, Keynes believed government stimulus was necessary to provide a boost to effective demand. In this way, the English economist asserted, the vicious circle could be transformed into a virtuous one, with increasing demand from the government leading to an expansion of production and employment, and thus greater wages and greater demand for consumer goods, etc. etc.

For Keynes, any stimulus would be sufficient. As he wryly comments in his General Theory:

“Pyramid-building, earthquakes, even wars may serve to increase wealth, if the education of our statesmen on the principles of the classical economics stands in the way of anything better…

“…If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.”

(JM Keynes, The General Theory, chapter 10)

The New Deal in 1930s America is often cited as the success story of Keynesian policies. In reality, however, it was only the militarisation of the economy during the Second World War that ended the Great Depression – a process that ended in millions of deaths, the destruction of vast amounts of society’s productive capacity, and a public debt of over 200% of GDP in countries like Britain. Hardly a success!

Even Keynes himself was forced to admit defeat and acknowledge the limitations of his proposals, writing: “It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case — except in war conditions.”

Under-consumption and overproduction

In essence, the Keynesian explanation of crisis is a theory of ‘under-consumption’. In other words, the crisis is blamed on a lack of consumer demand for the commodities that are produced.

In essence, the Keynesian explanation of crisis is a theory of ‘under-consumption’. In other words, the crisis is blamed on a lack of consumer demand for the commodities that are produced.

Marxism, by contrast, sees capitalist crisis as a crisis of ‘overproduction’. The difference is the understanding that capitalism is inherently unable to find a market for all the commodities that are produced.

This arises from the fact that capitalism is production for profit; and this profit is simply the unpaid labour of the working class. In other words, the working class is always paid back less in wages than the value it creates in the labour process. Workers’ ability to buy back the commodities they produce is therefore always less than the total value of these commodities. Commodities are produced but cannot be sold; profit cannot be realised; production ceases; the system enters into crisis.

The Keynesian idea of creating demand through government stimulus is ultimately idealistic and undialectical. The simple question must be asked: where does the government get the money from for this stimulus?

If the money is to come from taxes, then this will either mean: taxing the capitalist class, which means biting into their profits, creating a strike of capital and thus reducing investment; or taxing the working class, which will reduce their consuming power and thus reduce demand – the opposite of what government stimulus is intended to do!

Recently, governments worldwide have increasingly resorted to borrowing money from the financial markets, through the selling of government bonds. But this ‘deficit financing’ results in large public debts. And there is no such thing as a free lunch. These debts must eventually be paid back – with interest.

Similarly, the move towards ‘monetary financing’ – central banks funding government spending by expanding the money supply, as seen in recent years with Quantitative Easing – is equally fraught with problems.

At the end of the day, it is not a lack of money that stops the capitalists from investing, but the lack of profitable markets. As long as ‘excess capacity’ – that is, overproduction – exists within the world economy, the capitalists will not invest. Instead, the extra money injected into the system will simply inflate speculative bubbles and add to the volatility of frothy stock markets.

In either case, the point is clear: the intervention of the state cannot resolve the contradictions of capitalism – neither through government stimulus, nor through printing money.

For the Keynesians, and the reformist leaders of the labour movement that are inspired by Keynesian ideas, the answer is simple: we must tax the rich and increase wages! But under capitalism, as explained above, production is for profit, and the working class can never receive in wages the full value of the commodities they produce. As Marx explained in Capital in response to the under-consumptionist theories of his day:

“It is sheer tautology to say that crises are caused by the scarcity of effective consumption, or of effective consumers. The capitalist system does not know any other modes of consumption than effective ones, except that of sub forma pauperis or of the swindler. That commodities are unsaleable means only that no effective purchasers have been found for them, i.e. consumers (since commodities are bought in the final analysis for productive or individual consumption). But if one were to attempt to give this tautology the semblance of a profounder justification by saying that the working-class receives too small a portion of its own product and the evil would be remedied as soon as it receives a larger share of it and its wages increase in consequence, one could only remark that crises are always prepared by precisely a period in which wages rise generally and the working-class actually gets a larger share of that part of the annual product which is intended for consumption. From the point of view of these advocates of sound and “simple” (!) common sense, such a period should rather remove the crisis. It appears, then, that capitalist production comprises conditions independent of good or bad will, conditions which permit the working-class to enjoy that relative prosperity only momentarily, and at that always only as the harbinger of a coming crisis.”

(Marx, Capital, Volume II, chapter 20)

The Keynesian explanation for crisis is, in reality, not really an explanation for the cause of capitalist crisis at all. At best, it is an explanation for the continuation or deepening of a crisis in the economy that already exists; or a suggestion for how governments can try to escape a crisis within the confines of capitalism.

If a lack of effective demand – i.e. under-consumption – is to be blamed for the crisis, then one must surely ask: What leads to this under-consumption in the first place? Why is there spare productive capacity in the system that is lying idle? Why must the government step in to ‘stimulate demand’?

As Engels points out in his polemic against Dühring:

“[T]he under-consumption of the masses, the restriction of the consumption of the masses to what is necessary for their maintenance and reproduction, is not a new phenomenon. It has existed as long as there have been exploiting and exploited classes…

“…The under-consumption of the masses is a necessary condition of all forms of society based on exploitation, consequently also of the capitalist form; but it is the capitalist form of production which first gives rise to crises. The under-consumption of the masses is therefore also a prerequisite condition of crises, and plays in them a role which has long been recognised. But it tells us just as little why crises exist today as why they did not exist before.” (Engels, Anti-Dühring, Part III, chapter 3)

In other words, since the working class can never buy back all of the commodities that they produce, why is capitalism not always in crisis?

Historically, this contradiction of overproduction has been overcome through the role of investment, with profits reinvested in new means of production – on research and new machinery – in order to improve productivity, drive down costs, gain a greater market share, and increase profits even further. As explained earlier, it is this investment, arising from competition and the pursuit of profits, that allowed capitalism to play a historically progressive role in developing the means of production.

But as was also explained earlier, this reinvestment of profits, rather than resolving the contradiction of overproduction and restoring economic equilibrium, only creates even greater productive forces. Ever greater quantities of commodities and values are then produced. And these must still be sold on an ever-restricted market – thus exacerbating the contradictions and preparing the way for a larger crisis in the future.

Unproductive investment – such as the earlier example given by Keynes of burying old bottles filled with banknotes – has also been used in the past in order to provide demand and create jobs. For example, there were some so-called Marxists during the post-war boom who believed that military spending by governments could be used to permanently avert a crisis.

But as has been pointed out, governments cannot simply ‘create’ demand. In reality, state expenditure comes from taking a slice of wealth from either the capitalist class or from the working class.

Unproductive investment is spending without producing any real value. This acts as ‘fictitious capital’, increasing the circulation of money in the economy without generating an equivalent value that is also in circulation. This is a recipe for generating inflation.

This is exactly what was seen at the end of the post-war boom, whereby Keynesian policies led to the crisis of the 1970s, in which economic stagnation was seen alongside rising inflation – a previously unseen phenomena known as ‘stagflation’. And there is the potential for the same to occur today, as trillions in government stimulus and newly-printed money clashes up against the barrier of overproduction and mass unemployment.

All of this again shows the undialectical and mechanical nature of Keynesianism and other reformist solutions to crises, which do not follow through the implications of their suggestions to their logical conclusion.

If investment is used to avert a crisis, this means investing in something material – that is, in means of production, which must then produce further commodities, thus adding to the crisis of overproduction.

And if wages are to be increased in order to increase demand, this means biting into the profits of the capitalists. But this, in turn, reduces investment, which under capitalism is only conducted in order to make a profit. If demand is to be ‘created’ through government stimulus, this, in reality, means either taking money from the capitalists and biting into profits; or taking money from the working class and biting into consumer demand.

In contrast to bourgeois economics, Marxism seeks to examine the economy dialectically. That is to say, Marxism seeks to explore the full implications of any action; to see the interconnectivity and feedback between different processes and phenomena; to examine the system in its motion and in all its complexity.

Marxist economics is about seeing the contradictions within the processes at play, and to show how these contradictions can always be resolved, but only by creating new contradictions in the process. This is the case with capitalism: a crisis can always be averted temporarily, but this only serves to heighten the contradictions and pave the way for a greater crisis in the future.

In addition, unlike the bourgeois economists, Marxists do not separate their economic analysis from their general analysis of society. The economy is made up of living, breathing human beings. As Lenin stated, “politics is concentrated economics”. The ruling class can always restore stability in the economy, but only at the expense of creating political instability and class struggle in society.

In the final analysis, the crisis of capitalism is not simply the result of this or not process; this or that contradiction. Crises are the result of the many interacting processes and contradictions within capitalism itself. As Marx says in Capital:

“Capitalist production seeks continually to overcome these immanent barriers, but overcomes them only by means which again place these barriers in its way and on a more formidable scale.

“The real barrier of capitalist production is capital itself. It is that capital and its self-expansion appear as the starting and the closing point, the motive and the purpose of production; that production is only production for capital and not vice versa, the means of production are not mere means for a constant expansion of the living process of the society of producers. The limits within which the preservation and self-expansion of the value of capital resting on the expropriation and pauperisation of the great mass of producers can alone move — these limits come continually into conflict with the methods of production employed by capital for its purposes, which drive towards unlimited extension of production, towards production as an end in itself, towards unconditional development of the social productivity of labour. The means — unconditional development of the productive forces of society — comes continually into conflict with the limited purpose, the self-expansion of the existing capital. The capitalist mode of production is, for this reason, a historical means of developing the material forces of production and creating an appropriate world-market and is, at the same time, a continual conflict between this its historical task and its own corresponding relations of social production.”

(Capital, Volume III, chapter 15; Marx)

Keynes, profit, and investment

In some respect, Keynes was able to recognise the interconnectivity of the capitalist system. He did note what he referred to as the ‘paradox of thrift’: that one capitalist’s wage costs are another capitalist’s market; and therefore what may be rational and necessary for one capitalist – to cut wage costs – is not necessarily rational for the capitalists as a whole.

In some respect, Keynes was able to recognise the interconnectivity of the capitalist system. He did note what he referred to as the ‘paradox of thrift’: that one capitalist’s wage costs are another capitalist’s market; and therefore what may be rational and necessary for one capitalist – to cut wage costs – is not necessarily rational for the capitalists as a whole.

Vitally, however, Keynes did not see the interconnected relationship between wages and profits: that these were two sides of the same coin, both merely representing a divided proportion of the total value created by the working class through the application of labour; and that increasing one necessitated cutting the other, and vice-versa.

Hence the inability of Keynesians to see that overcoming ‘under-consumption’ – i.e. overcoming the lack of effective demand – through increasing wages or government stimulus can only create new contradictions by reducing profits for the capitalists, leading to a strike of capital and reduction in investment.

Keynes defined the total demand in society (also known as the ‘aggregate demand’ in macroeconomics) as being equal to the total income, which is also equal to the total output. This aggregate demand is composed primarily of two sources according to Keynes: consumption from households, and investment by firms.

This definition is similar to Marx’s two departments, defined in Capital Volume II, of production of capital goods (department one) and production of consumer goods (department two). Unlike Marx, however, Keynes did not then subdivide these two departments into their various components of value: constant, variable, and surplus.

Throughout Capital, Marx frequently highlights the need to examine the economy in its totality, rather than simply isolating specific aspects of the system, or concentrating on the behaviour of single individuals and transactions.

However, Marx also highlighted the dialectical interaction between opposites within this totality: between labour and capital; between wages and profits; between department one and department two. And he showed how these interactions – along with the patterns that emerged from the anarchic and chaotic (and yet rational) actions of many different individual capitalists – were key to understanding the dynamic and crisis-ridden nature of capitalism.

As mentioned earlier, the classical economists who preceded Marx were unable to understand the origin of profit. This is because of how they treated the economy: either as a ‘Robinson Crusoe’, desert island system, in which one man was both producer and consumer; or as a simple transaction between one buyer and one seller, whereby profits were simply created in the process of circulation by buying cheap and selling dear. In both cases, by reducing the economy to an individual or pair of individuals, the division of society into classes is lost.

By contrast, Keynesianism, on which modern macroeconomics is based, arrives at a similar result to the pre-Marxist classical economists, but from the opposite direction. By simply aggregating the economy into a single equation or schema of total demand, Keynesianism loses sight of the class struggle and the interconnectivity between wages and profits. In fact, Keynesianism often ends up ignoring the role of profit altogether.

One can see the mechanical nature of the Keynesian schema by the example of the ‘Phillips machine’ or ‘MONIAC’: a physical model of the economy based on Keynesian macroeconomic principles, which uses water storage and flows to represent the stores and flow of capital and money, and which is supposed to be able to predict the behaviour of the real economy on this basis.

As a result of this aggregated, undialectical, mechanical view, Keynesianism and modern macroeconomics cannot explain the material basis behind investment under capitalism.

At its best, bourgeois macroeconomics describes investment as being a function of the interest rate, with lower interest rates providing an incentive for investors to spend rather than save. But at the current time, interest rates are almost at zero percent, or are even negative in some cases; and yet there is no investment to be seen.

At its worst, business investment is idealistically explained by Keynes and Keynesians with reference to ‘animal spirits’. These days, a similarly idealistic explanation for investment is given in terms of the need for ‘business confidence’.

Resorting to ‘animal spirits’ and ‘confidence’ clearly explains nothing. One must ask: what then causes confidence? The argument given in response is typically of a circular nature: businesses invest if there is confidence; there is confidence if the economy is growing; there is economic growth if there is investment; and so on and so on.

Whilst it is true that confidence, uncertainty, and risk play a role in determining the decisions of investors, this confidence and uncertainty must have a material basis. Under capitalism, investment is made in pursuit of profit. If commodities cannot be sold at a profit – or indeed sold at all, as is the case with the current crisis of overproduction – then production, and investment in new production, will not occur.

It is not a subjective lack of confidence that causes the crisis, but the objective crisis of capitalism that causes a lack of confidence. As has been seen on numerous occasions in the recent period, there have been frequent rallies of the stock market in response to the latest ‘plan’ by politicians to ‘solve’ the crisis. But these rallies are always short lived, going up like a rocket and coming down like a stick, as the contradictions reappear and the next phase of the crisis emerges on the horizon.

These days, rather than invest in new means of production, which must produce new commodities that must find a market and be sold, the capitalists can see that there is a chronic over-capacity in the system. They are instead choosing to spend their money on speculative purchases; or in buying up existing companies – i.e. existing means of production.

This process leads to concentration of capital, but without creating any new value. Instead of being used to develop the means of production and provide socially necessary goods and services, the hoard of wealth that has been amassed by the capitalist class is being squandered.

Hayek, credit, and the crisis

Unlike Keynes, who saw the problem as one of effective demand during the crisis, Hayek saw the problem as one of loose monetary policy in the period before the crisis. In particular, Hayek argued that it is government interference in the money supply – for example, through setting low interest rates, printing too much money, and encouraging the expansion of credit – that creates bubbles and distorts the market. This, in turn, leads to crises when these bubbles burst and the boom is seen to be largely based on fictitious capital.

Unlike Keynes, who saw the problem as one of effective demand during the crisis, Hayek saw the problem as one of loose monetary policy in the period before the crisis. In particular, Hayek argued that it is government interference in the money supply – for example, through setting low interest rates, printing too much money, and encouraging the expansion of credit – that creates bubbles and distorts the market. This, in turn, leads to crises when these bubbles burst and the boom is seen to be largely based on fictitious capital.

Like Keynes, Hayek only saw one side of the problem – that of supply, as opposed to Keynes and the question of demand. And also like Keynes, Hayek did not follow through his analysis to its logical conclusion and ask the obvious question: What would happen if governments never intervened by setting low interest rates and encouraging the expansion of credit?

First, however, one must ask the even more simple question of: What is credit?

Marx explains the role of credit under capitalism in Capital, explaining that credit serves a dual function. On the one hand, relatively short-term credit is required to overcome bottlenecks in production and maintain the flow and circulation of capital.

For example, businesses need to borrow money to pay for wages and raw materials whilst they wait for previously produced goods to reach the market and be sold. Alternatively, credit may be used to allow firms to expand production when they don’t have the upfront capital to pay for it.

On the other hand, credit also plays the role of artificially expanding the market – i.e. effective demand – and thus helping to delay a crisis.

As explained earlier, under capitalism, the working class can never buy back the full value of the commodities it creates, due to the fundamental nature of capitalism as production for profit. As was also explained earlier, capitalism traditionally overcomes this contradiction of overproduction by reinvesting the surplus value created into new means of production in the search for greater profits.

This, however, only serves to create even greater productive forces, and thus an even greater mass of commodities that must find a market. Rather than resolving the contradiction, therefore, this only exacerbates overproduction.

Credit provided by the banks is formed from the concentrated savings and deposits of individuals and firms. This is used to artificially increase the consumptive capacity of the masses, and thus to temporarily overcome overproduction, allowing the productive forces to continue expanding.

In the run-up to the crash of 2007-08, the expansion of credit created the largest credit bubble in history. This was the primary factor in delaying the onset of a crisis. But it ended up paving the way for an even greater explosion when the day of reckoning eventually arrived.

This expansion of credit was required to overcome the growing proportion of wealth going to capital rather than labour. This became increasingly unequal with the attacks on the working class that followed the crisis of the 1970s, and which continued in the 80s with the policies of Reagan, Thatcher, and the other political representatives of capitalism.

This ever increasing exploitation of the working class continued into the 90s and the 21st century though the intensification of the working week and the increase in overtime; through attacks on wages and conditions; and with many workers being forced to take two jobs in order to just get by. Alongside this increasing exploitation, credit was massively expanded through the use of mortgages, credit cards, student loans, etc.

Hayek’s ideas contain an element of truth in saying that the expansion of credit causes crises. In reality, however, the expansion of credit does not cause the crisis. Rather, it delays the crisis by artificially expanding the market in the short term, at the expense of exacerbating the problem of overproduction, leading to an even bigger crisis in the future.

Similarly, low interest rates were used to fuel the boom beyond its limits by encouraging investment and consumer spending – consumption that was, again, reliant on credit.

The expansion of credit, however, is a dialectical process. The expansion of credit allows the productive forces to grow; and the growth of the productive forces fuels the expansion of credit. As Marx explains:

“Credit is, therefore, indispensable here; credit, whose volume grows with the growing volume of value of production and whose time duration grows with the increasing distance of the markets. A mutual interaction takes place here. The development of the production process extends the credit, and credit leads to an extension of industrial and commercial operations.” (Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 30)

During the boom, nobody questions this seemingly virtuous circle. The bourgeoisie are filled with a sense of optimism. All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

But as with all dialectical processes, at a certain point there must be a transformation from quantity into quality. The vast lending of credit on one side appears now as a tremendous pile of debts on the other; the restricted consumption of the masses is once again apparent; and the limits of the productive forces to expand reassert themselves. Overproduction is evident and crisis breaks out.

As Marx explains, this overproduction is, in the final analysis, the cause of the crisis:

“The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses as opposed to the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as though only the absolute consuming power of society constituted their limit.”

(Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 30)

Marx also long ago answered those who claim that it is the drying up of credit – familiarly known today as a ‘credit crunch’ – that causes crises. He pointed out that it is, in fact, not the lack of credit that is responsible for the crisis, but the crisis that leads to a lack of credit:

“As long as the reproduction process is continuous and, therefore, the return flow assured, this credit exists and expands, and its expansion is based upon the expansion of the reproduction process itself. As soon as a stoppage takes place, as a result of delayed returns, glutted markets, or fallen prices, a superabundance of industrial capital becomes available, but in a form in which it cannot perform its functions. A great deal of commodity capital, but unsaleable. A great deal of fixed capital, but largely idle due to stagnant reproduction. Credit is contracted 1) because this capital is idle, i.e., blocked in one of its phases of reproduction because it cannot complete its metamorphosis; 2) because confidence in the continuity of the reproduction process has been shaken; 3) because the demand for this commercial credit diminishes…

“…Hence, if there is a disturbance in this expansion or even in the normal flow of the reproduction process, credit also becomes scarce; it is more difficult to obtain commodities on credit. However, the demand for cash payment and the caution observed toward sales on credit are particularly characteristic of the phase of the industrial cycle following a crash…

“…Factories are closed, raw materials accumulate, finished products flood the market as commodities.”

(Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 30)

It is, therefore, neither the expansion of the credit during the boom, nor the contraction of credit, that is responsible for the crisis. The expansion of credit merely delays the crisis of overproduction. And the contraction of credit is simply a qualitative manifestation of this very same overproduction.

To return to Hayek and the original question that the Hayekians do not consider: What would happen if governments were not to intervene in the economy and credit was not expanded? Would crises be avoided by the magical invisible hand of the market?

The modern day Hayekians imagine that without government interference, the market forces of supply and demand, with their accompanying price signals, would solve all problems; that a crisis might still occur, but that this would constitute a minor blip in comparison to the deep and painful slump that society has experienced as a consequence of the 2008 crash.

But as we have explained above, credit does not create a crisis; rather, it merely delays it. In the absence of the expansion of credit, the crisis of the 1970’s would simply have continued and developed onto a new plane.

The expansion of credit was required to maintain the consumptive capacity of the working class in the face of attacks on the wages – i.e. the purchasing power – of these very same workers, all in the name of maintaining profits for the capitalists.

Without the expansion of credit, the expansion of the productive forces would have been met with a limited market (a lack of effective demand) at a much earlier date. Companies would have ceased to expand production in the face of a falling demand for consumer goods; unemployment would have risen; the vicious cycle of recession would have set in.

Rather than finding a stable equilibrium, the solution of the Hayekians – to remove any interference in the market and to allow the money supply to regulate itself – would simply lead to an increasingly volatile and turbulent system; to an economy that spirals out of control; to a situation that resembles that of the current period.

Once again we see that the fault of the Hayekians, as with the Keynesians, is their focus on only one side of a many sided problem. In trying to resolve one contradiction, the capitalists merely create new contradictions elsewhere on a bigger scale.

In reality, despite his unbridled faith in the free market, Hayek was never really accepted by the political representatives of capitalism, who could not swallow his creed that there should be no government interference in the economy at all.

In the face of crisis, bourgeois politicians have always buckled, throwing all talk of the ‘free market’ out of the window, and instead doing whatever it takes to save capitalism from its own contradictions.

Hence we see how the ruling class, in periods of deep crisis such as now, are willing to swallow their Keynesian medicine. They fear the social consequences of completely withdrawing the state’s support; the mass unemployment and potential revolutionary explosions that would result if society’s fate was left to the invisible hand of the market.

Like Keynes himself, therefore, when their system is faced with an existential threat, the ruling class see the necessity for the state to intervene in the running and regulation of capitalism.

Exports, imports, and trade imbalances

Modern macroeconomics – based on Keynes’ ideas in the General Theory – cite four main sources of output, demand, and growth for a national economy: consumption; investment; government spending; and exports.

Modern macroeconomics – based on Keynes’ ideas in the General Theory – cite four main sources of output, demand, and growth for a national economy: consumption; investment; government spending; and exports.

In ‘normal’ times, a contraction of one section would hopefully be compensated for by another. But in the current era, all four of these sectors are held back.

In the short term, consumption may get a temporary boost, as the ‘pent-up demand’ of household savings is spent – e.g. on retail, hospitality, and tourism. But in the long run, consumption will be held back by low wages, alongside a hangover of private debt.

Similarly with government spending. At present, this is in overdrive, with capitalist politicians using the state to prop up global markets through unprecedented fiscal stimulus.

This state-led splurge, however, finds its counterpart in an eye-watering level of public debt. In total, as mentioned earlier, global public debt now stands at an estimated 100% of GDP. In other words, even if all of society’s economic resources were dedicated to paying off the debt and nothing else, this goal would take a year to achieve.

Looking at governments, companies, and households together, the estimated total debt globally – public and private – now stands at an all-time high of $281 trillion, or 355% of world GDP.

Eventually the bill will be presented for all of this debt, which means further austerity and cuts down the line. This will drag on government spending and household consumption for years, if not decades, to come.

Investment, meanwhile, is also held back, with capitalists unwilling to invest in new production when there is already excess capacity – i.e. overproduction – across the board.

Finally, therefore, we are left with exports. But it is a basic truism that not every country can be a net-exporter. For every export that must be an equivalent value of imports; or there will be a flow of exports from one country and an accumulation of debt elsewhere.

Each nation’s politicians promise to export their way out of the crisis. In an ideal world they would like to do this by making their country’s exports more competitive by holding wages down, whilst simultaneously hoping that every other country increases their imports by paying their workers more. But every country’s capitalists and political representatives are attempting to do the same thing.

Hence we arrive at the general pattern of overproduction, but now seen on an international scale, with competition between the capitalists of different nations leading to wages being cut across the board, demand falling, and the market shrinking.

We see this today reflected in the calls by the Keynesian commentators of various countries, who exclaim that “we must be more like Germany and China!”; “we must invest, be more competitive, and export!”

But not everyone can be like Germany and China. One only needs to ask the simple question of: Export to whom? In an age of austerity, where is there the demand for increased imports?

Hence the calls by politicians and political commentators for Germany and China to ‘rebalance’ their economies – that is, to increase wages, thus reducing the competitiveness of exports and providing the means for greater consumption of imports. But why would the bourgeoisie in Germany and China want to do this when they are doing very well out of the current situation?

In reality, such attempts by countries to export their way out of a crisis only lead to a race to the bottom; to trade wars, increasing protectionism, and to an exacerbation of the crisis for all.

Keynes, in fact, understood the dangers of large trade imbalances in a global economy. He was therefore keen to see an agreement within the post-war Bretton Woods system that would limit imbalances between countries. But he was overruled by US negotiators, who instead imposed a setup that would benefit American capitalism, which at the time registered a big trade surplus.

In a world where every economy is linked to every other by a thousand threads, crisis in one country affects all. We therefore end up in the situation today, with a crisis of capitalism that is truly global – and not just because of the pandemic.

As we have pointed out elsewhere, China’s economy is no longer predominantly export-led. Instead, since 2008, the Chinese government has been forced to embark on one of the largest Keynesian experiments in history, pouring government spending into housing, infrastructure, and new means of production.

But like all Keynesian experiments, this is building up enormous levels of debt, on the one side; and is increasing productive capacity, on the other, preparing the way for an even greater crisis of overproduction in the future.

At its root, trade imbalances – with deficits at one end and surpluses at the other – are not the cause of the crisis, but are yet another manifestation of it. The huge trade deficits of some countries are just the other side of the coin to the trade surpluses in others.

In net-exporting countries such as Germany and China, wages have been held down whilst the productive forces have expanded. The commodities produced cannot be sold at home, and must therefore find a market abroad. The vast wealth of German and Chinese exports are, therefore, simply an expression of the equally vast overproduction that exists within these countries.

Marx understood and explained this in Capital:

“It should be noted in regard to imports and exports, that, one after another, all countries become involved in a crisis and that it then becomes evident that all of them, with few exceptions, have exported and imported too much, so that they all have an unfavourable balance of payments. The trouble, therefore, does not actually lie with the balance of payments…

“Now comes the turn of some other country. The balance of payments was momentarily in its favour; but now the time lapse normally existing between the balance of payments and balance of trade has been eliminated or at least reduced by the crisis: all payments are now suddenly supposed to be made at once. The same thing is now repeated here… What appears in one country as excessive imports, appears in the other as excessive exports, and vice versa. But over-imports and over-exports have taken place in all countries… that is overproduction promoted by credit and the general inflation of prices that goes with it…

“The balance of payments is in times of general crisis unfavourable to every nation, at least to every commercially developed nation, but always to each country in succession, as in volley firing, i.e., as soon as each one’s turn comes for making payments; and once the crisis has broken out… It then becomes evident that all these nations have simultaneously over-exported (thus over-produced) and over-imported (thus over-traded), that prices were inflated in all of them, and credit stretched too far. And the same break-down takes place in all of them. The phenomenon of a gold drain then takes place successively in all of them and proves precisely by its general character: (1) that gold drain is just a phenomenon of a crisis, not its cause; (2) that the sequence in which it hits the various countries indicates only when their judgement-day has come, i.e., when the crisis started and its latent elements come to the fore there.”

(Marx, Capital, Volume III, chapter 30; Emphasis in the original)

In regards to weaker economies, bourgeois commentators often refer to the problem as one simply of ‘competitiveness’. But as we have explained above regarding imports, exports, and trade imbalances, international competitiveness is fundamentally no different from the competition between different capitalist firms: under capitalism there will always be winners and losers. Not everyone can be the most competitive. Competition is always relative.

The main difference is that in the competition between firms, weak firms will go under and will be subsumed by the stronger ones; on the international plane, less competitive national economies cannot be so simply assimilated – although that, in essence, is the proposal for a fiscal union inside the Eurozone: for a single economic zone in which the weaker economies are placed under the direct control of the stronger ones – i.e. of German capitalism.

But as with the competition between capitalist firms, the competition between capitalist nations is ultimately a race to the bottom in which the capitalists are cutting away at the very branch they are sitting on.

In trying to gain competitiveness the capitalists must either cut the wages of the working class, and thus cut into the market for the commodities that are produced; or they must invest in productivity and thus expand the productive forces. In either case, the crisis of overproduction is exacerbated.

Again, what makes sense from the perspective of a single national capitalism – to cut wages, increase productivity, gain competitiveness, and export abroad – is ultimately destructive for the international economy as a whole.

This, once again, demonstrates the fundamental barriers to the growth of the productive forces: the private ownership of the means of production and the nation state – both of which have become the most monstrous of fetters on the development of science, technology, culture, and society in general.

Need for socialism