Recent weeks have seen Ireland bear witness to two factory occupations that subsequently inspired similar actions across Britain. These events are significant developments in class struggle in that they pose the question of whether power resides with the boss or the workers.

It is fitting that these events should coincide with the ninetieth anniversary of the Limerick Soviet. The events that took place in the small Munster town during April 1919 have all too predictably been written out of the official history of Ireland. They have also been largely forgotten in the labour movement due to the role of a conservative bureaucratic leadership that has sought to bury the history of the Irish working class’s most potent challenge to capitalist rule.

As at present, 1919 was a time when capitalism was engrossed in an international crisis following the end of the First World War. Europe was in revolutionary ferment following the Russian Revolution with revolts brewing in Germany, France, Italy, and Britain.

In Ireland this also coincided with the development of the national liberation struggle. The 1918 elections had seen the constitutional Irish National Party swept aside by Sinn Fein, which was supported by the trade unions and the Labour Party.

The seventy three Sinn Fein MPs, a majority of the total one hundred and five from Ireland, met as the secessionist Dail Eireann on 21 January 1919. Only twenty six of the MPs were present as the rest were languishing in prison.

The Dail declared that “a state of war existed”, that could not end “until Ireland is definitely evacuated by the armed forces of England”. This came alongside the killing of two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers by an IRA unit and marked the beginning of the Irish War of Independence.

Class struggle

It would be wrong to look at this period in Irish history as purely one of struggle taking place on a nationalist plane.

Although the working class had experienced defeat in Ireland following the Dublin lockout in 1913 and the onset of war the following year with the addition of the suppression of the Irish Citizens Army and Connolly’s execution in 1916, by 1918 the tempo of struggle was increasing

Plans to introduce conscription in Ireland were withdrawn after a general strike organised by the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) on April 23rd 1918.

The end of the war saw Ireland engulfed by further strike action, including a month long strike for the forty hour week in Belfast, during which twenty six different unions coordinating action by more than forty thousand workers.

Limerick was not unaffected by these developments, seeing demonstrations against conscription in April 1918 and a May Day march of some ten to fifteen thousand, in a town of only forty thousand people, pass a resolution in solidarity with the Russian Revolution.

Following its establishment in 1909 the ITGWU had declared, “”The days of the local society are dead; the day of the Craft Union is passing; the day for the One Big Union has come”.

In Limerick the ITGWU’s first success was the unionisation of the 600 workers of the town’s biggest employer, the Cleeve’s creamery. By 1918 the IGTWU had three thousand members in Limerick. These workers proved to be the back bone of the struggle around the Soviet.

On January 13th 1919 the local postal worker and member of the Irish Volunteers, Robert Byrne was arrested and charged with possession of a revolver and ammunition. Byrne was also a member of the Limerick Trades Council and had been sacked from his job days before for attending the funeral of another volunteer.

On entering jail Byrne assumed leadership of the republican prisoners there. As in the 1970s and 80s the major issue at stake was that of political status. The prisoners mounted an escalating campaign in support of their demands, including rioting and the destruction of prison property. This was brutally put down by the RIC who held little restraint in kicking and beating the prisoners.

Following this Byrne decided that the only form of agitation that would garnish enough publicity to see the prisoner’s demands met was hunger strike. As his health deteriorated the prison authorities decided to move Byrne from Limerick Gaol to the Limerick Workhouse.

The IRA viewed the workhouse as a soft target and the Limerick unit decided to undertake measures to release Byrne. Taking advantage of the time granted to visitors on April 6th a party of IRA men were sent as supposed visitors of Byrne. One, Batty Stack, was armed.

In the process of the struggle to release Byrne one RIC man was killed and Byrne was fatally wounded by a bullet that was at the time assumed to have come from an RIC fired weapon. This has since been placed in doubt by Stack’s admission that it was possibly the weapon he fired that ultimately wounded Byrne.

It is however a fact that the RIC were under orders to shoot to kill in the case of escaping political prisoners and that this in turn had a great bearing the situation. Byrne died on the night of April 6th on the floor of a labourer’s cottage.

This incident was in effect the straw that broke the camel’s back for the workers of Limerick, and set the fuse to light the fire of accumulated discontent based on both class and national oppression.

On April 8th ten thousand people accompanied the movement of Byrne’s tricolour draped coffin from the cottage to Saint John’s cathedral, and two days later the postal workers laid a wreath at his funeral.

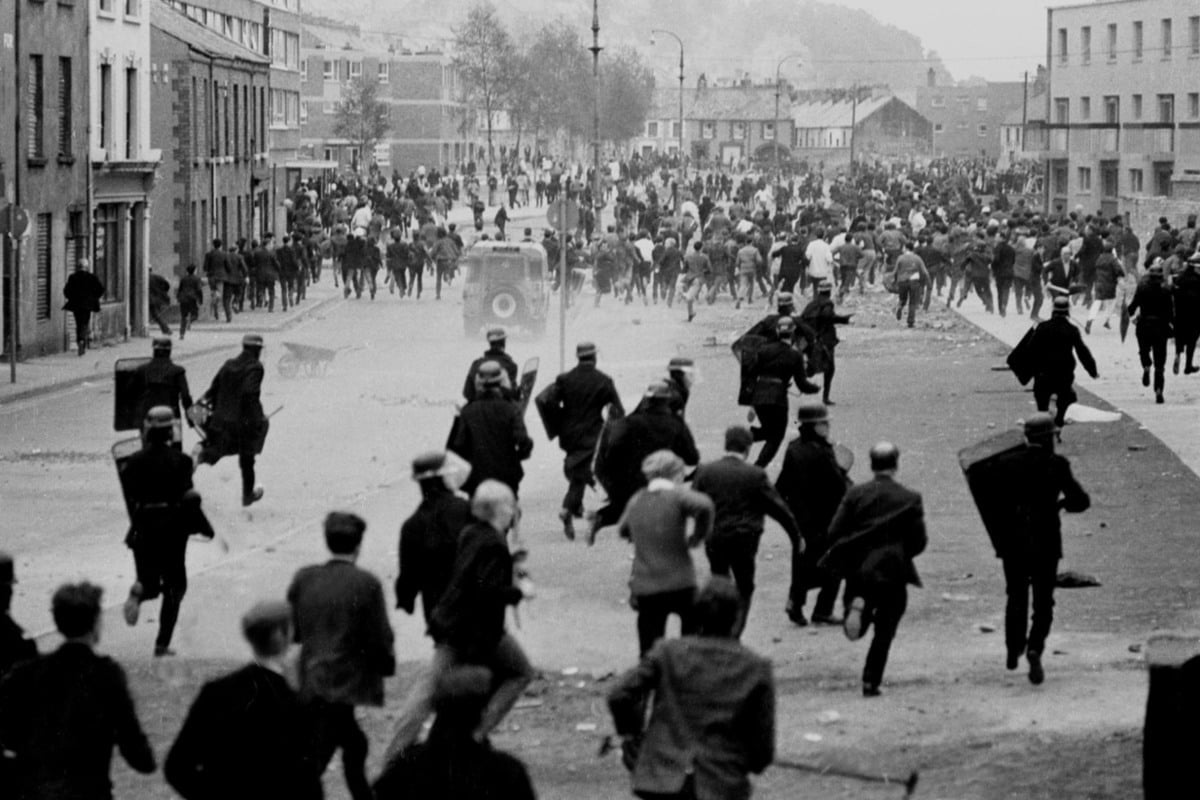

The British administration in Dublin Castle could not tolerate this and sought to punish the people of Limerick for their defiance. April 9th saw the Defence of the Realm Act (emergency legislation allowing unfettered military rule) used to declare part of Limerick a “Special Military Area” (SMA). As a result the military was brought in to Limerick to administer what amounted to a partition of the town.

Under this new regime the working-class Thomondgate area to the north of the Shannon was cut off from the rest of the town as were two of the town’s biggest factories, the Cleeve’s creamery and the Walkers’ distillery.

Under the SMA workers travelling from north to south or vice versa would have to apply for permits through the military and present them to soldiers four times a day, as they crossed two bridges on each trip there and back. Those who applied for a permit had to pass through a degrading process under which their names and details such as height and weight were taken. It was clear that permits were not going to be provided to those suspected of republican or socialist sympathies.

These measures were promptly enacted and took the local labour movement by surprise. However, the workers of Cleeve’s refused to apply for permits and arranged a strike from Monday 14th. The local trades council met the Sunday before this and decided to declare a general strike of all workers in Limerick.

A strike committee made up of the carpenter John Cronin, head of the trades council, trades council treasurer, the printer James Casey, and an engineering worker named James Carr. Subcommittees were also elected to run propaganda, finance, food and vigilance.

Cronin declared that “We, as organised workers, refuse to ask them for permits to earn our daily bread, and this strike is a protest against their action. What we want is to have this ban removed so that the workers may have free access to their work in and out of their native city. It is our intention to carry on the strike until this ban is removed. This strike is likely to become more serious.”

Posing the Question of Power

It was evident that this was not a normal strike but one that was pushing the question of power to the fore. The strike committee planned to keep basic utilities running, although the street lights were switched off. The only shops which were allowed to open were the bakers and grocers, between 2pm and 5pm.

The strike committee appointed patrols to ensure this was obeyed, with those who chose to breach the rules being punished with later opening hours the following day. Permits were issued by the strike committee to allow merchants to carry products including food and coal to and from the railway station.

The local capitalists were angry at having to tolerate the disturbance to their businesses that the SMA entailed but were far more concerned by the threat of the emergence of the embryo of a worker’s government.

This was particularly true after day four of the strike when the army offered the employers a concession in the form of the opportunity to distribute permits to their workers. The strikers resolutely rejected this, incensed that the bosses of all people should be given the right to determine who had access to their town.

The fundamental class contradiction between labour and capital expressed itself firstly through a dispute with the coal merchants. On the Thursday when the offer from the army was made, the merchants refused to open their shops after being instructed to do so by the strike committee, having done so the previous day. Faced with the RIC and the British army the strike committee was left with little option but to accept this decision.

This weakness exposed the short life that a situation of dual power can hold. In the case of Limerick it was clear that either the strike committee, dubbed a soviet by the press, could succeed through escalating the strike or succumb to the resistance of the employers and the state.

The strikers had no arms, and although most enterprises were following the orders of the soviet they did not actually control them. As long as big capital remained in private hands, incidents such as those with the coal merchants made it impossible for the soviet to plan the economy of even a small town like Limerick over a short period of time.

The Working Class can run Society

The experience of the soviet demonstrated not only the ability of the working class to run society for itself, without bosses, but also its ingenuity in the face of adversity.

Faced with a lack of currency the strike committee issued its own currency, with values of one five and ten shillings.

The propaganda committee also arranged the distribution of a “workers’ bulletin”, famously inscribed as having been “Issued by the Limerick Proletariat”. At first it served as a basic information sheet for the strikers but gradually evolved into a more general publication resembling a newspaper and included humour and propaganda.

The audacity and bravery of the strikers cannot be in doubt. Not content merely with the achievement of having partially taken Limerick in the face of the biggest military power in the world at the time they also attempted to extend the strike and challenge the workings of the SMA.

The Sunday after the strike started, which was also Easter Day, arguably marked the high point of the Limerick Soviet. Approximately a thousand inhabitants of Limerick went just out of the city boundaries, supposedly to go to watch a hurling or Gaelic football match (it is unclear which) but many survivors have since said in reality this was ruse.

On their way back home, attempting to re-enter the town through the SMA, the crowd were asked for permits which they did not hold. They then moved round circling the troops and making way for another citizen to ask to leave. The workers’ bravery went to the extent of defying armoured cars and they only dispersed hours later, as soldiers threatened to fire on them.

The next day, after being taken in by families in the Thomondgate area, the protestors were cheered as they headed for a side station a few miles away and boarded a train bound for Limerick, only to unlock the carriage doors and overwhelm a weak spot in the SMA’s defence that was guarded by a solitary military police officer.

Solidarity

The mood of solidarity with the soviet extended beyond Limerick itself, as the collection of food from local small farmers demonstrated.

However, perhaps more important is the support that the soviet received from the Irish labour movement, with trades councils in Cork, Wexford, Tralee and Ennis all pledging support.

The soviet also received a donation of the then considerable £1,000 from the Dublin ITGWU. Support was also extended from the Scottish Trade Union’s Congress, the Independent Labour Party, the British Socialist Party and Sylvia Pankhurst’s socialist newspaper ‘Worker’s Dreadnought’.

Yet it was the labour movement’s leadership itself which failed the workers of Limerick. The Irish TUC dispatched Thomas Johnson to Limerick on hearing about the unfolding strike. He indicated that ITUC was prepared to mobilise the Irish working class in support of Limerick, declaring, “Shall the military power of any nation or group of nations, be suffered to determine the fortunes of peoples over whom they have no right to rule, except the right of force ?’ Limerick’s reply is ‘No’, and all Ireland is at her back.”

As is typical of reformist leaders however these proved to be words of little substance. The betrayal by the trade union leadership will be no surprise to Irish workers; just as the ITUC leaders of 2009 pledge to organise a general strike ended in betrayal so did that of the leaders of 1919.

Under pressure from the British trade union leaders, Sinn Fein and the Catholic Church the ITUC leaders betrayed the working class and refused to mobilise for a general strike, instead proposing a complete evacuation of Limerick as an alternative protest. This was rejected by a dismayed strike committee as unworkable and ineffective.

The strike ultimately collapsed when the local Bishop, Doctor Hallinan and the Sinn Fein Mayor, Alphonsus O’Mara, who had been relatively supportive of the action up to this point, wrote a letter to the strike committee requesting the strike be brought to an end.

After more than a week on strike in isolation and faced with the full strength of the state mobilised against them the strike committee called an end to the action and those workers of Limerick who could go to work without a permit returned to work on April 25th. After May 5th, when the SMA was lifted, all the workers of Limerick returned to work.

Nationalist Betrayal

It is of no surprise to Marxists that the church or nationalist politicians betrayed the workers of Limerick. The failure of the Irish labour leaders in this instance is fundamentally rooted not in this or that detail but with their tail-ending of Sinn Fein.

Throughout the life of the Limerick Soviet, the petty bourgeois nationalist newspaper the ‘Irish Independent’ warned of action that would place the burden of working class activity on ‘nationalist Ireland’.

Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Fein, had warned his fellow party members in January 1919 that “The General Strike is a weapon that might injure as much as serve. It would be injudicious at present and might be injudicious at any time.”

The actions of the union leaders are bound up with the Labour Party’s decision to collaborate with Sinn Fein rather than standing independently in the 1918 elections and the support that the Labour and trade union leaders subsequently offered them led ultimately to the partition of Ireland in 1921.

This was not in the interests of the Irish working class and small farmers but the big bourgeoisie who remain to this day the gate keepers of British and international imperialism.

Only three years after his death the ITUC leaders had forgotten the teachings of Connolly who famously stated, “The cause of labour is the cause of Ireland, the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour. They cannot be dissevered.”

Once again Ireland is entering a period of intensified class struggle and once again the Irish union leaders have attempted to put a break on the working class by postponing indefinitely the one day general strike that was due to take place in March.

Sinn Fein, having spent the period since the Good Friday Agreement administering a right-wing program of cuts side by side with the unionist parties, attempted to demagogically co-opt the struggle of the Visteon workers in Belfast.

The lessons of Limerick are clear; only the independent militant action of the working class can deliver a socialist, united Ireland.

In recent months the Labour Party has seen its support double as the working class has taken to the streets, as in 1919 it is only by fighting on a socialist program and rejecting coalition with the parties of bourgeois and petty bourgeois nationalism can the working class emerge victorious in the struggles ahead.