With Jeremy Corbyn on course to win another landslide victory in the contest for the Labour leadership, the Party Establishment are preparing the ground for a split. Rob Sewell, editor of Socialist Appeal, looks back at the Labour split of 1931 to analyse the important lessons of Labour’s history for today’s tumultuous events.

With Jeremy Corbyn on course to win another landslide victory in the contest for the Labour leadership, the Party Establishment are preparing the ground for a split. Rob Sewell, editor of Socialist Appeal, looks back at the Labour split of 1931 to analyse the important lessons of Labour’s history for today’s tumultuous events.

“Political realignments do not happen often in British politics…But the space may be opening up for a new, pro-European, economically liberal and socially compassionate alternative to pinched nationalism and hard-left socialism.”

The Financial Times (30/6/16)“I would be lying if I said it would be easy to stay in a party led by Mr Corbyn where people like me are so unwelcome.”

Jess Phillips, Labour MP (The Financial Times, 7/8/16)“We are teetering on the edge of a precipice here. The Party could be split. The Party that has been here for 116 years as the greatest source of social and economic justice could be bust apart and disappear.” Owen Smith, Labour MP (The Guardian, 5/8/18)

Not surprisingly, discussions about splits and political realignments have become very popular in recent months. With the appointment of Theresa May as Tory leader, the deep-seated divisions within the Tory party have been papered over, at least for the time being. Now all eyes are centred on the divisions and civil war within the Labour Party.

The Corbyn revolution

The rise of Jeremy Corbyn came as an almighty shock to the British Establishment. It was never supposed to happen. So what went wrong?

The rise of Jeremy Corbyn came as an almighty shock to the British Establishment. It was never supposed to happen. So what went wrong?

Under the Blair years, the Party became infested with right-wing careerists and the Party’s working-class base was bureaucratically shunted aside. However, the crisis of capitalism has turned everything on its head – not only in Britain, but in the United States, across Europe, and internationally. Everything has been put into the melting pot as millions of people search for a way out of the crisis.

This was the background for the unexpected victory of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, which has unleashed an almighty battle within the Party. Today, the right wing, with the full support of the ruling class, is hell-bent on discrediting, then ousting Corbyn, and re-establishing their apparently God-given right to have control of the Party. This struggle is not a secondary struggle, but represents a fight to the finish.

The reason for the ferocity is that this is a fight for the future of the Labour Party. Up until now, the British ruling class has exercised control over the Party through its right-wing leaders. It seemed to be in permanently safe hands. Tony Blair was their arch representative. His aim on behalf of the Establishment was to destroy the Labour Party and create a Tory Party Mark II. Despite all their efforts, however, the New Labour architects of Blair, Mandelson, et al. never quite succeeded in breaking the Party’s links with the organised working class.

Today, the grip of the right wing has been shattered by hundreds of thousands of Corbyn supporters joining the Party. For decades, anger and frustration had been building up within society, and this pressure was seeking an outlet. Corbyn became a political reflection of – a lightning rod for – this anger.

The ruling class was aghast at his victory. “The scale of Jeremy Corbyn’s victory in the Labour party’s leadership election is a political earthquake”, stated a gob-smacked Martin Wolf in the Financial Times of last year. “Britain’s Labour Party is neither Greece’s Syriza nor Spain’s Podemos. It has been in power for just less than 40% of the time since 1945.” (20/9/15)

How could such a thing happen? It was utterly intolerable to the Labour Establishment and the ruling class! They could never accept this left “takeover” and swore to destroy Corbyn and his revolution. If this meant a split, then so be it. Lord Mandelson openly admitted the existence of two Labour Parties that were (and are) in conflict. Frank Field, the right-wing Labour MP for Birkenhead, advocated that the Party appoint two leaders: one in Parliament (the real leader), and the other outside, thereby removing Corbyn as leader. The leadership challenger, Owen Smith – another Kinnock – wanted Corbyn to resign as leader and become Party “President” instead!

Open split?

The support for deselection of MPs amongst Labour’s ranks has hastened talk of a split in the Party. It is so intense that the right wing dominated PLP are openly talking about making a unilateral declaration of independence and announcing themselves as “the party”. They are even contemplating legal action to keep “Labour” in the title. Such an act would constitute an open split, as was seen in 1931 and 1982.

Lord Owen, a member of the “Gang of Four” who split from Labour to form the SDP (Social Democratic Party) in the early 1980s, has even suggested a timeline for a new split: “For at least two years, fight like hell, I would say. I wouldn’t contemplate a new party until the end of 2017.” Lady Shirley Williams, another Gang of Four member, supported him saying, “eventually there will be a new party of the centre left”.

It is no shock to hear that leading Labour MPs have been in close discussions with leading Tories and Liberal Democrats about a possible political realignment. These careerists can see the writing on the wall. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together.

Events are moving extremely fast and processes are already coming to a head. Of course, plans to split the Labour Party are not new. The ruling class has encouraged splits whenever there has been a danger of the right losing control of the Labour Party, as in 1931 with the formation of the National Government and in 1981 with the formation of the SDP. Such splits were used to sabotage the Labour Party, preparing the way for a National or Tory government. Of course, there are many differences between now and then, but the direction of travel is the same.

The rot of careerism; the stink of Blairism

The main difference between then and now is that the Parliamentary Labour Party is even more rotten, corrupted and dominated by right-wing careerists.

The main difference between then and now is that the Parliamentary Labour Party is even more rotten, corrupted and dominated by right-wing careerists.

Under Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair, the tops of the Party became increasingly stocked with lawyers, solicitors and so-called professionals, wholeheartedly committed to the “wonders” of the market. “There is nothing wrong with capitalism with a social conscience or a human face”, said Lord Mandelson, a “Labour” man keen on becoming filthy rich. “I want a situation more like the Democrats and the Republicans in the US”, explained the war criminal, Tony Blair.

You could not put a cigarette paper between the bulk of Labour MPs and the Tories. This “growing together” went much further than even the “Butskellism” of the 1950s. The current breed of right-wing Labour MPs speak, dress and behave exactly the same as the Tories.

As one MP said, quoted in the Independent on Sunday back in 1995 after Blair became leader, “Tony [Blair] is surrounding himself with people who are clever, able, upper-middle-class and arrogant, and who do not respect the Labour Party.” Nothing whatsoever has changed for these people since then. In fact, they have only ever treated the Party as a vehicle for their careers.

The degeneration of the Parliamentary Labour Party has gone far. It means that whereas in the past a right-wing split was a relatively minor affair, as in 1931, a future split would see a large proportion of the PLP cross the floor. The fact that 172 of them voted for a motion of no confidence in Corbyn – the democratically elected leader – shows their true loyalty. More than 60 resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in a coup to force him out.

A big majority of such careerists are likely to split away as soon as they have their marching orders from big business. “The memory of Ramsay MacDonald’s betrayal of the 1931 government is etched in blood on the Party’s memory”, explained The Financial Times (23/4/16).

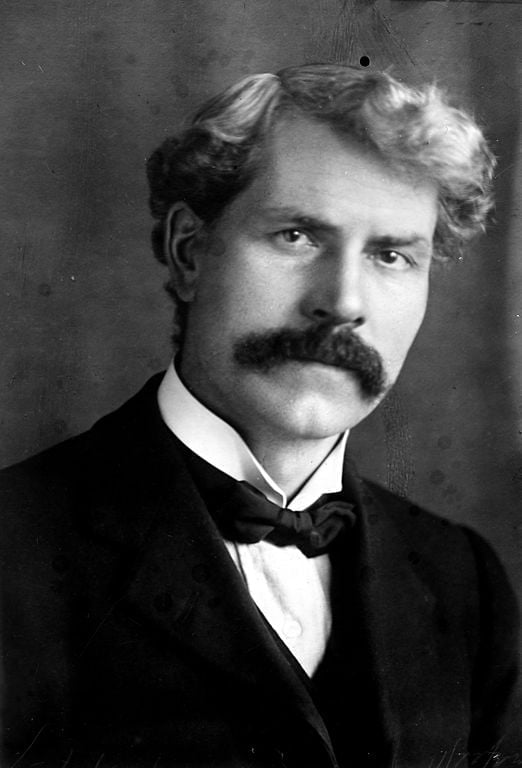

The split in 1931 constituted one of the greatest betrayals in Labour history, when Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister, stabbed the Party in the back and joined the Tories and Liberals to form a “National” Government. For him, “Country” came before Party. MacDonald stood for the “national interest” – the national interest being of course the interests of big business.

Then as now, there are those in the Party leadership who will jump ship when the time comes. It is better to deselect them now before they jump.

The same types carried out the great betrayal of 1931. Then, facing certain opposition to cuts and austerity in the Labour Cabinet, Prime Minister MacDonald, Chancellor Philip Snowden, Lord Privy Seal J.H. Thomas and Lord Sankey resigned and crossed the floor to join the National Government. Now, 66 Labour MPs have voted with the Tories over the bombing of Syria and 140 of them over Trident renewal.

Crisis and slump

Of course, the right-wing Labour politicians are always subject to flattery by the ruling class for their statesman-like behaviour.

“Mr Snowden, with rare though belated courage, has shown that he at least knows where that duty lies, and, whatever the attitude of the rest of his Party, the public will never grudge him any assistance which he may need in carrying through his difficult task,” declared the London Times in early 1931.

Then as now, capitalism was experiencing a deep world slump. In 1929, just over one million were unemployed, but this had risen to 2,700,000, 22% of the insured workers, in the summer of 1931. Production had declined 8% below that of 1913. The growing budget deficit threatened to force Britain off the gold standard. The government was informed that loans could be secured from the bankers, but only with massive cuts in public spending.

The Parliamentary sponsored May Committee recommended that “economies” amounting to £96 million should be made, the majority of which should be in the form of cuts to unemployment benefits and the imposition of a means test system.

Labour Ministers such as MacDonald, Snowden, Henderson, Thomas and Graham made a counter proposal of some £56 million in cuts, which the majority of the Cabinet actually accepted. A minority still opposed them, who MacDonald accused of taking “the easy path of irresponsibility”.

But it was from outside the Cabinet that the biggest opposition to the cuts was seen. The TUC registered its firm opposition to the cuts. “Nothing”, wrote MacDonald, “gives me greater regret than to disagree with old industrial friends, but I really personally find it absolutely impossible to overlook dreadful realities, as I am afraid you are doing.”

The opposition of the TUC also stiffened the opposition inside the Labour Cabinet. Such opposition forced MacDonald’s hand. He fully understood that this would lead to a breach.

By this time, MacDonald and the leaders of the Tory and Liberal parties were in constant touch with the Palace. “In a strictly constitutional capacity he [the King] has rendered a signal service to his people”, noted The Times. George V met with Baldwin, the Tory leader, and Sir Herbert Samuel, the Liberal leader, to discuss the “national interest”.

Sir Herbert cynically informed the King:

“In view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working classes, it would be to the general interest if they could be imposed by a Labour Government. The best solution would be if Mr Ramsay MacDonald, either with his present, or with a reconstituted Labour Cabinet, could propose the economies required. If he failed to secure the support of a sufficient number of his colleagues, then the best alternative would be a National Government composed of members of the three parties. It would be preferable that Mr MacDonald should remain Prime Minister in such a National Government.”

So the authority of MacDonald as former Labour Prime Minister would be used to enact the austerity. MacDonald graciously accepted this role. With the Labour Cabinet partially divided, the creation of a National Government was seen as the only viable option. After its formation, Snowden boasted to MacDonald that “tomorrow every Duchess in London will be wanting to kiss me.”

The ruling class were also extremely delighted with the outcome. A strong “national” government had been formed. “All concerned are to be warmly congratulated on this result,” commented The Times.

MacDonald’s former Labour colleagues were stunned by the speed of events. Arthur Henderson, secretary of the Party, claimed that they had all agreed with the need for sacrifices and a balanced budget but had been thereafter kept in the dark.

When the split came, some right-wingers like Henderson and J.R. Clynes did not follow MacDonald but remained behind in the Party to prevent it falling into the “wrong” hands, given that the betrayal would inevitably radicalise the movement.

“There is a third danger ahead”, wrote the Times, “but it is a danger to the nation rather than to the Government. Broadly speaking, the whole of the Socialist Party will be reconsolidated in Opposition – with this enormous difference, that they will have lost the guidance of leaders few indeed in numbers but the ripest of all in practical experience of affairs…The Labour Party…will now be definitely controlled by its more prejudiced and ignorant elements.” (26/8/31).

MacDonald then called a panic General Election towards the end of August 1931, resulting in a landslide victory for the National Government – which gained 554 seats and 70% of the vote. The Labour Party, given the split, lost heavily at the polls, gaining only 52 seats and 6.5 million votes.

Kick out the traitors

While the Labour leaders were regrettably saddened over this “great loss to the Labour Movement”, the angry rank and file – the “ignorant elements” – forced the National Executive to expel MacDonald and others from the Party as traitors.

“The revulsion from MacDonaldism caused the Party to lean rather too far towards a catastrophic view”, observed Clement Attlee, Deputy Leader of the PLP.

“The attitude of the rank and file of the Party seems to me to be extremely dangerous at the moment” wrote Stafford Cripps, who felt the ground moving under his feet. “There is a strong tendency to discard the realities of the situation”, he added.

In other words, the Party’s rank and file reacted to the betrayal with disgust and a rejection of gradualism. As a result, Labour’s Annual Conference, cleansed of MacDonald and the other riff-raff, shifted decisively to the left and proclaimed that “the main objective of the Labour Party is the establishment of socialism.”

“At Leicester”, wrote Hugh Dalton, a future Labour Chancellor, “the floor several times ran away with the platform.”

“On the whole,” wrote a disorientated Beatrice Webb, “I rejoice in the crisis as I think it will clear the issue and purify the Party.”

The Independent Labour Party (a key affiliate of the Labour Party) at its 1932 Easter Conference stated that “the class struggle which is the dynamic force in social change is nearing its decisive moment…there is no time now for slow processes of gradual change. The imperative need is for Socialism now.” However, within a few months, the ILP took the decision to disaffiliate from Labour.

The Labour Party continued, however, to shift further to the left. In 1932, Harold Laski, a reformist theoretician, asked whether “evolutionary socialism (had) deceived itself in believing that it can establish itself by peaceful means within the ambit of the capitalist system.”

Another leading figure, Stafford Cripps, in a pamphlet entitled Can Socialism Come by Constitutional Means? warned that “the ruling class will go to almost any length to defeat Parliamentary actions if the issue is the direct issue as to the continuance of their financial and political control.” He then went on to advocate emergency powers for a Labour Government to tackle the crisis.

Calls for socialism

The Labour Party Conference passed a resolution, without dissent that: “the common ownership of the means of production and distribution is the only means by which the producers by hand and brain will be able to secure the full fruits of their industry.”

Another resolution demanded that:

“Socialist legislation must be immediately promulgated, and that the Party shall stand or fall in the House of Commons on the principles in which it has faith.”

“Let us lay down in some such resolution as this the unshakeable mandate that they (the Labour Government) are to introduce at once, before attempting remedial measures of any other kind, great socialist measures, or some general measure empowering them to nationalise the key industries of the country.”

Arthur Henderson, the Party chairman, was almost howled down by the delegates when he opposed the resolution for tying the hands of the leadership. “He was so disgruntled at the general atmosphere of the Conference that he told me on the last morning that he had decided to resign the Leadership”, explained Hugh Dalton.

The right wing, although on the defensive, were determined to keep their hold on policy. A secret “City group” was established behind the backs of the Party, as a direct link to big business. “Early in 1932 I took some part in encouraging the formation of a small group of City people to advise the Party on questions of which they had practical knowledge”, explained Dalton. “The membership, and even the existence, of this group was kept for some time a very close secret…Its secret name is XYZ.”

This shows the clear role of the right wing within the Labour Party. It was through such individuals – overt and covert – that the ruling class exercised control.

Today, while a split away of the Blairite members of the PLP could initially hinder or even prevent a Corbyn-led Labour victory in a general election, it will propel the Party far to the left.

Failure of reformism

Following 1931, Attlee and Cripps put out a warning in a memorandum against the adoption of gradual half-measures:

“So long as Capitalism holds the power and the control, so long will it use every weapon to retain it…The result of failure of a Labour Government will be the immediate splitting of the Labour Party into fragments, to the great and permanent advantage of the perpetration of the capitalist regime. From these fragments will probably be built up amongst others a strong revolutionary party and the eventual issue will be fought out between that party and Capitalism.”

The betrayal and shipwreck of the Labour Government of 1929-31 was the result of its attempt, in the middle of a slump, to manage the capitalist system. It exposed the failure of reformism.

The key lesson from this debacle, especially in a period of deep crisis, is that it is not the task of the Labour Party to rescue capitalism but to do away with it.

That is why the Marxists are consistently campaigning for a bold socialist programme to put an end to this system of dole queues and hardship. Very shortly, such a message will find a colossal echo in the movement of the working class.

The Labour Party was founded to represent the working class in Parliament. Under the impact of the Russian Revolution, it adopted a socialist aim, which was abandoned and ignored by the right wing. Instead, they have used their positions – right up to the present – to further their careers and defend capitalism. It is time such “representatives” were booted out and replaced with genuine class fighters.

For the advanced sections of workers and the youth, the experience of 1931 contains vital lessons for the future. In the fight to support Corbyn, we must urgently cleanse the Party of careerists and Tory carpetbaggers and commit the Labour movement to immediately implement socialist policies to end this crisis-prone system. In this struggle, the Marxist tendency will play a leading role.