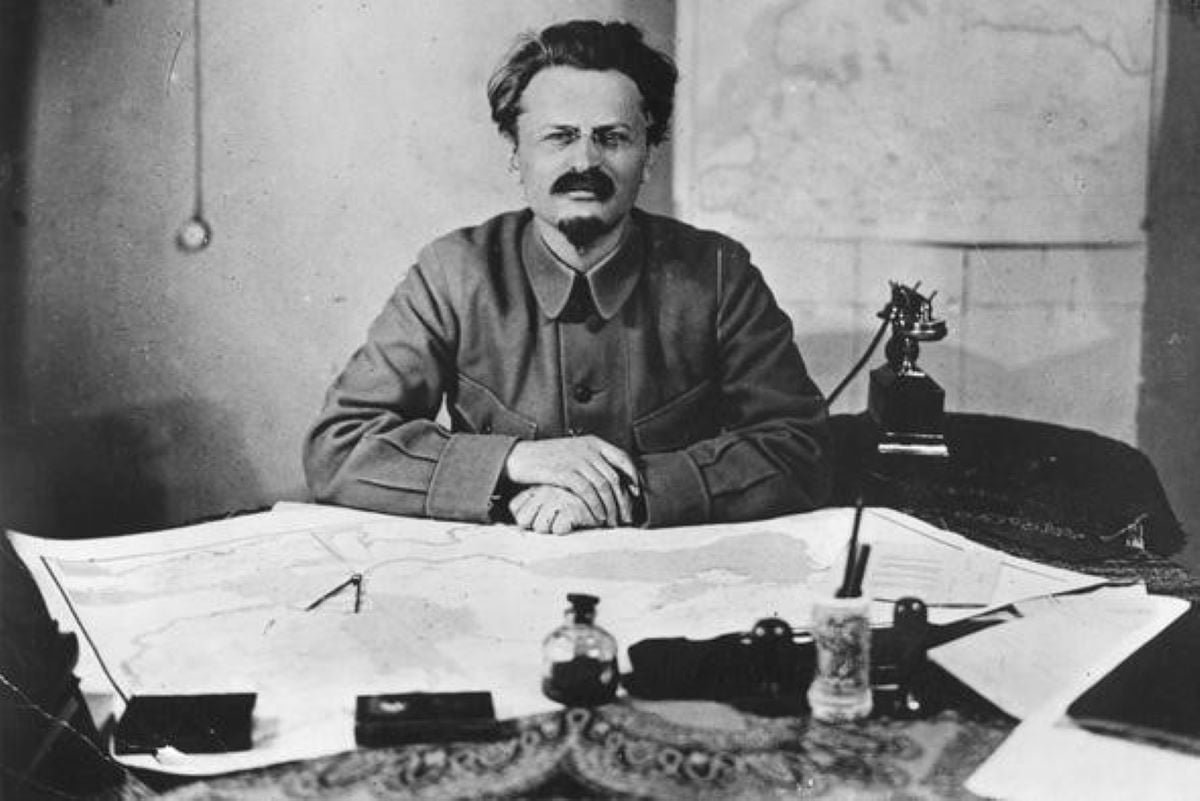

Leon Trotsky was best-known to the world at large as a man of action.

As the film of his life unreels in review, he can be seen struggling with the Russian workers against Czarism until he leaps to the chairmanship of the Petrograd Soviet in [the 1905 Russian Revolution]; tirelessly mobilising the masses, as orator and journalist, until he prepares them for the October insurrection; organising, commanding, and bringing to victory the Red Army; and finally fighting against internal and world reaction for the defence of the international socialist revolution.

Trotsky was all this – and much more. He was not simply an agitator, political leader, warrior, and statesman; he was no less brilliant as a pamphleteer, biographer, historian, man of thought and letters. Like Lenin, he mirrored and incarnated within himself the Marxist ideal of the unity of thought and action.

Bernard Shaw, no poor judge, once called him “The Prince of Pamphleteers.” He himself, when questioned as to the nature of his progression, styled himself, not without irony, a journalist. Had history permitted, he once confessed, he would have preferred to devote his entire life, and not simply the enforced intervals granted him in exile or in prison, to creative literature.

His talents, the world admitted, were equal to this aspiration. His gifts of expression, his force of logic, his psychological insight, and whiplash irony extorted admiration even from his foes. What a novelist was lost to literature, sighed many a devotee of belles-lettres, upon reading the portraits of the individuals who appear in his History of the Russian Revolution.

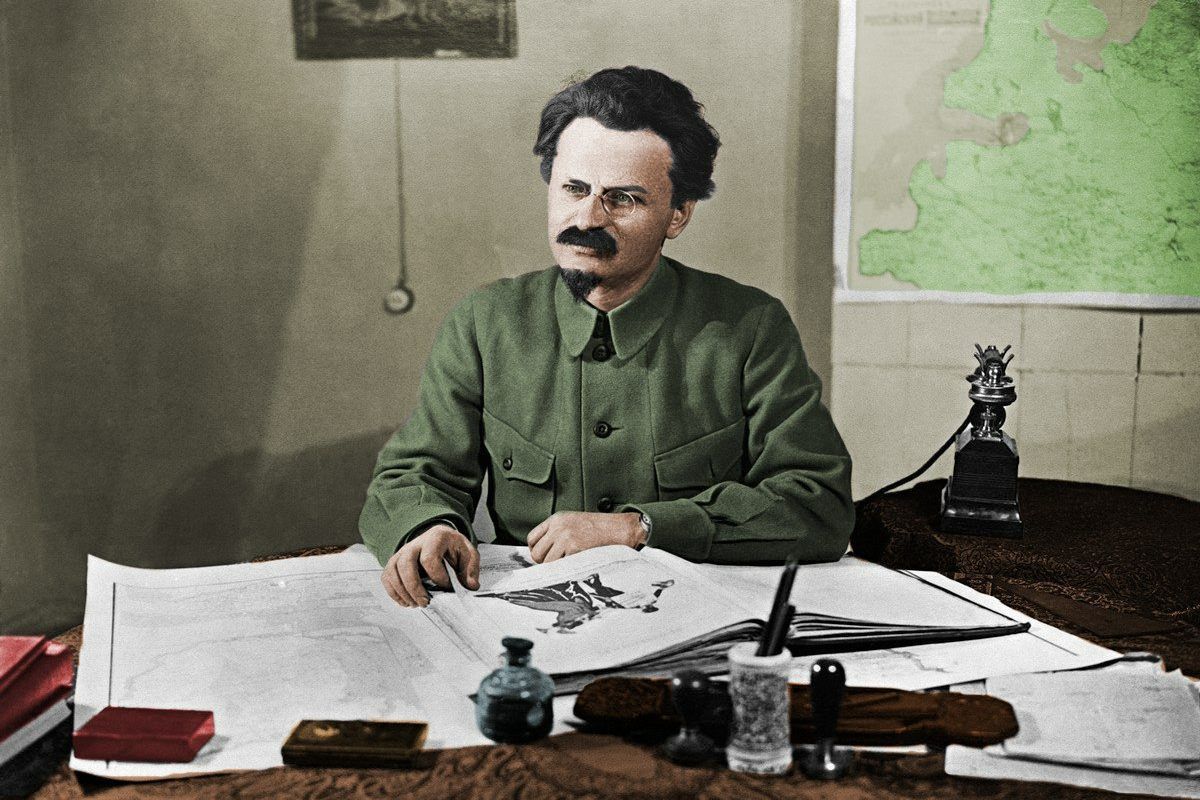

Whatever pure literature might have lost, the world of human culture gained by Trotsky’s marriage to Marxism. A man of broadest culture and of delicately discerning taste, his interests had a universal circumference. He wrote sheaves of articles and essays on many diverse topics in art, science, manners, morals, housing, sports, and military technique, among other matters.

In whatever directions his interests radiated, they were united in a single centre. He wrote always from the standpoint of the socialist revolution. This was the height upon which he stood and viewed the march of humanity through past, present, and future. Marxism was the scientific method animating and guiding all his expression in thought and action.

Scanning the many-volumed row of Trotsky’s collected works, we can single out his summary of the lessons of the 1905 Revolution, Results and Prospects; his exposition of The Permanent Revolution; such works as Communism and Terrorism explaining to the workers the significance of the October Revolution and defending it against its traducers; and his monumental History of the Russian Revolution. At his death he was engaged in completing biographies of Lenin and Stalin. [Note: in 2016, members of the Revolutionary Communist International completed and published Trotsky’s unfinished masterpiece Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and his Influence.]

Just as Trotsky drew upon the classical work of Marx and Engels, so the present and prospective generations of socialist revolutionaries will turn to his works for indispensable knowledge, guidance, and inspiration.

Originally published in Vol. 5 No. 34 of Socialist Appeal – the paper of the Socialist Workers’ Party; the US section of the Fourth International – under the title ‘The Written Heritage’.

Delve more into the life and ideas of Leon Trotsky

Articles

- In memory of Leon Trotsky – Alan Woods

- Trotsky’s final struggle against Stalinism – In defence of genuine Marxism – Rob Sewell

- 100 years since the founding of the Left Opposition: In defence of Trotskyism – Rob Sewell

Books

- My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography – Leon Trotsky

- Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood For – Ted Grant and Alan Woods

- Catalogue of Trotsky’s writings from Wellred Books Britain

Videos

- Documentary: Leon Trotsky – The life of a revolutionary

- Trotsky and the Permanent Revolution – Jorge Martín