Today, 4 January 2023, marks the centenary of Lenin’s dictation of his postscript to his ‘Letter to the Congress’, also known as his ‘Testament’. In it, Lenin took up the struggle against the bureaucratisation of the Soviet state, which was threatening to derail all the gains of the revolution.

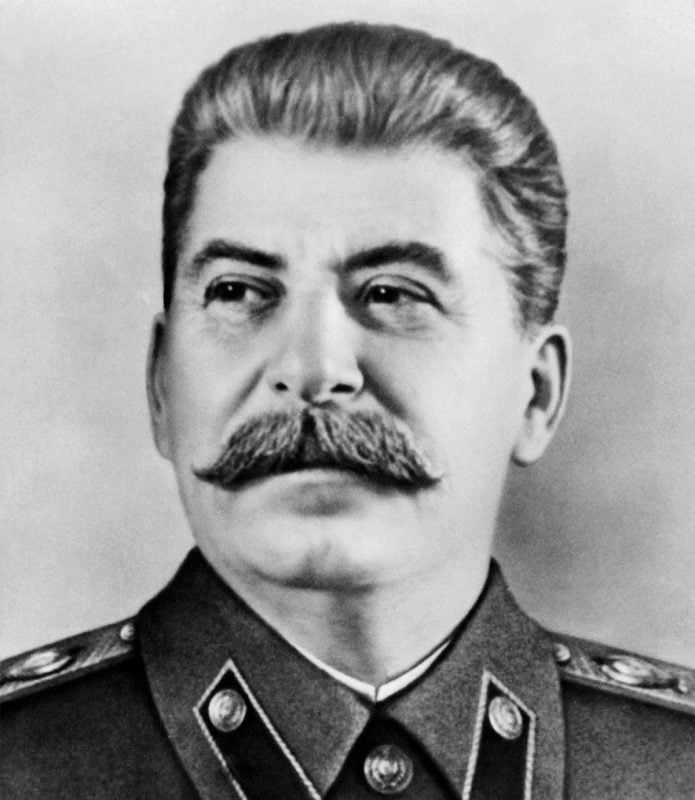

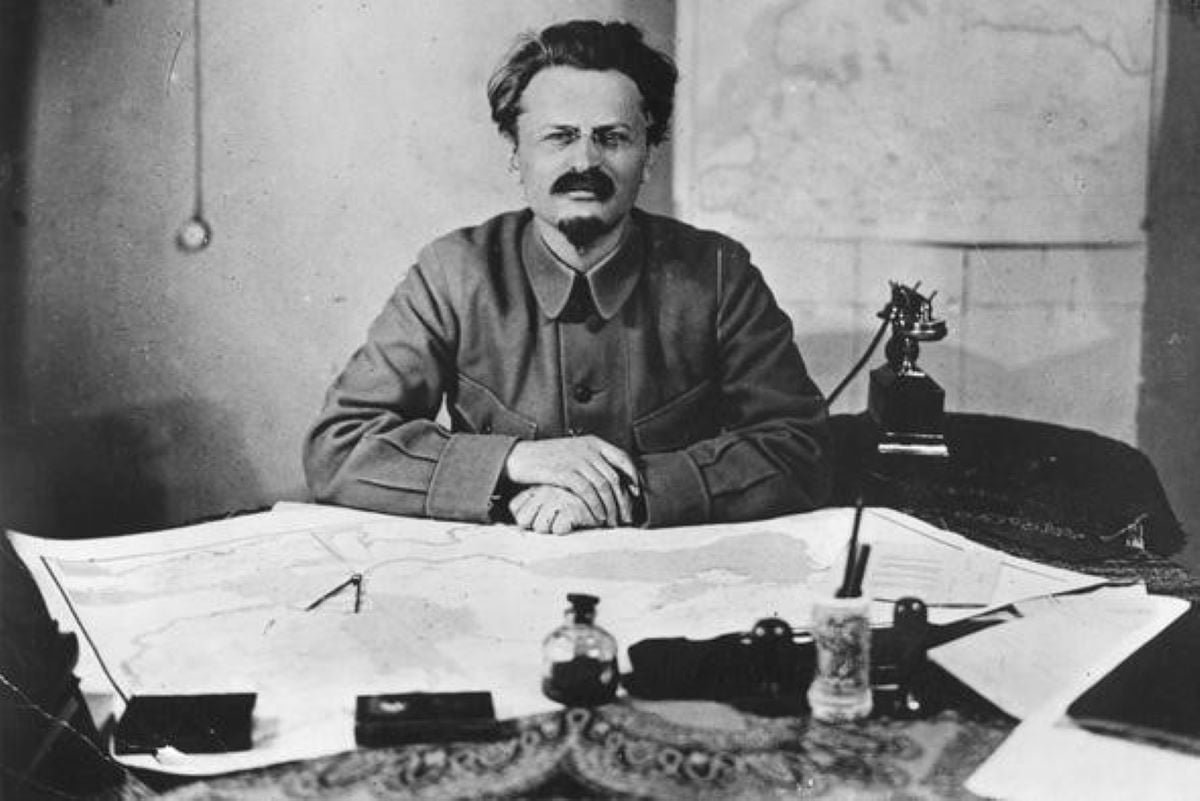

Lenin’s Testament, in conjunction with his last articles and letters, give evidence to the importance that he attached to the danger of the growing bureaucracy. In his letter and postscript, Lenin explicitly calls for the removal of Stalin as general secretary of the Communist Party, and contrasts him to Trotsky, who he described as “the most capable man on the present CC”.

Yet Lenin’s letter was not read out to the congress of the Communist Party, and was suppressed by the Stalinists for decades.

We are therefore taking this opportunity to republish an extract from the book Lenin and Trotsky: What they really stood for, by Alan Woods and Ted Grant, that deals in detail with Lenin’s Testament, and his struggle against Stalin and the bureaucracy.

Lenin and Trotsky: What they really stood for is available to purchase in print and ebook editions from wellredbooks.co.uk

Lenin’s struggle against bureaucracy

By Alan Woods and Ted Grant

[The Marxist method] explains bureaucracy as a social phenomenon, which arises for definite reasons. Lenin, approaching the question as a Marxist, explained the rise of bureaucracy as a parasitic, capitalist growth on the organism of the workers’ state, which arose out of the isolation of the revolution in a backward, illiterate peasant country.

In one of his last articles, ‘Better Fewer, But Better’, Lenin wrote:

“Our state apparatus is so deplorable, not to say wretched, that we must first think very carefully how to combat its defects, bearing in mind that these defects are rooted in the past, which, although it has been overthrown, has not yet been overcome, not yet reached the stage of a culture that has receded into the past.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 487)

The October revolution had overthrown the old order, ruthlessly suppressed and purged the Tsarist state; but in conditions of chronic economic and cultural backwardness, the elements of the old order were everywhere creeping back into positions of privilege and power in the measure that the revolutionary wave ebbed back with the defeats of the international revolution.

Engels explained that in every society where art, science and government are the exclusive of a privileged minority, then that minority will always use and abuse its positions in its own interests. And this state of affairs is inevitable, so long as the vast majority of the people are forced to toil for long hours in industry and agriculture for the bare necessities of life.

After the revolution, with the ruined condition of industry, the working day was not reduced, but lengthened. Workers toiled ten, twelve hours and more a day on subsistence rations; many worked weekends without pay voluntarily.

But, as Trotsky explained, the masses can only sacrifice their “today” for their “tomorrow” up to a very definite limit. Inevitably, the strain of war, of revolution, of four years of bloody Civil War, of a famine in which five million perished, all served to undermine the working class in terms of both numbers and morale.

The NEP stabilised the economy, but created new dangers by encouraging the growth of small capitalism, especially in the countryside where the rich ‘kulaks’ gained ground at the expense of the poor peasants.

Industry revived, but, being tied to the demand of the peasantry, especially the rich peasants, the revival was confined almost entirely to light industry (consumer goods). Heavy industry, the key to socialist construction, stagnated. By 1922, there were two million unemployed in the towns.

At the Ninth Congress of Soviets in December 1921, Lenin remarked:

“Excuse me, but what do you describe as the proletariat? That class of labourers which is employed by large-scale industry. But where is this large-scale industry? What sort of proletariat is this? Where is your industry? Why is it idle?” (Works, vol. 33, p. 174)

In a speech at the Eleventh Party Congress in March, 1922, Lenin pointed out that the class nature of many who worked in the factories at this time was non-proletarian; that many were dodgers from military service, peasants and declassed elements:

“During the war people who were by no means proletarians went into the factories; they went into the factories to dodge war. And are the social and economic conditions in our country today such as to induce real proletarians to go into the factories? No. It would be true according to Marx; but Marx did not write about Russia; he wrote about capitalism as a whole, beginning with the fifteenth century. It held true over a period of six hundred years, but it is not true for present-day Russia. Very often those who go into the factories are not proletarians; they are casual elements of every description.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 299)

The disintegration of the working class, the loss of many of the most advanced elements in the Civil War, the influx of backward elements from the countryside, and the demoralisation and exhaustion of the masses was one side of the picture.

On the other side, the forces of reaction, those petty bourgeois and bourgeois elements who had been temporarily demoralised and driven underground by the success of the revolution in Russia and internationally, everywhere began to recover their nerve, thrust themselves to the fore, taking advantage of the situation to insinuate themselves into every nook and cranny of the ruling bodies of industry, of the state and even of the Party.

Immediately after the seizure of power, the only political party which was suppressed by the Bolsheviks was the fascist Black Hundreds. Even the bourgeois Cadet Party was not immediately illegalised. The government itself was a coalition of Bolsheviks and Left Social Revolutionaries.

But, under the pressure of the Civil War, a sharp polarisation of class forces took place in which the Mensheviks, SRs and ‘Left SRs’ came out on the side of the counter-revolution. Contrary to their own intention, the Bolsheviks were forced to introduce a monopoly of political power. This monopoly, which was regarded as an extraordinary and temporary state of affairs, created enormous dangers in the situation where the proletarian vanguard was coming under increasing pressure from alien classes.

In February 1917, the Bolshevik Party had no more than 23,000 members in the whole of Russia. At the height of the Civil War, when party membership involved personal risk, the ranks were thrown open to the workers, who pushed the membership to 200,000. But as the war grew to a close, the party membership actually trebled, reflecting an influx of careerists and elements from hostile classes and parties.

Lenin at this time repeatedly emphasised the danger of the Party succumbing to the pressures and moods of the petty-bourgeois masses; that the main enemy of the revolution was:

“everyday economics in a small-peasant country with a ruined large industry. He is the petty-bourgeois element which surrounds us like the air, and penetrates deep into the ranks of the proletariat. And the proletariat is de-classed, i.e. dislodged from its class groove. The factories and mills are idle – the proletariat is weak, scattered, enfeebled. On the other hand the petty-bourgeois element within the country is backed by the whole international bourgeoisie, which retains its power throughout the world.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 23)

The “purge” initiated by Lenin in 1921 had nothing in common with the monstrous frame-up trials of Stalin; there was no police, no trials, no prison-camps; merely the ruthless weeding out of petty-bourgeois and Menshevik elements from the ranks of the Party, in order to preserve the ideas and traditions of October from the poisonous effects of petty-bourgeois reaction. By early 1922, some 200,000 members (one-third of the membership) had been expelled.

Lenin’s correspondence and writings of this period, when illness was increasingly preventing him from intervening in the struggle, clearly indicate his alarm at the encroachment of the Soviet bureaucracy, the insolent parvenus in every corner of the state apparatus. Thus, in a letter to Sheinman in February, 1922:

“At present the State Bank is a bureaucratic power game. There is the truth for you, if you want to hear not the sweet communist-official lies (with which everyone feeds you as a high mandarin), but the truth. And if you do not want to look at this truth with open eyes, through all the communist lying, you are a man who has perished in the prime of life in a swamp of official lying. Now that is an unpleasant truth, but it is the truth.” (Works, vol. 36, p. 567)

Contrast this fearless honesty of Lenin with all the saccharine falsehoods with which all the Communist Party leaders and “theoreticians” fed the international communist movement about the Soviet Union for generations, and judge for yourself the depths of degradation in which the self-styled “Friends of the Soviet Union” have plunged the ideas and traditions of Lenin! Again, in a letter dated April 12, 1922:

“The more such work is done, the deeper we go into living practice, distracting the attention of both ourselves and our readers from the stinking bureaucratic and stinking intellectual Moscow (and, in general, Soviet bourgeois) atmospheres, the greater will be our success in improving both our press and all our constructive work.” (Works, vol. 36, p. 579)

At the Eleventh Congress, Lenin placed before the Party a searing indictment of bureaucratisation of the state apparatus:

“If we take Moscow,” he said, “with its 4,700 Communists in responsible positions, and if we take the huge bureaucratic machine, that gigantic heap, we must ask: who is directing whom? I doubt very much whether it can be truthfully said that the Communists are directing that heap. To tell the truth, they are not directing, they are being directed.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 288, our emphasis)

To carry out the work of weeding bureaucrats and careerists out of the state and party apparatus, Lenin initiated the setting up of RABKRIN (the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate) with Stalin in charge.

Lenin saw the need for a strong organiser to see that this work was carried out thoroughly; Stalin’s record as a party organiser appeared to qualify him for the post. Within a few years, Stalin occupied a number of organisational posts in the Party: head of RABKRIN, member of the Central Committee and Politburo, Orgburo and Secretariat. But his narrow, organisational outlook and personal ambition led Stalin to occupy the post, in a short space of time, as the chief spokesman of bureaucracy in the party leadership, not as its opponent.

As early as 1920, Trotsky criticised the working of RABKRIN, which from a tool in the struggle against bureaucracy was becoming itself a hotbed of bureaucracy. Initially, Lenin defended RABKRIN against Trotsky. His illness prevented him from realising what was going on behind his back in the state and party.

Stalin used his position, which enabled him to select personnel to leading posts in the state and party to quietly gather round himself a bloc of allies and yes-men, political nonentities who were grateful to him for their advancement. In his hands, RABKRIN became an instrument for building up his own position and eliminating his political rivals.

Lenin only became aware of the terrible situation when he discovered the truth about Stalin’s handling of relations with Georgia. Without the knowledge of Lenin or the Politburo, Stalin, together with his henchmen Dzerzhinsky and Ordzhonikidze, had carried out a coup d’état in Georgia.

The finest cadres of Georgian Bolshevism were purged, and the party leaders denied access to Lenin, who was fed a string of lies by Stalin. When he finally found out what was happening, Lenin was furious. From his sick-bed late in 1922, he dictated a series of notes to his stenographer on “the notorious questions of autonomisation, which, it appears, is officially called the question of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics”.

Lenin’s notes are a crushing indictment of the bureaucratic and chauvinist arrogance of Stalin and his clique. But Lenin does not treat this incident as an accidental phenomenon – a “regrettable mistake”, like the invasion of Czechoslovakia, or a “tragedy”, like the crushing of the Hungarian worker’s commune, but the expression of the rotten, reactionary nationalism of the Soviet bureaucracy. It is worth quoting Lenin’s words on the state apparatus at length.

“It is said that a united state apparatus was needed. Where did that assurance come from? Did it not come from the same Russian apparatus, which, as I pointed out in one of the preceding sections of my diary, we took over from Tsarism and slightly anointed with Soviet oil?

“There is no doubt that that measure should have been delayed until we could say, that we vouched for our apparatus as our own. But now, we must, in all conscience, admit the contrary; the state apparatus we call ours is, in fact, still quite alien to us; it is a bourgeois and Tsarist hotchpotch and there has been no possibility of getting rid of it in the past five years without the help of other countries and because we have been “busy” most of the time with military engagements and the fight against famine.

“It is quite natural that in such circumstances the ‘freedom to secede from the union’ by which we justify ourselves will be a mere scrap of paper, unable to defend the non-Russians from the onslaught of that really Russian man, the Great-Russian chauvinist, in substance a rascal and a tyrant, such as the typical Russian bureaucrat is. There is no doubt that the infinitesimal percentage of Soviet and sovietised workers will drown in that tide of chauvinistic Great-Russian riff-raff like a fly in milk.” (Works, vol. 36, p. 605, our emphasis)

After the Georgian affair, Lenin threw the whole weight of his authority behind the struggle to remove Stalin from the post of General Secretary of the party which he occupied in 1922, after the death of Sverdlov.

However, Lenin’s main fear now more than ever was that an open split in the leadership, under prevailing conditions, might lead to the break-up of the party along class lines. He therefore attempted to keep the struggle confined to the leadership, and the notes and other material were not made public.

Lenin wrote secretly to the Georgian Bolshevik-Leninists (sending copies to Trotsky and Kamenev) taking up their cause against Stalin “with all my heart”. As he was unable to pursue the affair in person, he wrote to Trotsky requesting him to undertake the defence of the Georgians in the Central Committee.

Needless to say, the documentary evidence of Lenin’s last fight against Stalin and the bureaucracy has been suppressed for decades. Lenin’s last writings were hidden from the Communist Party rank-and-file in Russia and internationally.

Lenin’s last letter to the Party Congress, despite the protests of his widow, was not read out at the Congress and remained under lock and key until 1956 when Khruschev and Co. published it, along with a few other items (including the letters on Georgia) as part of their campaign to throw the blame for all that had happened in the past thirty years on to Stalin’s shoulders.

[…]

Lenin warns of the danger of a split in the Party, because “our party rests upon two classes, and for that reason its instability is possible…” Lenin did not see the disagreement between Trotsky and Stalin as accidental, or flowing from “personalities” (although he gives a series of penetrating sketches of the personal characteristics of the leading members of the Party).

Lenin’s last letter must be seen in the context of his other writings of the previous few months, his attacks on bureaucracy and the bloc which he formed with Trotsky against Stalin.

Lenin worded his letter very cautiously (he had originally intended to be present at the Congress for which according to his stenographer Fotieva, he had “prepared a bombshell for Stalin”).

For each of the leading members, he gives both the positive and negative features of their character: in Trotsky’s case, he refers to his “exceptional abilities” (“the most able man on the Central Committee at the present time”) but criticises him for his “far-reaching self-confidence” and “a tendency to be too much attracted by the purely administrative side of affairs” – faults which, however serious they may be in themselves, have nothing whatsoever to do with the Permanent Revolution, “Socialism in one Country”, or any of the other canards invented by the Stalinists.

In relation to Stalin, Lenin writes that “Comrade Stalin having become General Secretary, has concentrated enormous power in his hands, and I am not sure that he always knows how to use that power with sufficient caution.”

That is already a political question, and linked up with Lenin’s struggle against the bureaucracy in the Party. In ‘Better Fewer, But Better’, written shortly before, Lenin commented: “Let it be said in parentheses that we have bureaucrats in our Party offices as well as in Soviet offices.” In the same work, he launched a sharp attack on RABKRIN, which was clearly meant for Stalin:

“Let us say frankly that the People’s Commissariat of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection does not at present enjoy the slightest authority. Everybody knows that no other institutions are worse organised than those of our Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection and that under present conditions nothing can be expected from this Peoples’ Commissariat.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 490)

In a postscript to his letter [written on 4 January 1923], Lenin advocated the removal of Stalin from the post of General Secretary, ostensibly on grounds of “rudeness” – but advocating his replacement with a man “who in all respects differs from Stalin only in superiority – namely, more loyal, more polite and more attentive to comrades, less capricious, etc.” The diplomatic mode of expression does not conceal the indirect accusation, very clear in the light of the Georgian events, of Stalin’s rudeness, capriciousness and disloyalty.

In presenting Lenin’s Testament as a document merely concerned with the “personalities” of the leaders, the Communist Party “theoreticians” fall into a completely vulgar misrepresentation of Lenin. Even if the Testament leaves room for ambiguity (it does not, except for slovenly minds) the whole body of Lenin’s last writings provide a clear programmatic statement of his position, which cannot be distorted.

Repeatedly, Lenin characterised the bureaucracy as a parasitic, bourgeois growth on the workers’ state, and an expression of the petty-bourgeois outlook – which penetrated the State and even the Party.

The petty-bourgeois reaction against October was all the more difficult to combat because of the exhausted state of the proletariat, sections of which were also becoming demoralised. Nonetheless, Lenin and Trotsky saw the working class as the only basis for a struggle against bureaucracy, and the maintenance of a healthy workers’ democracy as the only check on it. Thus, in one article Purging the Party Lenin wrote:

“Naturally, we shall not submit to everything the masses say because the masses, too, sometimes – particularly in time of exceptional weariness and exhaustion resulting from excessive hardship and suffering – yield to sentiments that are in no way advanced. But in appraising persons, in the negative attitude to those who have “attached” themselves to us for selfish motives, to those who have become “puffed-up commissars” and “bureaucrats”, the suggestions of the non-Party proletarian masses and, in many cases, of the non-Party peasant masses, are extremely valuable.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 39)

The rise of bureaucracy was understood by Lenin as the product of economic and cultural backwardness which was the result of the isolation of the revolution. The means of combating this were linked, on the one hand, with the struggle for economic progress and the gradual elimination of illiteracy, which was linked inseparably with the struggle to involve the working masses in the running of industry and the state.

Lenin and Trotsky always relied upon the masses in the fight against the “puffed-up commissars”. Only by the conscious self-activity of the working people themselves could the transition to socialism be assured.

On the other hand, Lenin repeatedly explained that the terrible strains imposed upon the working class by the isolation of the revolution in a backward country put immense difficulties in the way of the creation of a really cultured, and harmonious, classless society. Time and again Lenin stressed the problems that arose from the isolation of the revolution.

[…]

Lenin resolutely explained that the difficulties of the revolution: the problems of backwardness, of illiteracy, of bureaucracy could only finally be overcome by the victory of the socialist revolution in one or several advanced countries. This perspective, which was hammered home by Lenin hundreds of times from 1904-5 onwards, was accepted as a truism by the entire Bolshevik Party up to 1924. In the last months of his life, Lenin never lost sight of this fact. Among his last writings are a series of notes which made his position abundantly clear:

“We have created a Soviet type of state,” he wrote, “and by that we have ushered in a new era in world history, the era of the political rule of the proletariat, which is to supersede the era of bourgeois rule. Nobody can deprive us of this, either, although the Soviet type of state will have the finishing touches put to it only with the aid of the practical experience of the working class of several countries.

“But we have not finished building even the foundations of socialist economy and the hostile power of moribund capitalism can still deprive us of that. We must clearly appreciate this and frankly admit it; for there is nothing more dangerous than illusions (and vertigo, particularly at high altitudes). And there is absolutely nothing terrible, nothing that should give legitimate grounds for the slightest despondency, in admitting this bitter truth; we have always urged and reiterated the elementary truth of Marxism – that the joint efforts of the workers of several advanced countries are needed for the victory of socialism.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 206, our emphasis)

In these lines of Lenin there is not an ounce of “pessimism” or of “underestimation” of the creative capacities of the Soviet working class. In all the writings of Lenin, and especially of this period, there is at once a burning faith in the ability of the working people to change society and a fearless honesty in dealing with difficulties.

The difference in the attitudes of Stalinism and Leninism towards the working class lies precisely in this: that the former seeks to deceive the masses with “official” lies and smug illusions about the building of “Socialism in One Country” in order to lull them into passive acceptance of the leadership of the bureaucracy, while the latter strives to develop the consciousness of the working class, never patronising it with lies and fairy-stories, but always revealing unpalatable truths, in the full confidence that the working class will understand and accept the need for the greatest sacrifices, provided the reasons for them are explained honestly and truthfully.

The arguments of Lenin were designed, not to stupefy the Soviet workers with “socialist opium”, but to steel them for the struggles ahead – for the struggle against backwardness and bureaucracy in Russia and for the struggle against capitalism and for the socialist revolution on a world scale.

It was the sympathy of the working people of the world, Lenin explained, that prevented the imperialists from strangling the Russian Revolution in 1917-20. But the only real safeguard for the future of the Soviet Republic was the extension of the Revolution to the capitalist countries of the West.

At the Eleventh Congress of the Russian Communist Party – the last which Lenin attended – he emphasised repeatedly the dangers to the State and Party arising out of the pressures of backwardness and bureaucracy. Commenting on the direction of the State, Lenin warned:

“Well, we have lived through a year, the state is in our hands, but has it operated the New Economic Policy in the way we wanted in the past year? No. But we refuse to admit that it did not operate in the way we wanted. How did it operate? The machine refused to obey the hand that guided it. It was like a car that was going not in the direction the driver desired but in the direction someone else desired; as if it were being driven by some mysterious, lawless hand, God knows whose, perhaps of a profiteer, or of a private capitalist, or of both. Be that as it may, the car is not going quite in the direction the man at the wheel imagines, and often it goes in an altogether different direction.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 179, our emphasis)

At the same Congress Lenin explained, in a very clear and unambiguous language, the possibility of the degeneration of the revolution as a result of the pressure of alien classes.

Already the most farsighted sections of the émigré bourgeoisie, the Smena Vekh group of Ustryalov, were openly placing their hopes upon the bureaucratic-bourgeois tendencies manifesting themselves in Soviet society, as a step in the direction of capitalist restoration. The same group was later to applaud and encourage the Stalinists in their struggle against “Trotskyism”.

The Smena Vekh group, which Lenin gave credit for its class insight, correctly understood the struggle of Stalin against Trotsky, not in terms of “personalities” but as a class question, as a step away from the revolutionary traditions of October.

“The machine no longer obeyed the driver” – the State was no longer under the control of the Communists, of the workers, but was increasingly raising itself above society. Referring to the views of Smena Vekh, Lenin said:

“We must say frankly that the things Ustryalov speaks about are possible, history knows all sorts of metamorphoses. Relying on firmness of convictions, loyalty, and other splendid moral qualities is anything but a serious attitude in politics. A few people may be endowed with splendid moral qualities, but historical issues are decided by vast masses, which, if the few do not suit them, may at times treat them none too politely.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 287)

In these words of Lenin we find the defeat of the Left Opposition explained in advance with a million times more clarity than in all the pretentious theorising of the “intellectuals” about the relative psychological, moral and personal attributes of Trotsky and Stalin. The State power was slipping out of the hands of the Communists, not because of their personal failings or psychological peculiarities, but because of the enormous pressures of backwardness, of bureaucracy, of alien class forces, which weighed down upon the tiny handful of advanced, socialist workers and crushed them.

Lenin likened the relationship of the Soviet workers and their advanced guard to the bureaucracy and the petty-bourgeois and capitalist elements to that of a conquering and conquered nation.

History has shown repeatedly that for one nation to defeat another by force of arms is not of itself, a sufficient guarantee of victory. In the event of the cultural level of the victors being lower than that of the vanquished, the latter will impose its culture upon the conquerors. Given the low level of culture of the weak Soviet working class, surrounded by a sea of small property owners, the pressures were enormous. They reflected themselves not only in the State, but inevitably in the Party itself, which became the centre of the struggle of conflicting class interests.

Only in the light of all this can we understand Lenin’s position in the struggle against bureaucracy, his attitude to Stalin, and the contents of his Suppressed Testament. That document expresses his conviction that the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin is “not a detail, or is a detail which can acquire a decisive significance”, in the light of the fact that “Our party is based upon two classes.”

In a letter written shortly before the Eleventh Party Congress, Lenin explained the significance of conflicts and splits in the leadership in these words:

“If we do not close our eyes to reality we must admit that at the present time the proletarian policy of the Party is not determined by the character of its membership, but by the enormous undivided prestige enjoyed by the small group which might be called the Old Guard of the Party. A slight conflict within this group will be enough, if not to destroy this prestige, at all events to weaken the group to such a degree as to rob it of its power to determine policy.” (Works, vol. 33, p. 257)

What determined Lenin’s bitter struggle against Stalin was not his personal foibles (“rudeness”) but the role he played in introducing the methods and ideology of alien social classes and strata into the very Party leadership which should have been a bulwark against those things.

In the last months of his life, weakened by illness, Lenin turned more and more frequently to Trotsky, for support in his struggle against the bureaucracy and its creature, Stalin. On the question of the monopoly of foreign trade, on the question of Georgia, and finally, in the struggle to oust Stalin from the leadership, Lenin formed a bloc with Trotsky, the only man in the leadership he could trust.

Throughout this entire last period of his life, in numerous articles, speeches, and above all letters, Lenin repeatedly expressed his solidarity with Trotsky. On all the important issues we have mentioned, it was Trotsky whom he singled out to defend his point of view in the leading bodies of the party.

Lenin’s appraisal of Trotsky in the Suppressed Testament can only be understood in the light of these facts. Needless to say, all the evidence for the existence of this bloc between Lenin and Trotsky against the Stalin clique was kept under lock and key, for many years. But truth will out. The letters to Trotsky published in Volume 54, of the latest Russian edition of Lenin’s Collected Works, although even now not complete, are irrefutable proof of the bloc that existed between Lenin and Trotsky.