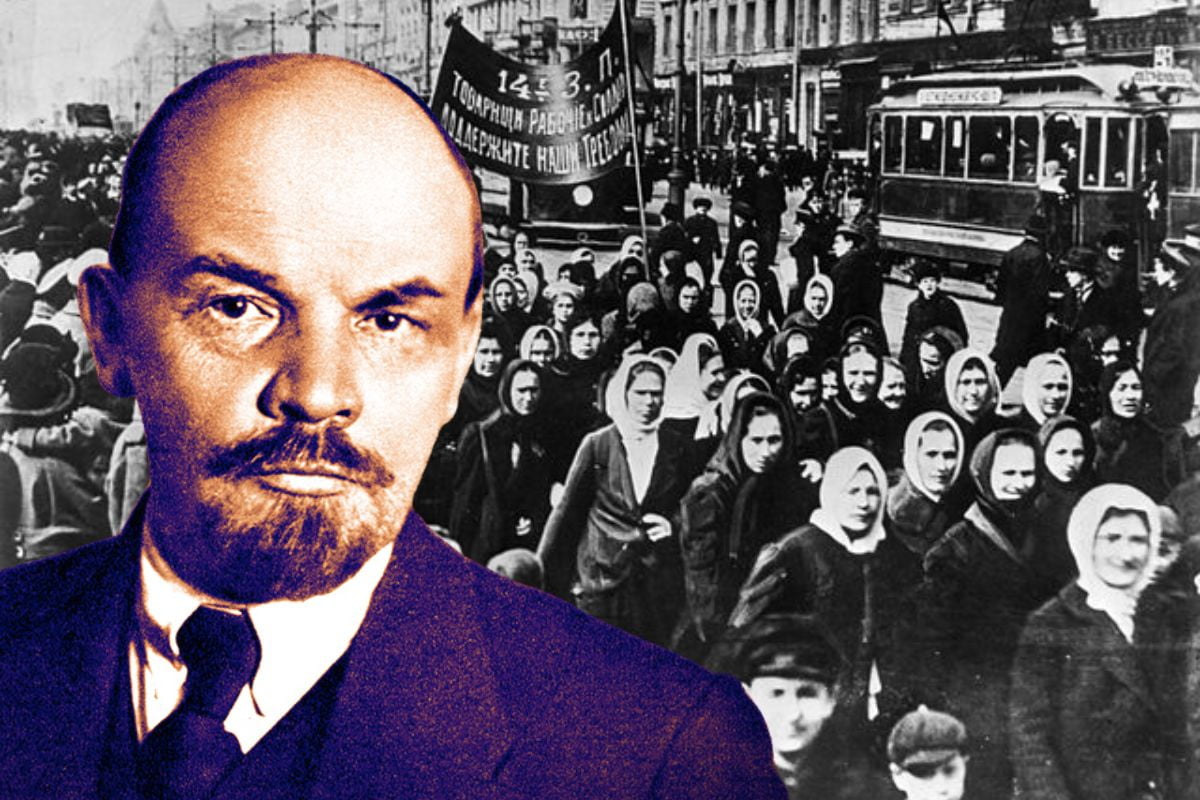

Lenin’s famous April Theses represented his fight to politically re-arm the Bolshevik Party, who had been swept off course by the February Revolution in 1917.

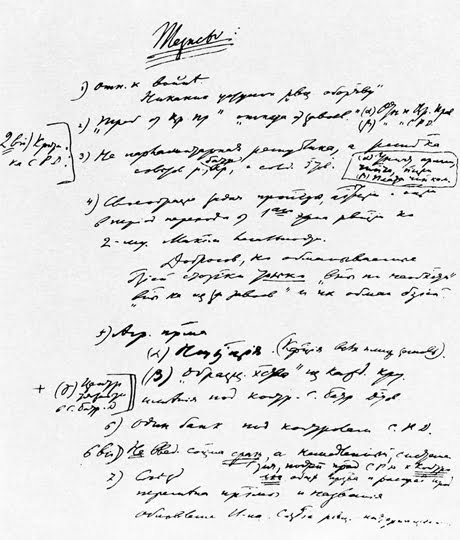

These theses were read out by Lenin at two meetings of the All-Russia Conference of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, on 4 April 1917 (in the old Russian calendar), and were published on 7 April in issue 26 of the Bolshevik paper Pravda.

They were nothing short of a political bombshell. At a time when the overwhelming public mood was of jubilation at the overthrow of Tsarism, Lenin soberly and systematically analysed the stage that the Russian Revolution was passing through, and declared the necessary steps to carry out a genuine and complete socialist revolution.

The April Theses called for revolutionaries to decisively break with the bourgeois Provisional Government, installed following the February Revolution, and to instead demand ‘all power to the soviets’ – the councils of workers and peasants that represented the embryo of workers’ power.

The response of the other Bolsheviks towards this declaration was utter shock. Lenin found himself in a minority of one amongst the Bolshevik Central Committee.

But such was Lenin’s political authority and genius, that he single-handedly managed to win over the Bolshevik Party to his political line. In doing so, he prepared the party to lead the working class to power in October of that year.

Were it not for Lenin’s intervention, the October Revolution would never have taken place. The entire course of history would have been altered. It was at this historical juncture where a great individual like Lenin could play a decisive role in history.

In case you weren’t aware, ‘In defence of Lenin’ is OUT NOW! Get your copy of the brand new, two-volume biography of Lenin. This is a genuinely Marxist analysis of the greatest revolutionary to have ever lived, it is essential for any communists today. https://t.co/hH7cGVnm7l

— Wellred Books Britain (@WellredBritain) February 6, 2024

Dual power

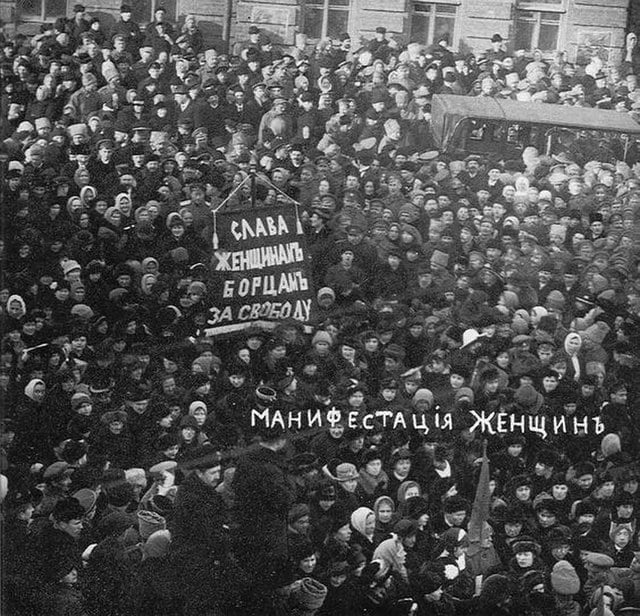

On 23 February 1917, a spontaneous strike of women textile workers in Petrograd initiated a wave of revolt. This would result in the overthrow of the detested Tsar Nicholas II within five days.

Protesting against the disastrous war campaign, the high cost of living, and terrible working conditions, the proletarian women of Petrograd mobilised the factory workers at a speed that surprised even the social democratic (which at the time meant Marxist) activists.

This was accompanied by mass meetings and demonstrations. By 27 February, most of the city was in the hands of workers and soldiers.

The masses, having learned from their experience of the 1905 revolution, immediately set up soviets: councils of workers and peasants.

In reality, the soviets held power in their hands. The leadership of the soviets, however, was in the hands of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries, who had no intention of taking power on behalf of the masses.

Instead, these leaders handed power to the bourgeois provisional government, consisting of liberals who ultimately represented the old regime of landlords and capitalists.

The intention of the Provisional Government from the start was to shipwreck the revolution. They merely made cosmetic changes at the top, without fundamentally changing society.

At one point, it was even revealed that the Provisional Government intended to re-invite the recently deposed Tsar back into power!

The lawyer and vice chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, Alexander Kerensky, was appointed as chairman of the new Provisional Government.

Ironically, Kerensky would have been considered far too radical for the Tsarist government in the preceding period. But as is often the case during revolutionary movements, out of desperation, the Russian bourgeoisie sought to incorporate this leader into their ranks, in order to restrain and placate the masses.

The Provisional Government made all the same arguments that the reformist leaders do today. They used their authority to hold back the masses, in the name of ‘unity’ and ‘defence of democracy’. They argued that it would be impossible for the working class to change society on its own, and that ‘pressure’ must be put on the bourgeois to make it act in the interests of workers.

A contradictory situation known as ‘dual power’ emerged in Russia. Two diametrically-opposed forms of government existed simultaneously: one representing the workers; one representing the capitalists.

Such a situation could not – and cannot – last indefinitely. Dual power is unstable and transitory, by its very nature, and can only ever be resolved by the complete victory of one of the mutually antagonistic classes over the other.

The longer this situation continued, therefore, the graver the threat to the revolution.

The Bolsheviks and 1917

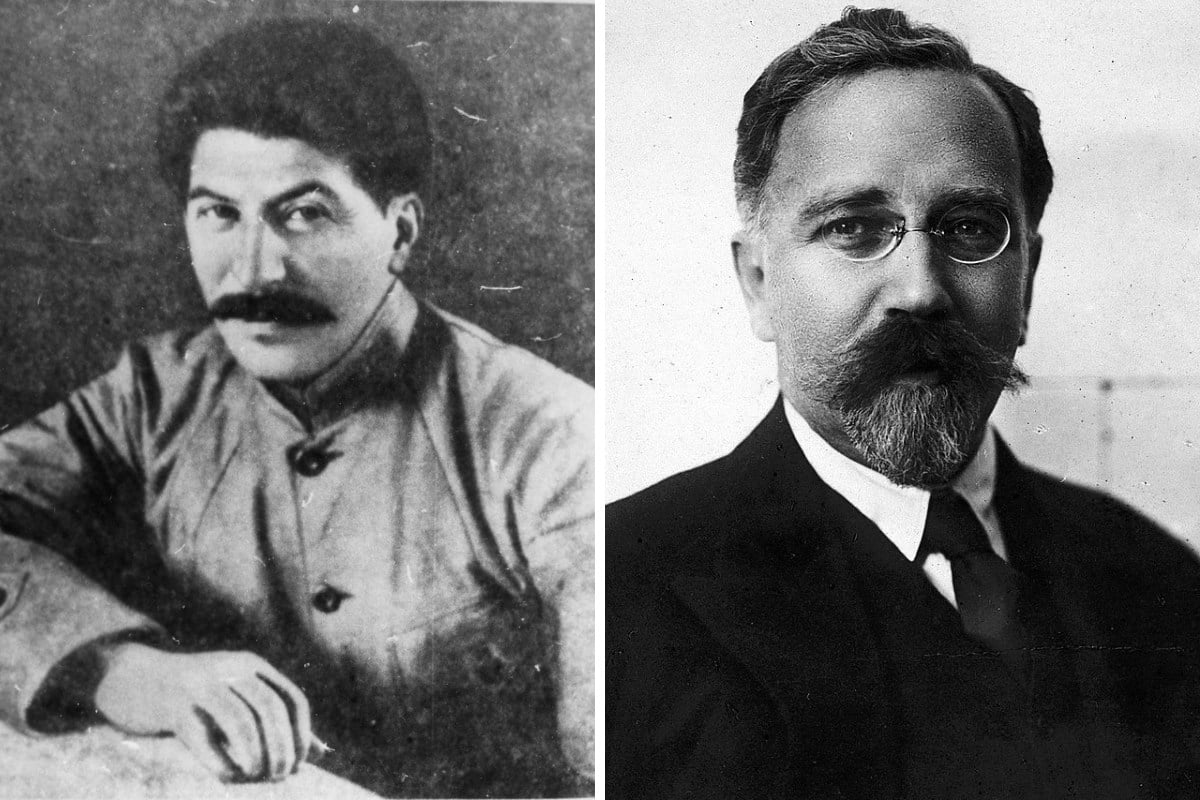

The February Revolution took all of the workers’ organisations by surprise. It had taken place whilst Lenin was in exile in Zurich Switzerland. In fact, all the main Bolshevik leaders were outside Petrograd at this point too. Stalin and Kamenev were in exile in Siberia, for example.

Upon hearing of the news of the revolution, Lenin immediately set about finding a way to return to Russia. In the country itself, meanwhile, the February Revolution freed political prisoners. And Stalin and Kamenev subsequently returned from Siberia. Ironically, this pushed the Bolsheviks further to the right.

The rank and file of the Bolshevik Party had a healthy, instinctive distrust of the Provisional Government. The leadership, however, represented by Stalin and Kamenev, whilst Lenin was still in exile, succumbed to the pressure of public opinion and the wave of naïve optimism that swept the country.

Pravda, the Bolshevik paper, refused to criticise the Provisional Government or its continuation of the imperialist war.

As is the case with every revolutionary movement, there was overwhelming pressure from the liberals for ‘unity’, which intoxicated the unprepared Bolshevik Party.

This even reached a point where, at the March Congress of the Bolsheviks, a fusion of the Bolshevik and Menshevik parties was actively considered by those present.

Letters from Afar

Lenin was shocked to hear of the Bolshevik response to the February Revolution. He demanded that workers break with the liberals and take power for themselves.

Notably, Leon Trotsky, who was in exile in New York at the time, had independently come to the exact same conclusion as Lenin.

It was in March 1917 that Lenin sent his letters from afar: the opening salvo in the struggle to re-arm the Bolsheviks, and the prelude to the April Theses.

In his letters to Pravda at the time, Lenin tried to bring the comrades to their senses as to the real situation that lay behind the euphoria over the Tsar’s overthrow.

He hammered home that the imperialist war could not be ended by the bourgeois Provisional Government, since the bourgeoisie were themselves tied by a thousand threads to the British and French imperialists, and had their own imperialist designs.

A lasting democratic peace – and not an imperialist, unjust one, which would merely pave the way for another war – could only be achieved with proletarian revolution abroad, as well as in Russia.

The Provisional Government was working towards the restoration of bourgeois power, he stated. No support should be given to it or the liberals. No unification should take place with opposing political parties like the Mensheviks.

The soviets represented the embryo of workers’ power, Lenin explained. But the majority of workers and peasants had to be united under a concrete programme, in order to carry out the practical tasks of the Russian Revolution, such as the nationalisation of the land and the banks.

And power would have to be transferred from the old state machinery, which was to be smashed, and handed to a new proletarian state.

The content of these letters could not have been more different to the official Bolshevik line.

The official Bolshevik leadership was so embarrassed by Lenin’s position, and its difference to theirs, that Pravda only published his first letter following heavy censorship to remove all passages where Lenin opposed agreement and unification with the Mensheviks. The second, third, and fourth letters were not even published!

Lenin rearms the Bolsheviks

After many negotiations, and a long journey back to Russia via Germany, Lenin finally arrived at the Finland station in Petrograd, where he was received with an enormous welcome by the Russian masses.

Upon his arrival, Lenin immediately turned his backs on the soviet leaders, who had turned up with flowers for him, and launched into a thunderous tirade against the Provisional Government.

From here, Lenin began a one-man struggle to turn the course of the Bolshevik Party around, under the famous slogan ‘all power to the soviets’. This was a struggle to prepare the Bolsheviks for power.

But what does the slogan mean?

The soviets were under the control of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries at this point. The Bolsheviks were a minority. None of the soviet leaders believed that the working class should be in power. Even the left Mensheviks, like Sukhanov, were of the same opinion.

The role of these leaders was to prop up the Provisional Government, behind which the forces of reaction were gathering strength and preparing for an offensive against the working class.

The essence of Lenin’s slogan was to argue that the liberal soviet leaders should in fact take power on behalf of the working class, despite the Bolsheviks’ minority position. Had the Soviets done this, it would have been a completely peaceful transition of power to the working class, without the later violence of the July Days and the Kornilov coup.

Lenin knew, however, that this was the last thing that the soviet leaders were prepared to do. The slogan was therefore intended to help win the masses over to the Bolshevik position – not by simply denouncing the leaders, who many workers still looked towards, but by showing the workers what their leaders could do – but were refusing to do – with the power of the soviets.

This both exposed these leaders, and showed to the workers that supported them that the Bolsheviks were not sectarian and only wanted the workers to have power.

April Theses

As Lenin explained: “The basic question of every revolution is that of state power.”

Lenin knew from the moment of its inception that the bourgeois Provisional Government was incapable of completing the Russian Revolution. It therefore had to be overthrown.

But he also understood that the Provisional Government only existed through the support of the soviets, which represented the will of the majority of the masses.

The task of the Bolsheviks, therefore, was to win a decisive majority of support amongst the masses and within the soviets.

But first, the Bolshevik Party had to be steered onto the correct course. Lenin’s ideas shocked the Bolshevik leaders, who were unable to assess the situation themselves.

Disunity and confusion reigned within the party. There was no clear position being provided by the leadership. Zinoviev, Kamenev, Stalin all opposed his ideas.

At a meeting of all the social democratic parties, Bogdanov declared Lenin’s one hour speech to be the “ravings of a madman”. Lenin was similarly denounced by Plekhanov, Milyukov, and all the social democrat leaders.

Lenin was, in practice, completely isolated. Undeterred, however, he attended the April Conference the next day, and outlined his theses in full. The following points were made:

- The Provisional Government, like the Tsarist one, is imperialist. The war being fought is therefore still an imperialist war. A revolutionary war could only be supported once the working class is in power. And without overthrowing capitalism, a truly democratic peace is impossible.

- The Russian Revolution is in transition from the first stage, where power was handed to the bourgeois class, to the second stage, where power must be placed into the hands of the proletariat and the poorest peasants.

- No support for the bourgeois Provisional Government. It must be exposed as “a government of capitalists”.

- The Bolsheviks are at this point a minority in the soviets. It is therefore necessary for a “patient, systematic, and persistent explanation” of the errors of the other parties, and of the need to transfer power completely to the soviets, which the masses will realise through experience.

- Not a parliamentary republic, but a republic of soviets of workers’, agricultural labourers’, and peasants’ deputies. No standing army but an armed people. Elected officials subject to recall and paid an average worker’s wage.

- Confiscation of all landed estates and nationalisation of all lands in the country, to be allocated by the soviets.

- Banks to be amalgamated into a single nationalised bank, under the control of the soviets.

- Bring social production and distribution of products under the control of the soviets.

- Call a party congress. Change the party programme on the imperialist war, the state, and the minimum programme, and change the name to the Communist Party. Lenin, seeing that the majority of social democrats had betrayed the proletarian revolution, understood the need to discard the soiled shirt of ‘socialism’, and adopt the clean linen of communism.

- A new revolutionary international. The Russian Revolution was never just a national event for Lenin – it was the beginning of the world proletarian revolution, which would be the only way of guaranteeing success in Russia.

Rigidity vs revolutionary

As Lenin points out, the masses are always more revolutionary than any revolutionary organisation. He therefore saved his fiercest remarks for the vacillating leadership of the Bolshevik Party.

Lenin threatened to take his criticisms directly to the ranks of the Bolshevik Party, if he remained in a minority in the leadership. The April Theses was published in Pravda three days later, bearing only Lenin’s signature.

The ‘old Bolsheviks’ responded by quoting Lenin’s old formulas by rote – formulas that had already been made redundant by events.

Kamenev replied to Lenin in Pravda, relying on the outdated formulation of a “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”. Lenin answered back decisively, stating that it was necessary to break with ideological routinism and face up to the reality of the situation.

Dual power in Russia meant quite literally that the bourgeois democratic revolution had been ‘completed’ with the handing of power back to the capitalists, through the Provisional Government; whilst at the same time, the embryonic workers’ state had emerged through the soviets, but had chained itself back to the bourgeois class.

The only possible outcomes were either complete counter-revolution under the Provisional Government, or a full transition to workers’ power, a soviet government, and the carrying out of the socialist revolution.

The old Bolshevik leaders treated Marxism as a rigid dogma, and a set of iron laws. They bent reality to fit the formulas, rather than the other way round.

Time and time again, old formulas and perspectives that have outlived their use must be changed or done away with, depending on the situation. As Lenin said: “Theory, my friend, is grey, but green is the eternal tree of life.”

Preparing for power

As the old Bolsheviks moved further and further away from him, Lenin’s ideas organically unified with that of Trotsky. Some of the Bolsheviks even accused Lenin of ‘Trotskyism’ in this period!

Completely independently of Lenin, Trotsky argued for the same thing as him: for the working class to take power in a second revolution. Arriving back in Russia in May 1917, Trotsky spoke and acted in complete solidarity with the Bolsheviks, joining them formally later in the year, delaying only to win over the 4,000-strong Mezhraiontsy group (with Lenin’s agreement) to the Bolsheviks.

Lenin’s appeal to the Bolshevik masses in the factories and the workplaces found an immediate echo. From there, his ideas reached the soldiers in the barracks.

Lenin’s ideas were endorsed at a Petrograd conference of the Bolsheviks. And after three weeks of short but sharp struggle, Lenin – from a position of complete isolation – had won over a majority of the Bolshevik Party to his position.

The April Theses and Lenin’s intervention to reorient the Bolshevik Party proved to be one of the decisive moments in Russian and world history. Through his political genius and authority, Lenin saved the Russian Revolution from almost certain disaster.

The Bolsheviks emerged from the April Conference as a unified and strengthened whole. From here, hundreds of thousands of workers joined the ranks of the party. The stage was set for the conquest of power.

The inaction and vacillation of the Menshevik and SR soviet leaders, however, led to the pendulum swinging towards the counter-revolution. Arch-reactionary general Kornlilov organised a coup – or rather, attempted to.

It was left to the Bolshevik workers to lead the successful struggle against the Kornilov coup. In the process, they won the support of a majority of the working class.

One by one the Bolsheviks gained majorities in every major soviet in the country, on the basis of their slogan ‘all power to the soviets’.

It was this that laid the foundations of the October Revolution, and the establishment of the first genuine workers’ state in history.