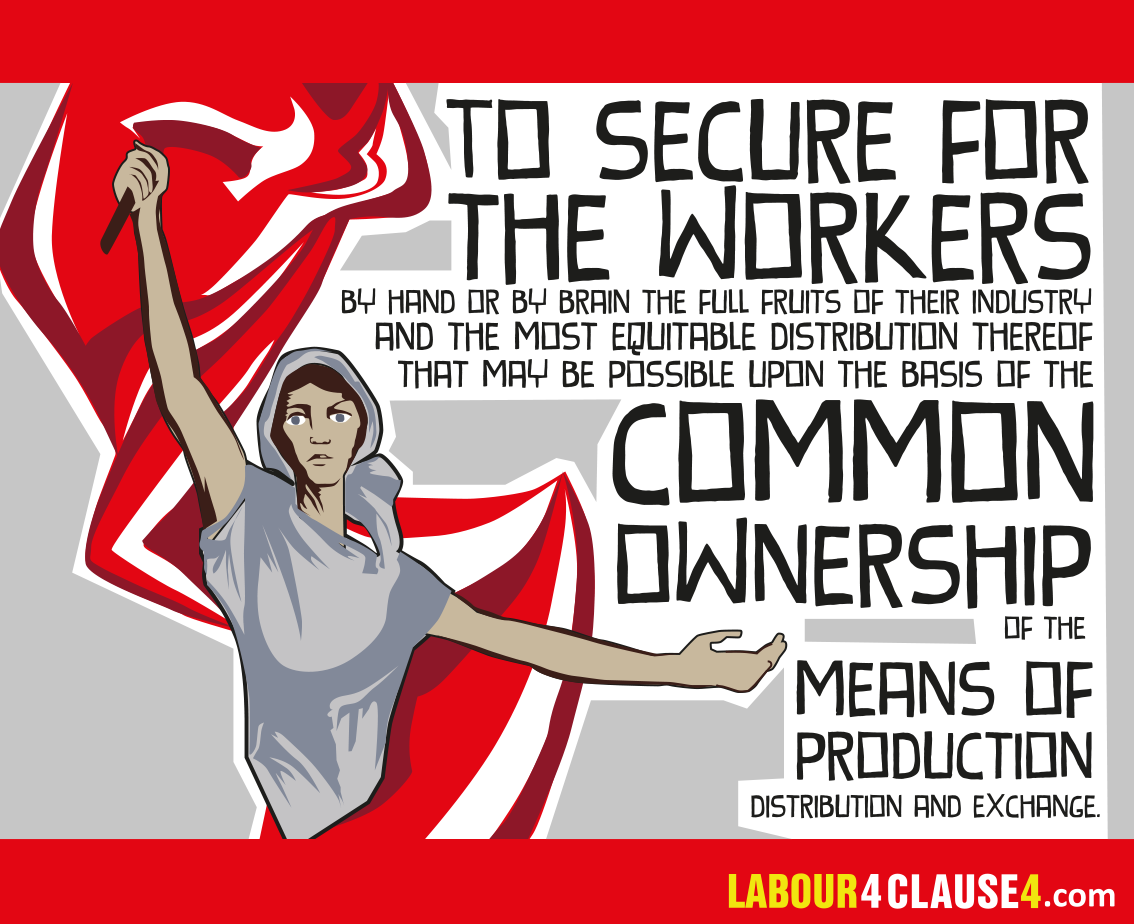

Today marks the centenary of the adoption of the socialist aims of the Labour Party. At a special Labour Party conference in February 1918 at Central Hall, Westminster, under the direct impact of the Russian Revolution, the party adopted a new constitution. This contained the famous Clause 4:

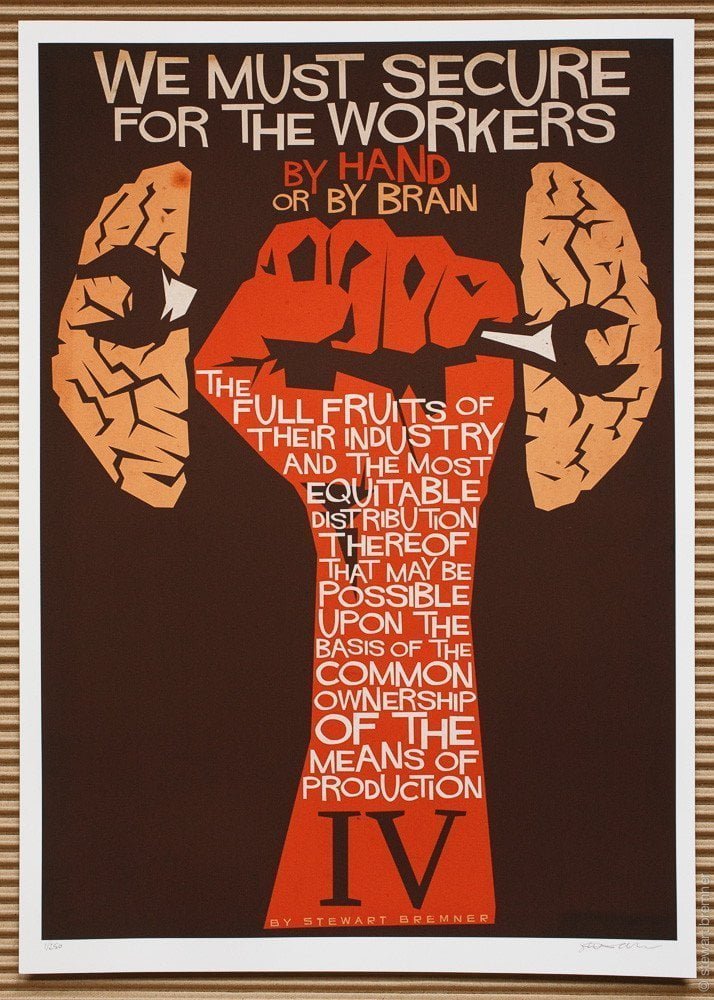

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.” (Clause 4, Part 4)

After nearly 20 years of Lib-Lab politics, the party finally expressed itself in favour of the socialist transformation of society.

One hundred years since its inclusion in the party constitution, and almost 23 years since its removal by Tony Blair, the discussion around its wording and meaning has become extremely relevant once again.

Add you name to the Labour4Clause4 campaign statement and help fight to commit Labour to socialism!

Revolution and radicalisation

What events led to the adoption of Clause 4?

What events led to the adoption of Clause 4?

Towards the end of the 19th century, it was becoming clear that the current political and parliamentary system was not working in favour of the growing proletariat. What became increasingly obvious to the millions of ordinary unskilled workers was that the Liberals were just another bosses cabal. As a result there was an increasing demand to create their own party – a party which truly represented their interests. In 1900, the Labour Representation Committee was formed. This was later renamed the Labour Party in 1906.

However, the party at its inception was not a revolutionary organisation, although it had in its foundations the general socialist aspirations of the working class as a whole. The Fabian outlook of almost all the main protagonists meant it had, as its main focus, a vision of parliamentary change only. It was felt that “socialism” could be brought into existence without the need for “revolution”. These reformist ideas of “gradualism” remained at the core of the Labour leadership.

The impact of the Russian Revolution challenged all that. The conditions arising from the bloodshed of the war and the victory of Bolshevism in Russia pushed the party to the left. Pressure was building up from below and through the ranks of the party for a more radical solution to the misery of the capitalist crisis and the slaughter of imperialism. With workers looking at the example of Soviet Russia, the capitalist system appeared on the brink of being overthrown.

This was the background to the adoption of Clause 4 by Labour and the movements that followed. The Manchester Guardian of 27th February 1918 heralded its adoption as showing “the Birth of a Socialist Party”, stating that:

“The changes of machinery are not revolutionary, but they are significant. There is now for the first time embodied in the constitution of the party a declaration of political principles, and these principles are definitely Socialistic…In other words, the Labour party becomes a Socialist party (the decisive phrase is “the common ownership of the means of production”)…Platonic resolutions have been passed before now, both by the Labour party and by the Trade Unions Congress in favour of the Socialistic organisation of society, but they are now for the first time made an integral part of the party constitution.”

In fact, it was more than simply “significant”. The Labour Party’s explicit aim was to be the replacement of capitalism with socialism. The clause was in fact first drafted by Sidney Webb in November 1917. Webb was a Fabian and therefore in his language he refused to recognise the class war. But the wording was clear enough in the context of what was happening in the world at the time.

In 1917, the whole of Europe was still enveloped in the massacre of the trenches, with revolutions, political and industrial movements beginning to break out. The most significant event to explode upon the world was the Russian Revolution. This was the first time in history in which the working class had come to power.

The significance of this event was not lost on the masses around the world. They looked in amazement at this achievement and saw within this revolutionary movement a potential future for themselves. The world indeed was moving through a new revolutionary upsurge which had not been seen since the days of the Paris Commune over half a century before. The consciousness of the working class was shifting on a world scale, something which terrified the ruling class but emboldened the workers.

“The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution,” noted Lloyd George. “There is a deep sense not only of discontent, but of anger and revolt amongst the workmen against pre-war conditions. The whole existing order in its political, social and economic aspects is questioned by the masses of the population from one end of Europe to another.”

Although unemployment had been mopped up during the war with the wholesale slaughter of the surplus labour on the battlefields, the conditions in the factories and the cities had not improved for those still living on the homefront. Poverty among the working population was still endemic and rumblings on the industrial front began to emerge. The initial jingoism and flag waving at the beginning of the war had worn off and a growing militancy was developing in Britain. Trades union membership had risen from 3,708,000 at the beginning of the war to 5,324,000 by 1918.

This strengthened the hand of all workers due to the short supply of labour on the one hand and the increased number of women in the factories on the other. With a third of the men at the front, the number of women in factories had risen by 670%. However, the war raged on, with hundreds of thousands dying in the trenches.

“Protest against any patching up of the old economic order”

This combination of factors had their impact upon the Labour Party, causing a sharp shift to the left.

This combination of factors had their impact upon the Labour Party, causing a sharp shift to the left.

The Labour movement had been enthused by news from Russia. The spirit of the times was captured by the British socialist paper, The Call on 29 November 1917:

“Socialists – genuine and not make-believe Socialists – have seized the reins of power…For the first time we have the dictatorship of the proletariat established under our eyes… The Bolshevik success has been carried out with the sympathy and support of the town workers and the common soldiers… Peace and bread, the suppression of the war-profiteer and the greedy landlord – this is what Lenin and his friends are trying to obtain for their own countrymen and for the distressed world at large. Are we going to help them?”

At the Labour Party’s Nottingham Conference in January 1918, there were unprecedented scenes of jubilation. The Bolshevik Litvinov, the representative of the Soviet government, received a standing ovation, amid cheers for Lenin and Trotsky.

However, the British government, together with the ruling elite internationally, regarded the Soviet government as a mortal threat to their system, to be eradicated as quickly as possible. In their struggle with the Bolsheviks, the imperialist powers gave unlimited support to the counter-revolutionary White armies.

In July 1918, the British dispatched an expeditionary force to Archangel and Murmansk to overthrow the Bolsheviks. In all, twenty-one imperialist armies of foreign intervention were dispatched against revolutionary Russia.

As soon as news of this became apparent, a protest movement mushroomed in one country after another, including in Britain. Here, the ILP issued a manifesto against the counter-revolutionary intervention of the British government. Later, a national “Hands off Russia” Committee led by Harry Pollitt and others was established and garnered support from all sections of the Labour movement. In March 1919, the Miners’ Federation demanded the withdrawal of British troops from Russia. The working class, demonstrating its internationalist instincts, rallied unequivocally to the cause of the Russian Revolution.

Within three days of the Armistice, in November 1918, an emergency Labour Party conference withdrew its ministers from the war-time Coalition and proclaimed its “protest against any patching up of the old economic order.”

The New Social Order

In the ensuing general election, Labour fought with a very radical manifesto, Labour and the New Social Order, specifically demanding:

In the ensuing general election, Labour fought with a very radical manifesto, Labour and the New Social Order, specifically demanding:

“The immediate nationalisation and democratic control of vital public services such as mines, railways, shipping, armaments, and electric power; fullest recognition and utmost extension of trade unionism…the abolition of the menace of unemployment…the universal right to work or maintenance, legal limitation of the hours of labour and the drastic amendment of the Acts dealing with factory conditions, safety and workmen’s compensation.”

It contained the appeal for a new society:

“The view of the Labour Party is that what has to be reconstructed after the war is not this or that government department, or this or that piece of social machinery; but, so far as Britain is concerned, society itself…

We of the Labour Party…recognise, in the present world catastrophe, if not the death, in Europe, of civilisation itself, at any rate the culmination and collapse of a distinctive industrial civilisation, which the workers will not seek to reconstruct…

The individualist system of capitalist production…with the monstrous inequality of circumstances which it produces, and the degradation and brutalisation, both moral and spiritual, resulting there from, may, we hope, indeed have received a death-blow. With it must go the political system and ideas in which it naturally found expression.

We of the Labour Party, whether in opposition or in due time called upon to form an Administration, will certainly lend no hand to its revival. On the contrary, we shall do our utmost to see that it is buried with the millions whom it has done to death.”

Although they did not win the election, Labour became the effective opposition, with two-and-a-half million votes (up dramatically from half a million in 1910) and a record 57 seats in the Commons. Its radical programme connected with the aspirations of millions of workers. It demonstrated the attraction of socialism. “The Party now adopted Socialism as its aim”, wrote Clement Attlee. “No longer is the mere return of Labour members sufficient.”

Unfortunately, the right wing leaders of the party (with the acquiescence of the lefts) deliberately ignored Clause 4. They wanted to bury it as soon as possible. But such was the support for socialism in the membership of the party, that they had to bide their time.

After the Second World War, the 1945 Labour government, elected with a landslide majority, carried through a certain programme of nationalisations but these were not of profitable industries but bankrupt ones. These measures posed no threat to capitalism.

In fact, the nationalisations – without workers’ control and management – but instead controlled by boards of bureaucrats, simply provided cheap coal, energy and transport to the profitable sections of the private sector. It did not bring in the socialist transformation of society as many thought at the time but served to save capitalism from itself for a whole period. Labour had wasted an opportunity to change society.

The rise of Blairism

Nevertheless, the right wing still detested Clause 4. The first major attempt to get rid of this socialist aim was by the right wing Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

Nevertheless, the right wing still detested Clause 4. The first major attempt to get rid of this socialist aim was by the right wing Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

After losing the 1959 general election, the right wing claimed that it was public opposition to nationalisation that had led to the party’s poor performance. Gaitskell announced that he proposed to amend Clause 4. However, the left-leaning rank and file of the party fought back and managed to defeat the change.

Symbolically, it was then agreed to include the text of Clause 4, part 4, on Labour Party membership cards, which stuck in the throats of Labour’s right-wing.

The swing to the right under Kinnock in the 1980s prepared the way for Tony Blair in the following decade. Blair openly stated that the split with the Liberals was a mistake, and so was the creation of the Labour Party. He therefore “renamed” the party New Labour and took measures in 1995 to abolish Clause 4 replacing it with more business friendly wording.

Blair succeeded where Gaitskell had failed. He later described it as a “defining moment in the history of my party.”

The scrapping of the clause represented a symbolic break with the Labour Party’s past and the arrival of the era of New Labour. Ironically, the decision to scrap Clause 4 was taken in the same Westminster venue where the old Clause 4 had been adopted in 1918. The next step was to try and break the link with the trade unions and turn the party into a Tory Party Mark Two.

Blair went quite far in his project. He almost destroyed the Labour Party. Under Blair, lefts were purged and the right wing dominated everything, concentrating power in the hands of a clique.

Now, two decades later, the tables have been turned. The election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader in 2015 (and again in 2016) was a political earthquake. Hundreds of thousands have joined the Labour Party, hoping to win back control. The tide has turned and the Labour right are very much on the defensive.

Capitalism has failed

Capitalism is today in a deep and fundamental crisis. The need for radical and socialist policies is inherent in the situation. The capitalist system has failed, which is clear to millions of people.

Capitalism is today in a deep and fundamental crisis. The need for radical and socialist policies is inherent in the situation. The capitalist system has failed, which is clear to millions of people.

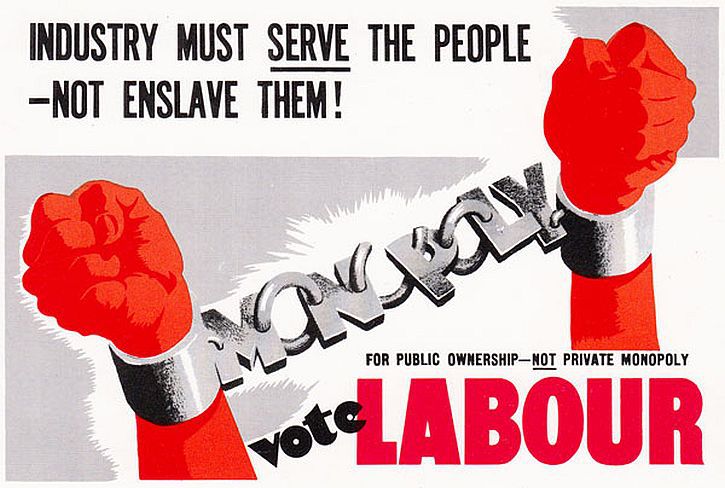

There has been a swing of opinion, after the experience with privatisation, towards nationalisation. Such is the demand for public ownership that even a majority of Tory voters support the renationalisation of key industries. A YouGov poll conducted in November 2013 put support for the renationalisation of the rail industry among Tory voters at 52%. The desire therefore to rid the UK of these parasitic private companies is rather palpable to say the least.

This is not surprising. With capitalism is in crisis, austerity is biting hard. There are no reforms, but savage counter-reforms. Sanctions on benefit claimants, zero-hour contracts, and continued attacks on living standards have all added fuel to a growing discontent within society.

The victory of Corbyn has opened the door to change. During the first Labour leadership contest in 2015, Corbyn gave an interview with the Independent on Sunday, which raised the possibility of restoring Clause 4:

“I think we should talk about what the objectives of the party are, whether that’s restoring the Clause Four as it was originally written or it’s a different one, but I think we shouldn’t shy away from public participation, public investment in industry and public control of the railways. I’m interested in the idea that we have a more inclusive, clearer set of objectives. I would want us to have a set of objectives which does include public ownership of some necessary things such as rail.”

This provoked a wail of protest from the Labour right wing and the Tory press. It had touched a raw nerve. Like a haunting spectre, it pointed to an alternative to the dog-eat-dog capitalist system. This is dangerous talk when millions are seeking a way forward. Such ideas can be contagious.

The subversive debate surrounding common ownership is now openly talked about, whereas in the past few decades nationalisation was considered a dirty word by some. The pendulum is swinging back.

Industrial unions used to have common ownership in their rules and constitutions. This still exists in the rulebook of the RMT union. Rule 4 (b) states as one of the union’s aims, “to work for the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”. The task is to change a rule into reality.

With regard to the historic task of the working class in its struggle with capital, common ownership has always been a key demand. Our call for the nationalisation, under workers control, of the top 150 monopolies is the bedrock of a socialist programme and chimes closely with what was enshrined in Clause 4.

“It is the task of the Labour Party”, wrote Clement Attlee in 1937, “to win over to its side all these elements which are still uncertain of their position. To do this involves a receptivity on the part of the Labour Party itself. It does not in my view involve watering down Labour’s Socialist creed in order to attract new adherents who cannot accept the full Socialist faith. On the contrary I believe that it is only a clear and bold policy that will attract their support. It is not the preaching of a feeble kind of Liberalism that is required, but a frank statement of the full Socialist faith in terms which will be understood.” (The Labour Party in Perspective)

The Labour movement, armed with a clear socialist programme based upon the common ownership of the means of production and full workers democracy, is the only way forward for humanity. Using state planning to bail out capitalism suits the ruling class when their system is in crisis. What we say is that a state plan, with the democratic participation of the working class at all levels, can bail out humanity and save it from any further ravages that capitalism can wreak.

A relentless and most determined struggle is now required by every class conscious worker and youth. The ruling class will not leave the stage of history without a fight. They must be shown the door and kicked through it! The working class are the clear majority and can lead the world toward the full socialist transformation of society. Clause 4 certainly points the way forward.