In February 1848, the workers of Paris overthrew their king and founded the Second French Republic. Months later they would rise again, in what became known as the ‘June Days’, which Karl Marx described at the time as “the greatest revolution that has ever taken place…a revolution of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie”.

The workers went down to defeat in June 1848. But their heroic struggle passed down a legacy and lessons which remain extremely valuable to workers of today.

The July monarchy

France in the 1830s and 1840s lived under the so-called ‘July monarchy’ of King Louis-Philippe. The regime was a hotbed of corruption.

France in the 1830s and 1840s lived under the so-called ‘July monarchy’ of King Louis-Philippe. The regime was a hotbed of corruption.

Through the ever-expanding national debt and the distribution of contracts for public works, the ministers “piled the main burdens on the state, and secured the golden fruits to the speculating finance aristocracy”, in Marx’s words. This state of affairs will feel very familiar to anyone living in Britain today.

The young working class was ruthlessly exploited under this ‘bourgeois monarchy’, often working 14 – or even 18 – hours a day, earning barely enough to survive. The lack of housing meant that workers and their families were crammed into tiny rooms, forced to live in the most squalid conditions imaginable.

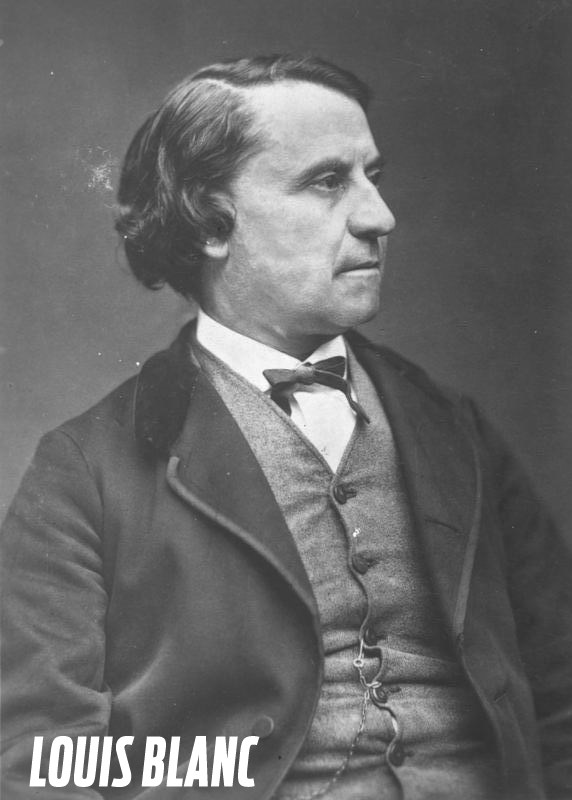

But it was also in this period that the workers began to forge their own organisations and education societies, where the ideas of socialism were eagerly debated. The most well-known socialist of the 1840s was Louis Blanc, who published his best-known work, The Organisation of Labour, in 1839.

Taking up the ‘right to work’ – an idea first put forward by utopian socialist Charles Fourier – as his slogan, Blanc called for the creation of ‘social workshops’ by the state, which would offer employment to all.

The February Revolution

France was rocked by a deep economic crisis in 1846 and 1847. In this context of instability, the liberal opposition resolved to strengthen its case for electoral reform by appealing directly to the people, or at least the respectable middle classes, who would stand to gain from their modest extension of the franchise.

France was rocked by a deep economic crisis in 1846 and 1847. In this context of instability, the liberal opposition resolved to strengthen its case for electoral reform by appealing directly to the people, or at least the respectable middle classes, who would stand to gain from their modest extension of the franchise.

The monarchy’s draconian anti-assembly laws, however, made it impossible for them to hold political meetings or rallies. Instead, they announced a campaign of ‘banquets’, in which attendees would pay an entrance fee to receive some food, wine for toasts, and then be harangued by a handful of well-known speakers.

The first banquet of the campaign took place in Paris in July 1847. Immediately, the campaign came under the influence of the more radical ‘Democrats’, who were supporters of universal suffrage.

As the campaign progressed, the workers were also drawn into the political struggle. But in addition to the vote, they also raised their own social demands, just like the British Chartists. At a banquet in Chartres for example, ‘the organisation of labour’ was raised as a demand alongside universal suffrage.

In parliament, the banquet campaign had done nothing to break the resistance of the government. In an atmosphere of escalating tension, liberal deputy Alexis de Tocqueville offered the following warning:

“This, gentlemen, is my profound conviction: I believe that we are at this moment sleeping on a volcano.”

When the authorities banned the last of the banquets, in Paris on 22 February 1848, this volcano erupted.

In the working-class districts of the city, arms shops were looted and barricades began to be built immediately. The next morning, the National Guard was called out to restore order. But instead they came chanting ‘Long live reform!’

The king dismissed the government, hoping to quell the revolt. But this only urged the masses on. When a column of protestors carrying a red flag pressed up against a line of infantry, the troops fired directly into the crowd. Fifty-two were killed on the spot.

The workers were enraged by the massacre, pledging, ‘Vengeance!’ From this point the fate of the monarchy was sealed.

By the next day the city was under the control of the armed working class. As the abdication of the king in favour of his nine-year-old grandson was being announced, the parliament was invaded by the revolutionary workers, who forced the proclamation of the Republic.

The workers betrayed

At all stages of the revolution of February 1848, the initiative belonged to the working class.

It was the workers who built and died on the barricades. And it was the workers who forced the proclamation of the Republic. But the class that was brought to power as a result of this workers’ revolution was not the working class. Nor did their representatives even obtain a majority.

The Provisional Government which was handed power on 24 February was overwhelmingly made up of ‘pure’, or ‘moderate’ republicans, with a couple of socialists like Louis Blanc tacked on under pressure from the workers.

The workers’ insurrection had placed its enemies in power. Leon Trotsky called this the “paradox of the February Revolution” in 1917, which applies just as well to February 1848.

On the streets of Paris, meanwhile, the armed workers remained the almost undisputed power. And having conquered the Republic, they naturally sought in it their liberation from poverty and oppression.

At noon on 25 February, day one of the new republic, a detachment of armed workers marched to the Hôtel de Ville. One of their number slammed the butt of his musket on the floor and demanded: “Droit au travail [right to work]”.

Blanc, seeing his own slogan menacingly thrust at him, immediately drafted one of the first decrees of the provisional government:

“The provisional government of the French republic pledges itself to guarantee the means of subsistence of the workingman by labour.

“It pledges itself to guarantee labour to all citizens.”

The same decree announced the creation of ‘national workshops’ to provide employment for all.

Overnight, the workers of Paris had effectively made Louis Blanc’s programme the law of the land, much to the surprise of its author. But Blanc himself was kept as far from the means to realise it as possible. Instead he was given a ‘commission’ to look into the question of the organisation of labour, without any power or budget to offer any practical solution.

Meanwhile, 100,000 unemployed workers were enrolled into the national workshops. But the task of finding and organising the work for this army of unemployed was given not to Blanc, but to Alexandre Marie, who was hostile to socialism.

Enrolled workers were given projects such as levelling the Champs de Mars. Employment on more useful projects such as building railways or canals was rejected by the government.

Unsurprisingly this arrangement pleased no one. Respectable society was scandalised by the sight of thousands of workers being paid public money in return for enforced idleness, while the workers themselves were bitterly disappointed.

For them, the ‘right to work’ signified not charity, but the organisation of production in order to guarantee useful work to everyone in accordance with their skills. What they wanted, in essence, was socialism. What they got was grimly described by Marx as “English workhouses in the open”.

The revolutionary clubs

One of the most inspiring products of the February Revolution was the club movement. The ‘clubs’ took their name from the clubs of the Great French Revolution. But they possessed a very different class content.

One of the most inspiring products of the February Revolution was the club movement. The ‘clubs’ took their name from the clubs of the Great French Revolution. But they possessed a very different class content.

Even the most radical clubs of the first revolution were a largely bourgeois affair. The clubs of 1848, on the other hand, were a cross between workers’ assemblies and political parties. They would meet regularly to discuss the pressing matters of the day, as well as questions of economic and political theory.

By mid-April there were 203 clubs in Paris alone, of which 149 were united in a single federation. They were essentially organs of workers’ democracy, growing rapidly out of the daily tasks of the revolution.

Marx described the clubs as “the centres of the revolutionary proletariat”, and even “the formation of a workers’ state against the bourgeois state”.

A key question for the club movement was that of its position in relation to the provisional government: should it support the government, albeit critically, or move to overthrow it? The majority of the Paris clubs took a conciliatory position, seeing their role as a support for and, if necessary, a check on the government.

The attitude of the Provisional Government towards the clubs, on the other hand, was more of fear and loathing, than surveillance and support.

So long as the armed workers were the main power on the streets, the Provisional Government would have to temporise, offering many concessions. But no one in the government had any illusions in this temporary state of affairs.

The government advances

The government was strengthened by the elections, which took place on 23 and 24 April 1848.

All Frenchmen over the age of 21 were eligible to vote for 900 deputies to a single National Assembly. This realised almost all of the political demands of the British Chartists, who had held a huge demonstration in London only weeks earlier.

The result was an overwhelming victory for the provisional government and the bourgeois republic. Almost every successful candidate ran as a ‘republican’ – including many monarchists! This showed the mood that existed in the country. But radical and socialist deputies only took up around 55 of the 900 seats in the assembly.

It must be remembered that the working class constituted a tiny minority of the French population at this time, and the vast majority of the electorate were peasants, living in the countryside.

A significant section of the peasantry would later shift violently to the left, but this would take time and experience. It was inevitable that at this stage the socialists would find themselves isolated.

The revolutionary workers in the clubs were disgusted by the result of the election, and began immediately calling for the overthrow of the assembly. Meanwhile, the government purged itself of its socialist members, Blanc and Albert, and prepared for war.

On 24 May, it was announced that the workers enlisted in the national workshops would either be drafted into the army or forced out of Paris.

The workers were faced with the dissolution of their organisations, deportation, and destitution. On 22 June, Louis Pujol, a lieutenant in the workshops, led a demonstration to the Ministry of Public Works and confronted the minister, Marie, who told them: “If the workers don’t want to go to the provinces, we shall make them go by force.”

That evening Pujol addressed a mass meeting at the Panthéon. “The people have been deceived!” he cried. “You have done nothing more than change tyrants, and the tyrants of today are more odious than those who have been driven out…You must take vengeance!”

The June Days

On 23 June, barricades began to rise in Paris. By noon, almost all of the eastern part of the city was under the control of roughly 50,000 insurgents – although the armed fighters were undoubtedly supported by an even broader layer of the working-class population.

On 23 June, barricades began to rise in Paris. By noon, almost all of the eastern part of the city was under the control of roughly 50,000 insurgents – although the armed fighters were undoubtedly supported by an even broader layer of the working-class population.

At the same time, the National Guard had been called out. But the response was extremely mixed. In eastern Paris, National Guardsmen allowed themselves to be disarmed by the workers or actively joined the insurrection. In the wealthier, western part of the city, however, the response to their orders was emphatic.

By eleven o’clock that evening, there were already 1,000 dead, with no end to the fighting in sight. All of the most prominent workers’ leaders either betrayed, or were killed, arrested, or in exile. Not a single socialist or radical deputy in the National Assembly supported the insurrection.

The ‘democratic socialist’ paper, La Réforme, explained, “We were ardent revolutionaries” under the monarchy, but “we are progressive democrats under the Republic, with no other code but universal suffrage”.

Louis Blanc signed a declaration calling upon the workers to throw down their “fratricidal weapons”, alleging they were “victims of a fatal misunderstanding”.

In theory, Blanc saw the democratic republic as a means of emancipating the working class. But in practice, his faith in the bourgeois state led him to defend it above all else, even against the very workers it was supposed to serve. This fatal flaw of reformism would return to haunt the working class time and time again throughout the world.

A state of siege was officially declared in Paris, and General Eugene Cavaignac was invested with dictatorial powers to defeat the insurrection.

Engels reported: “Today…the artillery is brought everywhere into action not only against the barricades but also against houses.” Many captured insurgents were shot on the spot and thrown into the Seine.

In contrast, in the areas under their control, the workers maintained perfect order. Only the gun shops were looted, and prisoners taken during the fighting were often set free.

New from Wellred! Series of 3 key writings by #Marx on France: ‘The Civil War in France’ – Marx’s analysis of the #ParisCommune – ‘The Class Struggles in France’ and ‘The 18th Brumaire’. Pre-order series for a discount price: https://t.co/OpARKUqyPH #ParisCommune150 #Socialism pic.twitter.com/SIOBsHFS6I

— Wellred Books (@WellredBooks) March 15, 2021

Defeat

Crucially, the workers fought alone. This fact, above all, determined the result.

The February Revolution had been led by the workers. But it was supported by a decisive section of the small property owners and artisans of Paris, who constituted the majority of the city’s population at the time. In June 1848, this ‘petty bourgeoisie’ sided with the defenders of private property against the workers.

In the meantime, up to 100,000 volunteers from the rural provinces were flooding into the city, travelling from as far as 500 miles away to fight against the insurrection. Blasted by explosive shells and surrounded on all sides, the insurrection began to retreat.

On the third day, the tide began to turn against the workers. And on Monday 26 June, the last barricade was cleared by Cavaignac’s troops. The Paris workers, isolated, without centralised leadership or artillery of their own, had held out for four full days against the full military might of bourgeois ‘civilisation’.

The government reported 708 casualties. The total number of insurgents was not accurately reported, but likely mounted into the thousands. Thousands more were deported to penal colonies in Algeria.

Paris had never seen such bloody fighting, which would only be surpassed by the crushing of the Paris Commune in the ‘bloody week’ of 21-28 May 1871.

What distinguished June 1848 from all previous insurrections was not only its scale. The June Revolution was arguably the first time the proletariat assailed the class rule of the bourgeoisie directly, in its own name.

That the workers and their leaders, experimenting and groping their way forward, made mistakes is undeniable; such is the lot of all pioneers.

This was still an early stage in the development of the working class. Not only was there no real party of the working class at this stage, even the trade union movement was under-developed and largely limited to specific crafts.

But that they came so close to victory, at a time when they constituted a minority even in Paris, let alone in the rest of France, is much more significant.

The workers had learned and achieved more in just over three months than in the preceding three decades.

Having won the democratic republic, the workers immediately sought to use it for their own ends. Blocked by the very institutions they had brought into being, they created their own democratic organs for the conquest of power and for the socialist transformation of society.

And in their defeat, the workers had passed down an immense revolutionary legacy.

Workers’ power

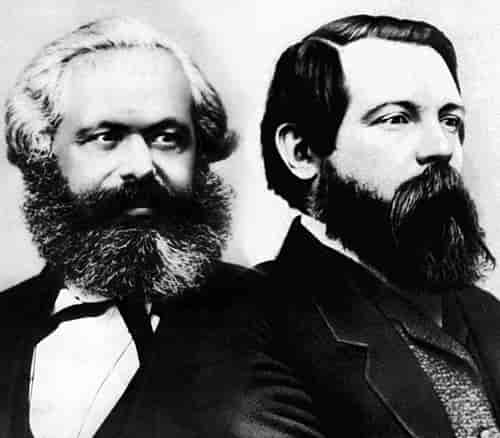

The titanic events of June 1848 also had an extremely important impact on the development of Marxism.

The titanic events of June 1848 also had an extremely important impact on the development of Marxism.

Drawing directly from the experience of the Paris workers, Marx issued an address to his organisation, the Communist League, in 1850. In it, he insisted that in a future revolution:

“Alongside the new official governments [the workers] must simultaneously establish their own revolutionary workers’ governments, either in the form of local executive committees and councils or through workers’ clubs or committees.”

Further, he explained that the aim of these councils or clubs should not be to support the official government, but to expose and eventually overthrow it, establishing what he termed “the dictatorship of the proletariat” – the class rule of the workers.

“Their battle-cry”, he concluded, “must be: The Permanent Revolution.”

Eventually, what June 1848 had only decreed in words was eventually carried out in practice by the Paris Commune of 1871: the first workers’ state in history.

These lessons were also studied carefully by Lenin and Trotsky, who applied them so successfully in 1917. It is therefore no exaggeration to say there is a direct link between the defeat of the workers in June 1848 and their victory in October 1917.

Today

These events still have a lot to teach us today. Global capitalism faces the deepest crisis in its history. Already, across the globe, the masses have toppled one government after another in search of a better life. And this is only the beginning.

In Europe, a level of corruption and malaise comparable to the last days of the July monarchy can be felt by all layers of society.

Like de Tocqueville in January 1848, the most farsighted representatives of the present order see the danger ahead. The volcano of revolution threatens to erupt once again.

But the modern working class is incomparably stronger than it was in 1848. And the possibility of the socialist transformation of society has never been greater. With a revolutionary leadership, guided by the lessons of history, its victory is assured.

Workers of the world: unite!