Over the past century, British capitalism has undergone an inglorious decline. What was once the world’s largest empire and most dominant power has been reduced to a third-rate power.

The reason for Britain’s success was its powerful industrial base. The British capitalist class invested their profits into revolutionising industry, making it the most competitive economy on the world market.

As a result, Britain produced the most powerful working class in the world. It’s not for nothing that Karl Marx considered Britain the most likely place for a socialist revolution.

With this power, the working class developed rich traditions. The first trade unions were formed in Britain, alongside the first political party of the working class – the Chartists. In the late 19th century, the Labour Party was formed as the political wing of the trade union movement.

In the 1970s, the world economy entered into a deep slump, intensifying international competition. British industry had fallen behind its competitors. To maintain profitability, the British capitalist class needed to attack workers’ wages and conditions.

The ruling class found their champion in Margaret Thatcher, entrusted to lead a decisive showdown against the working class.

The miners were the vanguard of the British working class. Thatcher, therefore, on behalf of the capitalists, deliberately provoked the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in order to decisively crush it, and to thereby demoralise and atomise the rest of the organised working class.

Deindustrialisation

Since the 1980s, there has been a rapid process of deindustrialisation in Europe, particularly in Britain.

From 1969 to today, those employed in manufacturing have fallen from 8.4 million to just 2.6 million. In 2022, approximately 360 people were employed in coal mines in the UK, compared to 247,000 in 1976 and a peak of 1.19 million in 1920.

Since the 1980s, there has been a dramatic hollowing out of British capitalism. The economy was taken over by coupon clippers, middlemen and gamblers – gouging their rents, interest, and commissions out of the value created in the production of real commodities elsewhere in the world.

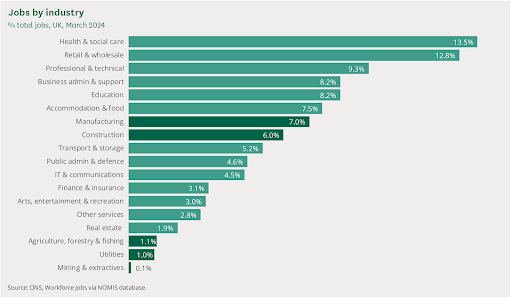

The service sector now dominates the UK economy, contributing 82 percent of GDP and employing 81 percent of the British workforce.

Pessimists on the ‘left’ have drawn the conclusion that the European and British working class either no longer exist, or are so atomised that they are incapable of leading a revolutionary struggle.

The facts, however, paint a different story. In fact, the working class today has never been more powerful – both in numbers and concentration in key sectors of production.

Furthermore, the actions of the capitalists and their representatives have discredited British capitalism and its institutions to a degree never seen before.

This has introduced unprecedented levels of instability and turbulence, reflected in the extreme levels of political polarisation and the collapse of the two-party system.

In the short-to-medium term, the capitalists may have succeeded in averting the immediate threat of revolution. In the long run, however, their actions have only laid the basis for its return on a much higher level.

What is the working class?

It is important to first clarify: what is the working class?

To be working class means that in order to make a living you have to sell your ability to work to someone else.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels referred to “the class of modern wage-labourers, who having no means of production of their own, are reduced to selling their labour power in order to live”.

What determines your class position is your relationship to the means of production. Those who own means of production are the tiny minority of capitalists – who, in turn, pay wages to the millions of workers who are put to work on these means of production, in order to produce a profit for the capitalists.

Workers produce all of the value in society. Yet they are exploited, receiving less in wages than what they actually produce.

Any value workers produce above that required to pay their own wages, Marx calls surplus value. This is the source of the capitalists’ profits. Profit is therefore the unpaid labour of the working class.

This class relation is the fundamental basis for exploitation – and therefore inequality – under capitalism.

The working class in Britain

With this in mind, we must ask: has the fundamental nature of the working class in Britain changed? Do they no longer sell their labour power? Do they now own productive property, meaning they no longer have to sell their labour power to survive?

In Britain, the largest proportion of jobs are in the health and social care sector (13.5 percent of all jobs) and the retail and wholesale sector (12.8 percent of all jobs), which includes supermarkets and associated industries. These both make up a portion of the ‘services sector’. The NHS is the largest single employer in Europe, employing close to 1.5 million people.

Surplus value is produced not just in factories, but in the whole process of production. Thus, a computer programmer also contributes to the final products of consumption. Similarly, a transport worker is essential to the overall process.

There are currently 33.98 million people employed in the UK – giving an employment rate of 75.0 percent for those aged 16-to-64.

In a 2024 business population report, the self-employed account for 12 percent of the working population. This should be taken with a dose of salt, however: many workers are made to register as self-employed so that employers have more power over them.

There are 5.45 million ‘small’ businesses employing 0-to-49 workers; 37,800 businesses are ‘medium-sized’, employing between 50-to-249 workers; and 8,250 businesses are ‘large’, employing 250-or-more workers. There are approximately 130,000 CEOs in Britain, managing the country’s medium-to-large-sized companies.

The extent of the ‘ownership’ involved in small businesses can vary widely: from owning shops and small-medium sized factories, to those driving taxis or electric delivery bikes. Even many healthcare workers – such as doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, etc. – are considered ‘self-employed’, yet the only ‘property’ they own is their ability to work for somebody else.

If we accept this figure, it still leaves 61.5 percent of people of employment age living in Britain being working class. Workers therefore make up the overwhelming majority of society.

Only a miniscule proportion of the population, meanwhile, could be said to own or manage significant amounts of capital – assets capable of generating surplus value.

When we put all these facts together, it is unsurprising that a majority of the population in the UK continues to consider itself working class.

According to the British Social Attitudes survey, for the period 1983-2012, the percentage of the population perceiving itself as working class has remained consistently around the 60 percent mark.

Qualitative strength

While manufacturing output as a share of world exports has dramatically declined, the productivity of labour in British manufacturing between 1999 and 2019 has actually doubled, meaning that the same amount of commodities can be produced with half the workforce.

Far from pointing to a weakening of the working class, the fact that workers produce more in less time has massively increased their power. For example, far fewer workers are employed in the energy sector than in the past.

This reduced number of workers objectively have immense power. They could paralyse the whole economy if they went on strike. Imagine if the electricity workers, gas workers, oil workers, together with the water workers, decided to strike in a coordinated manner. The whole economy would grind to a halt.

As communists, we base ourselves upon the working class – not for any sentimental reasons, but because of the crucial role they play in production, and because of the socialised character of their work, which gives them enormous power to change society.

When workers’ pay and conditions come under attack by the capitalists, they are forced to defend themselves by means of collective action – i.e. strikes, mass demonstrations, occupations, etc.

This is exactly what we are beginning to see in Britain now that the crisis of capitalism is intensifying.

In response to the increased cost of living after the COVID-19 pandemic, workers once again entered into struggle, taking collective action in the biggest round of strikes since 1989. Some of the most atomised workers in the hospitality industry have also begun to unionise and take action.

View this post on Instagram

Between 2022 and 2025, more than 1.4 million acute inpatient and outpatient appointments had to be rescheduled due to striking doctors and nurses.

Elsewhere, the Department for Transport commissioned a survey to analyse the impact of the rail strikes in 2022. They found that 81 percent of those who had intended to travel by rail during a strike week had their journey impacted in some way. Half of those who had planned to make journeys were unable to do so.

Refuse workers in Birmingham, meanwhile, are currently on an indefinite strike, leading to an unsustainable pile-up of rubbish across the city.

In the event of a general strike, the whole of society would grind to a halt. Who would supply the water, electricity, transport, postal service, internet, media, health services, construction of new infrastructure and buildings, and so on?

As Marxist theoretician Ted Grant once remarked:

“Not a wheel turns, not a phone rings, not a light bulb shines without the kind permission of the working class! Once this enormous power is mobilised, no force on earth can stop it.”

Aristocracy of labour

It is fashionable among some ‘lefts’ today to say that the ‘aristocracy of labour’ acts as a major brake on the proletarian revolution in the advanced capitalist countries.

This lack of faith in the working class leads to pessimism and mistakes of an opportunist and ultra-left variety. But is such an assertion true?

A lot has changed over the last century. Britain no longer has the privilege of being a global superpower, enabling the ruling class to ‘buy off’ a significant upper layer of workers, as it could in the past. In fact, since the 2008 crisis, there has been a relentless attack on wages and conditions for what were previously considered privileged ‘professions’.

A recent article in the Financial Times, entitled ‘The minimum wage is now coming for white-collar work’, stated that:

“In Britain, the fast-rising minimum wage is catching up with the bottom rungs of white-collar work. Indeed, it appears that a growing number of workers outside the traditional low-paid sectors are not even getting the legal minimum rate of pay.

“The latest report on minimum wage non-compliance from the Low Pay Commission, the independent body which oversees the policy, estimated the number of underpaid workers in non low-paying sectors had risen by nearly 40 per cent since 2019.”

The British Medical Association (BMA) estimated that between 2008/09 and 2021/22, junior doctors received a 26.1 percent pay cut. In 2021, meanwhile, pay for teachers was 8 percent lower in real terms than in 2007.

University staff pay has also declined in real terms, with some reports suggesting a drop of over 20 percent in the past decade. Even criminal barristers have seen a 35 percent reduction in income over this period.

This has led doctors, nurses, teachers, academics, barristers, and civil servants to take strike action in recent years – some for the first time in their history.

The government has introduced ‘physicians’ and ‘nursing’ associate roles, which have almost identical responsibilities to doctors and nurses. Training for these roles takes half the time, however, enabling the employers to drive down skills – and therefore wages and conditions – in a section of the workforce that historically was considered privileged.

Britain has been transformed into a low-wage, low-skill economy. Well-paid, skilled jobs are few and far between. Consequently, many graduates from ‘middle-class’ backgrounds are forced to take highly exploitative, low-waged jobs in the service industry.

An extraordinary one-third of UK graduates report being overqualified for their jobs, with figures from the OECD suggesting England has the highest rate of overqualified workers in the world, at around 37 percent.

Austerity and inequality

The ‘social wage’ workers in Britain receive includes free healthcare through the NHS, free primary and secondary education, state pensions, and unemployment benefits.

These, however, have been drastically stripped back since 2008 by austerity. If this wasn’t enough, Starmer’s Labour government has promised to make further eye-watering cuts to the welfare state, in order to increase military spending and make the working class pay for the crisis of capitalism.

All the while, the ratio of pay between CEOs and workers has widened astronomically. In Britain in 1968, the ratio of CEO pay to average national earnings was 30-to-1. Now that has widened to a ratio of 120-to-1.

The crisis of capitalism is drawing so-called ‘middle-class’ layers much closer to the proletariat.

In the past, these layers of the population acted as the social base for a stable bourgeois democracy in Britain – making up the bulk of the support for the liberal capitalist policies of the Conservative Party and the Labour right wing.

This explains the collapse of Britain’s two-party system. In recent months, we have seen the emergence of Nigel Farage’s brand of right-wing populism, alongside a surge in support for the Green Party.

The rug has been pulled from under the ‘centre-ground’ parties. Consequently, the British establishment is experiencing a political crisis, with polarisation to the left and the right.

This represents a collapse of legitimacy for bourgeois democracy – a necessary step in the development of class consciousness.

The emergence of parties considered outside of the establishment is a partial expression of a developing class consciousness, which will continue to mature as capitalism’s crisis deepens.

This will give rise to revolutionary explosions and upheavals in the period ahead.

Atomisation

Another popular argument for discrediting the possibility of revolution in Britain is that the working class have become totally atomised and alienated by the conditions of modern capitalism.

The argument goes that workers no longer work in industrial jobs, or live in areas with a strong community culture, and have thereby lost the traditions of struggle usually associated with ‘traditional’ working-class jobs. Again, this is only half true.

When Britain was a manufacturing powerhouse, entire towns and cities were based around particular industries: automobiles in Birmingham; shipbuilding in Glasgow; textiles in Manchester and Bradford; steel in Sheffield; mining in Durham, South Wales, and many other smaller towns mainly situated in the North of England.

In these areas there was a real working class pride in their industry. Even to this day, at the Durham Miners’ Gala, attendees proudly maintain and march with trade union banners that their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers carried before them.

Britain’s deindustrialisation has changed this. The closing of coal mines and factories transformed these once-thriving communities into ghost towns, scarred with high unemployment, poverty, and crime. This was especially the case in northern England.

Trade union membership in the UK reached its peak in 1979, with 13.2 million members, but has been declining in the long term. Between 1995 and 2023, the number of UK employees belonging to a union fell from 7.1 million to 6.4 million. Union membership as a proportion of all employees has also declined, from 32.4 percent in 1995 to 22.4 percent in 2023.

There is another side to this, however.

The trade unions might have been stronger numerically in the past. But they were also dominated by right-wing reformists – agents of the capitalist class, whose role it is to derail the workers’ movement down safe channels.

Leon Trotsky explained in his Writings on Britain that the slow and gradual development of capitalism in Britain “significantly improved the position of the upper layers of the proletariat and led its class movement along the peaceful course of trade unionism and to the liberal-labour politics that complemented it”.

The illusion that the lot of the working class could be improved indefinitely under capitalism was boosted by the postwar boom, an unprecedented capitalist upswing.

For almost twenty years, workers could apply pressure, and their leaders would meet the bosses and come to an agreement, usually ending in a wage increase and improvement in conditions.

This conditioned the psychology of the right-wing (and left-wing) bureaucrats who sat at the top of the labour movement. They saw their role as being mediators between the two irreconcilable classes.

In the 1970s, under Harold Wilson’s Labour government, “beer and sandwiches in Number 10” became a well-known phrase to describe the cushty relationship that trade union leaders had with the prime minister and the bosses.

But, when the global economic crisis hit in the 1970s, the bosses could no longer afford reforms. Increasingly, ‘beer and sandwiches’ meant union leaders selling out the workers and trying to sell a bad deal to their members. They posed temporary wage restraints as a means of ‘putting British industry back on its feet’. Needless to say, we are still waiting for that day.

Lenin explained that the leaders of the British labour movement have been particularly characterised by “their dislike of abstract theory and their pride in their practicality”. This ultimately did permeate down to the rest of the British working class.

View this post on Instagram

In Where is Britain Going?, Trotsky explains how:

“The proletariat itself is restrained by precisely its own top leading layer, i.e. the Fabian politicians and their yes-men…

“These pompous authorities, pedants and haughty, high-falutin’ cowards are systematically poisoning the labour movement, clouding the consciousness of the proletariat and paralysing its will. It is only thanks to them that Toryism, Liberalism, the Church, the monarchy, the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie continue to survive and even suppose themselves to be firmly in the saddle.

“[They] represent the most counter-revolutionary force in Great Britain, and possibly in the present stage of development, in the whole world.

“They are the main prop of British imperialism and of the European, if not the world bourgeoisie. Workers must at all costs be shown these self-satisfied pedants, drivelling eclectics, sentimental careerists, and liveried footmen of the bourgeoisie in their true colours.”

After decades of betrayals and carrying out the bosses’ austerity, the trade union and Labour bureaucracy have almost completely discredited themselves, beyond repair. Tony Blair is one of the most despised men in Britain, and Keir Starmer’s government is now probably the most hated in living memory.

This has left the door open for more left-wing leaders to take their place.

We saw the beginning of this process with the victory of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader in 2015, which demonstrated just how weak the right-wing bureaucracy was. Even at the height of the strength of the trade unions, the left never won the leadership of the Labour Party.

A similar process has occurred in the trade unions in recent years too, with the election of more left-leaning leaders like Sharon Graham and Mick Lynch in Unite and the RMT respectively.

Just this week, left winger Andrea Egan won the general secretary position in Unison – Britain’s largest trade union – in a serious challenge to the union’s entrenched right-wing bureaucracy.

The bureaucracy of the labour movement is now weaker than it has ever been. An important pillar of the British establishment is being steadily eroded.

Individual labour bureaucrats may be able to opportunistically place themselves at the head of this or that movement, and even gain a small amount of authority by talking in a radical manner. But this would be fleeting and temporary at best. The labour bureaucracy is objectively incapable of sinking deep roots in the working class, as in past decades.

The development of the class struggle in this period will therefore be much more explosive, and workers will draw political conclusions much more readily, breaking out of the confines of narrow, apolitical trade unionism.

In Britain, millions of people have come out onto the street to protest the genocide in Gaza. Similarly, in Italy in October, two million workers held a general strike under the slogan of ‘block everything for Palestine’.

A political general strike such as this is almost unprecedented in Europe. This provides a taste of what is likely to come in the not-so-distant future.

Many more explosive events like this are on the order of the day. And the official leaders of the labour movement will find it difficult to keep a lid on this fomenting situation as the pressure in society builds.

Although the atomisation of the British working class does present an obstacle for sustained industrial action – especially in precarious sectors with low union density – this is not an absolute barrier for the struggle of the working class.

Even if certain groups of workers are less likely than in the past to go through the traditional channels of the trade unions, they can – and will – undertake struggle, in whatever form that takes: wildcat action, mass demonstrations, social movements, and so on.

The job of a mass revolutionary party is to connect these struggles together, and fight for the unity of our class in the face of any objective and subjective obstacles.

Fertile ground

British capitalism today is in an existential crisis. For decades, the working class have seen a dramatic collapse in living standards, with even more brutal attacks to come.

Trotsky said that the myth of ‘capitalist progress’ had sunk deeper into the minds of British workers than anywhere else in the world. These illusions are now being shattered, along with any illusions in the right-wing Labour leaders, and the institutions of British capitalism.

The past period has seen a clearing of the decks, laying the foundation for a re-learning of many of the best traditions of our class – but on a much higher level.

The working class – especially the youth – are considerably less weighed down with the dead weight of past traditions and routines. They are increasingly open to radical and even revolutionary ideas, as seen in poll after poll.

In reality, despite the declarations of the naysayers, there have been few times in history so favourable to building a revolutionary party.

The problem will not be whether the working class attain a revolutionary consciousness – but whether we, the revolutionary communists, are big enough to capitalise on this when the time comes.