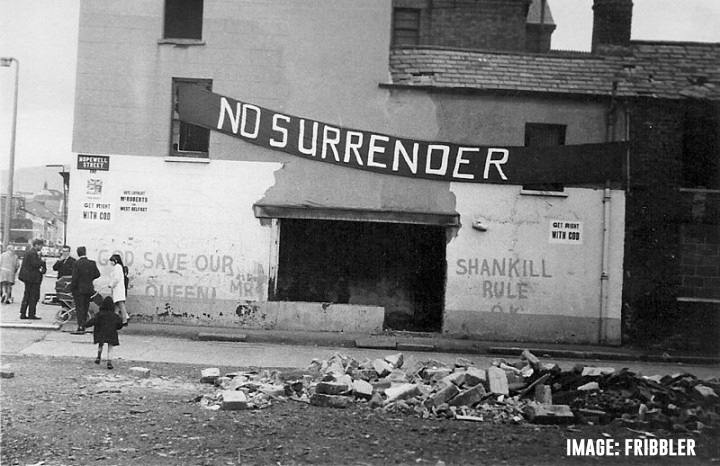

Loyalist rioting in the North of Ireland has raised fears of a return to ‘The Troubles’. This sectarianism is a Frankenstein’s Monster of British imperialism’s creation. Only a united class struggle for socialism can offer a way forward.

Over the past week, the North of Ireland has seen its worst rioting in years, ostensibly over the Northern Ireland Protocol signed by the Westminster government with the EU. The threat of loyalist violence has been in the air for months as tensions have ratched up since the Protocol came into effect in January.

Within weeks, loyalists issued death threats against port workers carrying out checks at the Irish sea border. At the start of March, the main loyalist paramilitary groups – the UVF, the UDA and the Red Hand Commando – took the step of announcing the withdrawal of their support for the Good Friday Agreement.

After all their threats, the loyalist paramilitaries have now bared their teeth. The immediate cause for the rioting was the refusal of the Public Prosecution Service to bring charges against senior Sinn Féin politicians for allegedly breaking COVID restrictions when attending the funeral of veteran Republican, Bobby Storey, on 30 June 2020.

The loyalists claimed that this was an instance of ‘two-tier policing’, with nationalists being treated with excessive leniency. The truth is that Catholics have been on the receiving end of heavy policing of COVID restrictions. Loyalist paramilitaries meanwhile have been treated with regular indulgence.

Nonetheless, this has served as the spark for loyalist rioting that has now been ongoing for a week. The numbers involved are small: groups of between a few dozen to a few hundred Protestant youths. They are disproportionately teenagers between the ages of 12 to 18.

One important detail – the mass text messaging and warnings to businesses – clearly show that this is no spontaneous affair. Behind the alienated, disillusioned youth, stand organised paramilitaries in one way or another.

On the sixth night of rioting (7 April) events took a serious turn. There were shocking scenes as a double-decker bus was pelted with petrol bombs and hijacked on Lanark Way, off the Shankill Road. The driver of the bus was assaulted and was fortunate to escape uninjured. On the same night, a Belfast Telegraph photojournalist was attacked from behind.

Most ominously of all, a car was rammed into the gates of a ‘peace wall’ on Lanark Way separating the Protestant community from the neighbouring Catholic Springfield Road. The gates of the ‘peace wall’ bore ironic artwork, stating, “There was never a good war or a bad peace”. The events of the past seven nights are precisely what a ‘bad peace’ looks like.

The hollow claim that sectarian conflict in the North had been ‘solved’ has been cruelly exposed. Nothing has been solved. The Good Friday Agreement pushed all the contradictions in the North of Ireland under the surface, where they festered only to burst out once more.

Explosives, fireworks and rocks were exchanged in the clash at the interface between Catholic and Protestant communities. Catholic youths naturally turned up – in self-defence – to face off against those bombarding their community. For the past couple of nights now, clashes have also erupted between police and Catholic youth. Now we’ve seen what ‘two-tier policing’ really looks like: the PSNI didn’t hesitate to unleash water cannons – banned in the rest of the UK – against nationalist youth.

The loyalist paramilitaries that triggered this violence have promised more – and a lot worse – to come. They’ve made clear that they will no longer cooperate with the Parades Commission when it comes to Orange marches.

A refusal to cooperate with the police is a very provocative gesture. It is essentially a threat to march through mixed and Catholic neighbourhoods in the summer marching season – a time when sectarian tensions are annually brought to a crescendo. It is a threat to unleash havoc across the region.

What is the logic of the past week of violence? In themselves, the loyalist rioters represent small numbers. They are threatening, however, to throw a match into a heap of sectarian inflammable material if they don’t get what they want.

Their central demand is for the Northern Ireland Protocol to be scrapped. They are blackmailing politicians in London, Dublin and Brussels that if they don’t get what they want, they have the power to create chaos and drag the region back to the ‘bad old days’.

A creation of British imperialism

The blame for the chaos on the streets of Ireland today must be placed squarely at the feet of British imperialism. For centuries, British imperialism has used sectarianism to divide the Irish working class.

The blame for the chaos on the streets of Ireland today must be placed squarely at the feet of British imperialism. For centuries, British imperialism has used sectarianism to divide the Irish working class.

One hundred years ago it whipped up pogroms and partitioned Ireland in two to serve its short-term aim. It is still living with the legacy of that decision. Having unleashed the forces of sectarianism, those forces are now out of its control.

The deepening crisis of British capitalism is further inflaming the situation, and loyalist sectarians are making the most of it to bolster their support. The crisis is making life very hard for millions.

140,000 children already lived in poverty across the North prior to the crisis. Workers in both communities feel ignored and left behind. There is a feeling of insecurity – a feeling that the future holds nothing positive for working people. Sectarians in Protestant communities have attempted to channel this general feeling of bitterness, alienation and insecurity into a siege mentality.

They are warning Protestant workers that they are surrounded by enemies; that the British government is happy to bump them into a united Ireland against their will; that they will have to fend for themselves; that they are under threat of becoming second-class citizens in a United Ireland, etc., etc.

Out of the crisis of capitalism, the struggle over the crumbs intensifies. In this poisonous soil the seeds of racism and sectarianism are allowed to germinate. In fact, the unionist politicians have no choice but to encourage these poisonous seeds.

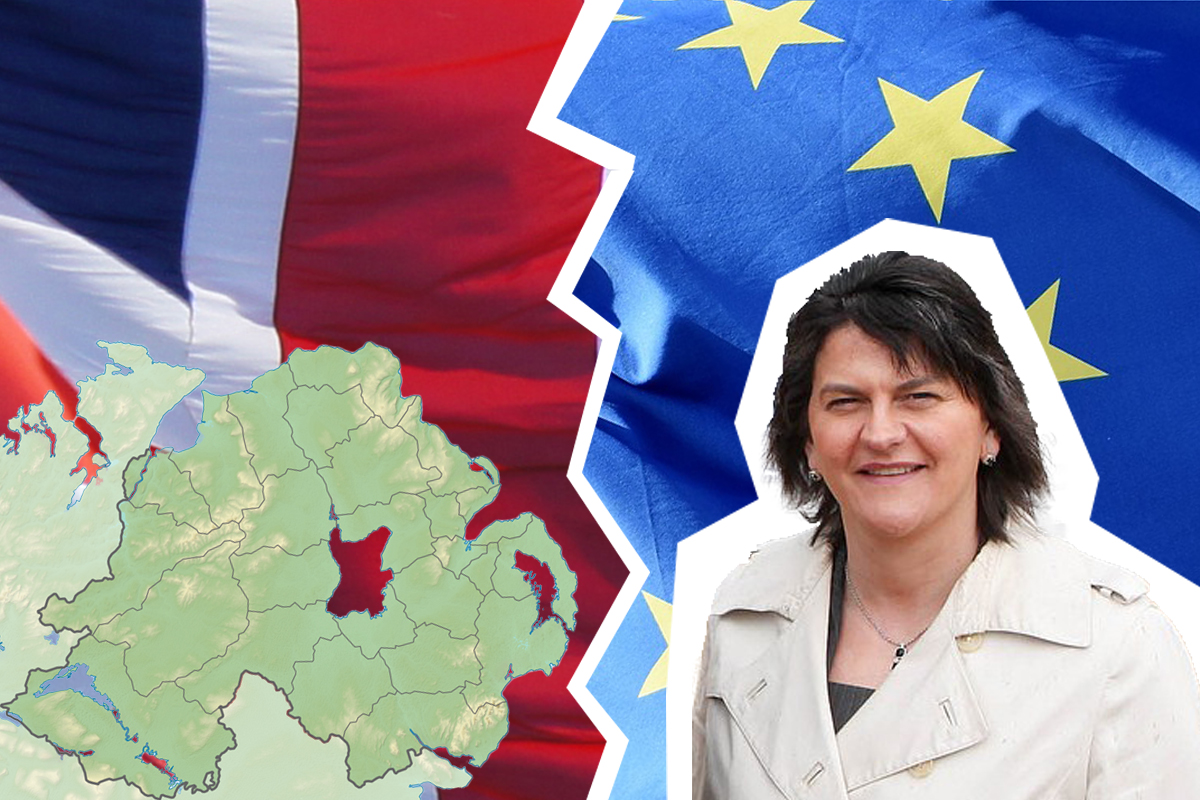

In decades past they could shore up their support with economic concessions to a layer of Protestant workers. But in today’s climate of austerity, all the likes of the DUP can offer is to ratchet up sectarian fear-mongering – to build that siege mentality and then put themselves forward as the best defender of Protestants and the union.

Into this toxic mix, the myopic representatives of British capitalism introduced the black and white choice of the Brexit referendum. With the Tory Party coming apart at the seams, David Cameron staked everything on an EU referendum in 2016, hoping ‘Remain’ would win.

The more desperate the British capitalist class became, the more inclined they have become to wild political gambles. But until 2017, not a single speech was given, nor a single line written, about the consequences Brexit would have in Ireland. They didn’t give it their first thought.

In the North of Ireland a majority of Catholics voted to remain, while a majority of Protestants voted to leave. But, as in Scotland, an overall majority voted to remain. The Tories all promised, however – Johnson included – that the UK would leave the EU as a single unit. And yet in January, Boris Johnson delivered a Brexit deal that sees the North of Ireland remaining in the common market.

From the beginning though, Ireland was an impossible problem to solve on a capitalist basis. A capitalist EU cannot tolerate a hole in its border. However ‘light’ that border is, it must protect its internal market from its competitors. They therefore require either a border in the Irish Sea, or a border on the island of Ireland.

In fact, the English nationalist ranks of the Tory Party didn’t particularly care what happened to Ireland. Frankly, Boris Johnson doesn’t either, as evidenced by his initial promises not to introduce a sea border… and the fact that he then introduced a sea border.

Inevitably, the NI Protocol was met with cries of, “Betrayal!” from hardline unionists and loyalists. Even Boris Johnson himself, in his bumbling, demagogic fashion, has taken pleasure in using the economic, social and political chaos caused by the Protocol in its short period of existence as a stick to beat the EU with.

The Tories were happy to court the DUP when it suited them; they were happy to whip up British nationalism and unionism when it suited them; they were happy to threaten to use Article 16 and suspend the NI Protocol when it suited them. Now they must find a way to live with the consequences of their actions.

The idea that their communities are left behind, ignored and betrayed has been encouraged by unionists and reinforced by the actions of British imperialism. Now the loyalist paramilitaries are using this anger to mobilise hot-headed, semi-lumpen youth, as a threat to the British. Their threat is simple: back down from the NI Protocol or watch us set a fire in your back garden.

But whilst the British might try to reopen negotiations with the EU, and the government in Dublin might try to broker some concessions, the Brexit dilemma remains insoluble. Either Boris accepts the sea border and the NI Protocol; or he ditches it. But ditching it means souring relations with the EU and the United States, only to see the sea border replaced with a land border.

Boris is of course notoriously stupid and shortsighted. But because of the need for the British capitalists to maintain some access to the EU market, it is hard to imagine he will bend to the loyalists’ demands. In which case, a head-on collision and further violence becomes the most likely outcome.

Unionism, loyalism and the sea border

The NI Protocol has become the catalyst for a crisis of many years in the making for unionism and loyalism. This Protocol is symptomatic of the uncomfortable truths they are now facing. Over the last few years unionism has lost its majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly. Recent polls suggest there is growing support for a united Ireland.

The NI Protocol has become the catalyst for a crisis of many years in the making for unionism and loyalism. This Protocol is symptomatic of the uncomfortable truths they are now facing. Over the last few years unionism has lost its majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly. Recent polls suggest there is growing support for a united Ireland.

Partly as a result of demographic changes and partly as a result of the crisis in unionism, the likelihood of a Sinn Féin First Minister after the next Assembly election is growing.

Unionism is cringing with apprehension at the results of the recent census. It is very possible it will reveal a Catholic majority, or at least a strong Catholic plurality, whilst Catholics have been a majority at all levels of education and in work for some time now.

Unionism has been plunged into crisis for some years. Its majority has slipped away, its politicians are hated in the Protestant community. The UUP – once dominant on the political landscape – has collapsed. The DUP, which supplanted it, senses that the ground beneath its feet is not stable either.

The DUP has been haemorrhaging support to the even more right-wing and reactionary TUV, which has always been on the fringes but which now stands at 10% support in the polls. The same poll put Sinn Féin six points ahead, and Alliance (a liberal, anti-sectarian party) one point behind the DUP. The panic this caused in the DUP’s own ranks was clear from leaked minutes of a meeting of party members in South Antrim.

The minutes lamented how “unionism has lost ground”, and noted that anger in the “Unionist/Loyalist” community is at “boiling point”. The sectarian anger it has carefully cultivated as the basis for its support is now beyond its control. The Tories were happy to court the unionists when it suited them. And the DUP have been happy to court the loyalist paramilitaries in turn. They made for useful foot soldiers in elections, even intimidating opponents out of the race. But as a commentator in the Belfast Telegraph noted:

“It did political unionism no harm at all to have an angry barking dog in the corner of the room when they were attempting to put pressure on the British Government over the Brexit protocol.

“But as we discovered last week, that angry dog is difficult to control when let off the leash.”

The crisis of unionism, the rise of Sinn Féin in the North and South, and the implementation of the NI Protocol have convinced many loyalists and hardline unionists that the time is ‘now or never’ to make a stand.

The loyalist paramilitaries themselves are by no means a centralised, single voice. The Loyalist Community Council has been at odds with itself over how to respond to the rioting, and may now fracture entirely.

Among the loyalists there are older ex-paramilitaries who have no interest in taking up the gun. There are lumpen, criminal, drug-dealing elements that have become particularly dominant among paramilitaries. They have their own reasons for baring their teeth at the police.

And there are those who form a hardcore of mad men who are prepared to stir up pandemonium and who are appealing to the most alienated layers of Protestant youth.

No future under capitalism

What has the response been in Catholic communities? Understandably, many Catholic youth have turned up at the interface areas to confront those throwing stones and fireworks over the ‘peace walls’ into their communities.

What has the response been in Catholic communities? Understandably, many Catholic youth have turned up at the interface areas to confront those throwing stones and fireworks over the ‘peace walls’ into their communities.

Some have called for Catholic youth to go home so as not to encourage a cycle of violence. They underscore the danger of throwing projectiles back – that it might play into loyalist hands by injuring bystanders – without offering an alternative defence strategy.

But these calls are clearly not going to be listened to, as it would mean simply standing idly by while they are under serious physical attack, while their homes are pelted by missiles.

Neither is sitting at home a guarantee of safety. If loyalist hooligans ever were to succeed in breaking through the ‘peace walls’ into Catholic communities, petrol bombs would end up being lobbed through home windows and people would be killed. The PSNI certainly won’t protect Catholic neighbourhoods.

Worse than useless perhaps are those – such as Sinn Féin – who call upon the leaders of ‘political unionism’, and even loyalist paramilitary leaders, to ‘act responsibly’ and cool things down.

The DUP are driven by their own agenda. They know what they are doing when they pander to sectarianism. When Arlene Foster condemns rioters for distracting from the crimes of Sinn Féin, she knows what she’s doing too. They are enemies of the working class, both Catholic and Protestant. Appealing to them is like appealing to Beelzebub against Lucifer!

Sadly there is a similar logic in the labour movement. The only non-sectarian, working-class organisations in the North of Ireland that could potentially cut across the morass and put forward a clear class alternative are the trade unions.

We’ve seen a marvellous demonstration from the bus drivers of the solidarity and potential authority the organised working class could muster in both communities.

After the petrol bombing of a translink bus, hundreds of bus drivers surrounded Belfast city hall with buses and held a protest in which they vowed not to drive through disturbed neighbourhoods after a certain time at night. No less than 13,000 people liked the Belfast Live livestream of the protest. Typical comments were along the lines of “these bus drivers are showing more leadership than the politicians combined”.

The trade unions could offer a lead. They could call political strikes to isolate the loyalist rioters. They could organise non-sectarian self-defence to patrol neighbourhoods. Indeed, the Irish working class has a glorious tradition of organised working-class self-defence, from Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army, to the incipient development of a Trade Union Defence Force in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Yet the majority of the trade union leaders are explicitly non-political. They adopt an apolitical position mistakenly in the belief that only by removing politics from the trade union movement is it possible to cut across the sectarian divide.

But when workers are attacked by loyalist thugs, to whom do these ‘apolitical’ trade union leaders appeal? To ‘the politicians’! The representatives of ‘political unionism’ must cool things down. But this has a sectarian logic of its own.

The unionist politicians and loyalist paramilitary leaders have no right to speak for Protestant workers! It is only because there is no independent working-class voice, because the trade unions do not speak for workers, that right-wing sectarians can falsely claim to be their voice.

A revolutionary trade union leadership would call for political strike action against loyalist provocation and would proactively organise self-defence. The problem is precisely the lack of such leadership. In its absence the situation will remain volatile.

No one, other than a tiny fringe, wants to return to the violence of the past. But in 1968, the first of Ian Paisley’s counter-demonstrations against the Civil Rights movement were relatively tiny. Yet they acted like a spark against a powder keg.

The mood can change very quickly if lives are lost. It can turn into a mood of revulsion towards the instigators of the violence – and it can also turn into moods for revenge.

We are living through a critical moment in Ireland’s history. The decay of British capitalism has revived the ghosts of the past and pushed Ireland once more to the brink. It is tempting in these moments to imagine there are shortcuts. There are none. Under capitalism, the dangers of renewed violence, bloodshed and even civil war will be ever present.

The organised working class has the power to bring the violence to an end. We have seen a glimpse of this power with the bus drivers.

In recent years we have seen other demonstrations of this power and the sympathy that organised workers can inspire in all working-class communities: from the strikes of nurses over pay and conditions; to strikes of meat factory workers over safety.

COVID in particular has sharply focussed attention on the real divide in society. Whilst the bosses, the Tories and the DUP were united in rushing to open the economy up, workers in all communities understood that they had a common interest in uniting to fight the virus.

The DUP tried to play sectarian football with COVID. Edwin Poots even tried to paint it as a ‘Catholic virus’.

The real divide was not Catholic versus Protestant, but the workers against the bosses who have tried to turn them into cannon fodder for their profits.

However ominous the situation appears, and however hard it seems to bridge the sectarian divide in the North of Ireland – difficulties that can hardly be understated – we must bear in mind that events in Ireland are not sealed from events in the rest of the world. Class struggle is on the order of the day: in the South of Ireland, in Britain, and across the world.

At the moment the COVID-19 pandemic is holding back worker protests. But class anger is building up in both Britain and Ireland. Workers in the North, both Protestant and Catholic, face the same problems.

The healthcare workers, for example, have been placed under immense stress and strain, and have been granted a miserable reward in terms of wage increases. Unemployment is growing, small businesses are going bust.

All this means that when workers in the South or workers in Britain begin to move on the concrete issues that affect ordinary working class people, this will inevitably have an impact on workers in the North of Ireland.

These inevitable mobilisations will ignite the imagination of working-class youth in both Catholic and Protestant communities. Therein lies the perspective of united working-class action.

The bulk of ordinary working-class people do not want a return to ‘The Troubles’. But the fact that most people don’t want it is no guarantee that it will not return. Capitalism in crisis creates the conditions for heightened tensions, that reactionary politicians will exploit to pit worker against worker.

It is the duty of Marxists in the North of Ireland to explain why all this is happening, and why it is happening now. They must warn the workers of where all this could lead. But they must also offer an alternative perspective – one of united working-class struggle against the very system that spawned the sectarian monster: capitalism and imperialism.

According to the artwork on the Lanark Way ‘peace wall’: “There was never a good war or a bad peace.” We have to disagree on two counts. There is a ‘bad peace’. We are living through it. And there is a ‘good war’: the class war to put an end to the capitalist system, the source of misery, poverty and sectarianism.