Ben Curry reviews Peter Hadden’s book on the history of the class struggle in Ireland, and asks: how should Marxists approach the national question?

Peter Hadden was still working on the finishing touches of his book, Common History, Common Struggle, when he sadly passed away in 2010. In it he analysed the events surrounding the beginning of the Troubles in Ireland. What began as a mass uprising of working-class, Catholic neighbourhoods eventually descended into a reactionary spiral of violence.

Clashing head on with counter-revolution, the movement (or more precisely, the leadership of the movement) proved unprepared for the turn of events. As a result, the period from the mid-1970s to the 1990s was dominated by tit-for-tat sectarian conflict and a struggle principally between the IRA on the one hand, with its methods of individual terror, and the British state and loyalist paramilitaries on the other.

The subtitle of the book summarises its central theme: “when workers’ unity & socialism challenged unionism & nationalism”. Hadden’s intention, of highlighting the role of the working class in these events, is noble enough. But his conception of “workers’ unity” at times becomes quite abstract. Throughout, unionism and Republicanism are incorrectly placed on the same plane by Hadden as two equally reactionary camps. Persisting in what was largely an error of emphasis, the Socialist Party of Ireland (SP), to which Hadden belonged, has today found itself mired in the swamp of opportunism.

A carnival of reaction

Hadden begins by giving a history of partition in Ireland. He shows how the British partition of Ireland, driven by a fear of Bolshevism, resulted in a “carnival of reaction”, North and South:

Hadden begins by giving a history of partition in Ireland. He shows how the British partition of Ireland, driven by a fear of Bolshevism, resulted in a “carnival of reaction”, North and South:

“Through partition the British ruling class succeeded in inflicting a serious defeat on the workers’ movement in Ireland. In the process they established an artificial and inherently sectarian state in the North and acceded to the formation of a semi-independent, clerical and reactionary state in the South.” (Common History Common Struggle, Hadden p62)

In the North, brutal repression, discrimination in jobs and housing, gerrymandering, and a host of other vile means were used to keep Catholics under the heel of the unionist bourgeoisie and British imperialism. In the South, as Hadden explains, the regime was backward and reactionary, and so utterly dominated by the Catholic Church, that any notion of “unification” with such a state repulsed Protestant workers.

And yet, despite this, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in the 1950s attempted to unify the North and South not through revolutionary, class struggle methods but through a guerrilla campaign. It was a futile effort doomed to failure that merely led to arrests and repression against the IRA. Following this debacle the IRA went through a period of internal discussion and re-evaluation, shifting sharply to the left.

As Hadden notes, the IRA were reduced to being largely an irrelevance throughout the subsequent period, and their role in the revolutionary events of 1968-69 was marginal at best. Much more important was the role of the workers’ movement, a fact that is largely erased from history, and which Hadden aims to rectify. As he explains:

“Most history has been written either by those with establishment and anti-labour views, or by others who have been infected by the ideas which emerged to dominate the North after 1969, particularly the ideas of republicanism. These people seek to shape the past into their view of the present. Events which do not fit in with the general sectarian colouration of “history”, and examples of working class unity in action in particular, are generally ignored since they tend to refute their ideas and pre-conceptions.” (ibid. p168)

Leaving aside Hadden’s remarks about Republicanism, which we will touch on later, recovering the history of working class unity is to be applauded. But it should be stated that it is possible to make mistakes of the opposite character. It is also possible to downplay the role of and the revolutionary elements contained within the tradition of Republicanism and to exaggerate the role of organised labour, elevating every strike and glimmer of opposition in the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) for the purpose of shoehorning history into the opposite pre-conception.

Howard Zinn’s “Peoples History of America”, is a particularly stark example of this. In this book, every small revolt, strike or act of defiance is placed on the same level as the great revolutionary events of American history.

Republicanism

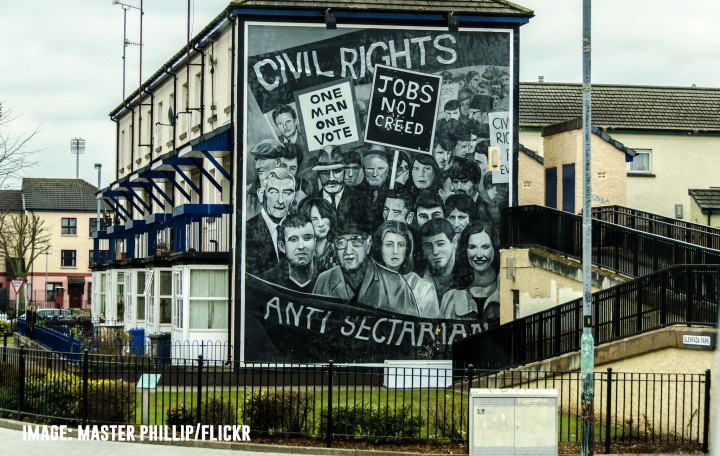

Hadden doesn’t go this far. He does a good job of bringing to light the history of working-class struggle in Ireland in the 1940s and again in the 1960s, as part of the worldwide radicalisation of workers and youth that preceded the explosive events of 1968-69, of which the movement for Civil Rights in the North of Ireland was part.

Hadden doesn’t go this far. He does a good job of bringing to light the history of working-class struggle in Ireland in the 1940s and again in the 1960s, as part of the worldwide radicalisation of workers and youth that preceded the explosive events of 1968-69, of which the movement for Civil Rights in the North of Ireland was part.

But whilst Hadden gives space to describe strikes of 3,000 workers to just 60 workers, the role of Republicanism is downplayed and distorted to the point of falsification. Whilst it is true that the IRA had a marginal presence, the revolt of working-class, Catholic youth against their awful conditions, was infused with left-wing Republican ideas, and was intimately tied up with the struggle against the Orange state.

A striking example of Hadden’s method is his description of the parade in Belfast in April 1966 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Easter Uprising, some two years before the explosion of the Civil Rights movement. The parade took place against the background of growing trade union militancy, some electoral advances for the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP), and radicalisation around the world. Hadden describes the parade thus:

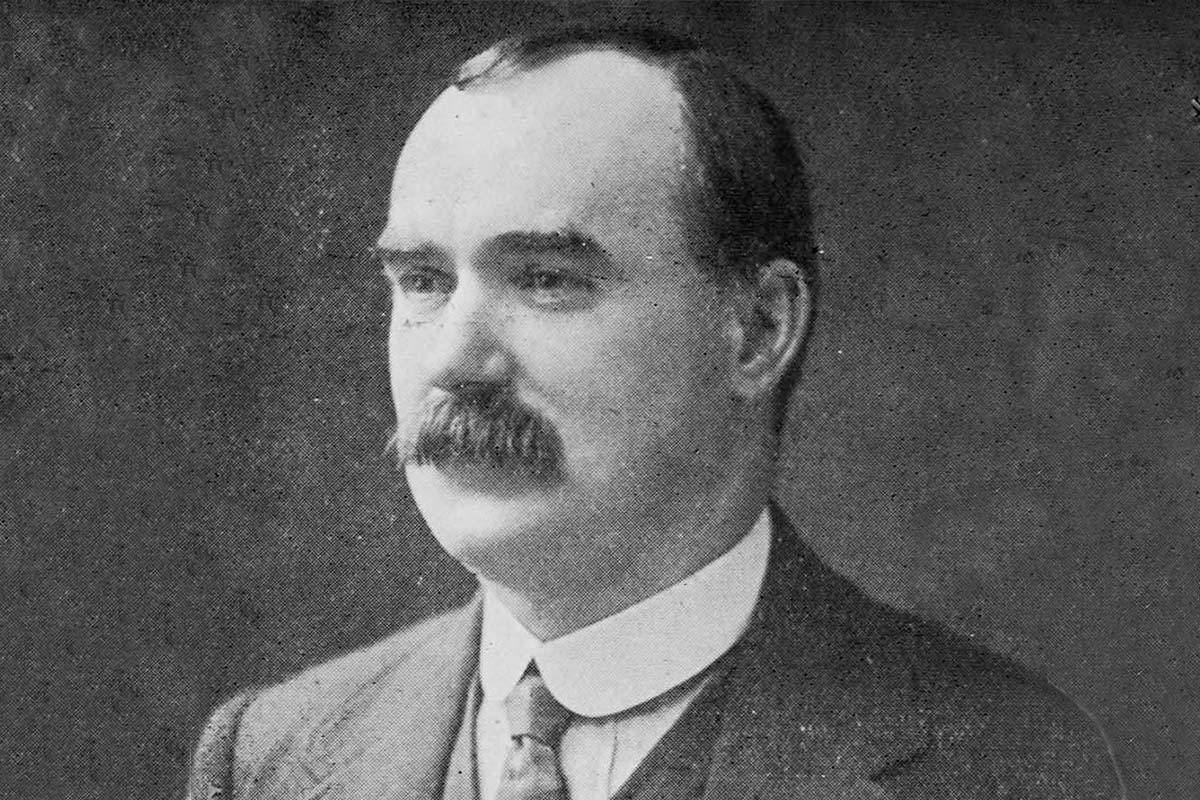

“A crowd of 10,000 turned out for the 1916 commemoration with a similar number lining the route. The size of the march did not indicate a sudden resurgence of republicanism, rather it drew support from a wide range of mainly left-wing organisations including sections of the labour movement. It coincided with a renewed interest, not in the IRA, but in the Marxist ideas of James Connolly…” (ibid. p165)

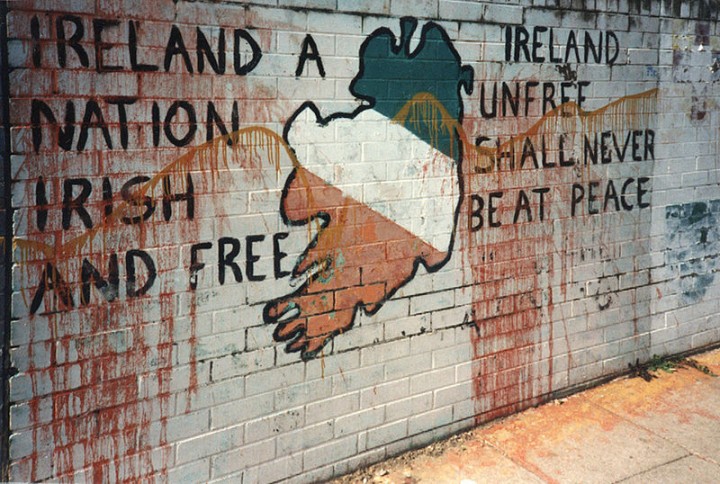

And yet eyewitnesses describe how the Falls Road that day was “festooned” with tricolour flags. At a time when it was illegal to display the tricolour in the North of Ireland, this represented an act of mass defiance! Hadden claims there was a resurgence of interest in the ideas of Connolly but not of Republicanism. This is the height of absurdity. All his life the great Marxist, James Connolly, fought for a Republic and described himself as a socialist Republican! Unlike Hadden and the SP, Connolly saw the national struggle and the class struggle as the same struggle at root.

Here we see it is Hadden who is trying to shoehorn history according to his preconceptions. Things are posed in a way that there must either have been a resurgence in Republicanism or of socialism. Republicanism and unionism are presented as twin evils: a “green” and an “orange” nationalism that are both designed to distract the working class from the real struggle, the class struggle. Things are far from being so simple.

The “nationalism” of the revolutionary, Republican youth was and is a million miles away from loyalism. Like any nationalism, Republicanism contains class contradictions, having a bourgeois right-wing, which sought to infuse Catholic sectarianism and anti-communism into the movement. However, it has always contained another democratic, revolutionary, anti-imperialist and socialist tradition. It is no accident that all the great revolutionaries of Irish history have come from the Republican tradition from Tone to Lalor, Connolly, Larkin and Mellows.

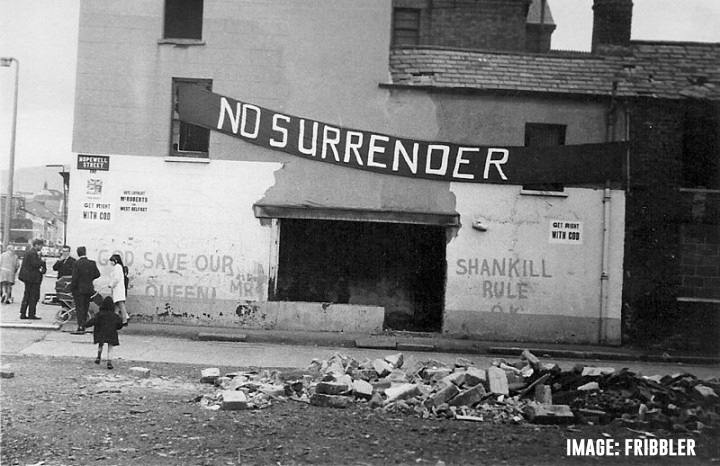

Unionism, on the contrary, is a tradition with a starkly reactionary past marked by a defence of British imperialism and Protestant supremacy, from Carson to Paisley, which was nurtured to serve the interests of British imperialism and the Protestant bourgeoisie. Unsurprisingly, every attempt to blend unionism with socialism have failed from the attempts of Connolly’s contemporary, William Walker, to create a “Labour unionism”; to the reformist unionism of the NILP in the 1970s; to more recent attempts of the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP). “Socialism” which takes as its point of departure on the national question the defence of British imperialism is a contradictio in adjecto and is doomed to wither on the vine.

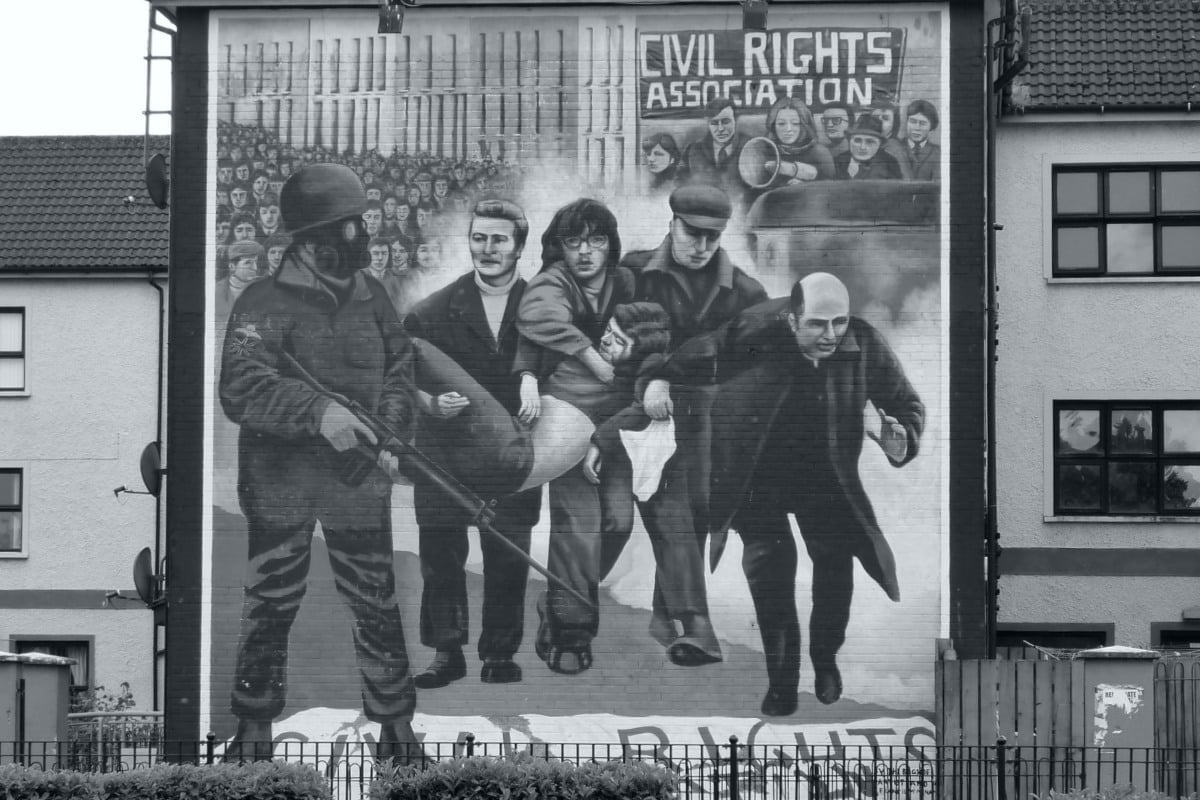

This is indeed illustrated by Hadden himself in his description of how the NILP evolved over the course of the Troubles. In 1968 there was an explosion of Civil Rights agitation against the lack of basic democratic rights for Catholics. Wherever they went, Civil Rights marchers were met by the violence of the sectarian Paisleyite thugs supported by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the B Specials.

The Civil Rights movement leadership, had it been worthy of the name, would have connected the struggle against discrimination against Catholics in questions like jobs and housing to a socialist programme for more and better jobs and housing. This could have allowed the movement to connect with Protestant workers, undercutting the sectarian propaganda of the Paisleyites who claimed the Catholics wanted to take “their” (Protestant) houses and jobs.

Instead the lefts in the Civil Rights leadership, following the Stalinist stageist theory, raised the slogan of “anti-unionist unity” – that is of cross-class unity between the revolutionary workers and youth with reactionary middle-class nationalists, jettisoning class struggle demands and methods in the process.

The NILP and trade unions failed to offer any alternative lead (although in Derry, under the influence of Marxists, the Labour Party and Young Socialists exerted a real influence in the mass movement). The result was that the Paisleyites succeeded in whipping up a pogrom atmosphere in 1969, leading to a mass uprising of Catholic workers and youth who barricaded off their communities in self-defence.

Like all reformist parties, the NILP adapted itself to the existing state. This meant adaptation to a state which upheld Protestant supremacy and the oppression of Catholics. When sectarian violence exploded, the NILP was doomed to collapse. Next to the hardcore unionist parties, its “unionism-lite” could appeal to neither Protestant nor Catholic workers.

The behaviour of the trade union leaders was even worse. The latter had the power to organise a workers’ militia to fight off the sectarian mobs, as Hadden explains. Instead they met with Northern Ireland Prime Minister, Chichester Clarke, in 1969, and the latter bribed them with £10,000 of what Hadden rightly calls “blood money” and shortly thereafter they issued a joint declaration calling for the restoration of “order” and the removal of barricades! In Hadden’s words, “‘Betrayal’ is not a word to be used lightly, but no milder term is adequate to describe NIC-ICTU’s [the trade union congress’] complicity with the government at this time.”

The question of armed self-defence was posed point blank. As Hadden notes, there were important incidents that indicated the mood of Catholic and Protestant workers, such as a mass meeting of thousands of mostly Protestant workers at the Harland and Wolff shipyard which unanimously passed a motion calling for the cessation of sectarian violence. Hadden rightly highlights these important episodes. But he fails to mention how a year later in 1970, following “The Battle of St Matthew’s Church” (a gun battle between the Provos and loyalists in Belfast’s majority-Catholic Short Strand) more backward workers at Harland and Wolff responded by expelling 500 Catholic workers from the same shipyard.

Both sides of this story have to be brought out. There was potential to cut across the sectarian divide. If the Civil Rights leaders had raised class demands to appeal to Protestant workers, and if the trade unions had organised self-defence, the Provisional IRA would not have found a vacuum to fill. The point is they did not.

The struggle descended into a struggle between the Provos and the British state; a “duel in the dark” as Hadden calls it. The methods of the Provisional IRA were insane, replicating on a far vaster scale the same failed tactics of Operation Harvest in the 1950s. The inevitable result was a descent into tit-for-tat sectarian violence. Hadden goes further than this however, claiming that the IRA’s campaign was sectarian in intent. For the majority of IRA members this was undoubtedly not the case. Large layers of working-class, Catholic youth who joined the IRA took seriously the Provisionals’ commitment to a “32-county Socialist Republic” and saw the defeat of the British Army as a step in that direction.

In the course of the violence, as Hadden notes, many of the best left-wing youth who had been members of Derry Labour Party joined the Official IRA to defend themselves. The rank and file of that organisation turned sharply to the left as a result. Marxists, rather than dismissing the struggle of the Republican youth as “sectarian” ought to distinguish between what was revolutionary in their Republicanism from the false methods of both the Provo and Officials leaderships. Instead, Republicanism and unionism are placed on an equal footing by Hadden. Both are opposed with the abstract slogan of “workers’ unity”, bearing little relation to an unpalatable reality.

Persisting in a mistake

A small mistake for a Marxist is nothing to fear. Anyone can be guilty of a shade of over-emphasis here or of under-emphasis there. A somewhat abstract formulation is not the end of the world if it is openly understood as a mistake and corrected in time.

A small mistake for a Marxist is nothing to fear. Anyone can be guilty of a shade of over-emphasis here or of under-emphasis there. A somewhat abstract formulation is not the end of the world if it is openly understood as a mistake and corrected in time.

It is when a mistake is persisted in and drawn to its logical conclusion that we come unstuck. Where this leads, Ciaran Mulholland shows us in the book’s introduction. Here Mulholland doesn’t mince words in laying out the SP’s contemporary position. After summarising Hadden’s book, we are treated to a whistle-stop tour of the current situation in Ireland, beginning with a correct point:

“The IRA campaign in fact only accentuated sectarianism and vastly reduced any prospect of its stated aim of ‘British withdrawal’. It hardened attitudes amongst Protestants in general, and in the Protestant working class in particular.”

When moving on to the present day, Mulholland redefines “coercion” to include… holding a border poll! Leaving aside the fact that Catholics have been coerced into a sectarian state for nearly a century, the worst that Republicans who raise the question of a border poll can be accused of is having illusions in British imperialism delivering such a poll in the first place and imagining that they and the sectarian hydra of loyalism would accept its outcome.

Further on Mulholland lays the SP’s cards completely on the table. Not only would a border poll be coercive, but the very idea of a united Ireland itself is in opposition to socialism!

“[…] the idea that a united Ireland is a real possibility in the years ahead is now seriously posed in the minds of many Catholics. Sections of young working-class Catholics already see this as the only way out of the grim situation they face, and will continue to do so unless a class alternative is concretely posed.” [Our emphasis] (ibid. p41)

What is a class alternative? Mulholland explains that “each community has national aspirations which cannot be ignored”. As the Protestants are opposed to a united Ireland and socialism precludes coercion, Mulholland arrives at the following conclusion:

“Put plainly, this would mean the right of Protestants, for as long as they wished, to opt either for maximum control over their own affairs or even for a separate socialist state. If such arrangements are not enough and the demand is made, we would support a separate socialist state for Protestants. Thus, the possibility of two socialist states in Ireland must be put forward as a democratic option. […] The resulting rearrangement of boundaries might be cumbersome but, on the basis of socialist change, it would be possible and could be arrived at peacefully and democratically.” (ibid. p45)

Thus the SP arrive at the hair-raising conclusion that we, as Marxists, ought to support the notion of repartitioning Ireland into Protestant and Catholic “socialist” states! This, we are assured, can be done “peacefully and democratically” under socialism. Far from solving the problem of “coercion” it only pushes it down to the local level, to the Catholic and Protestant enclaves across the North. We would be interested to know how the SP imagine such a repartitioning will be achieved in a city like Belfast, for instance, without resorting to the method of ethnic cleansing!

The SP comes to this conclusion by way of the idea that Protestants and Catholics represent separate nationalities. This is not a new idea. The Maoists raised the same idea in the past, and Militant (Hadden included!) argued against it. The attachment of Protestant workers to the union with Britain was never based on attachment to a separate national identity. Rather it had a material basis: repulsion at the idea of uniting with the South of Ireland and becoming a persecuted minority in such a state.

Opportunism

The question is: why have the SP ended up taking such a reactionary position and abandoning the Marxist position on the national question? Mulholland begins with an indubitable fact. The sectarian divide widened during the Troubles. Layers of Protestant workers were pushed into the arms of loyalism and the British state.

The question is: why have the SP ended up taking such a reactionary position and abandoning the Marxist position on the national question? Mulholland begins with an indubitable fact. The sectarian divide widened during the Troubles. Layers of Protestant workers were pushed into the arms of loyalism and the British state.

The question he then raises is: how do we reach these layers? His answer: “Two separate socialist states are thus not the most likely outcome of the transition to socialism, but we must allow this possibility precisely to convince wide layers of the democratic intentions of socialists as we struggle for the transformation of society.”

In other words, the SP raises the idea of repartition not because they believe it is likely (or even possible!) but in order to appeal to the most backward layers in an attempt to bridge the gap between Catholic and Protestant workers. Put simply put, this shows a misunderstanding of how consciousness itself develops.

Firstly, it is worth noting, loyalist workers are not interested in a separate statelet in the North, but of continuing the connection with Britain. Arguing for two socialist republics in Ireland is no more likely to attract Protestant workers than arguing for one. Secondly, whilst there is a deep feeling of anger in loyalist, working-class communities – and even of disgust at the British state and “their” politicians – a small, revolutionary organisation cannot hope to immediately reach and influence these layers in any significant way.

A small organisation, if it is to reach the most oppressed, backward and downtrodden layers of our class must first turn towards the most revolutionary elements of workers and youth – both Catholic and Protestant – and form the core of a Marxist tendency here. These young people will come to Marxist ideas through the ideas of Marx, Engels, Connolly and Larkin and will readily understand the Marxist position on the national question if it is explained clearly. The advanced Protestant youth – who are already turning their backs on the unionist parties en masse – will naturally be drawn to such a tendency.

Once the mass of workers move, the more backward layers will be drawn behind this advanced layer. The SP, on the contrary, tries to leapfrog these stages of developing a revolutionary party and connect directly with the most backward layers of loyalist workers. Bending our position opportunistically to reach these layers is worse than futile. A loyalist worker will hardly be won over by dropping the word “United” from the slogan “For a Socialist United Ireland”. Meanwhile, we will have placed barriers between ourselves, the Marxists, and the advanced workers and youth we wish to reach.

Only through struggle, on class issues, can mistrust and animosity be broken down between Catholic and Protestant workers in general. The notion that the socialist revolution can be achieved in Ireland (be it as one, two or more socialist states!) without first uniting the working class in struggle is absurd. It will be this same united struggle under a clear, socialist banner that will dissolve the opposition of Protestant workers to a Socialist United Ireland.

In the words of James Connolly, “In their movement the North and the South will again clasp hands, again will it be demonstrated, as in ’98, that the pressure of a common exploitation can make enthusiastic rebels out of a Protestant working class, earnest champions of civil and religious liberty out of Catholics, and out of both a united Social democracy.”