Lenin wrote Imperialism in the first half of 1916, while in exile in Switzerland. The historical and political context is important to understanding the significance of the work. World War I was a momentous event, which plunged the international labour movement into crisis, as the workers’ leaders failed to analyse it correctly and to politically arm the working class to fight the brutal imperialist war.

Many of the leaders of the Second International, who had capitulated to social chauvinism, portrayed imperialism as simply a “bad” policy implemented by one or another country’s capitalist government, or a consequence of nationalistic attitudes. In Imperialism Lenin cut through this confusion and politically rearmed the most advanced workers with a materialist analysis of how predatory wars, annexationism, etc. flowed directly from capitalism in its monopoly stage.

He outlined the processes through which the “old” capitalism, characterised by free market competition, has been replaced by imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism. Imperialism is characterised by the domination of monopolies and finance capital on an international scale, with the export of capital leading to the big imperialist powers carving up the world.

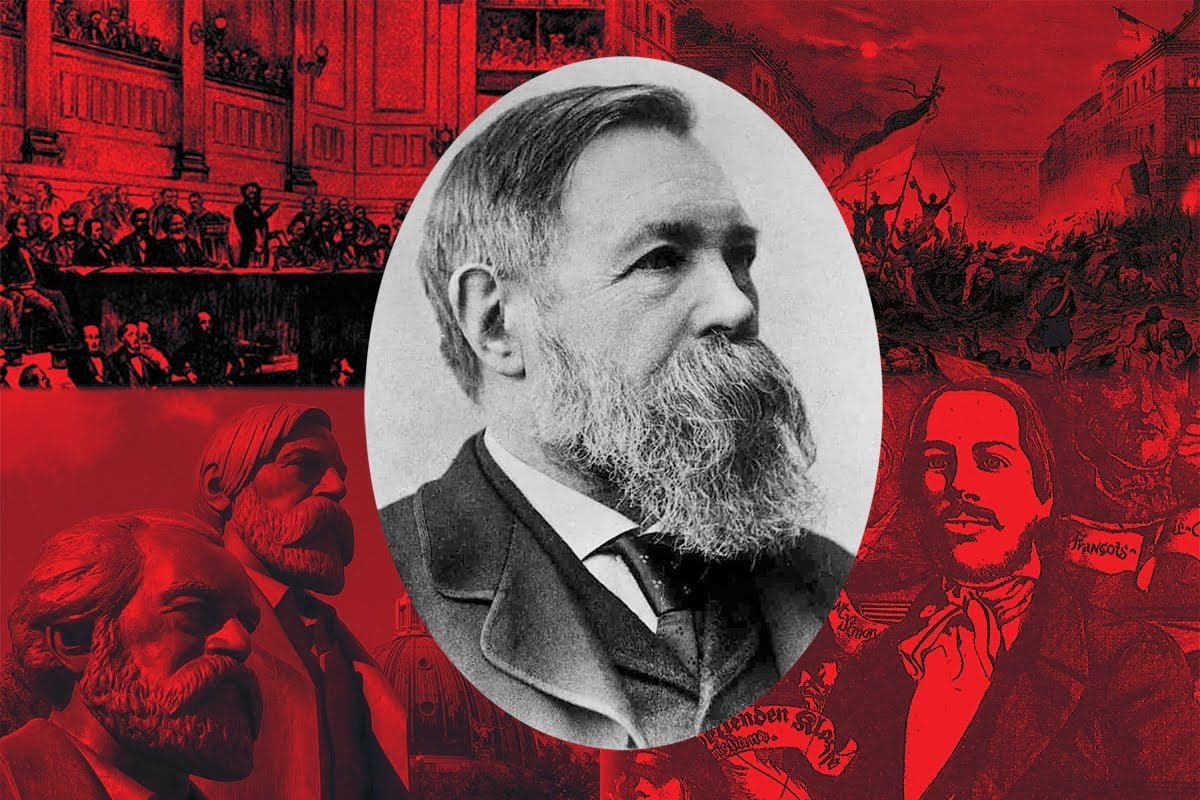

That competition would eventually give way to monopolistic domination was something that Marx and Engels had predicted in advance. The fact that Marx and Engels’ predictions were borne out by history is a testament to the strength of the dialectical materialist method and to the continuity of theory stretching from the founders of scientific socialism to Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Throughout the book, as he outlines his analysis of imperialism, Lenin also attacks petit-bourgeois reformists and social chauvinists like Kautsky for their failure to provide a Marxist explanation of imperialism, and consequently their failure to take an independent working class position on the eve of WWI, which was the ultimate betrayal that killed the Second International.

Imperialism remains a vital theoretical tool for Marxists to cut across confusion on this question within the labour movement. All around the world the correctness of Lenin’s argument is proven as the balance of forces between imperialist powers – declining American imperialism and rising Chinese imperialism in particular – is laying the basis for new struggles for markets and spheres of influence, reflected in growing tensions, trade wars, proxy wars, etc.

Chapter 1: Concentration of production and monopolies

In Chapter 1, Lenin illustrates how capitalism tremendously concentrates production in the advanced capitalist nations with diverse examples. His conclusion is that free competition leads to the victory of the bigger, more productive enterprises and eventually a tiny handful of monopolies must come to dominate the entire economy. This is the most important feature of the modern capitalist economy according to Lenin and is a confirmation of a tendency described already by Karl Marx but denied by the apologists of capitalism.

Lenin explains that monopolies were barely discernible before the 1870s but then developed over a long period, becoming permanent fixtures in all the developed capitalist nations after the crisis of 1900-03. These monopolies thrived by massively improving technique but also by charging monopoly prices.

Lenin described the grand scope of these behemoths. Instead of manufacturers producing for an unknown market, these monopolies estimate the resources of entire nations, they calculate the skills of the entire labour market, and base their calculations on the capacities of entire national markets to absorb their products, which they come to an agreement on dividing between themselves.

What is the meaning of this? Production is becoming increasingly socialised. Despite singing the praises of “competition”, the capitalists are – against their will – substituting it with economic planning! And any dream of going back to free competition is a reactionary utopia.

Study questions:

- Why does the doing away with competition not lead to the doing away of crises?

- Why is the idea of “breaking up” monopolies a reactionary and utopian one?

- By what specific mechanisms do monopolies assert their domination?

Chapter 2: Banks and their new role

Concentration into monopolies also occurs in banking. This, Lenin explains in Chapter 2, occurs by the same mechanism as in industry but also through massive holding companies, which allow the big banks to dominate smaller banks. Banks used to be just middlemen for credit. But as they formed monopolies, they concentrated almost all of the money wealth of society into their own hands, as well as knowledge of the business practices of all their depositors. They became extremely powerful entities, with life and death control over the credit lines to all of industry.

Lenin describes a trend at the end of the 19th century for the banks to employ directors and departments that specialise in various industries and an increasing “linking up” with industry (through reps on boards, etc.). We see the genesis of giant financial monopolies as the banks themselves intervene in and begin to dominate industrial capital.

Lenin explains that we have in the modern banking monopoly the form of “universal book-keeping”. However there is a contradiction. Production is becoming socialised, but the means of production remain in private hands. This leads to all kinds of imbalances. While the banks almost “plan” production, they don’t completely do away with competition. From free competition we have now a mix of competition and monopoly. Lenin makes the pointed remark that this new stage of capitalism shows a society in transition – but ‘into what is it “developing”?’, he asks.

Study questions:

- Why do banks cease to be mere middlemen for credit once monopolies are established?

- How do giant banking monopolies dominate smaller banks?

Chapter 3: Finance capital and the financial oligarchy

With the rise of these giant monopolies, industrial and banking capital tend to coalesce into the giants of finance capital. In this chapter Lenin describes the system of holding companies as the universal “cornerstone” of this system.

With a 50% share in a company, one large capital can dominate many smaller capitals. In reality, the percentage needed is far smaller because the small shareholders are inevitably divided. This is the answer to those who want to “democratise” the economy by making every worker a shareholder (as some reformists argue). Lenin points out that this only increases the domination of finance capital.

The financial oligarchy thus formed makes huge profits from lending, swindling and speculation. Commenting on this domination Lenin describes how, “capitalism, which began its development with petty usury capital, ends its development with gigantic usury capital.” To illustrate his point he uses the example of France. France in 1916 had a stagnant industry and population growth had stalled. And yet a handful of millionaires were growing fat, precisely through usury.

Lenin also describes the other ways that this financial oligarchy extends its domination into every sphere of public life. Ruined businesses are snapped up after every recession, only to be reorganised or to have their assets stripped. By buying up infrastructure and transport, finance capital finds new avenues for speculation on a huge scale in the property sector. Even the state is not immune, as – directly or indirectly – public officials are also bought up.

Ending the chapter, we see how a handful of advanced economies have become dominated by monopoly capital. They in turn have a monopoly over the whole world. In Lenin’s day just four nations – Britain, France, Germany and the USA – accounted for 80% of all securities issued. In the following chapter, Lenin develops the question of the massive export of loan capital.

Study questions

- Can you think of a modern example of reformist politicians arguing for “democratising” the economy by making workers shareholders? How did that end up?

- What similarities are there between Britain today and France in the early 20th century?

- By what means does finance capital dominate all spheres of public life today?

Chapter 4: Export of capital

The modern epoch has another characteristic. In the age of “free competition”, capitalists tended to export goods. In the age of imperialism, there is added to this the massive export of capital itself. As a handful of advanced capitalist countries have come to be dominated by monopolies, these countries have developed a massive excess of capital. This capital has only one place to go: it is exported.

Lenin notes that this doesn’t mean that there aren’t massive areas that are underdeveloped in the “advanced” economies. The masses still lived in poverty and agriculture was in a state of backwardness. But development under capitalism always has a “combined and uneven” character and capital is never used simply to lift people out of poverty.

The point is that in a few countries capitalism is unable to find profitable areas for investment. In other words, it has become overripe for overthrow in these countries. Instead, capital is exported to backward countries where profits are high due to cheap land, resources and labour. The advanced capitalist nations therefore begin to live parasitically off the massive exploitation of the backward countries.

Where does this exported capital go to? For Britain, Lenin explained how it is mainly in investments in its colonial possessions. In the case of France, mostly as loans within Europe and particularly Russia. Germany, lacking colonies, mostly exported capital to Europe and America.

The export of capital may slow down the development of the advanced nations but it actually furthers the development of capitalism in the countries to which it is exported. However it does so in a combined and uneven manner. Huge, modern factories spring up next to subsistence farmers, feudal estates and other pre-capitalist modes of production.

Thus, finance capital spreads its net over the entire world. Colonial banks are established as subsidiaries of the big finance houses everywhere and they come to dominate trade. This figurative division of the world among the finance capitalists leads to the actual division of the world, as Lenin goes on to explain in the next chapter.

Study questions

- Can you think of examples of combined and uneven development in the “advanced” economies today?

- How do the effects of the export of capital affect the revolutionary tasks of workers in so-called “underdeveloped” countries?

Chapter 5: Division of the world among capitalist associations

In this chapter, Lenin begins by outlining how a handful of dominant monopolies in different nations can join together, forming worldwide cartels, or “super-monopolies”. Under capitalism, domestic markets are inextricably bound up with the international market. Thus, monopolies that first dominate their own home market then go on to establish international cartels with their foreign counterparts. They agree on how to carve up the global market, refrain from competing with each other within individual countries, and share research and technology.

He then goes on to dispel the notion, propagated by bourgeois writers and absorbed by Kautsky, that this international trustification would lead to unity and peace. Lenin explains that the balance of power struck by a cartel can be revised at any point, based on the changing balance of forces, the combined and uneven development of capitalism, and particularly in situations of crisis and/or war.

He sheds light on the opportunistic character of the reformists and social chauvinists who focus on this or that form of the struggle among capitalist monopolies to carve up the world, i.e. whether they do so peacefully one day or by military means the next.

He explains that this question is always secondary to the nature of this struggle and to its class content. It is in the interest of the bourgeois to obscure this nature. For the workers’ leaders to obscure its nature is a betrayal.

Lenin has already explained that imperialism is not a feature or attitude of capitalism: it is the highest state of capitalism itself, an inevitable outcome of free competition. The economic structure of the highly concentrated global imperialist system is what compels the capitalist class to divide the world among themselves.

Lenin ends the chapter by explaining how relations between international cartels grow up on the basis of the economic division of the world and that parallel and in connection with this political alliances between states grow up based on the territorial division of the world.

Study questions:

- Can you think of a modern example of reformists opportunistically obscuring the real character of imperialism?

- Can you give a modern example of struggles between international cartels and monopolies to redivide the world market? What change (in the balance of competing strengths, extraneous factors, etc.) precipitated the change from peaceful coexistence to a struggle for redivision?

Chapter 6: Division of the world among the great powers

Lenin begins this chapter by illustrating how the period 1876-1900 was characterised by the final partition of the world. The colonial policy of the imperialist powers had completed the seizure of all unoccupied territories on the planet. This partition was “final” in the sense that there were no new territories for the imperialist powers to compete. This didn’t mean that this division was static or permanent but that new territories could only be acquired by redivision.

Colonialism in the epoch of imperialism is qualitatively different from the colonialism of free trade because it is inextricably linked to financial monopolies. Colonial policy in the age of imperialism has the aim of giving monopolies a guarantee against their competitors, by monopolising control of all the sources of raw material and labour in a specific territory.

However, there were massive imbalances in the division of the world. In the late 19th Century countries like Britain and France took the lion’s share of colonial possessions. Germany in particular arrived late on the scene. But now the old capitalist powers, Britain and France, were stagnating whilst newer powers like Germany, the US and Japan were growing very rapidly. Finally you also had a country like Russia, where imperialism existed in the same economic system as pre-capitalist property relations, in an excellent example of combined and uneven development.

Lenin explains that there is a contradiction here: the countries with the fastest pace of economic and technological development are not necessarily the ones with the most colonies. This contradiction can only be solved through war for redivision between these powers.

Study questions:

- What is the difference between a colony and a semi-colony, in Lenin’s description? Can you think of a modern country that could be considered a semi-colony?

- In this chapter the notorious imperialist and diamond magnate, Cecil Rhodes, says, “If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.” What does he mean by this? Why does Lenin describe Rhodes as a “somewhat more honest social-chauvinist”?

- Can you think of other examples where a changing balance of forces has posed the question of a redivision of colonies or “spheres of influence”?

Chapter 7: Imperialism as a special stage of capitalism

In this chapter, Lenin once again polemicises against Kautsky and his conception of imperialism. Lenin summarises his own analysis, by tying together the threads of what he has discussed so far. He outlines the basic features of imperialism: the concentration of production and capital, leading to the formation of monopolies; the merging of bank capital and industrial capital; the export of capital, which acquires a distinct character from the export of commodities; and the formation of international monopolies.

By emphasising that the features of imperialism are essentially products of the development of capitalism itself, Lenin contrasts his analysis with that of Kautsky. For Kautsky, imperialism was not a stage of capitalist development but rather a policy pursued by the capitalists.

Kautsky was trying to separate the political dimension of imperialism (wars, occupations, annexations, etc.) from its fundamental economic basis. The conclusion of this type of thinking is that, since imperialism is only one type of policy in present-day capitalism, other, more peaceful ones are possible. Ultimately, this opens the door for reformist ideas because it does not rule out the possibility of a different kind of bourgeois politics on the same material basis.

Finally, Lenin proceeds to attack Kautsky’s “ultra-imperialism”, which consisted of the idea that the dominance of international cartels would lessen the unevenness and contradictions inherent in world capitalism. Lenin has already explained that the apparent truce between cartels can be subject to change and redivision; but in this chapter he goes further and shows that finance capital and trusts actually increase the unevenness in the rate of growth between different parts of the world economy. For example, in the lead-up to WWI Germany was growing at a faster rate than Britain but Britain still had more colonies. These types of contradictions, Lenin explains, will lead to wars between the imperialist powers.

Study questions:

- Can you think of contemporary reformist ideas/policies on imperialism that echo Kautsky’s thinking?

- Kautsky claims that imperialism represents a striving by industrial capitalist nations to annex agrarian territory. Lenin explains in this chapter that this is wrong. Why?

Chapter 8: Parasitism & Decay of Capitalism

Lenin explains that an important aspect of imperialism is the increasing “parasitism” of a stratum of the population in the advanced imperialist nations. The export of capital, a key feature of imperialism, takes place in part because finance capital cannot find sufficient scope for profitable investment in the limits of the imperialist nation. The export of capital meanwhile allows an entire section of the population to live at the expense of the dividends drawn from these massive investments abroad.

Lenin uses the example of Britain throughout this chapter. Despite the fact that Britain was the biggest exporting nation in the world, Lenin showed that it derived five times more income from dividends, interest etc. than profits made on foreign trade.

Furthermore, imperialism is also characterised by tendencies to stagnation and decay. This is caused by the monopolies’ stranglehold on the economy: this tendency can gain the upper hand for periods at a time and monopoly prices will eliminate the incentive to invest in technological improvement. Secondly, the conversion of the bourgeois into a class of rentiers increasingly divorces them from the process of production.

These features of imperialism that Lenin sums up have important consequences for the socialist movement. The large monopoly profits of a few very rich countries are used to bribe an upper layer of the working class, thereby strengthening opportunist tendencies in the labour movement as this upper stratum is divorced from the mass of the working class and its needs.

Study questions:

- Considering capitalism today, where do we see confirmation of:

- its parasitism, and

- the fact that it is a system in decay?

- Why do the above mentioned features of capitalism in its imperialist phase mean that:

- Opportunism cannot completely triumph in the workers’ movement as it did in Britain in the late-19th Century?

- Opportunism completely merges with bourgeois policy to become “social chauvinism”?

Chapter 9: Critique of Imperialism

In this chapter, Lenin sums up the attitudes of different classes towards imperialism. The propertied classes, he says, have gone over completely to the side of imperialism and the most bourgeois commentators can do is to cloak their defence of imperialism in meagre calls to reform it in order to curb its most violent aspects.

Due to the pressures on small businesses created by the domination of the financial oligarchy and the relative elimination of competition, there developed a petit-bourgeois democratic opposition to imperialism in many advanced countries at the beginning of the twentieth century. This position contrasts “freedom”, “democracy”, “competition” as alternatives to the existing features of the imperialist epoch: this type of idealist thinking once again sees imperialism as a policy rather than a stage in the development of capitalism.

Lenin explains that it is not the task of the workers’ movement to oppose imperialism by defending a hypothetical return to a bygone era of competition and free trade. This would be impossible in any case, as monopolies themselves arise from growth and concentration of production and capital in the era of free competition. Marxists should be clear that the only alternative to imperialism is socialism. We don’t want a return to free competition, we want to end competition by putting an end to capitalism.

Study questions:

- Can you give an example of modern bourgeois commentators trying to cloak their defence of imperialism?

- Can you give examples of modern petit-bourgeois critics of imperialism?

- In what way could Kautsky’s critique of imperialism be regarded as reactionary?

Chapter 10: The Place of Imperialism in History

Lenin ultimately characterises imperialism as monopoly capitalism, a transitional phase characterised by monopolies and cartels; by the new role of the banks as a the monopolists of finance capital; and by a new colonial policy centred around the struggle for raw materials and capital exports.

Imperialism has led to increases in the cost of living for the working masses provoked by the domination of the cartels. This is, according to Lenin, one of the main features of imperialism as a transitional era, one that begins with the consolidation of finance capital. The main features of this transitional epoch are the increased concentration and socialisation of production.

On the international scale, imperialism has increased the unevenness of states’ economic development because it has built a system where a few imperialist, rentier states dominate and exploit a large number of weaker states. For Lenin, the oligarchical powers of the monopolies are a symptom of a “moribund” capitalism, a system in transition.

Study questions:

- Why is imperialism a transitional phase?

- How does imperialism pave the way for socialism?