The toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol on 11 June has brought to attention Britain’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. Although officially abolished in Britain in 1807, this horrific trade in human beings was central to the rise of capitalism and the rise of Britain as a world power in particular.

Slavery has existed throughout the history of class society in various places. But it is understood most commonly today as the barbaric episode in which humans were brought from West Africa and transported to plantations in America and the Carribean.

In the early 15th century, Portugal ‘explored’ the coast of Africa, primarily in search of gold. It was the first European country to do so. And the Portuguese quickly enjoyed the prospect of trade with Africa without having to go through the block of the Islamic countries in the north. At this stage, although trade in slaves did take place, it was in small numbers. Gold was the real prize.

In the 1470s, for example, the Portuguese reached what became known as the ‘Gold Coast’ – Ghana. In the next period, we see the beginnings of African gold being traded into Europe. At this stage, Britain could only look upon Portugal in envy. Eventually though, the trade in human beings became the more profitable enterprise.

Architect of slavery

In time, Britain caught up. British involvement in the trade began around the middle of the sixteenth century. Britain soon became a key architect of the transatlantic slave trade. Through this, it acquired the high profit levels necessary to become a mighty capitalist power.

Companies that participated in the slave trade were an important part of the industrial revolution. For the rising capitalist class, the slave trade played a pivotal role in the expansion of the global market. In the words of Karl Marx:

“It is slavery which has given value to the colonies, it is the colonies which have created world trade, and world trade is the necessary condition for large-scale machine industry. Consequently, prior to the slave trade, the colonies sent very few products to the Old World, and did not noticeably change the face of the world.”

Portugal and Britain were the two most ‘successful’ slave-trading countries, accounting for about 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas. Although there were ports in Liverpool, Bristol, Portsmouth and Lancaster, much of Britain did not see first-hand the nature of slavery.

Britain’s wealth came from trade, rather than an internal economy dependent on the labour of slaves, as was the case in America. The ideological defence of slavery and racism was therefore intensified in the American states – in part due to the physical presence of the plantations.

Britain’s domination peaked between 1640 and 1807, when the British slave trade was technically ‘abolished’. In the United States, however, slavery continued right upto and throughout the civil war, only ending in 1865.

Economic motivation

The British ruling class has a misguided sense of superiority on the matter of abolition. It was indeed the first to do so (although in reality it continued up until the 1830s).

However, this was not on account of some sudden change of heart regarding the enslavement of black people. Rather, it was motivated purely by economic interest, as the dawn of capitalist society meant that slavery was less profitable than ‘free’ wage labour.

A.L. Morton notes in his work, A People’s History of England: “Profitable as the slave trade proved during the 18th century, its suppression in the 19th century was even more profitable.” Slavery, in short, simply became uneconomical.

It is true that there was huge pressure brought on the British state by the abolitionist movement, both at home and in the colonies – a movement which included many radicals.

On top of this were growing slave uprisings. The great slave revolt of 1831 in Jamaica (one of many others across the islands) was a turning point for the already heavily outnumbered white settler population.

Marx recognised that, for the ruling class, there were limits to which slavery and modern machinery could be compatible. The slave might be very cheap, but ultimately they have no incentive to look after machinery or increase productivity. At the end of the day they remain a slave. A wage earner, meanwhile, must satisfy their boss’ expectation to have work the following day.

Marx also noted the importance of slave revolts:

“In my view, the most momentous thing happening in the world today is, on the one hand, the movement among the slaves in America, started by the death of Brown, and the movement among the slaves in Russia, on the other…I have just seen in the Tribune that there was a new slave uprising in Missouri, naturally suppressed. But the signal has now been given.”

Sham abolition

In fact, the abolition of the slave trade – although inconvenient for those in the business – saw the slave owners compensated very handsomely. The modern equivalent of £17 billion was paid in compensation to slave owners.

This is something one might have expected the ruling class to shy away from. But no, the Treasury tweeted proudly about this fact in 2018: “Millions of you helped end the slave trade through your taxes.”

This is a message to black British people saying, “although some of your ancestors were enslaved, they were eventually made ‘free’; and now you get to pay the families of those who owned them!”

Abolition was a sham in itself. Compensation was not enough, so the government implemented an ‘apprenticeship’ scheme in which slaves had to continue laboring for their former masters for a period of four-to-six years in exchange for provisions: 45 hours a week for no pay.

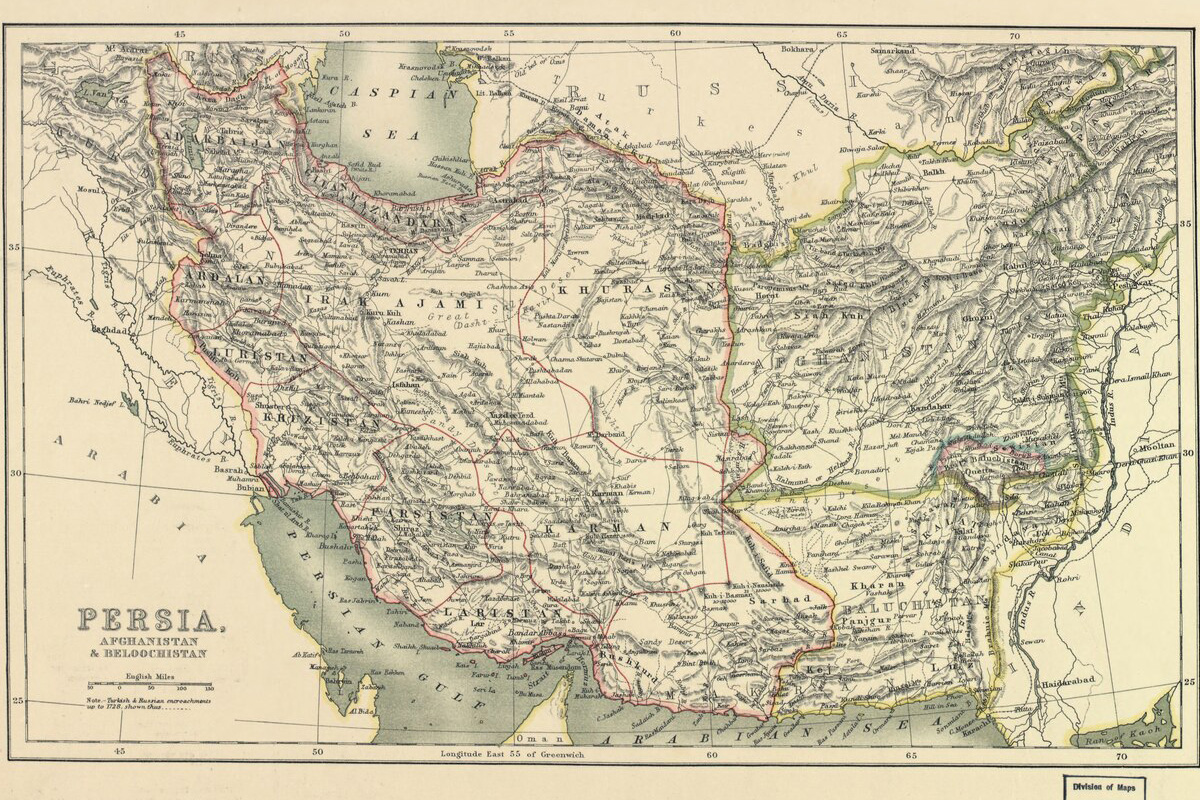

The Abolition Act itself paved the way for British forces to become ‘international policemen’ on slavery. British naval squadrons were set up to patrol the coast of West Africa and the Caribbean looking out for illegal slavers. In reality, this was the beginning of a new exploitation and conquering of Africa, to be redrawn in the interests of British capitalism.

Remember the past

The legacy of slavery lives on in our brutally unequal society today. It was abolished, but exploitation remains. And the exploitation of black people is therefore woven into this system today.

We see that in our statues. We see that in the fact that the compensation of slave owners was paid by the British taxpayer up until 2015, well over 200 years later. We see it in intergenerational poverty; housing segregation; and in cultural attitudes that perceive black people as ‘dangerous’, ‘violent’ and unintelligent.

That legacy is also in the faces of those who rule over us today. Former prime minister, David Cameron, has familial roots in this wealth. Gen. Sir James Duff, an army officer and MP for Banffshire in Scotland during the late 1700s, was the son of one of Cameron’s great-grand uncles and was awarded £4,101 – equivalent to more than £3 million today – to compensate him for the 202 slaves he owned.

But it is not just Cameron. You can take your pick of the peers who sit in the House of Lords – and the Queen herself – many of whom are direct descendants from these mighty slave-owning families.

The wealth of Britain’s capitalist class was borne from the enslavement of black people. Marx was right when he said that capitalism was born with “blood dripping from every pore”.

Boris Johnson and the Tories say we must remember the past. We do: we remember the crimes of the British ruling class, from slavery to Windrush.

The working class remembers. And from this history, we have learnt the truth: that the rule of a minority over the majority is the most barbaric form of life. And we must fight to abolish it – completely.