Paramount Skydance, after months of bidding to acquire WarnerBros Discovery, found out on 5 December that the WarnerBros board had agreed to a multi-billion dollar deal to sell the company to Paramount’s rival, Netflix.

As the Financial Times detailed, the bidding war began shortly after Paramount had been taken over by David Ellison. Not to be beaten, Paramount attempted to outmaneuver Netflix by making a hostile takeover bid, where the company goes straight to the shareholders over the board, on 8 December.

Which takeover – if either – will be successful remains to be seen, as the sale and subsequent legal and regulatory battles will likely be protracted. Nevertheless, the potential sale of a legacy studio to a streaming giant will cause an earthquake in Hollywood.

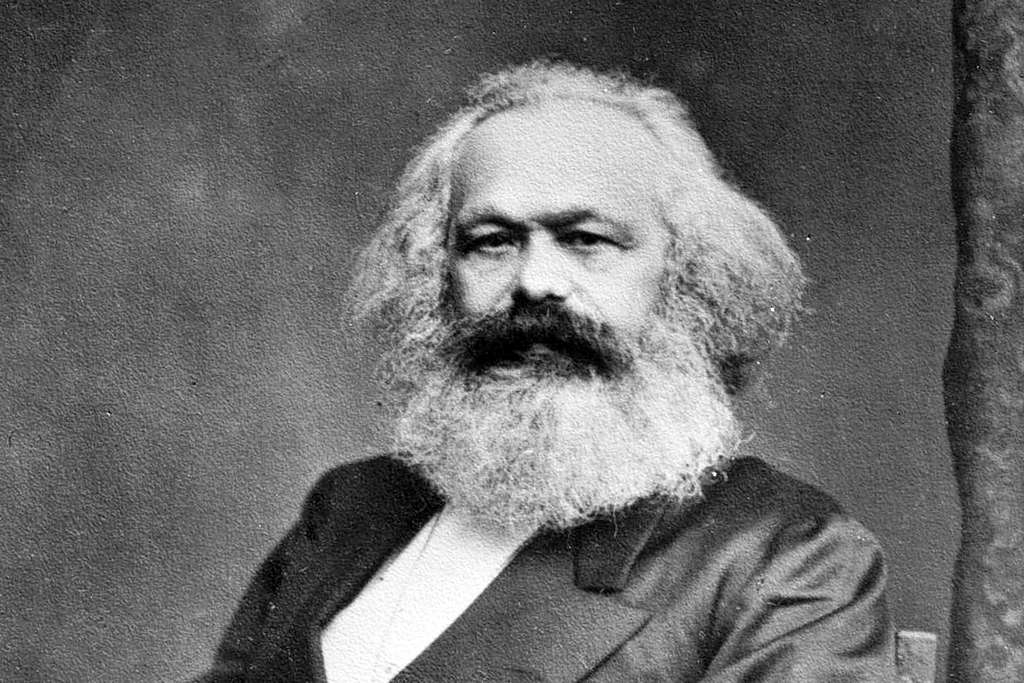

Marx was right

The titanic deal confirms Karl Marx’s predictions that enormous amounts of capital would concentrate into a tiny handful of capitalists.

In its heyday, capitalism was spurred forward by competition. The only way to gain a larger share of the market over your competitors was to innovate.

The law of competition applied to every industry, including film. At the beginning of the 1920s when silent films dominated, Warner Bros. were a smaller studio, but their release of the first “talkie” with The Jazz Singer in 1927 gave them a massive competitive advantage.

In every competition where there are winners, there are losers.

Companies who are unable to compete fold in the face of bigger and better companies and are swallowed up by them. The companies who are winning the competition grow by purchasing or merging with their weaker competitors, and by buying companies above and below them in the production chain.

By the end, the process of competition turns into its opposite, as only a few – now gigantic – businesses remain, and they hold an effective monopoly on the market.

In the United States, those winners are The Walt Disney Company, WarnerBrosDiscovery, Comcast Corporation, Paramount Skydance, News Corporation and Netflix. They own just about all of the news, film and television channels, studios, intellectual property rights and streaming platforms.

Communists are often accused of wanting everything to be run by the state, whereas capitalism offers freedom of choice and innovation. Yet the exact opposite is true! Six, soon to be five, mega corporations accountable to wealthy shareholders control pretty much the entire media industry!

These colossal companies are so large and produce on such a scale that they are able to accurately estimate the available natural and human resources of entire nations. They can estimate the capacity of the entire market to produce and consume goods, and then agree on how to divide this market up amongst themselves.

In effect, these giant monopolies are planning production, and are able to produce much more efficiently than the isolated small companies that preceded these monopolies could.

Whoever buys Warner Bros. will have access to tremendous financial and productive resources. In particular, the combination of Netflix’s and Warner Bros.’ production studios and the physical and streaming networks each holds would provide Netflix with the ability to produce on an extraordinarily efficient scale.

A fetter on culture

The potential benefits of this sort of merger for consumers are clear – the centralisation of different cultural products into one area would mean a single streaming service would make it easier for millions to access a wider range of television shows and films.

Currently, to watch Citizen Kane, The Sopranos, and Stranger Things, a British consumer would need subscriptions to BFI Player, Now TV, and Netflix which could cost in the region of £30 per month. A merger between Netflix and Warner Bros. could reduce this cost to £12.99 per month, making it much easier for the average person to engage with culture.

A single, enormous company would also have fewer costs than two gigantic companies because of economies of scale. For example, Netflix estimates they may save $2 – $3 billion just by merging the support and technology areas of the business.

This could also benefit consumers, as – alongside the super-profits a monopoly of this size would generate – this extra cash could subsidise less profitable (or even loss-making) artistic ventures and theatrical runs, which, although unprofitable, could go on to have an outsized impact on the development of art.

The scale of the profits being made could allow every person involved in the industry to be paid a substantial wage whether they are in work or between jobs, allowing people from less privileged backgrounds to participate freely in the production of film and television. This could result in a huge impetus for cultural development.

But under capitalism, the opposite will happen. A capitalist’s sole concern is the generation of profit. If they produce something useful, or spur the development of society onwards, that is solely incidental.

In the era of monopoly capitalism, the motivation to compete and innovate is removed. Instead, these companies only seek to retain control of their corner of the market and make super profits.

As such, the acquisition of Warner Bros. by another studio giant will not spur on the development of new culture. Instead, we can expect to see the new owner milk the cash-cow of franchises and intellectual property (IP) that are owned by Warner Bros. or their subsidiaries (such as Harry Potter, Friends, DC comics, The Lord of the Rings, and Looney Tunes) try to get as much profit from as little investment as possible.

This is exactly what happened following Disney’s acquisition of Marvel Studios and Lucasfilms, where new media using the same IP has been churned out on a regular basis to generate a steady stream of profit with minimal investment and innovation required.

In fact, the top 10 grossing films of 2024 were all either prequels or sequels!

Given this steady stream of reliable income will exist, the stagnation of culture will be exacerbated because the already over-zealous tendency of executives to cancel unprofitable shows and film productions will increase tenfold.

Ironically, some of the most lucrative television shows produced by HBO (a subsidiary of Warner Bros.) – such as Game of Thrones and The White Lotus – did not begin to gain widespread public acclaim until the end of their second season. It seems unlikely either would get given that second series if they debuted under a future merger.

The death of cinema?

The savings and super-profits generated by a massive monopoly will not be used to subsidise less-profitable films or theatrical runs. Instead, they will be paid out as dividends to shareholders.

More concerningly, a merger between Warner Bros. and Netflix in particular would represent an existential threat to cinema.

Although he has recently attempted to row his comments back, Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos sent a clear signal to shareholders and investors at the Time100 summit when he described theatrical releases as “outdated” and “out of step” with modern consumption.

From a capitalist’s perspective, there is some truth to this. These releases are full of financial risk, require costly advertising campaigns, and are ultimately less profitable than streaming. For Netflix too, why would they want to share their profits with the cinema chains when they have a one stop shop streaming platform.

New York Times Hollywood reporter Nicole Sperling summed this up this conundrum perfectly:

“You have to spend $50 million to market a movie in the US so that people will show up on opening weekend. You spend two to three years making the movie. You spend this much to market. You can know on Saturday morning if you’re dead in the water and the movie’s been deemed either a hit or a failure. It happens that quickly. It’s like gambling with ridiculous odds.”

Currently, Netflix films often have a short theatrical release of up to 17 days so that they are eligible for award nominations before they are launched on the streaming service. Sarandos has stressed that he isn’t against theatrical releases in general, rather, he believes that long, exclusive theatrical releases aren’t “consumer-friendly”.

But under capitalism, the laws of the market will prevail – with limited disposable income, it doesn’t make financial sense for the average person to spend the equivalent of their Netflix subscription to see a film in cinemas that will be available for them to stream two weeks later.

Streaming offers a fantastic way to access culture in the home, and it lowers barriers to cultural consumption, but it is akin to watching a football match on the television rather than in person: it is no substitute for the real, social way this form of culture is meant to be experienced

A handful of companies look set to dictate what culture we consume, and how we consume it, for a generation or more, and the tendency will be to serve us increasingly thinner versions of a gruel we’ve had 100 times before.

Should Communists support anti-trust legislation?

Faced with the prospect of this merger, some unions representing workers in Hollywood are pushing back. The Writers Guild of America have come out particularly strongly, stating “this merger must be blocked”.

This attitude of wanting to prevent the merger when faced with the domination of an unrestrained monopoly who have the power to push wages down, charge monopoly prices, and sabotage culture is understandable, to a degree.

But, at best, this attitude is naïve and utopian. As explained this processes of monopolisation and horizontal and vertical integration are an inevitable outcome of the development of capitalism. Even if legislation, regulatory action by the Federal Trade Commission, or push back from the unions prevented this merger, it just sets the clock back and delays what is otherwise inevitable.

At worst, this attitude is reactionary. Beyond the fact that this attitude implies that a return to an earlier form of capitalism would somehow be better, a company with the size and scale to plan production produce so efficiently that it can afford to subsidise cultural consumption and development is an objectively good thing that cannot be offered by earlier stages of capitalism.

This case shows us that capitalism has reached a dead end – it’s developed technology and society to the point where this massive leap forward for cultural development and participation is possible but, straitjacketed by laws of the market, these resources will be used to dilute and weaken culture in the name of dividends.

There is a glaring contradiction between the massively socialised method of planned production and the private appropriation of the profits of production by a few small parasites.

However, the ‘union tops’ in the United States are so bought into the current system, that they cannot see the need for socialism staring them right in the face.

Rather than trying to turn the clock back, the unions should instead be fighting to take control of these companies out of the hands of a few rich investors and executives so that instead it is owned, and run, by the crew members, writers, actors, and directors who make these films and television shows.

They, along with the genuine democratic participation of the whole society, could then democratically choose how to best use the resources. Given the stake and interest these workers have in cultural development – this would inevitably result in the protection of theatrical releases and less profitable cultural artefacts.

More importantly, it would lead to the real flourishing of art and culture, free from the straightjacket of capital.