The ‘Communards’ – the armed people of Paris, the creators and defenders of the Paris Commune — were absolute pioneers.

They picked up where the Parisian masses had left off in the Great French Revolution of 1789-93. But they took one more gigantic and decisive step, the working class achieved the seizure of state power. This had never been done before, they had no blueprint to follow.

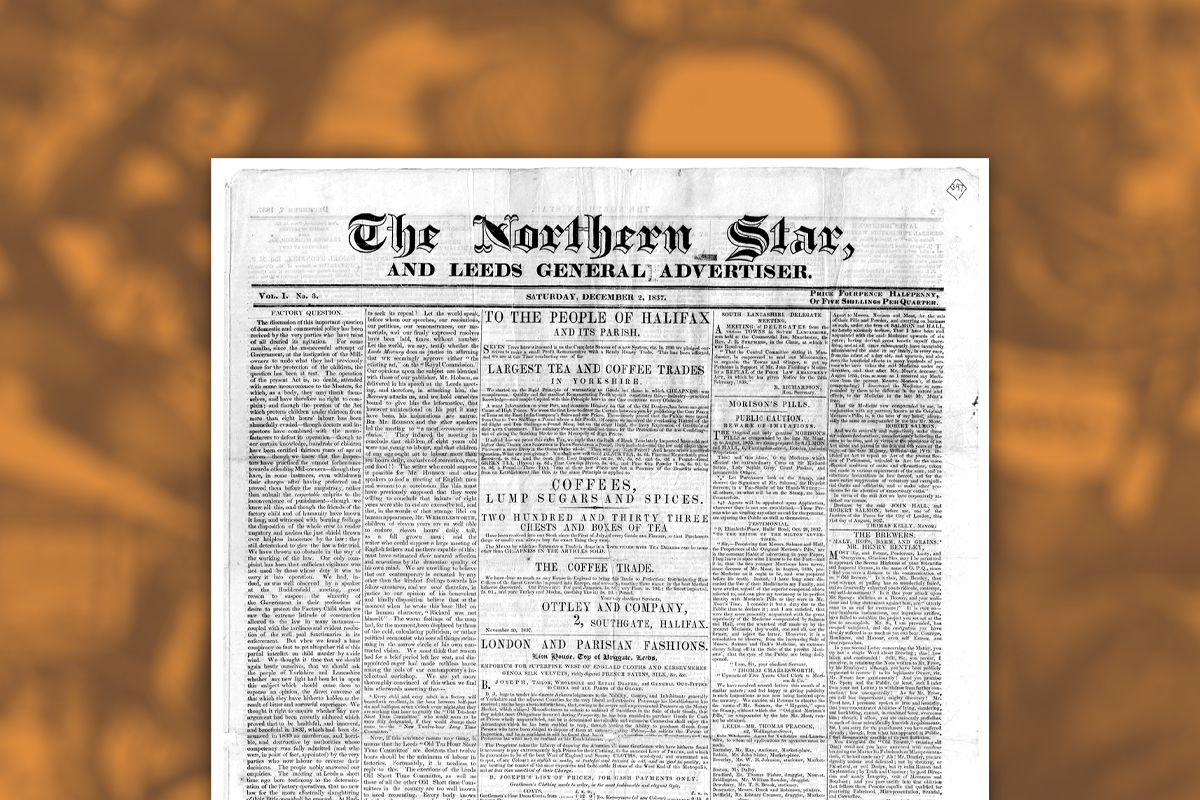

As such, many traditions were borrowed from the French Revolution, including the name of the revolutionary institution itself: the Paris Commune. This also included the particularly popular paper, Le Père Duchêne, both vulgar and humorous, which was named after the left wing Hébertist paper, Père Duchesne.

Revolutionary Paris

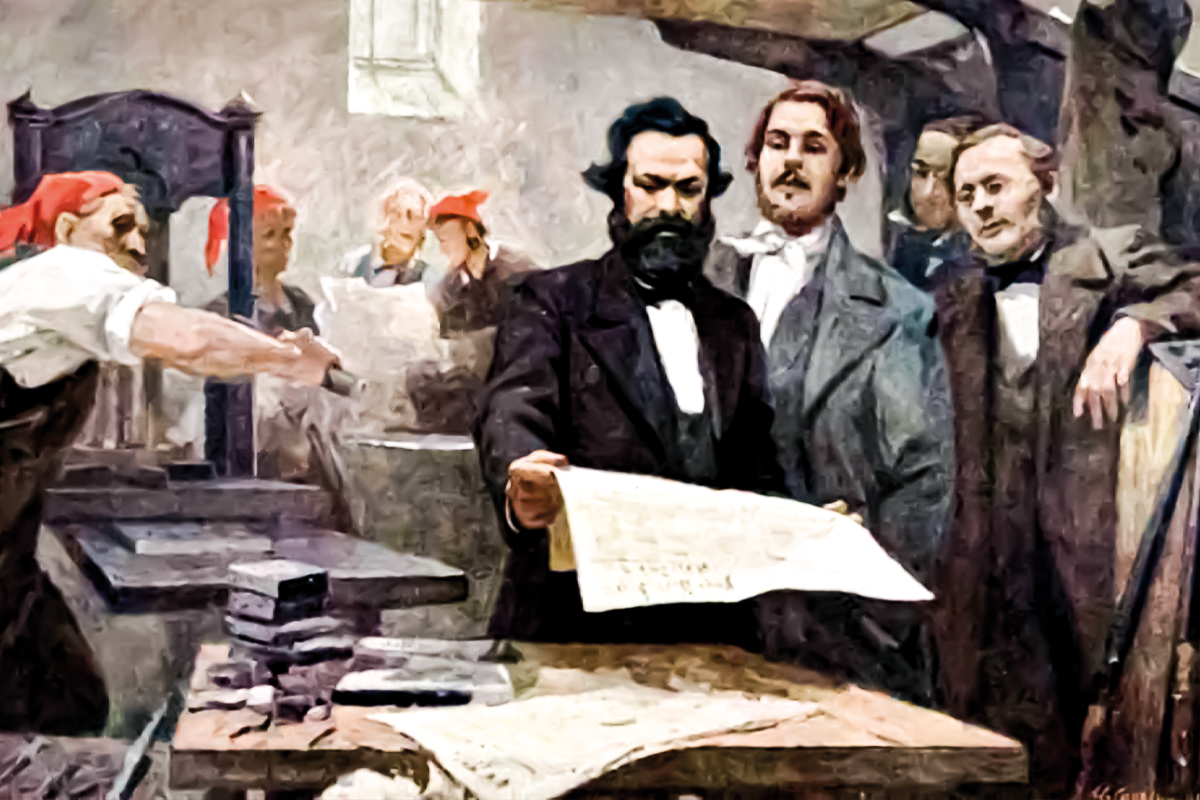

Radical publications flooded the streets of Paris, ranging from revolutionary bourgeois papers to independent communists.

One example was La Sociale, founded by Anne Jaclard, a Russian leader of the 1st International, living in exile in Paris. Another was the radical republican paper, Le Reveil, edited by Delescluze, who would become a prominent leader of the Commune.

The most important of all was Le Cri Du Peuple, a communist paper edited by Jules Vallès, also a member of the First International. The crisis in French society was fertile soil for these radical papers to grow.

By 1870, Louis Bonaparte’s regime – sensing its waning support – had waged a war to whip up nationalist sentiment in France against Bismarck of Prussia. It had the opposite effect. The war was a disaster from the outset. A bourgeois Government of National Defense appointed itself, which only exacerbated the class polarisation in society.

Bismark’s forces advanced and began a brutal siege of Paris. As the bourgeois government prepared to begin secret negotiations with the Prussians, word got out and the Parisian masses took matters into their own hands. The workers of Paris revolted along with the Parisian National Guard.

The army met them with live ammunition, it was a massacre.

Two key radical newspapers were suppressed by the National Government at this time – Le Reveil, by Delescluze, and Le Combat, by Pyat. Alongside this, 83 revolutionaries were arrested. The ruling class feared the revolutionary potential in the situation.

Stand-off

State repression opened the floodgates to the pressure that had been building up over that whole period of crisis. The class struggle now had a logic of its own, a revolutionary stand-off was inevitable.

All Parisians had been armed and conscripted into the National Guard for the war effort. The bourgeois government was rapidly concluding that the only way to save itself was to disarm Paris, and hand it over to the Prussians. They surrendered the city on 28 January, as terms of a peace treaty. But the workers of Paris never allowed it to be fully occupied.

Marx drew the same conclusion as the bourgeois, from the opposite class outlook:

“There stood in the way of this conspiracy one great obstacle – Paris. To disarm Paris was the first condition of success. Paris was therefore summoned by Thiers to surrender its arms…”

Elections were held to gain a mandate for their treaty with Prussia. Le Cri du Peuple saw through this charade, in an article titled ‘Peace’, it declared the opposite – class war:

“There is a victor and a vanquished, but the eternal antagonism of idleness and effort, of poverty and wealth, of parasitism and work, of capital and labour remain upright and threatening, mightier than triumph and above defeat.”

This paper was one of the most prominent in revolutionary Paris, its words circulated far and wide and drove the movement forward.

The very next day, the very same voice of the people applauded the Parisian National Guard for its stand with the workers, and implored it to cement its new revolutionary allegiance.

“National Guardsmen of Paris, the world is watching you, and we who love the fatherland and the republic acclaim you!”

9 days later, heeding these words, the National Guard of Paris established a central committee, which declared itself in opposition to the government of Versailles. Le Cri Du Peuple hit the streets the following morning, with an article titled ‘the vote’.

Every morning, the revolutionary press worked tirelessly, informing the people of every step taken. Thus unfolded the pioneering work of constructing a workers state.

Mistakes

The written word – in decrees, minutes, leaflets, and newspapers – was the lifeblood of the Commune itself. But by spreading the demands of the leadership, they also spread its mistakes.

The revolutionary press is essential, but the correct content and leadership is decisive. The blood circulates the body, but if weak in minerals, the body cannot live for long.

No party had been prepared in advance. The leadership was a hodgepodge of individuals with contradictory ideas. Some were revolutionary workers, with fighting instincts but little experience. Others were radical petty-bourgeois republicans, with high ideals but no decisiveness.

Many opportunities were missed in those weeks which inevitably doomed the Commune. As one faction of the Central Committee declared:

“We have only the mandate to secure the rights of Paris. If the provinces share our views, let them imitate our example.”

This was a declaration of suicide. Spreading the revolution, crushing the enemy, was essential when the momentum was with them. Marx recognised this danger, he wrote at the time:

“If they are defeated only their ‘decency’ will be to blame. They should have marched at once on Versailles, after first Vinoy and then the reactionary section of the Paris National Guard had themselves retired from the battlefield. The right moment was missed because of conscientious scruples.”

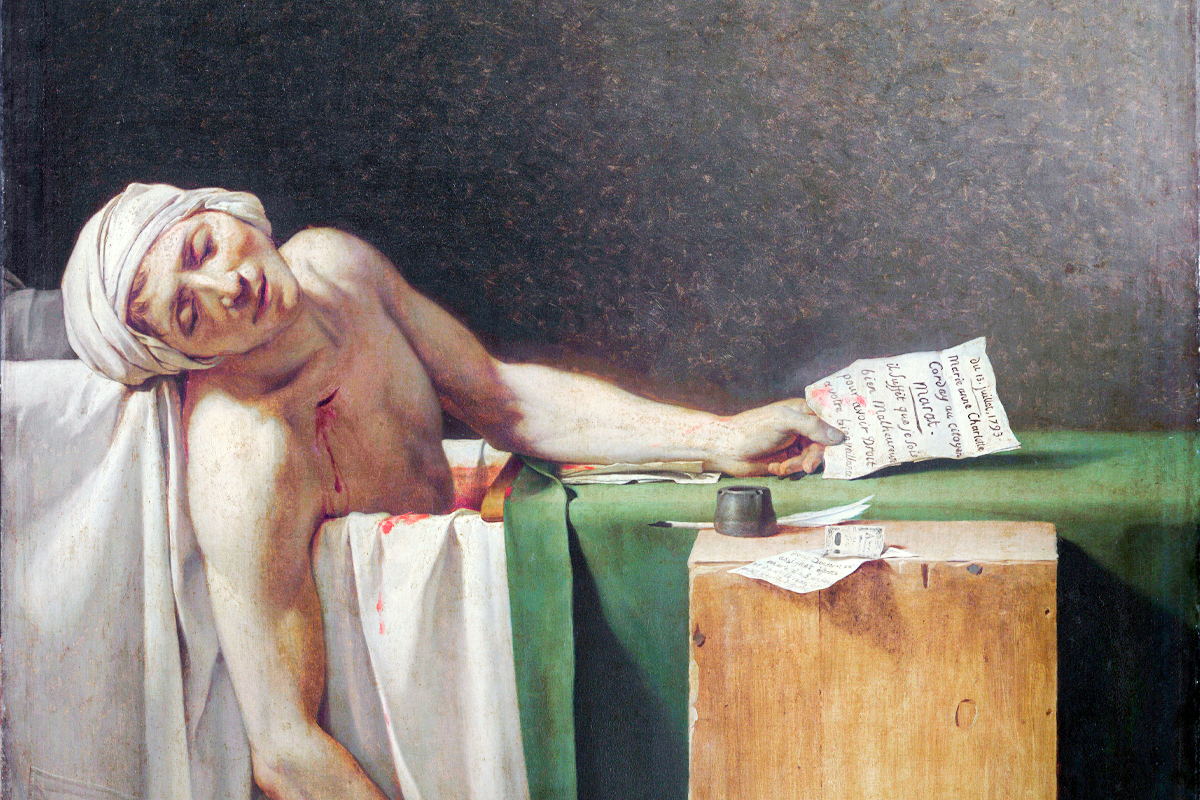

On 21 May 1871, the Versailles’ troops of reaction finally entered Paris. Delescluze, the radical republican journalist and leader of the commune, published the following, as soon as he heard:

“Make way for the People, for fighters with bare arms! The hour of revolutionary war has sounded … To arms, citizens! To arms! … The Commune is counting on you – count on the Commune!”

Unfortunately ‘the hour for revolutionary war’ was called far too late, and the commune was defeated.

The mass of revolutionary publications is not a mere historic relic, it has created a rich archive for any revolutionary today. Marx hungrily digested the literature of the Communards, and presented them in his great works.

Thanks to their sacrifices; their deeds, and their words, we have the advantage over them, and every revolution since. To the heroes of the Commune, we will honour their memory with a victory of our own – a revolutionary commune of the workers of the world.

Other entries in this series: