In 1450, in a modest workshop in Mainz, an inventor and craftsman named Johannes Gutenberg printed a German poem on Europe’s first moveable-type printing press.

At the time, Gutenberg was heavily in debt and in trouble with the law. He owed 800 guilders to a local moneylender Johann Fust (he was soon to borrow 800 more). But he had a plan to pay off his debts.

He immediately put the new technology to use, printing thousands of indulgences for the clergy.

Now, not only could the clergy scam people out of their daily bread with the promise of heaven for a small fee, but they could do so without having to painstakingly copy each word of their written certificate!

Gutenberg would go one step even further. In 1455 his workshop produced the world’s first printed Bible.

In an entirely predictable twist, he was rewarded for this with the immediate seizure of his workshop by the lender to whom he owed money.

Nevertheless, his efforts led the future Pope, Pius II to remark that Gutenberg was a “marvellous man”.

However, later, this convenient tool for the use of the church would completely transform into its opposite. Had Pius realised the impact that Gutenberg’s work would have only a century or so later, perhaps he would have been less complimentary…

Crisis of feudalism

It was not only the streets of Mainz that were dark, mildewy, and diseased. In truth, the whole feudal system was beginning to rot.

The ambitious middle classes – the traders, craftspeople and merchants who would one day develop into the bourgeoisie – had initially been strengthened by the guild system. Now, they were being held back by its regulations and conservatism.

The tiny principalities across the continent competed and disputed with the Holy Roman Empire, which was becoming old and moribund. And the peasantry faced constant humiliation and poverty.

As Engels explained, they carried the burden of the rest of feudal society on their backs, and were everywhere treated as a beast of burden, or worse.

Feudalism had relied on serfdom – the bondage of the peasants to the land. This had already been partially done away with by the end of the 14th century, due to the impact of the Black Death, the great European famine, and a series of peasant revolts.

In other words, from every angle, feudalism was outdated and going into crisis.

But one pillar of the feudal system still remained, as reactionary as ever: the Catholic Church.

So long as the Church held such great wealth, neither the princes nor the merchants could become the masters of society, nor could the masses of the peasantry be liberated from their feudal ties.

The clergy, the ideological representatives of the feudal system, held a monopoly on knowledge: reading, writing, and higher education. But the historic transformations taking place had robbed them of this.

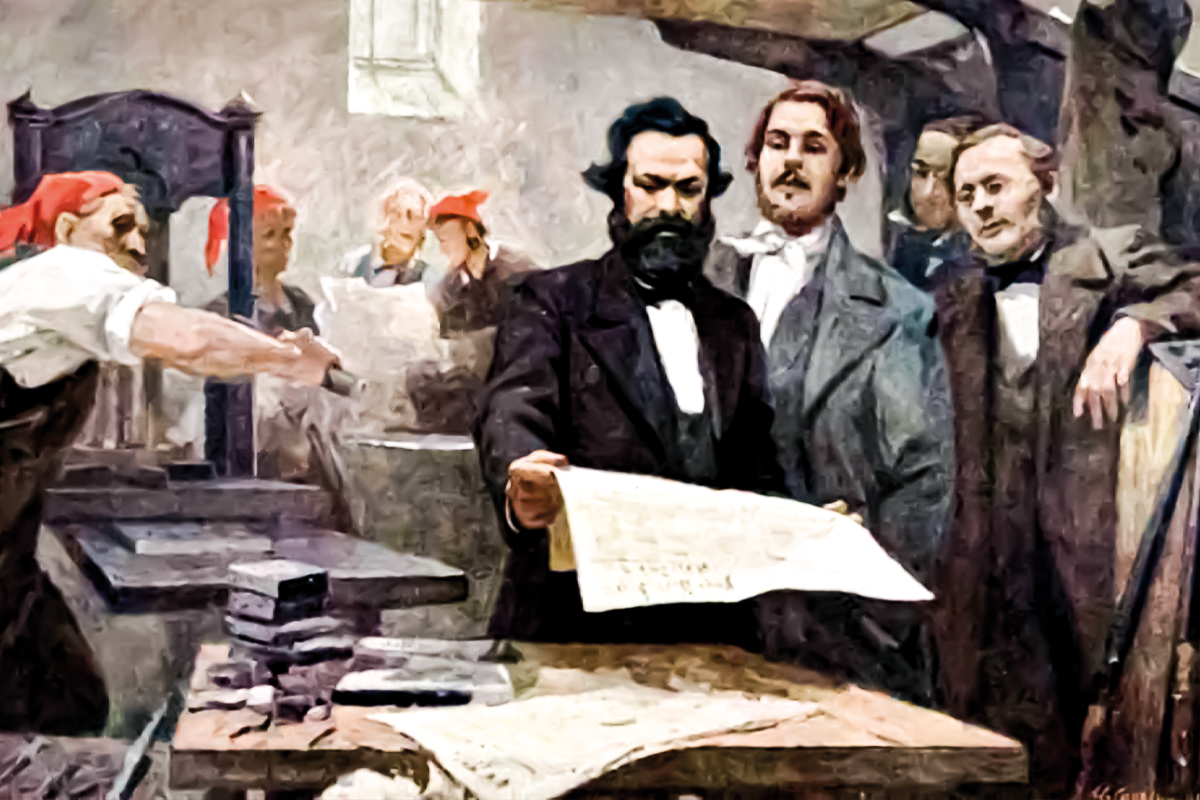

After Gutenberg’s invention, thousands of print shops sprung up across Europe. These produced not only religious texts, but also works on law, astronomy, philosophy, history, and literature like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

Many read (and criticised) the Bible for the first time. New ideas circulated more quickly than ever.

In the context of the crisis of feudalism, the printing press was guaranteed to become a catalyst for the spread of radical ideas, which expressed the dissatisfaction so many felt with the status quo.

The Reformation

The most decisive blow against the power of the Church was struck by Martin Luther, who published his 95 Theses in 1517.

He railed against the corruption of the Church. His Theses resonated with the poverty and frustration of the masses, in particular his 86th thesis:

“Why does the Pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?”

Luther was an overnight sensation. It was not just his theses that were published, but his sermons and pamphlets. They reached France, England and Italy, and were published in their hundreds of thousands.

Luther also helped publish the first complete translation of the Bible into German. Now, ordinary people could have direct access to the Scripture in a language they understood, instead of it being in Latin – the language of the intelligentsia.

Broadsheets pairing anti-establishment art with the words of radical preachers spread through Europe faster than the plague.

Two master engravers, the Beham Brothers, produced anti-church woodcuts in their Nuremberg workshop, such as the self-explanatory The Pope Goes Down Into Hell.

By 1524, the peasants, ambitious middle classes, and the disaffected nobility of Germany had taken up the banner of religious reformation, and turned it against the upper classes in a way that Luther himself had never predicted – and vehemently opposed.

Their manifesto, the Twelve Articles of the Peasants, was printed at least 25,000 times.

“Until now it has been practice that we have been treated like serfs,” it declared, “which is deplorable, since Christ redeemed all of us with his precious blood, both the shepherd and the nobleman, with no exceptions. Accordingly we hereby declare that we are free and want to remain free.”

Representing the most determined, revolutionary wing of the peasants and plebeians, a radical preacher called Thomas Müntzer fanned the flames of revolt against the rich and powerful, in a number of fiery pamphlets and proclamations.

“All the world must suffer a big jolt”, he wrote. “The game will be such that the ungodly will be thrown off their seats and the downtrodden will rise…”

“A wall of iron against the kings, princes, priests, and for the people hath been erected. Let them fight, for victory is wondrous, and the strong and godless tyrants will perish.”

Müntzer went one step further the task of tearing down feudalism, by putting forward a vision of a communist society:

“Omnia sunt communia (‘All property should be held in common’) and should be distributed to each according to his needs, as the occasion requires. Any prince, count, or lord who does not want to do this, after first being warned about it, should be beheaded or hanged.”

Ultimately, the Peasant War that broke out on this basis was not sufficient to overthrow feudalism, let alone establish communism.

As Engels explains in The Peasant War in Germany, the interests of the different classes participating were many and varied, and the conditions were premature.

In reality, this aborted struggle served to strengthen the power of the princes, and reinforce the backwards decentralisation of Germany.

But the damage had been done. The Church had begun to splinter. And despite its attempts to organise a Counter-reformation, the Vatican would never regain the authority it once had.

The rise of the revolutionary press

The printing press did not cause either the Peasant War or the Reformation. Interestingly, alongside the compass and gunpowder, the movable-type press had existed in both China and Korea for centuries beforehand.

But there, the press was in the hands of a completely reactionary class; the lumbering Imperial state and its bureaucrats.

Indeed, in Korea, the use of the printing-press for commercial profit was actually banned, and so it was used exclusively to print state edicts and the occasional religious document.

In Europe the press became the weapon of the townsfolk – the germ of the future bourgeois class. They could use this technology to raise their own revolutionary ideas, and bring about a blossoming of culture on a scale not seen since antiquity.

From this time on, the printed word would become the main vessel through which revolutionary ideas spread through society. The process that began on the continent would find its greatest expression yet in the English Revolution.

To be continued…