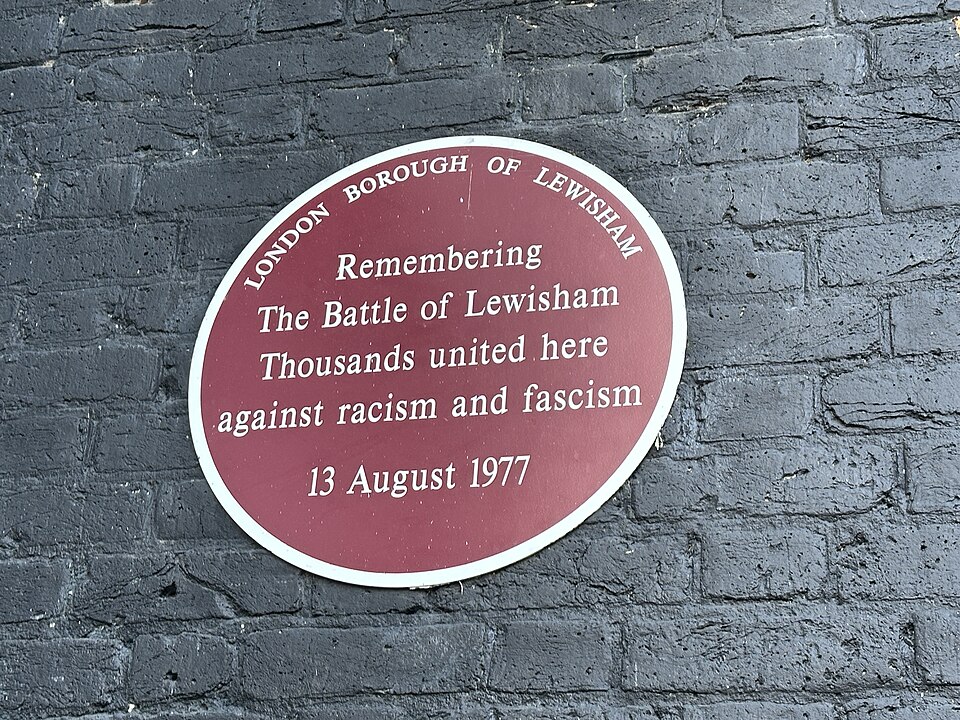

On 13 August 1977, the fascist National Front (NF) organised a march through the London Borough of Lewisham.

Local socialists, trade unionists, and community organisations fought back in what became known as the ‘Battle of Lewisham’, marking a turn of the tide against the NF.

Having welcomed cheap black and Asian workers from the colonies to help rebuild war torn Britain, the British ruling class now scapegoated these same immigrants – and their British born descendants – for Britain’s social malaise, and claimed they were responsible for the 1.3 million people unemployed in the mid-1970s.

In turn, the late ‘60s and ‘70s in Britain marked a resurgence of the far right. Behind their support and growth was the British state and ‘respectable’ society. The history books focus on Enoch Powell, but it was more than just a few ‘bad apples’. Racism was endemic in the British establishment.

In 1972, Labour-run Leicester city council took out an advert telling Asians to not settle in the city. ITV produced racist sitcom ‘Love Thy Neighbour’. The Daily Mirror warned about a “new flood of Asians to Britain” and the “lure of crime for the jobless young blacks”.

Rise of the National Front

This provided fertile ground for the NF, which formed as a merger of various far-right groups. Their aim was summed up by NF organiser Martin Webster, who admitted in 1972 that they were “busy setting up a well-oiled Nazi machine in this country”.

The NF regularly carried out attacks and marches of intimidation on Asians and black people. Yet they were never able to grow beyond a peak membership of 17,500.

This is primarily because they tried to build in working-class areas, and the victory over fascism in WW2 was still fresh in people’s minds.

Rather than being demoralised, the working class and its organisations were growing ever more militant as the crisis of the ‘70s wore on.

But the NF had yet to be given a knockout blow. For example, at one of these marches through Holborn in June 1974, 900 NF members were protected by a Praetorian Guard of around 1,000 police officers, while the counter-demonstrators numbered 1,500 at most – one of whom ended up being killed in the clashes with the police.

The weak response toward the fascists, combined with their tacit support from the ruling class, encouraged them to go on the offensive. And they set their sights on south east London, with its large black population.

The NF organised election campaigns calling for “a complete stop to all further coloured immigration and for total repatriation of the coloured immigrants and their descendants”.

Running on this vicious programme, they won 18 percent of the votes in the 1976 Deptford by-election. They only missed out on the council seat due their vote being split with the National Party, another fascist group.

Local opposition

In response to these election results, the All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (ALCARAF) was formed.

This was a popular front made up of a motley crew of groups: from the Labour and Communist parties, to the Liberal Party, local churches, and the Lewisham Council for Community Relations – to name a few.

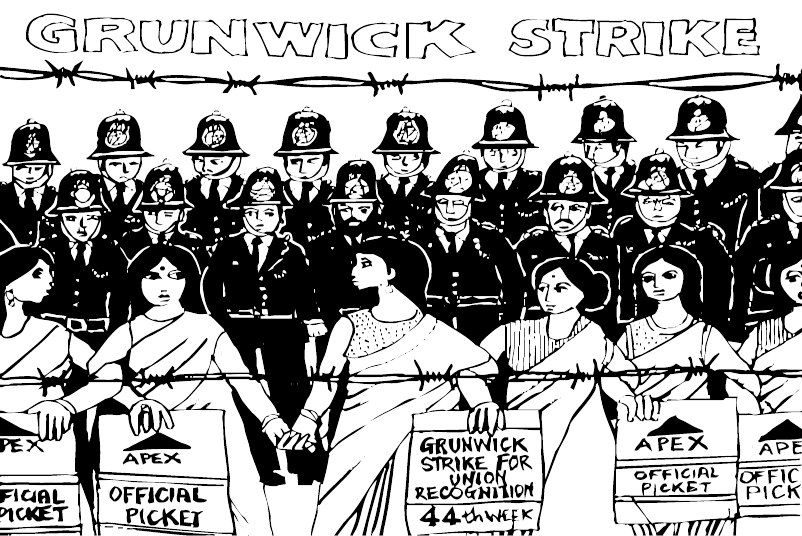

ALCARAF played a positive role in providing an opportunity for local black youth to get organised alongside workers, socialists, and trade unionists to fight racism. However, this popular frontism (all under one banner) created an eclectic mix of groups, resulting in political confusion.

For example, ALCARAF would try to educate people on anti-racism by presenting the struggle as one between ‘sensible’ people and ‘evil’ people. From there, it followed that anti-fascists should try to appeal to the consciences of the police and Home Secretary to take action against the fascists.

The problem was that it was precisely these people who were whipping up racism to begin with. The police were widely known to be sympathetic towards the NF, if not members themselves.

One ex-police officer in Steve McQueen’s recent documentary Uprising recalled how an officer showed off his NF badge before going to ‘police’ one of their marches.

Prelude to the Battle

The NF planned a march through Lewisham following the home raids and arrests of 21 young black people in the area: the ‘Lewisham 21’.

In this deliberate publicity stunt, the police charged them with ‘conspiracy to rob’, claiming that they were part of a ‘gang’ responsible for “90 percent of the street crime in south London over the past six months”.

This was music to the ears of the NF, who quickly adopted the slogan ‘muggers out’ as a racist dog whistle against black people.

In response to these racially-motivated arrests, and the growing threat and terror of the NF, the local community set up the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee.

They fought not just for the charges to be dropped, but also for an end to the racist ‘sus’ laws that gave the police a carte blanche to stop-and-search black people, and for an end to youth unemployment.

At the same time, the NF began a wave of terror. The defence committees meetings were attacked, with one small local march ambushed by over 200 NF thugs. Black and Indian shopkeepers were also attacked; a local Sikh temple was desecrated; and the offices of the Militant Tendency saw an attempted bombing.

ALCARAF first tried appealing to the High Court to ban the NF’s march, under the 1936 Public Order Act, but to no avail. When this fell on deaf ears, ALCARAF and the Communist Party resolved to simply call for a peaceful rally at a nearby park in the name of pacifism.

But through experience – with growing NF terror, and racist propaganda and policies from all the pillars of the establishment – illusions in the police, courts, and politicians were burnt away.

This all led to pressure from the local community to intercept the march in the streets. After all, it was their safety that was being threatened, and they instinctively understood that a rally nearby would do nothing to stop the fascists.

In the end, a compromise was reached to organise both a peaceful march and physically stop the fascists in the streets.

Disgracefully, at this point, the Communist Party leaders said that they “totally opposed” the “provocative march”, denigrating it as a “ritual enactment of vanguardist violence”.

This showed how far they had degenerated since the Battle of Cable Street, where the Communist Party had played an admirable role, forming a united front with local trades councils and Labour Party branches on the streets.

On the day

On the day of the march, around 4,000 people gathered for the peaceful rally. One activist remarked that he had “never seen so many black people out on a political demonstration”. Chants of “the workers united will never be defeated” filled the air, as the anti-fascists marched onwards.

Police blocked counter-demonstrators, and stated that they had to go a different route, which would completely avoid the fascists. Those who did not comply would be arrested.

The liberals, along with the Communist Party leaders, leapt upon this excuse to try and stop the physical intervention. The police’s decision should be respected, they said, with protestors dispersing to leave the NF unopposed.

The more radical layers – including the Militant-led Labour Party Young Socialists – argued that the march should continue in spite of police opposition.

In the end, the ALCARAF leadership capitulated and announced to the marchers that they would change direction and disperse.

This did not dissuade most of the counter-demonstrators, who diverted around the police and regrouped to form a bloc of a few thousand.

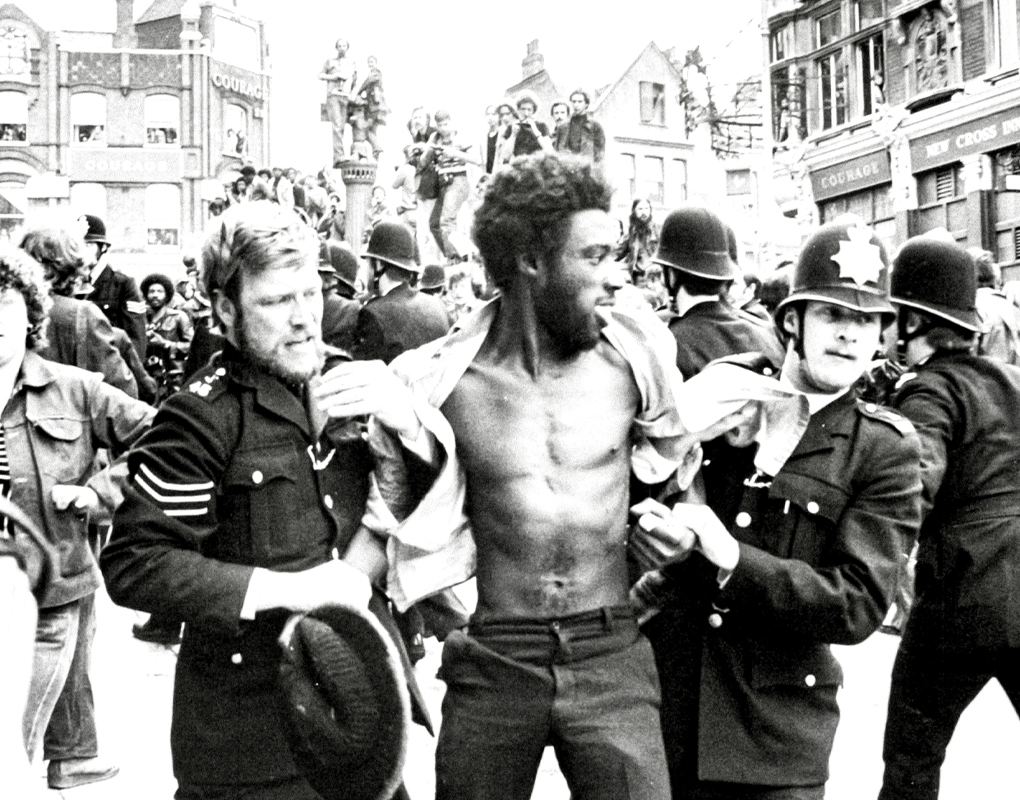

When the NF arrived, they were escorted by over 4,000 police, including the Special Patrol Group, riot squads, and mounted police. Without warning, the police charged into the counter-demonstrators, who responded with bricks, bottles, wood, and smoke bombs and beat up the fascists.

Although the majority of the NF got through, their march was split into two. Many of them fled after the initial confrontation with their tails between their legs.

Kevin Ramage, who was a leader of the LYPS and an active participant in the battle, recalls:

“The LPYS contingent was really well-stewarded, with the LPYS National Committee playing a central role.

“This discipline proved vital in a confusing and fast changing situation, with police horses charging into the protesters and smoke bombs being set off. Because we kept discipline and kept together as a contingent, it ensured that we were in the front line when the opportunity to confront a section of the NF march arose – and we gave them a kicking to remember.

“In the street battle that ensued, I Iost a lens from my glasses (I think I was hit by a copper’s arm), so I had to drive home afterwards with only one lens. If you know my eyesight, that was something to be avoided!”

Bourgeois hypocrisy

The real bloodshed happened once the fascists had fled and the community was celebrating their victory.

The police brutally attacked the anti-fascists again, despite the fact that the people they were protecting had already gone. In the end, 214 were arrested, with over 100 injured.

The papers before and after the march revealed the hypocrisy of the British establishment.

Before the march, the capitalist press gleefully supported the ‘democratic right’ of the fascists to march. But once the fascists were confronted, the press accused the left of starting the violence and being the same as the fascists.

The Daily Express even called for banning all marches and demonstrations!

A partial victory

Since the Battle of Lewisham, some have held it up as a decisive victory over the NF. In reality, it was only a partial victory, not a knockout blow.

The fascists continued their attacks for a number of years, particularly in south east London. They burnt down a youth centre and theatre that were frequented by black locals, alongside the infamous New Cross house fire in 1981, which killed 14 black youths.

Nevertheless, this inspiring struggle was a significant blow to the NF and the following year, the baton was passed onto east London. The infamous Battle of Brick Lane was to knock another crucial blow against the NF in the next chapter of our series.