Half a century ago, Mansfield Hosiery, a factory in the small Midlands town of Loughborough, became the unlikely site of a heroic struggle.

Indian workers at the factory overcame all the odds to become the first immigrant group to Britain to fight racism with mass militant strike action – and win.

Divide and conquer

Migrant exploitation was rife in Mansfield Hosiery, a garment factory which employed 700 people in Loughborough. Around 40 percent of the immigrant workforce were of Gujarati Indian descent, and had fled persecution in Uganda under the rule of Idi Amin. Their forced expulsion meant many arrived in England with little-to-no property.

These Indian workers held the lowest-paying jobs, such as bar-loaders, and were paid on a piece-rate basis. One of the first Indian workers hired by the factory, Jayant Naik, would only take home £32 weekly pay, despite working for the factory for 10 years. Meanwhile, white workers would be paid a regular wage of £50 per week as a knitter, even if they were with the company for much less time.

Indian workers would often be referred to as “oy, you”, instead of their actual name, and would face arbitrary unpaid suspensions. Women in saris were told to wear “English clothes or trousers”, and were often reduced to tears by their treatment.

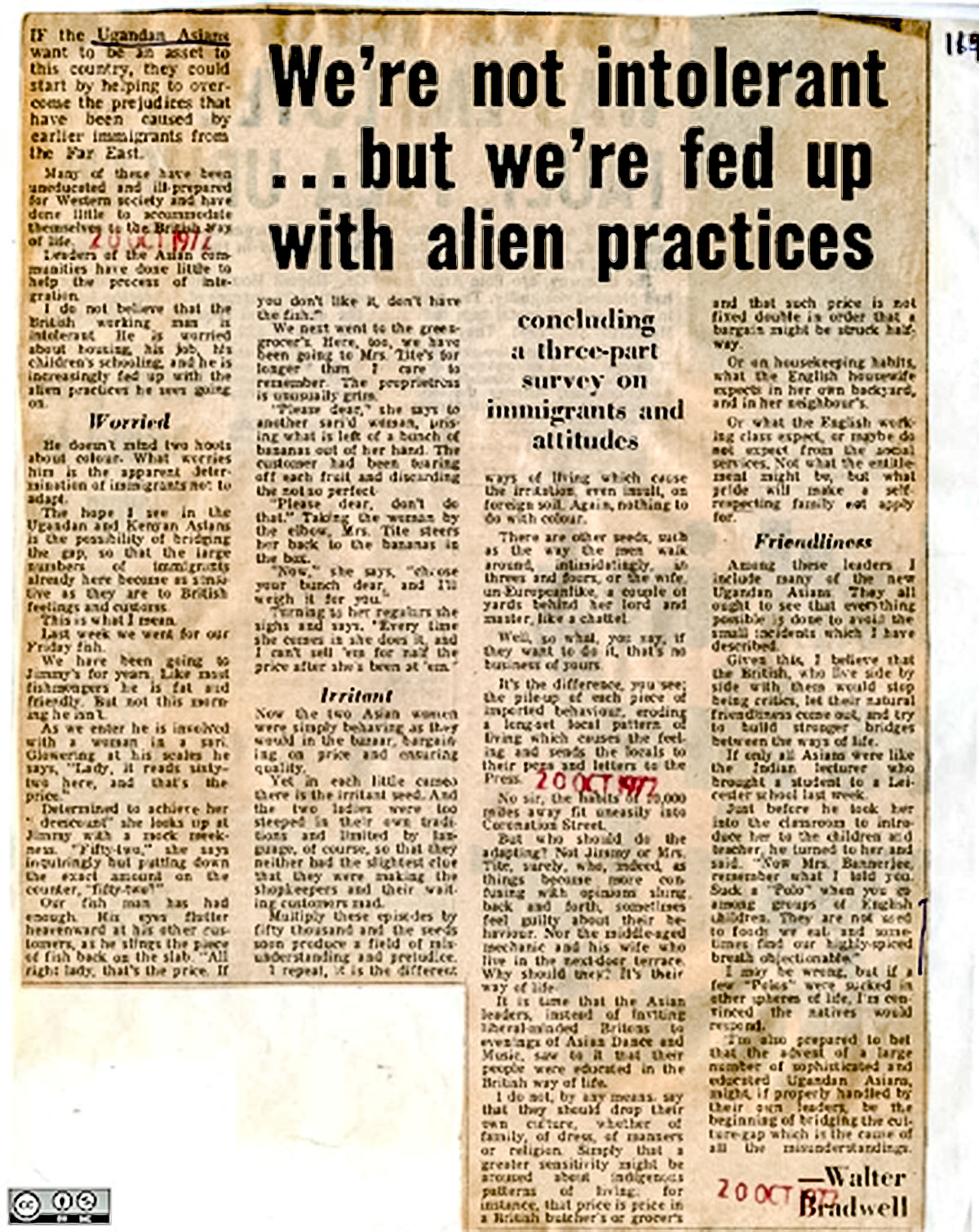

Moreover, immigrants in general were facing the blame for the end of the postwar boom. 1971 saw the passing of an Immigration Act, specifically targeting non-white Commonwealth immigrants. This significantly tightened Britain’s borders.

When the boom dissipated by the 1970s, economic growth was replaced with the beginnings of deindustrialisation. In Loughborough alone, two thousand workers were made redundant following factory closures in 1971. Inflation sat at seven to nine percent.

Faced with economic turmoil and growing class anger, the British establishment relied on a tried-and-tested tool of divide and conquer: racism.

In August 1972, for example, the Daily Express had a spread with the headline “Let’s look after our own first!”, with the subheading “Can nothing be done to stop this country being flooded with Asians?”

In 1968, Enoch Powell had made his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, where he warned: “In this country, in 15 or 20 years’ time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.”

Thousands of white unionised workers, most notably dockers, had marched and even went on strike for Powell.

Discrimination was prevalent in other forms of social life too. To maintain a white majority in the classroom, for example, schools would limit South Asian children to 30 percent of places. Some children would therefore have to be bussed off to faraway schools.

Taken together, this was part of a larger policy to scare white workers with threats of being replaced – both in the workplace and their community – by ‘Asians’.

Strike begins

While the main hosiery strike started in November 1972, the Asian workers, most of whom were Gujarati, illustrated their potential militancy and power a month earlier.

In October, a wildcat strike was started by the predominantly Indian bar-loaders – the lowest paid in the factory – after the bosses rejected their demand for a pay rise of £5 per week.

The workers won a pledge for no victimisation, no redundancies, and the false promise of no racial discrimination. When white workers were used as scab labour, the Asian workers went on strike again.

Later that same month, when two Indian workers were promoted to higher-paying jobs, the white workers in turn carried out a reactionary strike against their promotion! Much like today, bourgeois-driven paranoia about job-stealing immigrants had set into the minds of these white workers.

There was no antidote to this racist poison from the organised labour movement. In collusion with the National Union of Hosiery and Knitwear Workers (NUHKW), the bosses had the ‘offending’ Indian workers moved out of their jobs!

After years of discrimination, Indian workers would no longer endure their working conditions. As Mr Naik put it: “We had enough.” Emboldened by the wildcat strike of October, the workers went on strike again in November.

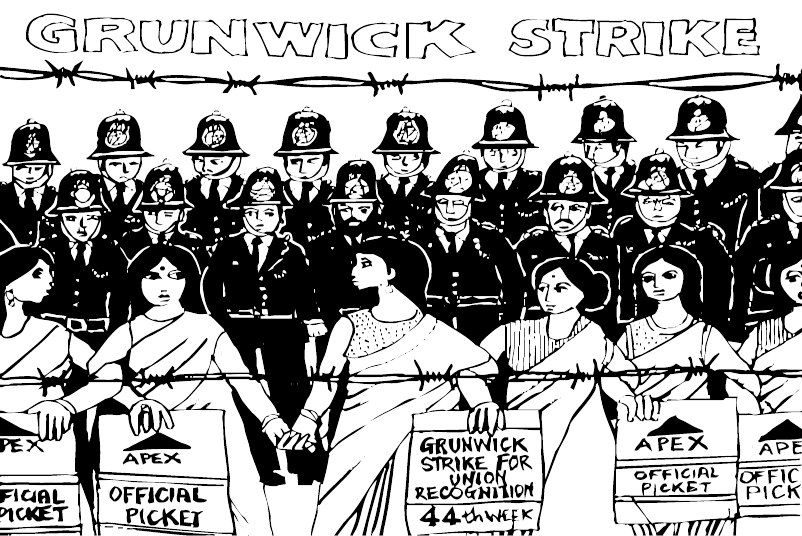

370 workers at the Trinity Street factory, including 50 women, downed tools in protest against poor pay and the colour bar on higher-paying jobs. Within days, a further 80 female workers came out on strike from a subsidiary factory on Clarence Street.

As one Indian woman striker put it: “The colour bar applies to us all. If our brothers are on strike, we have to give them support.” This solidarity across the gender divide saw Indian women strikers, usually seen as quiet and obedient, taking a militant and leading role.

In response, the bosses went door-to-door, asking strikers to return to the Hosiery. When this didn’t work, they resorted to bringing in 100 scabs with the consent of the union!

The strikers gained national – and even international – attention, with the strike reported in the New York Times! National support came from trade unions and student union branches, as well as the Black People’s Freedom Movement.

A strike committee was organised by Bennie Bunsee, a young South African anti-apartheid activist and self-described Marxist.

The workers learned they could only rely on their own strength. They organised a march through Loughborough and a demonstration outside Marks & Spencer, whom they accused of profiting from their exploitation.

Role of the unions

Nationally, the 1970s was a decade of militant unions and class battles. Britain came close to seeing an all-out general strike. 1972 saw victories at the Battle of Saltley Gate and with the Pentonville Five released, alongside widespread workplace occupations.

On the question of race, however, the unions were either indifferent or actively hostile. The Trade Union Congress (TUC) general secretary Victor Feather obtusely stated in 1970:

“The trade union movement is concerned with a man or woman as a worker. The colour of a man’s skin has no relevance whatsoever to his work.”

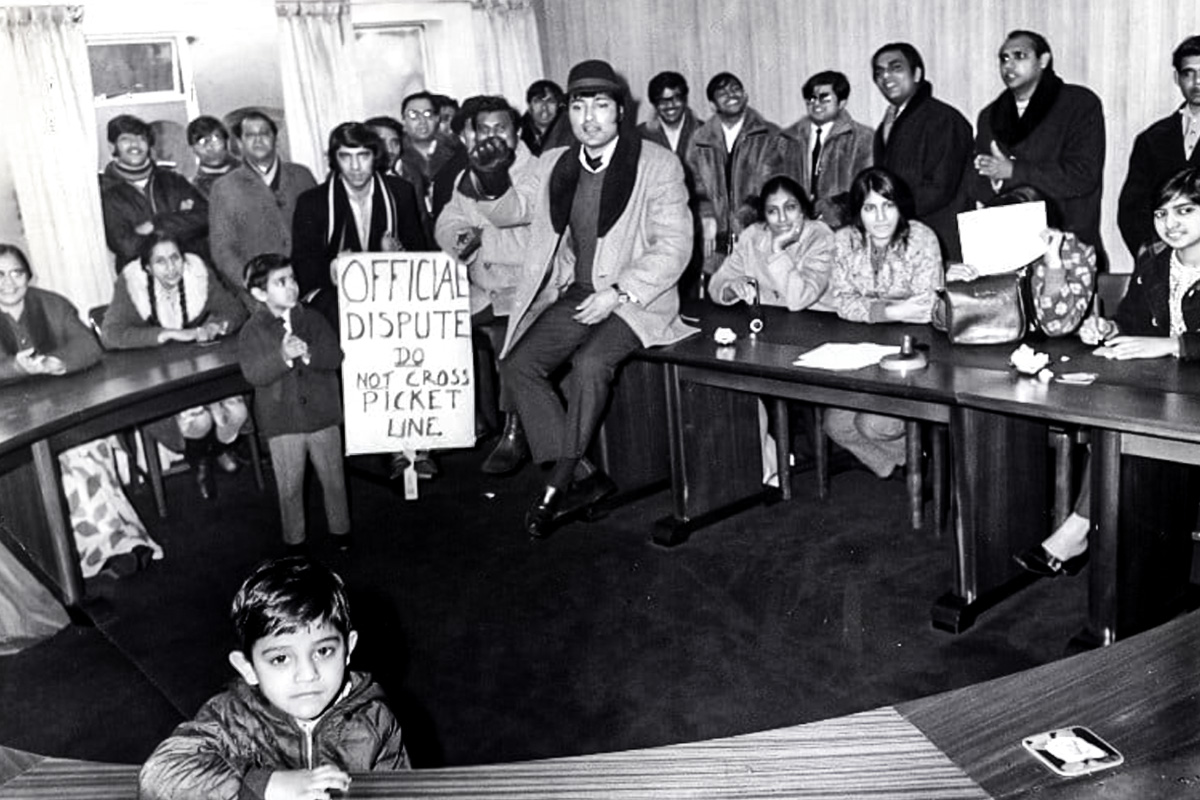

This attitude was reflected in the NUHKW, who were ready to end the strike on the bosses’ terms, describing the dispute as “blown out of proportion”. It was only the occupation of the union offices by women strikers that helped push the strike to be made official.

But even with the strike made official, white workers continued to scab.

Moreover, even when the strikers and their families faced starvation, the union only reluctantly agreed to gendered strike pay – £6 per week for men, and £4 per week for women – on the agreement that the workers would engage in arbitration. To their credit, the workers refused this condition.

The union leaders’ scandalous class-collaborationist policies hadn’t gone unnoticed, with the Engineering Union writing to the TUC to complain about the NUHKW’s collusion with management.

National Front

On the streets, racist thugs organised in the National Front (NF) engaged in ‘Paki-bashing’ and other forms of terror. By 1972, their national membership peaked at 17,500, spurred on by the British establishment, from tabloids, figures like Enoch Powell and unfortunately, even labour bureaucrats who aped their propaganda.

When the Mansfield strikers marched through the city, an NF counter-demonstration was organised, with the slogan “put Britain first”. This slogan was then outrageously the title of an article written by a NF member in the bulletin of the NUHKW!

Recognising the effects of the economic downturn on white workers, the NF consciously targeted working-class communities, with the labour leaders offering no alternative to the real reasons of the crisis.

On the factory floor, racism played a deeply pernicious role in undermining working class solidarity. Consequently, white workers would often cross these picket lines.

However the differences between the strikers and their white colleagues were not so deeply ingrained.

Indian workers like Mr Naik understood that “not all the white knitters are against us. But there are enough so that we had to fight.”

The Indian workers recognised that their main enemy was the bosses and focused on class-based tactics of strikes, demonstrations, and appeals for class solidarity. In fact, the New York Times reported:

“In the city itself, according to community relations officials, there have been few problems. Asians mix with whites in the public swimming pool and wander into the pubs, such as the ‘Generous Briton’ near strike headquarters. Asians and whites live in the same neighborhoods.”

Militancy pays

Hard pickets were used at the factory, with one case of a bosses’ van having its tyres punctured. Indian workers from nearby factories also threatened strike action, to add pressure.

The odds were stacked against the strikers. They faced the powerful propaganda machine of the bourgeois media, the far-right thugs of the National Front, white colleagues imbued with reactionary ideas, and the passivity of the union. However, the strikers refused to back down: “We will not go back like dogs.”

Militancy such as occupying the union offices to make the strike official, international media attention, and wider victories amongst the British working class in 1972 all spurred the mainly Indian workers.

This, alongside their strategic role in the factory, providing machines with thread and wool for the knitters, ended up cutting production by 70 percent, which in the end proved decisive.

After eight weeks, the strike was declared a success. The bosses conceded a pay rise, and the striking workers were granted the right to apply for higher-paying jobs. A shop committee was established, 11 of the 15 representatives being Indian men and women.

Turning point

For the first time in the post-WW2 era, immigrant workers went out on strike and won. The vital educational experience it provided led to the Mansfield Strike Committee, which included hosiery workers and local activists, giving advice to other immigrant disputes in Courtauld’s Mill, Preston, and E.E. Jaffee, Nottingham, in 1973.

Within six months of their victory, the committee also organised a national conference of Trade Unionists Against Racism. Behind the speaker’s podium, on a large banner, read Marx’s words: “White labour cannot be free while black labour is in chains.”

These actions clearly illustrate how it was black and Asian workers themselves who forced themselves into the British labour movement. In doing so, in fighting for their rights, they became conscious of themselves and their own power.

The inaction of the unions did not deter these workers from the class struggle, but rather renewed their effort to expel both racism and passivity from workers’ organisations. The conference ended with the following words:

“Now the talking is over and it is time for action… black and white both need each other, for if it is the black workers in the morning, it will be the white workers at noon.”

The impact of this strike, alongside other ‘race strikes’ of the 1970s, pushed the TUC to reform their race-blind policy at their 1973 congress.

The Race Relations Board, founded seven years prior to the strike, found discrimination by the union and the company. A separate government enquiry outrageously found all parties at fault. Fundamentally, however, the workers were vindicated through their own strike action.

Next time, we will explore how the precedent of Mansfield Hosiery spread to nearby Leicester – and exposed the neglected question of race in the British labour movement.