Three years ago in September 2022, Leicester made national headlines for communal clashes between Asians, initiated by a 200 strong march of Hindutva inspired fascists.

The march and clashes took place in the shadow of the Imperial Typewriter building, which still stands today on East Park Road.

The cruel irony of the act was that 50 years ago, this very area was the epicentre of one of the largest anti-racist strikes to rock Britain, led by Asians together.

Imperial Typewriters

Leicester in the 20th century was a manufacturing hub for hosiery, shoes and engineering. Imperial Typewriters, founded in 1908, epitomised this success.

Mohanbhai Mistry who worked in the Cam Auto department reminisced, “I started working Imperial Typewriters from 1966…For the typewriter, they used to make [everything] A too Z… making screws, rivets and nuts.”

By the 1960s however, with growing foreign competition and a failure to invest, the company was taken over by an American multinational, Litton Industries, for £1.9 million.

Litton deliberately turned towards the labour of Asians from the sub-continent and East Africa as a way to turn around affairs, which they did as profits trebled between 1968 to 1972.

Previously, the workforce had been predominantly white. But by 1974, around 1100 of the 1600 workforce was Asian and they were not treated equally, as they were not in society at large.

Bonuses were paid at 200 plus machines produced by Asians, whilst white workers only needed to produce 168. Targets were being increased. For Asians, higher paid positions were blocked, and relations between white and Asian workers were mixed. As Mohanbhai recalls:

“There was good relations, some of them. Some are, you know, awkward.”

May Day

Tensions had been building for years. Inflation was at 16 percent. And in February, Conservative Prime Minister Ted Heath lost the general election on a campaign of ending industrial action.

This all came to the fore at an incident at the Copdale Road branch of Imperial Typewriters, where a pay packet of a white woman worker was accidentally handed to her Asian colleague.

Shocked at the overt discrepancy in pay of the same grade, they turned to their Transport and General (TGWU) union rep, who condescendingly responded:

“You are ill-led and have done nothing but harm to the company, the union and yourselves.”

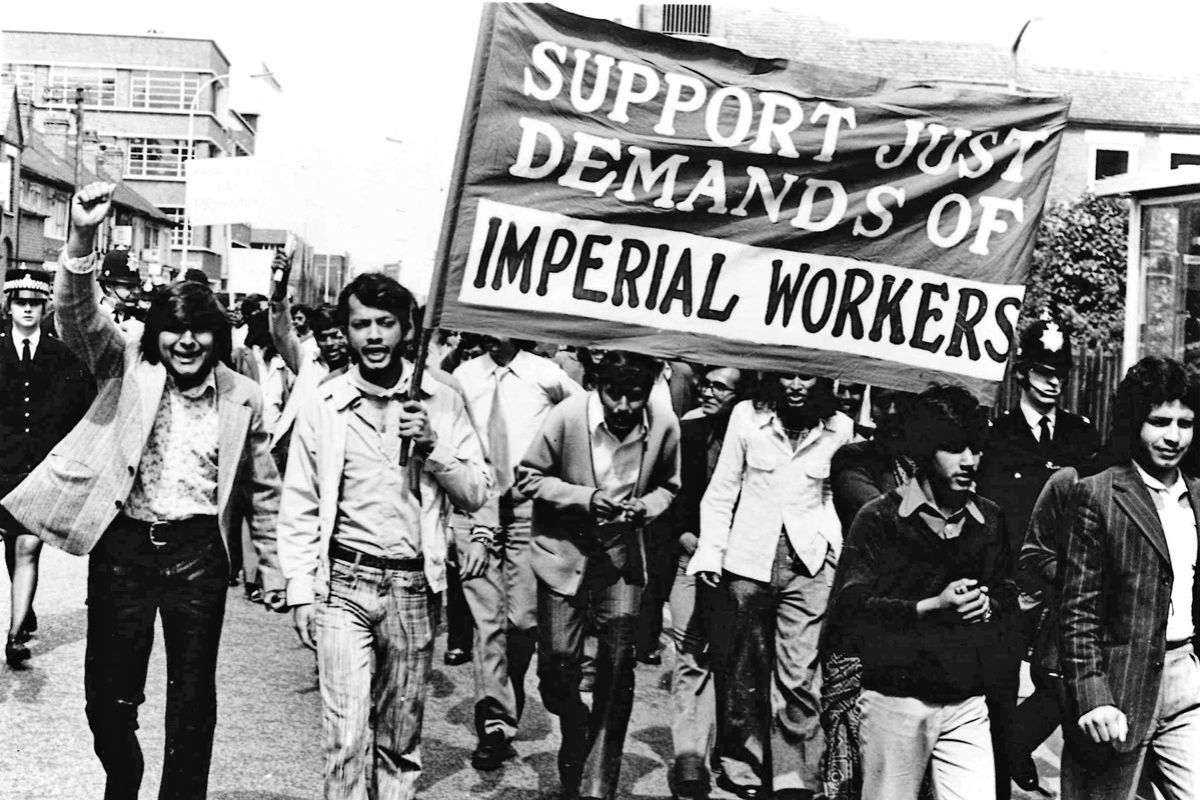

With grievances over bonuses, pay, and racial disparity, 39 Imperial Typewriter workers began strike action on International Labour Day 1974. They were joined by hundreds of workers at British United Shoe Machinery, Bentley Engineering, and General Electric.

In May 1974 hundreds of South Asian workers at Leicester’s Imperial Typewriter factory went out on strike after the discovery of wage discrimination. pic.twitter.com/wi85A5xolW

— Dripped Out Trade Unionists (@UnionDrip) February 22, 2023

The Imperial Typewriter workers subsequently continued to stay out on strike, and their forces quickly grew. But the TGWU refused to endorse the strike.

George Bromley, the TGWU negotiator and influential local Labour Party member, illustrated the opinion of the union bureaucracy:

“They have no legitimate grievances and it’s difficult to know what they want…in a civilised society, the majority view will prevail. Some people must learn how things are done.”

The TGWU were openly hostile, racist, refused strike pay, and colluded with the bosses. Bromley even spread a myth that the strike was funded by the Chinese Communist Party!

Bromley at a branch meeting admitted the strike was racial, but argued it was “coloured v. coloured”! Outrageously he claimed the Ugandan Asians who had been expelled by Idi Amin were “obviously used to a much higher standard of living” and were fighting against the majority of their membership who came directly from the subcontinent.

The British establishment were also quick to demonise the strikers as it became national news.

The Telegraph ran the headline: “No Colour Bar at Imperial Typewriters”, whilst the race relations board later denied racial discrimination. All of which fueled the fascist National Front, who had their offices on the nearby Humberstone Road.

Mohanbhai, remembering the era explained “it was a racial time. Because we were bullied in the school. Wogs and things like that.”

Power of labour

Over a week into the strike, management sacked 75 of the original strikers.

But despite the sackings and lack of official support, the strike continued to grow. 500 workers quickly joined, reducing production by half.

Asian women, stereotypically perceived as subservient, were the driving force of the strike, manning the picket lines, spreading the strike within the factory, and formed a women’s worker group.

‘Unofficial’ leaders, Hasmukh Kehtani and N.C. Patel, emerged, alongside South African anti-apartheid activist Benny Bunsee, who had been influential in the first successful immigrant strike at Mansfield Hosiery two years ago. Bunsee convinced Mohanbhai and his colleagues to join the fight.

Kethani and Patel held far more authority and legitimacy than the TGWU. Blocked from official channels, they organised grievance meetings which were taped by the strike committee, and used to create demands.

To answer Bromley’s smears of this being a ‘coloured v coloured’ dispute, Mohanbhai Mistry himself came directly from India, not Uganda, and there was enormous unity amongst the entire Asian community across all religious and geographic lines.

Four nearby factories with a predominantly Asian workforce pledged a 24 hour stoppage. They raised funds for the strike, as did organisations across the country like the Birmingham Sikh Temple because the strike became seen to be part of a wider struggle against institutional racism, including within the trade unions themselves.

On Sunday 19th May, a 2000 strong march was carried through Highfields.

#OtD 1 May 1974 hundreds of mostly East African Asian women workers at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester, England, began a 3-month strike. Although unsuccessful, it was a key moment in galvanising Asian working class resistance in the UK pic.twitter.com/801KY34PCl

— Working Class History (@wrkclasshistory) May 1, 2023

A key demand now placed front and centre was not just pay, bonuses and conditions, but freely electing shop stewards without the bureaucratic union rules which stymied black representation.

Union betrayal

The continual lack of support from the union, especially around strike pay, led to the strike ebbing and hundreds were starved back to work with little won in return.

Khetani had appealed directly to the former firebrand left wing militant Jack Jones who now led the union. But Jones at this time was using all his authority to hold back the labour movement.

He directly responded to not offer any official support to the strike because of divisions amongst the workforce – thereby pandering to the worst prejudices in the factory and society at large.

As Mohanbhai bluntly put it “yeah, they were useless.”

The strike committee appealed to the ranks of the TGWU through writing to local branches across the country, and 200 petitioned in front of the Labour Party headquarters, but they were met with silence and were left isolated.

Although funds given by Asian organisations across the country were generous, it was not enough to sustain hundreds of workers out on strike for a prolonged period of time.

Following a two week holiday over summer, picketing ended, and little was won in return. But Litton had a sting in the tail for all as they closed down the entire factory, including a plant in Hull, ending production for good.

A black union?

With all that happened, it may seem bizarre, but the strike committee put out a statement in defence of the union and against any notion of a separate black union.

For that to be explained, the context of the period needs to be remembered.

Trade unions were powerful organisations which had won big victories, including for Asian workers like Mohanbhai at the Imperial Typewriters in previous years.

A few months before the strike started, the vanguard of the British working class, the miners, had bought down the Conservative government of Edward Heath and won enormous pay increases.

Isolation from white workers and strike pay were key reasons for the defeat. In practice too, they learnt there were few other alternatives to fight as the strike bulletin reveals:

“Some of these people (and organisations) are like the rest of the race relations industry (Runnymede Trust, Catholic Committee for Racial Justice, Institute of Race Relations, Community Relations Councils, etc.). They set themselves up to fight discrimination but their actual task is to quieten things when they begin to hot up. They talk of backlashes, provoking the National Front—i.e. those who are racially abused must kowtow to this very abuse otherwise things will become worse. These colonial type organisations do not deter us whatever socialist garb they wear.”

The lesson was also not lost for Mohanbhai Mistry, who learnt: “If you fight for it, then you can get it.”

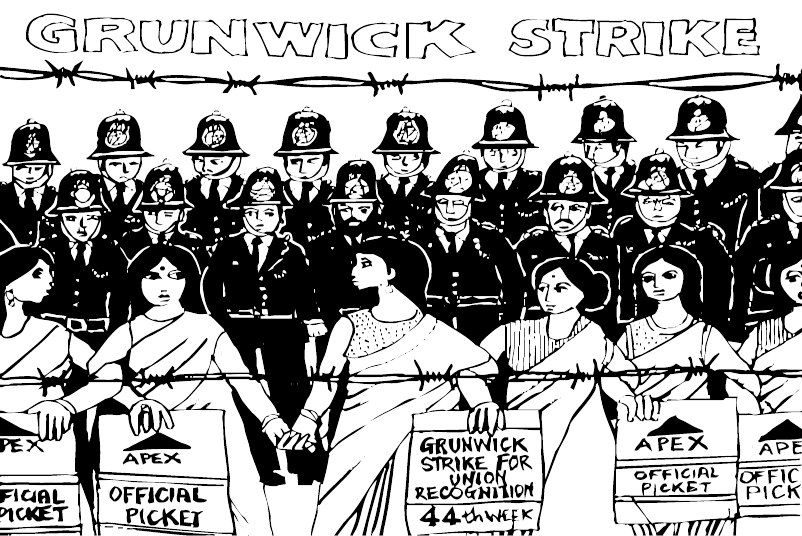

Seen in isolation, the Imperial Typewriters strike was a defeat. Yet in the grand scheme of events, it led to an unconscious reckoning amongst British trade unions and white workers, which was only fully realised two years later in Willesden, London.

The Grunwick strike was to take Britain by storm, which we will explore in our next instalment!