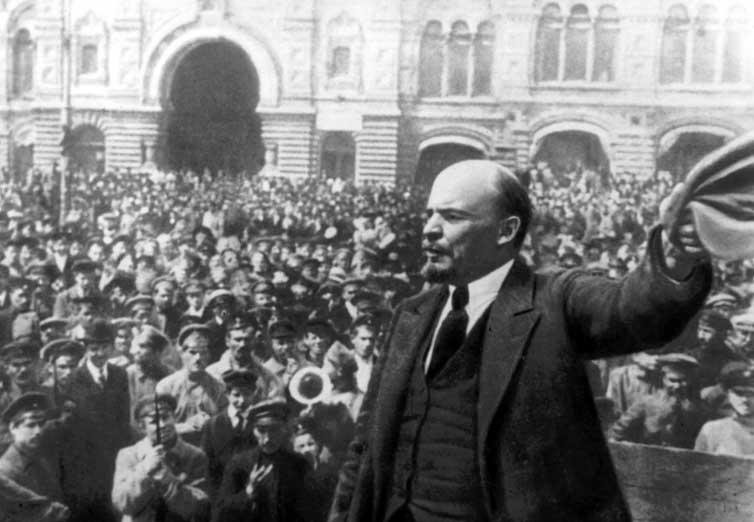

On 22 April 1870, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov – known more popularly as Lenin – was born at Simbirsk on the Volga. Today, exactly 150 years ago, marks the birth of this remarkable revolutionary, the greatest revolutionary of the 20th century.

He was the head of the first workers’ state in history, and his name is correctly synonymous with the world socialist revolution. His actions changed the course of world history.

Lies and slander

Ironically, today, as capitalism is in meltdown, there are also renewed fears in the ruling class that Lenin’s ideas of world revolution are becoming increasingly popular. That is why the slander against Lenin and the Bolsheviks has increased in intensity of late.

“During the lifetime of great revolutionaries,” wrote Lenin in State and Revolution, “the oppressing classes have invariably meted out to them relentless persecution, and received their teaching with the most savage hostility, most furious hatred, and a ruthless campaign of lies and slander.” This was the fate of Lenin – not only during his life, but also in death.

There has never been any figure in history who has suffered such slander and hatred from the ruling classes as Lenin. He personified Bolshevism and socialist revolution.

Unlike other socialists, the Bolsheviks under Lenin dared to put socialism into practice. In contrast, in August 1914, the leaders of the Socialist International betrayed the working class by supporting the imperialist war.

Lenin brought the real revolutionary ideas of Marxism to life. For him, Marxism was a guide to action. For this, for the October Revolution, the capitalists will never forgive him.

The very success of the October Revolution in Russia inspired millions, who were dying in the trenches of imperialist war.

Victor Serge was an anarchist in Spain in 1917, but he came over to Bolshevism. Serge relates an interesting conversation with a friend, Salvador Segui:

“Bolshevism,” Serge said, “is the unity of word and deed. Lenin’s entire merit consists in his will to carry out his programme… Land to the peasants, factories to the workers, power to those who toil. These words have often been spoken, but no one has ever thought seriously of passing from theory to practice. Lenin seems to be on the way…”

“You mean,” Seguí replied, bantering and incredulous, “that socialists are going to apply their programme? Such a thing has never been seen…” (From Lenin to Stalin, p.9)

Terror, tragedy or triumph?

Today, Lenin is slandered not only by the bourgeoisie, but also by liberals, reformists (left and right), anarchists and every other pseudo-radical trend.

Today, Lenin is slandered not only by the bourgeoisie, but also by liberals, reformists (left and right), anarchists and every other pseudo-radical trend.

With today’s terrible crisis, revolution is once again on the agenda. Lenin’s writings are more relevant than ever. They are a treasure trove of revolutionary strategy, theory and tactics.

Of course, the slanders of Lenin are many. There is a veritable cottage industry in churning out books – year in, year out – to attack Lenin and the Bolsheviks. There are literally hundreds of them, all making the same noises.

Without exception, such ‘historians’ all gnash their teeth in dealing with this great man. “The historian’s problem is that [it] is difficult to deal with dispassionately,” says Professor Pipes (The Russian Revolution, p.xxiii), in a gross understatement. This is a great excuse to attack Lenin, using all kinds of lies and distortions.

The historian Robert Service has the same difficulty. In his diatribe on Lenin, he says, “although this volume is intended as a balanced [!], multifaceted account [!], nobody can write detachedly about Lenin. His intolerance and repressiveness continues to appall me.” (Service, Lenin: A Political Life, vol.3,p.xix)

Lenin is written about as a fanatic; an extremely unsavoury character, who, according to them, was scheming ever since his childhood to get his hands on power. He had, they claim, all the traits of Robespierre in him.

“Here lay the germs of government by terror, of the totalitarian aspiration to complete control of public life and opinion,” notes Pipes, in a tale to frighten little children. (Pipes, p.349) Professor Robert Service also says that Lenin “relished terror”.

“Lenin had a strong streak of cruelty. It is a demonstrable fact that he advocated terror on principle, issued decrees which condemned to death countless people innocent of any wrongdoing, and showed no remorse at the loss of life for which he was responsible,” states Pipes. (Pipes, p.350)

Orlando Figes, another “expert”, makes the same point: “it is clear that many of the characteristics which he would display in power were already visible at this early stage.” (The People’s Tragedy, p.144) To be honest, his book A People’s Tragedy reads more like Orlando’s Tragedy.

Clearly, this man Lenin was a monster, a Genghis Khan! How stupid the Russian masses were to follow him.

‘Conspiracies’ and ‘coups’

Oh yes, let us not forget, “the obverse side of Lenin’s cruelty was cowardice,” according to our Professor Pipes, as he is reported to have fled when chased by armed cavalry. (Pipes, p.351) Clearly, our brave Professor would have stood firm against charging Cossacks on horseback.

The allegation that Lenin was in favour of “terror” is completely wide of the mark. He was opposed to individual acts of terror, which was the method, not of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, but the Narodniks and Social Revolutionaries.

Lenin was a Marxist and worked for the mass mobilisation of the working class and poor peasants against tsarism and to overthrow capitalism.

This idea that revolution is a ‘conspiracy’ of a minority is the idea not of Lenin, but of Blanqui and Bakunin. The Bolsheviks used agitation and propaganda to win over the masses. In 1917, they worked to win over a majority in the soviets, which they succeeded in doing. Socialism cannot be imposed by a minority, but must come from the will of the majority.

The bourgeois historians link this idea of a ‘conspiracy’ of a minority to the events of 1917, which is completely false. For them, the Russian Revolution was not a popular revolution with mass support, but simply a ‘coup’ or secret plot.

“What ‘uprising’ of workers and soldiers?” asks a surprised Pipes, despite the fact that the soviets, representing millions, took power into their hands. He describes the masses as “a mob”, eager to “loot and vandalise”, which is a complete fiction. The Soviet Congress, for him, was nothing more than “a rump”.

Figes repeats the same point, of course, as do all the bourgeois historians. The Russian Revolution was “in effect no more than a military coup.” (Figes, p.484)

But then Pipes is forced to admit that “the fall of the Provisional Government caused few regrets: eyewitnesses report that the population reacted to it with complete indifference. This was true even in Moscow…here the disappearance of the government is said to have gone unnoticed.” (The Russian Revolution 1899-1919, p.505) In other words, the Provisional Government had no support.

Even Figes has to say, “it must be borne in mind that large numbers were not needed for the task, given the almost complete absence of any military forces in the capital prepared to defend the Provisional Government.” (Figes, p.492)

So even these critics are forced to contradict themselves.

Revolutionary theory

We defend Lenin and his ideas, not because we are hero worshipers. We are not interested in the cult of the personality, which is alien to Marxism

We defend Lenin and his ideas, not because we are hero worshipers. We are not interested in the cult of the personality, which is alien to Marxism

Lenin was a genius in understanding and applying the ideas of Marxism. More than that, he developed Marxism – as for instance with his great work State and Revolution. Throughout his life he applied Marxism to the concrete situation that faced the revolutionary movement.

But as Trotsky once explained, Lenin was not born Lenin. Lenin made himself, by learning from his experiences and conquering the ideas of Marxism.

Lenin was deeply affected by the hanging of his brother, Alexander, for his part in the attempted assassination of the tsar. His brother, together with the youth of his generation, were influenced by the Narodniks, who tried to blow up the tsarist regime.

Lenin saw the weakness in this approach, however: for every tsarist representative killed, they would be replaced by another. Lenin instead was attracted by Marxism, which relied on the active participation of the working class to change society.

As a young activist, he organised Marxist study circles, and was eventually arrested and exiled to Siberia, as with so many who fought the tsarist regime.

After that, he went abroad to join the Marxist circle led by Plekhanov, who became known as the father of Russian Marxism. They established an all-Russian newspaper Iskra, around which they prepared for the establishment of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

In 1902, Lenin edited the paper in London. He learned the importance of organisation and theory. In the same year, he produced his pamphlet What is To Be Done?, which argued for professional revolutionaries and a party. “Without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement,” he wrote.

Bolshevism vs Menshevism

The allegation of Lenin being ‘dictator’ is complete nonsense. Lenin certainly had authority – but this did not come from waving a big stick. What he possessed was something more powerful: namely a political and moral authority. He possessed the power of ideas, nothing more.

The allegation of Lenin being ‘dictator’ is complete nonsense. Lenin certainly had authority – but this did not come from waving a big stick. What he possessed was something more powerful: namely a political and moral authority. He possessed the power of ideas, nothing more.

Lenin is attacked for displaying so-called ‘ruthlessness’ at the Second Congress of the RSDLP (in reality, the founding congress) in 1903, where a split took place between the ‘hards’ and the ‘softs’, Bolsheviks and Mensheviks.

This split was over the rules and composition of the editorial board of Iskra. Lenin did not want a split, as there were no political differences. However, the split was to foreshadow – to anticipate – the future political differences between revolution and reformism.

Few, if any, realised its significance at the time. Basically, it was an attempt by Lenin and his supporters to establish a more professional party, as opposed to the loose, inward-looking mentality of a small circle or group.

Lenin attempted many times to heal the split between the two wings of the RSDLP. But there were definite political differences.

1905 was a turning-point. The events of 1905 revealed to Lenin the importance of the ‘soviets’, or workers’ councils, which had sprung up. He saw in them the basis of workers’ self-rule.

The revolution also allowed for the abandonment of the old underground methods of work, and the need to open up the party to new layers. Lenin saw the 1905 revolution as a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the 1917 October Revolution.

But following the defeat of the 1905 revolution, the political differences between Bolshevism and Mensheviks widened – especially the perspectives for the Russian Revolution. Both knew that Russia faced a bourgeois democratic revolution. But which class would lead it?

The Mensheviks said the bourgeoisie, and that the young Russian working class should play a subordinate role. Lenin, on the contrary, argued the Russian capitalists were opposed to revolution and only the working class could lead it.

Lenin therefore called for a “Democratic Dictatorship of the Proletariat and Peasantry”. In his view, a successful bourgeois revolution in Russia would give an impetus to the socialist revolution in Europe, which in turn would affect developments in Russia.

Trotsky held another position, called the theory of the Permanent Revolution. He believed, like Lenin, that only the working class could lead the revolution. However, Trotsky said that the workers – once in power – would not stop at bourgeois democratic demands, but would immediately move on to socialist demands. This ‘bourgeois’ revolution would grow over to be a ‘socialist’ one, and become ‘permanent’. It would spread to other countries, as the material basis for socialism only existed on a world scale.

While Lenin continued to build the Bolsheviks faction, Trotsky remained outside of both factions, but was much closer politically to Lenin.

Principles and the party

In these years, Lenin argued against liquidationism – the dissolving of the party into the wider amorphous movement. He also fought against those arguing for political boycotts. This was an ultra-left attempt to spurn legal opportunities. Both opportunism and ultra-leftism, Lenin explained, were head and tail of the same coin.

In these years, Lenin argued against liquidationism – the dissolving of the party into the wider amorphous movement. He also fought against those arguing for political boycotts. This was an ultra-left attempt to spurn legal opportunities. Both opportunism and ultra-leftism, Lenin explained, were head and tail of the same coin.

Lenin was an orthodox Marxist and fought against all attempts to revise it. In this, he was – correctly – very hard.

He led a struggle to defend dialectical materialism within the party, against Bogdanov and Lunacharsky, who tried to promote ‘new’ ideas and philosophy. In 1908, he wrote Materialism and Empirio Criticism as a response.

Lenin provided the theoretical anchor to the Bolsheviks. Every question, every difference, was used to raise the political and theoretical level of the party for the tasks that laid ahead. His Collected Works of 45 volumes are a testament to his efforts.

It is so much nonsense that Lenin created an authoritarian regime in the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks were very democratic, as was the party later. There were many debates and differences.

There were recognised factions; and even Lenin could find himself in a minority. Bukharin led a faction against the Brest-Litovsk Treaty in 1918 and even had his own daily paper! All he had was the power of ideas and persuasion.

The split between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks did not take place formally until 1912. This took place two years before the split in the International.

The split in 1914 was over the betrayal of the International leaders supporting the imperialist World War. Lenin and the internationalists were reduced to a handful. Lenin denounced the old leaders in the sharpest terms for their “social patriotism”. Even at this stage, Lenin called openly for a new Third International based on clear revolutionary principles.

War and revolution

The war years were especially difficult, given the betrayal and isolation. However, war also produced revolution.

The war years were especially difficult, given the betrayal and isolation. However, war also produced revolution.

This broke out in Russia in February 1917. Soviets were again created, and the tsarist regime was overthrown. All the revolutionaries returned from exile.

But Lenin had drawn new conclusions, which coincided with those drawn independently by Trotsky: that there needed to be not a bourgeois revolution, but a new, socialist revolution in Russia. This revolution could not be contained to “socialism in one country”, but must be the beginning of the world socialist revolution.

When Lenin argued for this change he was in a minority of one in April 1917. His ideas were published in his April Theses, which abandoned the old perspective in favour of “permanent revolution”.

We have all this wild talk that Lenin was in favour of terror, with quotes ripped out of time and context. But in 1917, his whole approach can be summed up with his slogan: “patiently explain!”

Rather than a “coup”, Lenin argued that the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries – who had a majority in the soviets at this time – should take power. Lenin argued for a peaceful revolution. Once the old order was overthrown, Lenin argued for a peaceful struggle within the soviets as to what programme to adopt.

But the soviet leaders opposed this and took measures to suppress the Bolsheviks in July. This encouraged the military, led by Kornilov, to move against the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks rallied to fight off the counter-revolution. Their slogans “Bread, Land and Peace!” and “All Power to the Soviets!” were gaining ground.

Eventually, the Bolsheviks won a majority in the soviets, which prepared the way for the October Revolution. All this was done under Lenin’s guidance.

Trotsky was put in charge of the insurrection itself. The revolution was an entirely bloodless affair, at least in Petrograd. It was in effect a peaceful revolution, despite the insinuations of the bourgeois historians. It was not a coup, and no one raised a finger to defend the Provisional Government.

This was the first successful socialist revolution in history – leaving aside the brief episode of the Paris Commune. The Bolshevik Party, Lenin, and Trotsky led the revolution and established a workers’ state. However, this was only the first shot in the world revolution. They went on to establish the Third International, as the party of world revolution.

Civil War

Of course, the capitalists could not tolerate this! They sent in 21 foreign armies to overthrow the Soviet government. The workers had no alternative but to defend themselves against the intervention and the counter-revolution of the ‘White’ generals.

Of course, the capitalists could not tolerate this! They sent in 21 foreign armies to overthrow the Soviet government. The workers had no alternative but to defend themselves against the intervention and the counter-revolution of the ‘White’ generals.

It was the imperialists who promoted the Civil War. They are to blame for the deaths and misery caused. They butchered, raped, and skinned alive those who supported the Bolsheviks, as was witnessed in Finland in 1918.

It was a fight to the death, not a middle-class tea party. It was certainly not a question of turning the other cheek. If the Bolsheviks had lost, there would have been rivers of blood and countless deaths. The counter-revolution would have shown no mercy. The German imperialists had already seized huge amounts of Russian territory.

The Bolsheviks in fact were very soft in the early period, allowing counter-revolutionary generals to go free! They broke their promises and again waged war on the Reds. Lenin was shot in 1918 and Trotsky’s train was nearly blown up.

It was this that forced the Soviets to hit back and launch the ‘red terror’, as a matter of self-defence. They were forced to introduce ‘war communism’, where grain was requisitioned to feed the starving cities.

The Civil War lasted from 1918 until 1920, causing terrible death and destruction. It was during the Civil War that the bourgeois parties, including the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries were banned. The reason was that they openly supported the counter-revolution. In the same way, in the Second World War, Britain banned the British Union of Fascists and imprisoned Oswald Mosley.

Rise of Stalinism

Unfortunately, the revolutionary wave of 1917-21 was defeated. The Soviet Republic was isolated in a backward, devastated country. This reinforced the growth of bureaucracy. Millions of communist workers were killed in action. Under imperialist blockade, starvation was rife.

Unfortunately, the revolutionary wave of 1917-21 was defeated. The Soviet Republic was isolated in a backward, devastated country. This reinforced the growth of bureaucracy. Millions of communist workers were killed in action. Under imperialist blockade, starvation was rife.

The only thing the Bolsheviks could do was to hold on until help came in the form of revolution in the West. Lenin even said he was prepared to sacrifice the Russian Revolution for a successful revolution in Germany.

With the growth of bureaucratism, and terrible economic conditions, the working class was squeezed out. Stalin increasingly became the figurehead of this bureaucracy.

Lenin’s final struggle before his death was a bloc with Trotsky against Stalin and the growing bureaucracy. Lenin, on his deathbed, broke off all relations with Stalin. In his last testament, he called for Stalin to be removed as general secretary.

With Lenin’s death and the defeat of the European revolution, Stalin moved to consolidate his power. Trotsky – who fought for Lenin’s ideas – was expelled, together with the Left Opposition. This led to the bureaucratic degeneration of the Russian Revolution and the rise of Stalinism.

Lenin’s ideas were either abandoned or twisted to justify the crimes of Stalin and the bureaucracy.

Of course, the bourgeois historians fall over themselves to equate Bolshevism with the later crimes of Stalinism. “I devote considerable attention to these… antecedents of Stalinism, which, even if only imperfectly realised under Lenin, from the outset lay at the very heart of the Russian Revolution.” (Pipes, p.xxii).

Professor Figes also chimes in: “it is clear that the basic elements of the Stalinist regime—the one-party state, the system of terror and the cult of the personality—were all in place by 1924.” (Figes, p.807) And again, “one can draw a direct line from this serf culture to the despotism of the Bolsheviks.” (Figes, p.809)

Our smug conservative professor sees the revolution as “an expression of Russian barbarism”. (Figes, p.812) He cannot comprehend the idea of the working people taking power!

Again, Service adds his twopence worth: “Without Lenin, furthermore, Stalinism in the Soviet Union would have been impossible…” (Service, p.xix)

“Pity for Lenin the politician is hardly in order,” states Service. “He was a merciless polemicist, a ruthless terrorist and an unrepentant defender of practically everything done by him and his party.”

“On his death-bed he did not envisage a strategy of liquidating millions of innocent and hard-working peasants. Nor did he aim to exterminate his enemies, real and imaginary, in the party. But he did not fundamentally revise his attitude to horrors which he had perpetrated between 1917 and 1922.” (Service, p.322)

The theme of Richard Pipe’s work is clear: to portray Lenin as a psychopath, to whom ideas did not matter and whose main motivation was to dominate and to kill.

Figes urges his students to turn their backs on revolution and to learn the lessons of his masterly book!

“After a century dominated by the twin totalitarianisms of Communism and Fascism, one can only hope that this lesson has been learned,” says Figes. He goes on to warn: “The ghosts of 1917 have not been laid to rest.” (Figes, p.824)

World socialist revolution

We could write much more exposing the mountains of slander written about Lenin by an army of bourgeois historians, all keen to undermine his authority in whatever way they can.

We could write much more exposing the mountains of slander written about Lenin by an army of bourgeois historians, all keen to undermine his authority in whatever way they can.

Of course, the stock-in-trade of these ‘historians’ is to interpret history for their own ends. They hate the Russian Revolution, as with all revolutions, and display a particular venom towards Lenin and Bolshevism. So much for their ‘histories’.

It would take more than an article to answer all their lies and distortions. In fact, it would take several books. We therefore urge you, above all, to read Alan Woods’ book, Bolshevism; Ted Grant’s book, Russia, from Revolution to Counter-revolution; and Lenin and Trotsky, What They Really Stood For, which they co-authored.

The bourgeois historians – such as Service, Pipes, Figes, et al. – exist solely to slander Lenin and justify the continued enslavement of the working class. It is down to us to rescue these ideas and rescue the real Lenin. Leninism is the direct opposite to Stalinism, with all its crimes.

On the other hand, Lenin and his ideas represent a clean revolutionary banner that offers the workers and youth of today the road to the world socialist revolution. That is the message we must stress and remember on the 150th anniversary of the birth of this great man.