Central to the current crisis in Greece is the question of debt – particularly the national debt. Reducing public debt has became the main aim of (and reason for) the seemingly permanent austerity forced on the Greek working class. Fred Weston continues his series on the deep crisis of Greek capitalism by exploring the origins of the high debt levels in Greece.

Central to the current crisis in Greece is the question of debt – particularly the national debt. Reducing public debt has became the main aim of (and reason for) the seemingly permanent austerity forced on the Greek working class. Fred Weston continues his series on the deep crisis of Greek capitalism by exploring the origins of the high debt levels in Greece.

The Greek economy has always lagged behind the much more developed economies of countries like Britain, Germany, France and other advanced capitalist countries, mainly of northern Europe. The Greek bourgeois arrived late on the scene of history, with its own independent state only in the 1830s. Ever since, Greece has struggled to establish itself economically in the face of far more developed economies on the continent of Europe.

This weakness has been expressed in an almost permanent debt problem, with the country being in default for almost half of its history as an independent country. Greece has had major defaults on its sovereign debt at least five times, in 1826, 1843, 1860, 1894 and 1932. The last of these was during the Great Depression of the 1930s, which opened a long period of default which only actually ended in 1964.

This severe and long drawn out financial crisis explains why Greece moved towards revolution in that period, culminating in the Civil War, with the workers and peasants attempting to overthrow the landlords and capitalists. It also explains the big role played by the army in running the country, as there was little room for stable bourgeois democratic forms of government.

Post-war boom…

It was the post-war world boom that allowed Greece to achieve important economic growth, which in turn allowed it to end the state of decades long default. The 1950s was a decade of exceptional economic growth, with an annual average of over 6%, and in some years going above 10%. Industry grew at an even higher rate. This began a process of transformation of Greece from a strongly agricultural based society to an urbanised industrial society. The economy continued to grow through the 1960s and up to 1973 by an average of 8%. There was real growth, both in absolute terms and in terms of productivity. Thanks to this situation, between 1960 and 1973 Greece had budget surpluses, something it has never regained since.

Contributing elements to this long-term growth were the aid provided by the Marshall Plan after the Second World War, a severe devaluation of the drachma, foreign direct investment from other more developed economies into such industries as the chemical industry, as well as the development of tourism. There was also a massive construction boom, partially to rebuild after the damage of the Second World War and the Civil War, but mainly to cope with the massive flow of migrants from the countryside to the cities. There was another element, the Greek workers who had emigrated to America, Australia, Europe and other parts of the world, who sent back large sums in remittances, providing a boost to the local economy.

…and sudden slowdown post-1973

All this came to an abrupt end in 1973-74 when the world economy entered its first simultaneous worldwide crisis since the Second World War. All major economic crises bring out the real strengths and weaknesses of each national economy. Although Greece had experienced significant growth in the period 1950-73, it still remained far behind the more powerful economies of Europe. The productivity gap, which had been narrowing now started to widen again, and ever since 1973 the situation has worsened further.

If one looks at the period 1950-2007, it can be divided into more or less three periods, 1950-73 of very rapid growth, 1974-93 of stagnation, and 1994-2007 of renewed growth. This is more or less in line with developments on a world scale. There was the particularly critical period of 1980-1993 when the Greek economy almost stood still growing by an average of only 0.7% per year.

The question, however, is how the growth of the 1994-2007 period was achieved. And this is where Greece’s entry first into the EU in 1981 and then into the euro in 2002, brings out even further the fundamental weaknesses of the Greek economy. And it is also the period in which we see a massive expansion of debt at all levels.

The weaknesses of the Greek economy can be seen when one compares per capita GDP growth in Greece to that in the rest of Europe. In 1960 it was about 60% of the average European per capita GDP. By the early 1970s, on the back of significant real growth in the economy, it was catching up and had risen to about 80%, but by the late 1980s it had slipped back to what it was in the 1950s at less than 60%.

From the 1980s onwards the Greek economy began to fall further and further behind its competitors. Productivity growth slowed significantly after the 1973-74 crisis. Since then, Greece has undergone what some have referred to as a secular productivity slowdown, and this was due to a significant fall in investment levels post-1973.

Public debt as stimulus to growth

In the period of stagnation, Greek governments attempted to stimulate growth by massively expanding public spending. Greek public debt as a percentage of GDP shot up from 25% in 1981 to almost 100% in 1992. This eventually did produce economic growth, but it was driven mainly by increased consumption, much of which was based on increased credit and public spending.

There is also a historical element to the Greek public debt, which has similarities to countries like Italy. Due to the weakness of the Greek bourgeoisie, the state had always played an important role in terms of investment but also in providing a social buffer, i.e. literally buying social peace. Patronage and high levels of corruption also contributed to the accumulation of debt. Political parties, in particular New Democracy developed a system based on maintaining an electoral base via the creation of state jobs, state subsidies, and so on. Very often, getting a state job depended not so much on “what you knew, but on who you knew.”

There was a limit to how long and to what degree this system could continue to serve the interests of the Greek bourgeoisie. So long as the economy was booming, the underlying weaknesses could be papered over, but when the crisis broke out this was no longer possible. The problem was that to carry out the necessary cuts in spending also meant weakening the electoral base of the main Greek bourgeois party, namely the New Democracy. Local elites would resist any attempt to reduce patronage, and this meant the bourgeois did not have full control over the expansion of the debt. That explains, by the way, why at a certain point in the present Greek crisis – at the end of 2011 – a so-called “technocratic government” was imposed on the Greek people, led by the economist Papademos who had previously served as vice-president of the European Central Bank.

Entry into the EU

In the 1980s entry into the European Union also opened up channels for the funnelling of EU funds into the Greek economy and, especially after Greece’s entry into the euro, borrowing costs were massively reduced, as now Greece had access to interest rates which were far lower than they had been with the Drachma.

In the 1980s entry into the European Union also opened up channels for the funnelling of EU funds into the Greek economy and, especially after Greece’s entry into the euro, borrowing costs were massively reduced, as now Greece had access to interest rates which were far lower than they had been with the Drachma.

Prior to joining the euro, Greece was not considered as creditworthy as a Germany or a France. Yields on ten-year government bonds in Greece were at around 25% in 1993, while in Germany they were at about 7%. Once Greece became part of the euro zone its ten-year yields came into line with Germany’s and remained so until 2007. In this period, average annual economic growth in Greece at 3.9% was actually above the euro zone average of 2.2%. Being part of the euro gave investors confidence that Greek debt could be managed and, in case of problems, covered by the EU.

This was the period of growing living standards, with GDP per capita growing by 47% between 1996 and 2006. As the economy was growing, and growing seemingly well, the exponential growth in debt was considered manageable. What was not highlighted was a real decline in Greece’s ability to produce and to compete on the European markets.

After 2008 Greece suddenly became not as creditworthy as had been believed. Yields on state debt started to rise and then massively diverged from yields on German debt between 2010 and 2012. That year yields on German debt were actually falling to around 1-2%, while Greek yields rose to just under 35%! This is when the problem of the public debt became an urgent one to solve. It opened up a completely different period of deep depression, very different to the one that preceded it.

The role of Germany

The question, however, that has to be asked is: why did the major powers that dominate the EU, first among them Germany, allow such a huge debt to develop? Today they are all complaining about the “spendthrift Greeks”, who have been “living beyond their means”. But that is not the song they were all singing before this crisis erupted! In fact, they were all doing rather well out of the Greek situation.

Prior to entering the euro, Greek governments would use the mechanism of devaluation to gain a temporary competitive edge, but also to reduce the value of Greek drachma denominated debt in foreign currency terms. Once it joined the euro it was locked into a situation where it could no longer use devaluation as a means of alleviating moments of crisis.

There is also another very important element here, and that is that the expansion of the EU to more and more countries, and the introduction of the euro as the currency of many EU members, created a situation that was enormously advantageous to the German bankers and capitalists in particular. In fact the euro has been the mechanism by which German capital has strengthened its already dominant position in the European market. German industrial and finance capital had an interest in stimulating spending in Greece!

Unable to use the mechanism of devaluation, the weaker EU economies were unable to compete with the cheaper German goods and thus they started running up balance of trade deficits, i.e. importing more than they exported. Greece was particularly affected by this phenomenon. Ever since joining the EU, Greece’s balance of payments and balance of trade have steadily worsened. In the period 2000-2007 Greece’s annual trade deficit with Germany, for example, almost doubled.

German capitalists have held down wages in Germany and increased productivity significantly via investments. This has made their industries very competitive, but it has also limited the expansion of the home market. That means they must export. Germany has therefore opened up the markets of all EU member states, and particularly those that adhered to the euro. In Greece for a long period, there was growing consumption, as we have already seen, and this was in part driven by cheap credit.

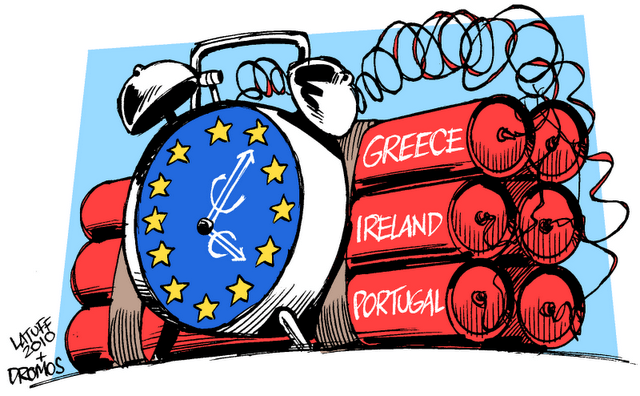

Who provided that credit? Mainly German banks! As a Reuters article from 2012 pointed out, “German lenders were among Europe’s most profligate before 2008, channelling the country’s savings to the European periphery in search of higher profits.” And, “Among European lenders, those in Germany are by far the most exposed to Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy…”

Greece’s ability to pay severely weakened

Thus we can see that the accumulation of Greek debt is not about Greek “mismanagement” of finances. It is about German, and other European, banks lending money to Greece and making a nice profit out of it, while the German companies also sold goods at a profit to Greece that was paying with German loans. This of course, could not go on forever. At some point the debt would become unmanageable. As Greece’s economic strength continued to decline, its ability to pay its debts weakened.

Thus we can see that the accumulation of Greek debt is not about Greek “mismanagement” of finances. It is about German, and other European, banks lending money to Greece and making a nice profit out of it, while the German companies also sold goods at a profit to Greece that was paying with German loans. This of course, could not go on forever. At some point the debt would become unmanageable. As Greece’s economic strength continued to decline, its ability to pay its debts weakened.

As the Centre for Economic and Policy Research pointed out, “The German position on the heavily indebted southern countries is absurd. It wants to maintain its huge trade surplus with these countries, while still insisting that they make good on their debts. This is like a store owner insisting that his customers keep buying more from him, while still paying off their debts. This is not just a question of southern Europeans being resentful or jealous, Germany is asking for something that is impossible.”

The only way for Greece to seriously begin paying off its debts, would be for it to massively increase its exports to the more advanced countries, Germany in particular, i.e. the customer would need to sell goods to the shopkeeper! The problem is the shopkeeper is not interested as he has his own goods to sell!

Greek debt has reached such levels – close to 180% of GDP according to the latest statistics – that it has become unpayable. All serious analysts understand this, but none of them are prepared to contemplate the consequences of simply letting Greece default, as this would have a knock-on effect, hitting those who hold Greek debt.

The only solution they have is to make the Greek workers pay, those who had no responsibility whatsoever in the build-up of the huge debt. There is, however, a limit to how much you can squeeze out of the Greek workers. Between 2010 and 2014 Greek wages were cut by about 20% and they have continued to fall since then. As we have seen in previous articles, this has had dramatic effects on living standards.

This explains the intense class struggle of the recent period and the extreme volatility on the political front. This volatility continues to this day, as we will see in the next few articles.

To be continued…