The event known as the ‘March Action’ of 1921 was a tragic chapter in the unfolding German revolution between 1918 and 1923.

This was a terrible and unnecessary defeat born out of an adventurous policy pursued by the young German Communist Party. It was a foolish and light-minded squandering of valuable human resources, at a time when they needed to be harnessed and educated for the tasks that faced the working class.

As with all important historic events – tragedies as well as victories – the March Action provides vital lessons for us today.

Revolution and counter-revolution

Germany had emerged from the First World War in the grip of revolution. The 1918 German Revolution had placed power into the hands of the German working class. But it was soon betrayed by its Social Democratic leaders. After this, Germany was convulsed by revolution and counter-revolution.

Germany had emerged from the First World War in the grip of revolution. The 1918 German Revolution had placed power into the hands of the German working class. But it was soon betrayed by its Social Democratic leaders. After this, Germany was convulsed by revolution and counter-revolution.

Following on from the successful October Revolution in Russia, the 1918 German Revolution shook European capitalism to its foundations. These revolutionary events in Germany were regarded as the harbinger to a potential socialist revolution throughout Europe. As a result, internationally, the bourgeoisie and their political representatives – including Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Wilson – were shaking in their boots.

The isolated workers’ state in Russia, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, looked for assistance from the workers in the West – especially Germany. Unfortunately, while the Russian October Revolution had a Marxist party at its head, the German Revolution lacked such a leadership.

In 1919, the Communist International was formed, with the view of establishing Communist parties everywhere that would seek to lead the working class to power.

In Germany, at the very end of 1918, a small Communist Party was formed. This was led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Leibknecht. Caught in the vice of the so-called Spartacist Uprising in January 1919, these key leaders were tragically murdered by the agents of the counter-revolution.

The young German Communist Party, due to its inexperience, made a number of serious mistakes and was prone to ultra-leftism. In particular, they adopted a sectarian attitude to participating in the trade unions, and they boycotted the elections to the National Assembly.

Furthermore, the party was born in a baptism of fire, as the forces of counter-revolution tore through Germany. Nevertheless, the embers of the revolution were still hot, and the working class was still intact.

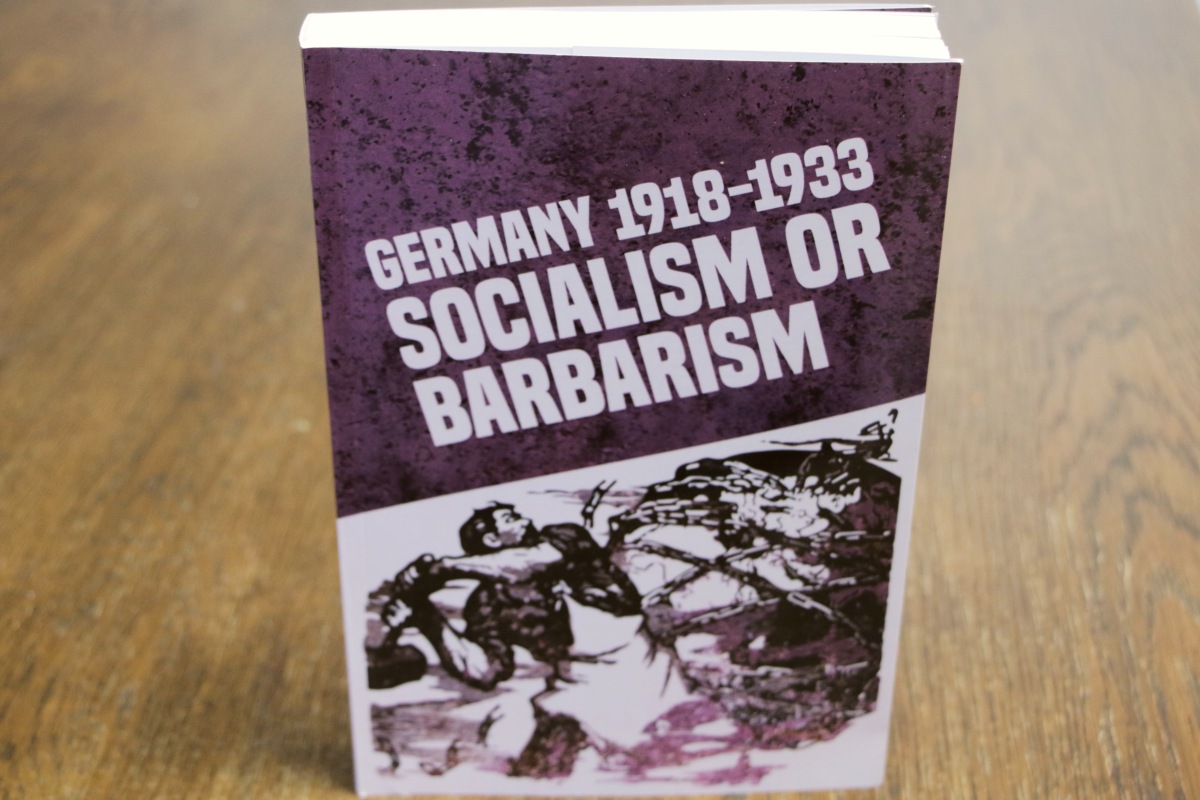

Rob Sewell is the author of Germany 1918-1933: Socialism or Barbarism, an important Marxist analysis of this historical period which draws out the lessons for revolutionaries today. This book is available from Wellred Books for only £14.99.

Ultra-leftism

Following the death of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, Paul Levi was elected the leader of the Communist Party. Levi tried to purge the party of its ultra-leftism.

By March 1920, the forces of ‘law and order’ attempted to establish a military dictatorship throughout Germany. This provoked a sharp reaction from the workers, and a general strike was called. As a result, the Kapp putsch collapsed. Following this, the working class had a further chance of taking power, but the trade union leaders acted to stabilise the situation.

The revolution sometimes needs the whip of the counterrevolution, explained Marx. This was certainly the case in Germany.

Apart from the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), there was another sizable party that had split from the SPD called the Independent Social Democrats. This party was deeply affected by the events of the period and moved in a centrist direction – from reformism towards the ideas of communism.

In December 1920, this party, which had around 800,000 members, voted to affiliate to the Communist International. It fused with the small German Communist Party to form the ‘United Communist Party’ (VKPD).

With such a mass following, the prospects for a successful German revolution were very promising, providing they didn’t make too many mistakes.

However, the leaders of the VKPD were very inexperienced and still susceptible to ultra-leftism. There were widespread illusions that the conquest of power would be straightforward.

This mood was fed by three emissaries from the Communist International: Bela Kun, Pogany, and Kleine, who were sent to Germany to assist the work. In Moscow, they were supported by Zinoviev and Bukharin, who adopted the so-called ‘theory of the offensive’. This idea was that the actions of the Communist Party could ‘spark’ the working class into revolutionary action.

Given the dangerous situation facing the young Soviet state, this theory gained support in the leadership of the German Communist Party. This became especially the case when Paul Levi resigned from the leadership, in protest at the way in which the Comintern had carried out a split in the Italian Socialist Party.

Adventure and fiasco

A critical situation was developing in Germany – especially in Saxony, where there was a civil war between the mineworkers at their employers. The SPD provincial governor, Otto Horsing, provocatively occupied the area with police, with a view of disarming the workers of weapons taken during the Kapp putsch.

The leaders of the CP regarded this as an opportunity to call a general strike and stage a revolutionary offensive. On 18 March 1921, Rote Fahne, organ of the party, appealed for resistance: “Every worker should defy the law and take arms where he can find them.”

But there had been no preparation; simply a call for action. In the circumstances, this was a complete adventure that could only end in a terrible defeat.

“This general situation urgently demanded from the German working class the snapping of the chains which bound them to the broken-down carriage of the bourgeoisie,” stated the CP leadership.

“It required the sharpest class struggles, it required the working class to seize the revolutionary initiative…and to summon its forces for independent action, to confront the counter-revolution with a powerful counter-attack…Whether passively to accept the counter-revolution’s decisions, or, acting in a revolutionary manner, to make its own decisions independently, and anticipate the counter-revolution by taking the initiative: this is how the question was posed for the German working class.”

(Ben Fowkes, The German Left and the Weimar Republic, p,91)

The party ordered the use of “artificial methods”, such as blowing up a workers’ cooperative society headquarters in Halle and blaming it on the police. They announced a general strike in Saxony and Hamburg. But this proved a total failure.

Max Holz, expelled from the CP, led a band of 2,500 in a week-long campaign of looting, bank robberies, and the dynamiting of railway lines.

Despite the heroism shown by sections of workers, the whole episode was a fiasco, without any plan or direction. Workers were expected to heed the general strike call at the drop of a hat. As expected, the movement collapsed. And on 1 April, the CP leaders were forced to call off the action.

Consequences and criticisms

The consequences were enormous. The March Action disastrously undermined and isolated the Communist Party. In the end, more than 200,000 members, half of its membership, resigned or dropped out. If such a policy was continued, it would completely wreck the party from top to bottom.

Paul Levi, who had earlier abandoned the leadership, now issued a sharp criticism of the whole affair. For him, the March Action was an unmitigated disaster.

While this was certainly correct, instead of taking the matter up within the party, he issued a public criticism in a pamphlet called Unser Weg: wider den Putschismus (Our Path: Against Putschism). In this pamphlet he denounced the party leadership in the most bitter language. He described the action as “the greatest Bukuninist putsch in history so far”.

Levi wrote that this putschist policy went against the Leninist premise of proletarian revolution, namely: the growth of revolution nationally; splits in the ruling class and the bankruptcy of the government; and the vacillations within the middle classes.

The fault for this mess, Levi asserted, rested with the Moscow emissaries (“not people of top quality”) and the stupidity of the German leaders.

Brandler, who had taken over the leadership, supported it “by talking nonsense for which he deserved to be sent to the cellars of a mental health clinic for a cold-water cure”. Another leader, Eberlein, meanwhile, “had no place in a communist party” as he believed that “one could drive the workers into action with dynamite or beatings”.

For making his criticisms public, Levi was expelled from the party. He obviously knew this was going to happen. Unfortunately, he let his ego get in the way of a correct criticism.

When Lenin heard of what Levi was doing he wrote: “Now Comrade Levi wants to write a pamphlet, i.e., to deepen the contradiction! What is the use of all this? I am convinced that it is a big mistake.”

“Why not wait?”, Lenin continued. “The Congress opens here on 1st June. Why not have a private discussion here, before the Congress? Without public polemics, without withdrawals, without pamphlets on differences.”

But it was too late, Levi had published his pamphlet and had been expelled.

Lenin and Trotsky

Levi had lost his head, said Lenin. But compared to the rest, at least he had a head to lose. He thought Bela Kun was a fool, and by implication all those who supported him.

Levi had lost his head, said Lenin. But compared to the rest, at least he had a head to lose. He thought Bela Kun was a fool, and by implication all those who supported him.

The German leaders, however, drew the opposite conclusions from Levi. For them, the action was a great success. It was apparently a tremendous advance.

“The ‘March Action’ is the first step the VKPD has taken in leading the German working class towards the revolutionary offensive,” explained Thalheimer, another leader.

The March Action had other ramifications, especially within the Communist International. The ultra-lefts in the Comintern leadership rushed to support the German Lefts. Zinoviev sent a telegram: “The Communist International says to you: You acted rightly!”

Lenin had been distracted from events in Germany by events in Russia, including the introduction of the New Economic Policy and the Kronstadt uprising. In the meantime, Zinoviev and Bukharin had been busy pushing the revolutionary offensive.

Lenin fully realised the grave danger this represented and began to prepare a counter-offensive against the Lefts. He had to tread carefully so as to isolate some and win over others. He also wanted to give them some room to retreat. He approached Trotsky and then Kamenev for support, and formed a bloc against Zinoviev and Bukharin.

Trotsky later commented in a letter regarding Paul Levi that “the Central Committee of our own party, even before the opening of the (Third) Congress, had to correct certain leftist deviations in our own midst.”

The ultra-left deviation was not only present in the German party, but also in Austria, Italy and other sections, to one degree or another. The only way in which it could be resolved was a full discussion at an international congress. And such a congress was scheduled for June in Moscow, which was attended by 600 delegates.

It was at this international congress that Lenin and Trotsky came out on what they described as the ‘right wing’ of the congress.

The main political report was given by Trotsky, who explained that the first phase of revolutionary advance between 1917 and 1921 had come to an end. There was now a period of relative stability, in which the Communist Parties should prepare for the next period.

“The situation has become more complicated, but it remains favourable from a revolutionary point of view,” Trotsky explained. The world revolution had been delayed not by months, but possibly some years. This set the tone for the debate on the March Action.

The draft thesis on the March Action was introduced by the Russian delegation. It obviously led to a heated debate. The Lefts defended the German’s approach, saying there had been no harm to the party. In fact, it added to their prestige.

Lenin took the floor:

“Comrades!…If the Congress is not going to wage a vigorous offensive against such errors, against such ‘leftist’ stupidities, the whole movement is doomed…We Russians are already sick and tired of these leftist phrases.”

Trotsky then intervened. He started by praising the courage of the German party. However, he said it was not courage but the policy of the March Action that was at issue.

“It is our duty to say clearly and precisely to the German workers that we consider this philosophy of the offensive to be the greatest danger,” Trotsky commented. “And in its practical application to be the greatest political crime.”

Art of leadership

The main task was to learn the lesson from this setback and prepare for the future. Rather than a theory of the offensive, they needed to first of all win over the masses.

At the Third World Congress, wrote Trotsky, we told the young Communists:

“Comrades, we desire not only heroic struggle, we desire first of all victory. During the last few years, we have seen no few heroic struggles in Europe, especially in Germany. We have seen in Italy large-scale revolutionary struggles, a civil war with its unavoidable sacrifices. Of course, every struggle does not lead to victory. Defeats are inescapable. But these defeats must not come through the fault of our party. Yet we have seen many manifestations and methods of struggle which do not and cannot lead to victory, for they are dictated time and time again by revolutionary impatience and not by political sagacity.” (The First Five Years of the Comintern, vol.2, p.10)

It was time to drive these lessons home. The policy of the revolutionary party cannot be guided by impatience and an attempt to jump over the objective situation. They needed to act with a sense of proportion and revolutionary realism.

Will power and determination are vital ingredients, but cannot be separate from a clear-headed perspective and tactics. Above all, they must avoid adventurism. There are no shortcuts to revolution.

“Only a simpleton would reduce all of revolutionary strategy to an offence,” explained Trotsky.

The idea that there must always be advances and no retreats is completely unsound. This is what the art of leadership is about. You can imagine a general in a war who only knows the command to advance. They would be smashed. A bad leadership can wreck a situation, as we have seen so many times. As Trotsky later explained:

“In March 1921, the German Communist Party made the attempt to avail itself of the declining wave in order to overthrow the bourgeois state with a single blow. The guiding thought of the German Central Committee in this was to save the Soviet republic (the theory of socialism in one country had not yet been proclaimed at that time). But it turned out that the determination of the leadership and the dissatisfaction of the masses do not suffice for victory. There must obtain a number of other conditions, above all, a close bond between the leadership and the masses and the confidence of the latter in the leadership. This condition was lacking.

“The Third Congress of the Comintern was a milestone demarcating the first and second periods. It set down the fact that the resources of the communist parties, politically as well as organisationally, were not sufficient for the conquest of power. It advanced the slogan: ‘To the masses,” that is, to the conquest of power through a previous conquest of the masses, achieved on the basis of their daily life and struggle.” (The Third International After Lenin, p.87-88)

United Front

The turn away from putschism and towards mass work was vital. The socialist revolution cannot win without first of all winning the masses. This entailed the tactic of the United Front, which is summarised by the slogan: “March separately, but strike together!”

This involved patient work in the trade unions and the involvement in the day-to-day struggles of the working class. The task of a revolutionary leadership was to convince the mass of the working class of the need for a revolutionary policy as the only solution to its problems.

This could only be done by showing the workers in practice that the reformist leadership is not prepared to fight capitalism to the end. It cannot be done by simply denouncing the Social Democratic leadership as traitors, which would only alienate the socialist rank and file.

The workers’ eyes can best be opened by the tactic of the United Front – by putting forward a programme which will be acceptable to the reformist workers. These workers would then exert pressure on their leaders to accept a struggle on the agreed programme. If the reformist leadership accepted, then a struggle would be waged, in which the superiority of revolutionary ideas would be demonstrated in practice; if it refused, it would stand exposed.

The United Front did not mean abandoning your organisation or your programme. It did not mean an inability to criticise. It did not mean that the Communists should dissolve themselves. They would retain their independence. But it would mean a common struggle for certain ends. It would be unity in action.

Following the Third Congress, this United Front policy was taken up energetically by the German party, allowing them to make great advances. The tactics were explained in the following way:

“The fight for working class power can only be victoriously conducted as a mass struggle, a fight of the majority of the working class against the rule of the capitalist minority. The conquest of the majority of the proletariat for the struggle for communism is the most important task of the Communist Party.

“The greatest obstacle to the development of the united front is the influence of the reformist leaders of Social Democracy…Through their policy of civil peace with the bourgeoisie (coalitions, Arbeitsgemeinschaft with the bosses, national unity) they bind large parts of the proletariat to capitalist politics and prevent any serious struggle. Hence the fight for the united front is today to a considerable degree a fight to detach the masses from reformist tactics and leadership…

“In the course of the joint resistance by the workers to the offensive of capital, the tactics of the Communists will prove to be superior to those of the reformists…The united front tactic is not a manoeuvre to unmask the reformists. Rather the reverse: the unmasking of the reformists is the means to building a firmly united fighting front of the proletariat…

In every serious situation, the Communist Party must turn both to the masses and to the leaders of all proletarian organisations with the invitation to undertake a common struggle for the construction of the proletarian united front.” (Fowkes, p.123)

Revolutionary school

This whole period from 1917 to 1921 in Germany was characterised by revolution and counter-revolution. Meanwhile, the masses learned from these titanic experiences.

In the first flush of the revolution, the small revolutionary forces proved too inexperienced to take advantage of such favourable opportunities. The Communist International was a school to educate the Communist Parties for the revolutionary tasks that lay ahead. These experiences served to enriched the revolutionary vanguard.

Today, the world is faced once again with a deep crisis of the capitalist system. The events of 1921 hold important lessons for us today – as does the period 1917-1923 generally.

Revolutionary events are on the cards everywhere in the next period. The key task remains the building of a leadership that knows how to act when the time comes.