Theresa May shocked the country this week by announcing a snap general election on 8th June. This is a fight that Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party can win, provided they offer a bold, socialist alternative. The meteoric rise of far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon across the Channel provides valuable lessons on how to fight this campaign.

Theresa May shocked the country this week by announcing a snap general election on 8th June. Despite the naysayers, this is a fight that Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour Party can win, provided they offer a bold, socialist alternative to grinding austerity. The meteoric rise of far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon across the Channel offers some crucial pointers on how to forge a radical movement for change that will boot the Tories out of Downing Street.

Mrs May’s U-turn (the Tories previously ruled out a snap election this year) is a sign of weakness rather than strength. Wedded to a ‘hard’ Brexit, and facing the possibility of a second Scottish independence referendum, May could well oversee, not only an economically calamitous exit from the single market, but the break-up of the Union. Despite riding high in the polls, she must shore up her position in advance of the political storm that will ensue as negotiations with the EU escalate.

On top of that, the Tories’ slim majority of 17 seats, a police investigation over electoral fraud, and the uncomfortable fact that May herself has never won an election, has put the Prime Minister on very shaky ground. Therefore, May will ask the British people to “put their trust” in her (at a time when the official opposition are torn apart by in-fighting), and ratify her hard Brexit, anti-migrant, pro-capitalist, anti-worker agenda of cuts and austerity with an increased majority. In short, she hopes to carry out Brexit on the Tories’ terms and secure their grip over the country in one fell swoop.

Of course, Brexit was itself a (politically confused) protest at the political establishment. It is precisely this establishment ‒ which has butchered the NHS and driven down real wages in Britain by 10 per cent since 2007 ‒ that May and the Tories represent. Despite ceaseless sabotage from the right of the Labour Party and the press, Corbyn can still capitalise on the public’s hunger for something new and make May pay for her hubris.

In the past couple of years, we have seen huge social movements erupt behind radical left-wingers in Greece, Spain and the United States ‒ seemingly from nowhere ‒ based on this appetite for change. Most recently, a left-wing firebrand has rocketed from obscurity in the French presidential elections to within touching distance of establishment favourite, moderate candidate Emmanuel Macron, and far-right demagogue Marine Le Pen (polling 20% to Le Pen’s 24% and Macron’s 23%).

There is much that Corbyn can learn from Mélenchon’s campaign in the French elections, which has shaken up the race and inspired millions of young people in particular with an unashamedly socialist message (he is the top candidate amongst 18 to 24 year-olds). At the moment, Corbyn faces an uphill struggle, with Scotland likely beyond his reach and the right of the Labour Party sharpening their knives in anticipation of defeat, eager to finally complete their ‘soft coup’ and shunt the party far to the right.

If he hopes to survive this snap election, there are four tips from Mélenchon’s campaign of which Corbyn should take note…

1) Break with the status quo: fight on a radical, anti-austerity programme

A major factor in Mélenchon’s sudden rise in the polls is his clear and consistent rejection of the existing economic order, and unapologetically socialist proposals to deal with French social ills. The programme laid out in his 350-point manifesto, L’Avenir en commun (‘the common future’) is considerably to the left of anything John McDonnell has yet come up with. Policies include a monthly minimum wage of €1,300 (£1,125), 100% taxation for those earning more than €33,000 a month, the renegotiation of EU-imposed “economic liberalism” (i.e. austerity, partial employment and less favourable working conditions) and new measures to protect workers’ rights and “common property” such as air and water. He also wants to lower the working week from 35 to 32 hours, pull France out of NATO and (possibly) consult the French people on whether to remain in the EU.

A major factor in Mélenchon’s sudden rise in the polls is his clear and consistent rejection of the existing economic order, and unapologetically socialist proposals to deal with French social ills. The programme laid out in his 350-point manifesto, L’Avenir en commun (‘the common future’) is considerably to the left of anything John McDonnell has yet come up with. Policies include a monthly minimum wage of €1,300 (£1,125), 100% taxation for those earning more than €33,000 a month, the renegotiation of EU-imposed “economic liberalism” (i.e. austerity, partial employment and less favourable working conditions) and new measures to protect workers’ rights and “common property” such as air and water. He also wants to lower the working week from 35 to 32 hours, pull France out of NATO and (possibly) consult the French people on whether to remain in the EU.

These ideas have chimed with a broad layer of the French public who are fed up with the austerity measures imposed by François Hollande and the Socialist Party (to which Mélenchon belonged for years but has now abandoned). The French masses have been locked in bitter struggle with the government over the past several years, with ceaseless strikes and protests ‒ lately over the so-called El-Khomri law, which has drastically altered the French labour code in favour of the bosses. On top of that, the traditional mass parties have collapsed, with the incumbent Socialist Party’s official candidate Benoît Hamon currently languishing at 8% in the polls.

There is every evidence that the masses are ready to roll the dice on something new. Of course, Mélenchon doesn’t go far enough ‒ should he be elected there will be a vast flight of capital as the rich flee France to avoid the taxman. In reality, he should expropriate their wealth without compensation to fund his planned reforms. In spite of its limitations, his programme is still substantially more radical than the mainstream ‘left’ of French politics, and has captured the attention of millions with the possibility of a genuine, left-wing alternative to austerity. Moreover, Mélenchon’s gains at Le Pen’s expense amongst blue-collar workers demonstrate decisively that the best way to fight the far right is with a daring message from the left!

May’s announcement came after Corbyn’s team unleashed a ‘policy blitz’ (including a £10 per-hour minimum wage, free school dinners and wage increases for caregivers) that went down well with the public. Clearly, there is fertile ground for left-wing economic policies in Britain, but Corbyn needs to be a lot bolder. With the NHS facing an existential crisis, wages falling and the public sector under the cosh of austerity there is plenty of scope to champion the drastic economic reforms that have put Mélenchon on the map. These should cohere around a clear socialist message: against the rich, against the capitalists and for the working class.

2) If you have numbers, use them! Build momentum on the ground

Perhaps the defining feature of Mélenchon’s campaign has been his ability to mobilise huge rallies, far exceeding those of the 2012 presidential campaign. On March 18 (the anniversary of the Paris Commune) his rally in Paris drew 130,000 supporters to the place de la Bastille, and on April 9 assembled 70,000 in Marseille ‒ a traditional stronghold of the National Front. These massive gatherings have allowed Mélenchon to speak directly with his support-base, bypassing the slander and distortions of the bourgeois press.

Seeking immediate contact with the grassroots has proved similarly effective in the campaigns of Pablo Iglesias in Spain and Bernie Sanders in the United States ‒ not to mention (it must be said) populists of the right such as Donald Trump. This approach allows supporters to gain a sense of their own strength, and publicise campaigns via social media, where news travels quickly and far, particularly amongst young people. This can result in a rapid multiplying effect, wherein obscure or maverick political figures can potentially ride a crest of grassroots support without impediment from the mainstream media.

Indeed, Mélenchon has made effective use of the internet as an organisational tool, which he claims can accomplish “90% of the tasks that previously justified the existence of a party machine”. While there can be no replacement for physical meetings and manifestations (we have seen the limitations of ‘clicktivism’ in wavering engagement with Podemos’ ‘direct democracy’), social media platforms present a viable means for activists to circumvent capitalist organs.

Furthermore, Mélenchon’s campaign is not built on the resources and finances of a major party, but on the enthusiasm of tens of thousands of local and neighbourhood campaigning organisations, mobilised under the banner of “Rebellious France”. By allowing the grassroots to take the lead in this way, Mélenchon has fostered a social movement that has struck a cold chill into the heart of the international capitalist establishment, with the Economist fearfully contemplating the “nightmare option” of a Mélenchon-Le Pen run-off.

Meanwhile, Corbyn’s election to the leadership of the Labour Party has swelled the party ranks to nearly half-a-million members. Despite mass disenfranchisement and expulsions of left-wingers by the Labour bureaucracy (not to mention Jon Lansman’s coup in Momentum), Corbyn’s greatest strength still lies with the grassroots. Attempts at ‘unity’ with the wreckers in the PLP have met with abysmal failure: Corbyn’s best hope now is to translate the radical energy he inspired during his two successful leadership bids into a transformative social movement for change.

The hundreds-and-thousands of activists brought into the party must now be inspired with a bold, socialist programme that will bring them onto the streets in force. The Labour bureaucracy will do its utmost to keep the membership under its thumb and ostracise Corbynites at ward and CLP level, which is why Corbyn must go to the rank-and-file directly through a series of public rallies to mobilise supporters. It is also incumbent on local left activists and Momentum groups to organise these re-enthused activists into effective ground teams that will canvas confidently in their local communities for a Labour government, contesting power on a socialist programme.

3) Don’t be afraid of fighting talk

Much of Mélenchon’s initial surge of popularity can be attributed to his stellar performance in television debates, in which his witty patter with the crowd and fiery rhetoric (which drew comparisons to Hugo Chávez) helped him stand out from the pack. Corbyn will likely never be a firebrand on par with Mélenchon, but he similarly rose from obscurity based on his impressive performance in television hustings against more ‘mainstream’ (i.e. right-wing) Labour leadership candidates like Andy Burnham and Liz Kendall, as his earnest and impassioned socialist ideas struck a chord with members. Unfortunately, he has shied away from public appearances in recent months ‒ seemingly terrified of saying anything that might upset the Blairite wing of the party.

Nevertheless, a strong speech at the 200,000-strong NHS rally in February showed that Corbyn can still address a crowd clearly and passionately about the key issues (with Tory privatisation of the NHS likely to be a key plank in his upcoming campaign), and this snap general election could be a golden opportunity for him to shine.

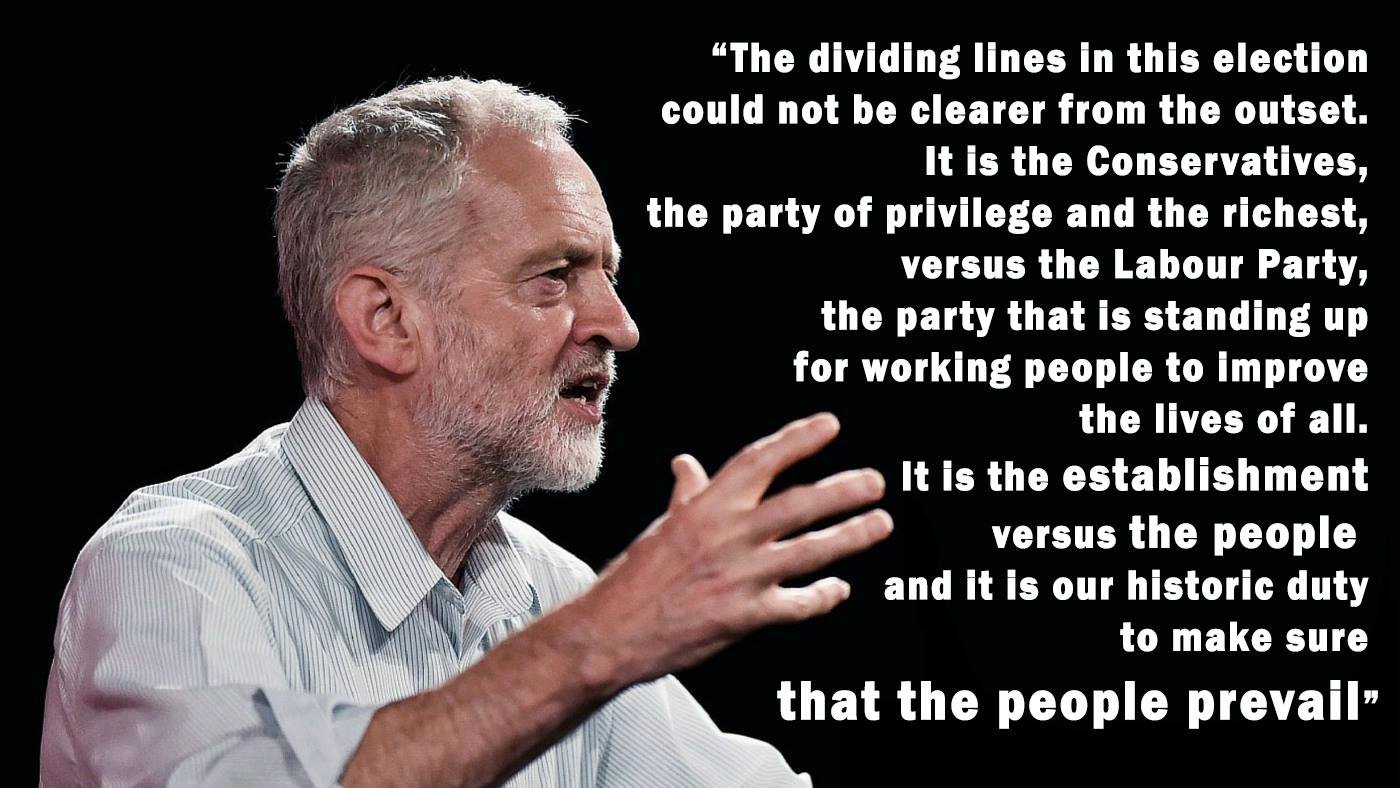

Corbyn has already shown promise in this regard, coming out fighting with his opening campaign speech, and describing this as an election that must be seen as “the establishment versus the people”. This establishment “do not want us to win”, the Labour leader correctly asserted, because when we win it is the people, not the powerful, who win.”

We don’t accept that it is natural for Britain to be governed by a ruling elite, the City and the tax-dodgers, and we don’t accept that the British people just have to take what they’re given, that they don’t deserve better

…the establishment and their followers in the media are quite right. I don’t play by their rules. And if a Labour government is elected on 8 June, then we won’t play by their rules either.

They are yesterday’s rules, set by failed political and corporate elites we should be consigning to the past.

It is these rules that have allowed a cosy cartel to rig the system in favour of a few powerful and wealthy individuals and corporations.

It is a rigged system set up by the wealth extractors, for the wealth extractors.

But things can, and they will, change.

This is the kind of bold, anti-establishment rhetoric that Corbyn needs to fight this election campaign with if he and Labour are to win.

Theresa May has already ruled out taking part in television debates, arrogantly implying she expects to win without having to defend her programme or record. Corbyn could easily capitalise on the opportunity to inspire the public with socialist policies while taking the Tories to task for their brutal treatment of the NHS and shambolic handling of Brexit.

Corbyn needs to continue with the combative tone that he has begun this campaign on, learning from Mélenchon’s, whose public speaking style is considerably sharper. His main campaign slogan, “degagisme” roughly translates as “kick them out” ‒ targeting the bankers, bosses and political elites who have sold the French people down the river. On top of that he calls for a “citizens’ revolution”, wants the constitution to be torn up and rewritten, and describes the “explosive situation” in France as “pre-revolutionary”. This fighting talk evokes Bernie Sanders’ appeal for a “revolution against the billionaire class”, which proved equally inspirational to a vast grassroots movement during the Democratic primaries in America.

Corbyn needs to adopt some of this fire. He has a matter of weeks to win over the public ‒ the time for kindness and gentleness is over. He must clearly state that the Tories are helping their capitalist cronies reap huge profits while the rest of us endure austerity. Therefore, the parasites’ wealth should be expropriated without delay under a democratic, socialist government that will fund the NHS, repair the education system, and house and employ the population on a decent wage. This is a message that could not only reinvigorate the thousands of supporters confused or impatient at Corbyn’s apparent inaction, but also win millions of ordinary voters to his cause ‒ particularly the huge population of non-voters, disgusted hitherto with the whole political situation.

4) Stand your ground and be optimistic

In the past several years, some of Corbyn’s high-profile ‘supporters’ have been almost as damaging as his critics. Owen Jones’ string of apocalyptic columns about Labour’s dire straits have had the effect of demoralising sections of his support base, while his appeals for ‘party unity’ have pressured Corbyn into the disastrous strategy of constant capitulation to the right of Labour. Meanwhile Jon Lansman’s decision to impose a new constitution on Momentum has robbed the organisation of its democratic structures and disempowered local groups.

In the past several years, some of Corbyn’s high-profile ‘supporters’ have been almost as damaging as his critics. Owen Jones’ string of apocalyptic columns about Labour’s dire straits have had the effect of demoralising sections of his support base, while his appeals for ‘party unity’ have pressured Corbyn into the disastrous strategy of constant capitulation to the right of Labour. Meanwhile Jon Lansman’s decision to impose a new constitution on Momentum has robbed the organisation of its democratic structures and disempowered local groups.

All of this has had the effect of confusing Corbyn’s message, undermining the left, and serving as a brake on the essential campaign to pursue mandatory reselection and deselection of rebel MPs to ensure the parliamentary party reflects the will of the membership. However, it must be said that Corbyn has not taken the fight to the wreckers in his own party. In an attempt to keep the peace, he has shifted his own programme to the right in some instances and zig-zagged in others ‒ such as on the questions of freedom of movement and Scottish independence. This has not been helped by constant attacks by the press, who have decried Corbyn as a friend to terrorists, an anti-Semite, a sexist, a dangerous radical ‒ everything but the unelectable kitchen sink.

Mélenchon has endured similar attacks, but seems to relish them. The French bourgeois paper Le Figaro dedicates a front page to attack Mélenchon with comparisons to Robespierre, Lenin, Trotsky and Fidel Castro (all fine company, if you ask me). Writing for the Guardian, Natalie Nougayrède levels a variety of bizarre accusations at the socialist candidate, whom she describes as anti-German and sympathetic to Vladimir Putin, and fraudulently misconstrues as bigoted to migrant workers (using an artful mis-quote from the British Socialist Workers’ Party, of all people!)

None of this defamation of Mélenchon has impacted his rhetoric, and indeed he continues to make frequent references to Robespierre, as well as the French socialist Jean Jaurès. Moreover, despite pressure from so-called left-wing commentators (including Owen Jones) to step down in favour of Hamon so as not to split the vote, he stood firm. Admittedly, he hasn’t had a mutinous party machine to contend with, but neither has he shied from his programme under attacks from the right.

Moreover, despite coming from an outsider position, Mélenchon exudes confidence in his ideas. Happily, rather than attempting to resist a general election race, Corbyn has met May’s challenge head on, saying that he is looking forward to “the opportunity to put [his] case to the public”. It is essential now that he stop wavering and inspire confidence amongst his supporters with an unflinchingly radical, socialist programme ‒ nothing less will do.