Trump is acting as a wrecking ball to the established world order. But his destructive impact is only possible because global structures have already been greatly weakened by the crisis of capitalism.

Expectations for the G7 were not high, but the outcome was even worse than expected. For the first time ever, the G7 ended without a joint statement, and with Trump lashing out at Canada and the EU. The summit in North Korea, on the other hand, ended with all smiles and a joint statement promising peace, denuclearisation and security.

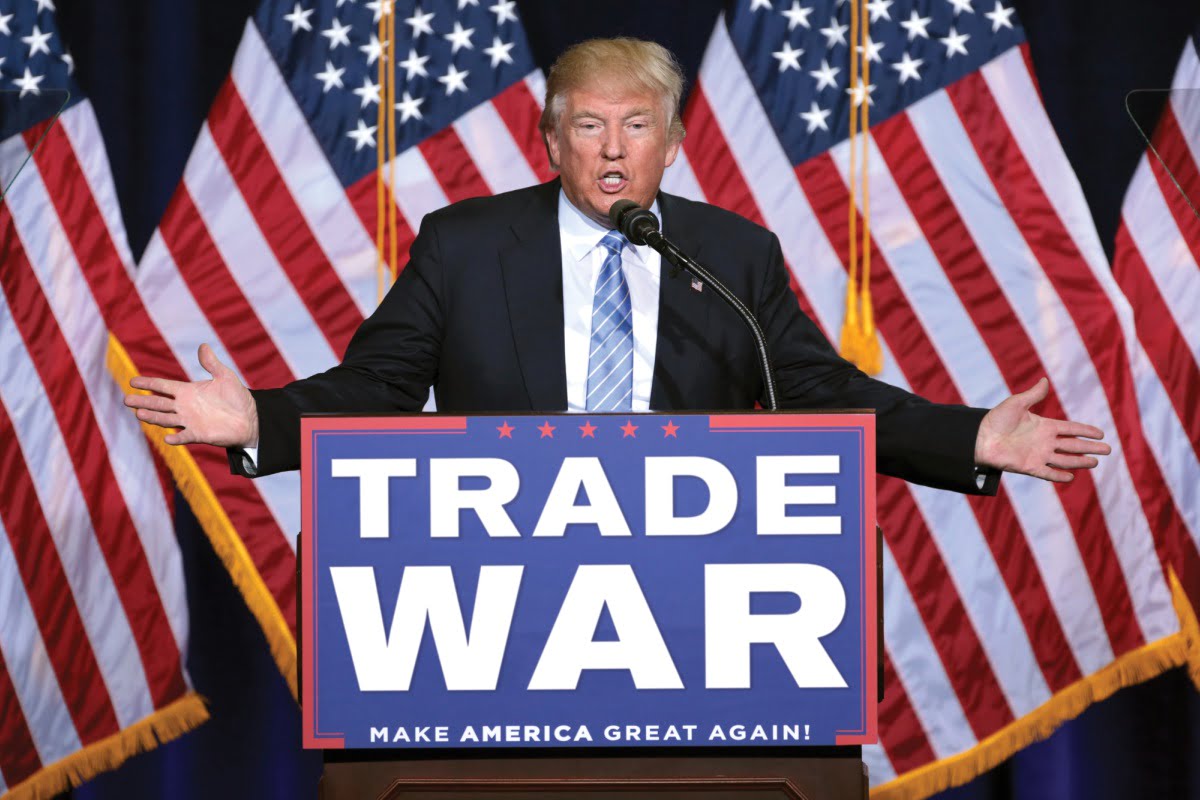

Who is robbing the US?

Trump had threatened not to attend the summit, and perhaps, in the end, the other participants may have wished he hadn’t. The summit was described as “cordial”, as opposed to the “friendly” atmosphere one might have expected from such a gathering of allies. Trump decided it was a good time to accuse his allies of “robbing” America.

Most likely this was part of Trump’s usual posturing: playing the hard man, and then hoping for a better deal when the dust settles – but such posturing has consequences.

One might ask, who is robbing whom? According to Trump’s logic, the US is actually robbing the Netherlands, Belgium and Australia, because the US has a trade surplus with those countries. A flow of goods, capital and services in one direction, inevitably mean a flow of money in the other direction. So, money is flowing into the US in the form of investment and loans, which is then used to pay for the goods and services that the US economy consumes from abroad. This way of describing trade relations is nonsense.

Trump also doesn’t bother too much with the facts when making statements. The US has a trade deficit with Canada when it comes to goods, but not when it comes to services; and combined, the US actually has a trade surplus with Canada. Figures for tariffs also show that the EU and Canada have pretty much the same tariffs as the US, on average, whatever might be the case on individual products.

This all goes to show that what is at stake here is not the US being hard-done-by, nor used by its allies, but that Trump is attempting to redefine trade relations to his allies’ detriment. He’s attempting to increase manufacturing production and employment in the US at the expense of the US’ main trading partners. In other words, he’s exporting unemployment and attempting to offload the social problems of the crisis onto his trading partners.

This is a more blatant and radical expression of what all the major powers have been doing for the past few years. The EU raised tariffs on some Chinese steel products to 73.7 percent. The Chinese in turn have a number of policies that basically subsidise their companies, something most Western countries have been doing for decades with agriculture. The list goes on.

In reality, free trade was always limited. Yet the past 70 years has seen a steady move towards liberalising trade, which is now being reversed.

Free trade imperialism

This January marked the 70th anniversary of the GATT coming into effect. The GATT was the predecessor to the WTO and was aimed at getting rid of the trade barriers that had been set up during the 1930s and 1940s. At that time, the US position was that trade surpluses weren’t a problem. The British (led by Maynard Keynes) were insisting that trade between countries ought to be balanced in the long run. Back then, of course, the US was running a large surplus (of around 10 percent of trade).

For the whole of the second half of the 20th century, the US played the role of pushing free trade, which was to the great benefit of US industry. The US emerged from the Second World War with the most efficient and competitive industries, and their industries had the most to gain from the opening up of world trade. It was a key, contributing factor to the post-war boom.

The US in this instance played the role that Britain had played in the 19th century: opening up new markets for world capitalism. At the time, of course, Britain was known as “the workshop of the world”, and out-produced any other country on the planet.

In order to be able to play this role, the US had to spend huge amounts of money on its military, defending what they called the “free world” against the Stalinist states, and anti-imperialist movements in the former colonial countries.

From the point of view of the development of industry in the US, this expenditure was a big burden, and something that other countries, in particular Germany and Japan, didn’t have to cope with. Instead they could spend that money on productive investments, making their industries more competitive than the US. The same goes for Trump’s criticism of US intervention in Iraq, where he thinks the oil contracts ought to be awarded to US companies since the US paid the bulk of the costs of the intervention.

In that sense, Germany and Japan have been piggy-backing on US imperialism, and Trump’s admonishments to its allies for increased military expenditure are not plucked out of thin air. On this point, Merkel and others have agreed to increase military expenditure even “if unpopular at home”, as the Wall Street Journal puts it.

There is a clear recognition that the US in this period cannot manage the joint affairs of Western Imperialism on its own; or alternatively, that the US cannot be relied upon to do so in the way that the German, French and British would like.

New tariffs

When it comes to trade, however, there is no agreement. Trump is attempting to strong-arm other countries into accepting less favourable terms of trade. In this, he is provoking the ire of his supposed allies.

When it comes to trade, however, there is no agreement. Trump is attempting to strong-arm other countries into accepting less favourable terms of trade. In this, he is provoking the ire of his supposed allies.

The US has for a long time relied on the EU to back it up in major international disputes, but now Trump has created a dispute with all his most important allies at the same time as he’s trying to force China to accept new terms. No wonder a large section of the US bourgeoisie are clutching their foreheads.

Now, Trump is threatening further tariffs on cars. This would be a whole different ball game. German exports of cars to the US are worth $22.8bn, $38.6bn for Japan (6 percent of total exports), $45.9bn for Canada (13 percent of total exports). This is in contrast to aluminium and steel, where the US imports are a fraction of the value.

It remains to be seen whether Trump will actually carry this out.

In the US Congress, the bourgeois are attempting to pressurise Trump. A new bill being introduced to Congress would force the president to seek Congressional approval before implementing new tariffs. Most likely, Trump will veto the bill, but a section of the ruling class is attempting to clip the president’s wings in the expectation, as the FT puts it, of “sanity” returning to the White House. So far, they haven’t had much success.

Trump’s supporters (and himself) defend his high-stakes negotiations by arguing that it gets results. Other than in Korea (both South and North), it is doubtful whether he has actually gotten any results. As the Wall Street Journal diplomatically puts it:

“The results so far haven’t been better trade deals, as Mr. Trump asserts. They’ve been rancor and the biggest threat to world commerce since World War II.”

The former colonial countries have often borne the brunt of the advanced countries’ tariffs, which has particularly affected products that they export. South Korea, Argentina and Brazil have already been forced to accept Trump’s trade terms. So, particularly for the smaller nations, Trump’s bully-boy tactics are having an effect.

“Rules based international order”

One of the sticking points during the G7 was a particular formulation on international trade based on rules and, by implication, multinational institutions.

One of the sticking points during the G7 was a particular formulation on international trade based on rules and, by implication, multinational institutions.

Although there was an agreement about the principle of free trade in general (whatever that means), Trump’s team opposed a formulation proposed by the Europeans supporting “the rules-based international order”. Instead the US wanted “a [!] rules-based international order”.

So, effectively the US delegation was declaring their lack of confidence in the existing international institutions.

In reality, Trump is opposed to multilateralism, and sees the US as having had a rough time in the UN, the WTO and NATO, as well as other multilateral trade deals, like NAFTA and TPP.

As a result, he is basically attempting to force renegotiation of all the major trade deals of the last 70 years, to the benefit of the US. Trump is at the moment paralysing the WTO’s dispute resolution procedures for next year by continuing to block the appointment of new judges and he has already abandoned NAFTA and TPP.

By exploiting a clause in the WTO agreement that allows for tariffs for the purposes of national security – for something that has little to do with national security – Trump is undermining the whole agreement. What is to stop the Europeans deciding that their cinema industry is a matter of national security and therefore put a tariff on Hollywood films?

The way that Trump conducts diplomacy completely undermines the whole basis on which these agreements are signed. Furthermore, it is done by the power that is meant to take the lead in enforcing the agreements.

The New York Times, being staunchly Democrat, carried headlines like “Trump Upends Trade Order Built by U.S.” and “Trump Tries to Destroy the West”. And, of course, they have a point.

Trump is attempting to upend the whole system that is known as globalisation. The ruling class internationally is attempting to salvage what it can of the institutions of international cooperation, particularly in regards to world trade.

In Britain, the Financial Times declared that “America has abdicated its responsibilities” and argued that the G6 (the G7 without the US) must “attempt to bypass Mr Trump by signing trade deals that exclude the US and keep the apparatus of global co-operation as functional as they can for when sanity hopefully returns to the White House”.

As an aside, this attitude of the White House towards its western allies is not doing the British any good. May and her Conservative Party were hoping for an easy trade deal with the US as a way to counteract Brexit. Trump has made clear that any such deal will have to be on US terms. This puts May and her government in an even more difficult position precisely when she is facing a Tory rebellion on Brexit.

A new period of turbulence

The crisis of 2008 has brought to the fore a number of contradictions in world relations that have been brewing for some time.

The crisis of 2008 has brought to the fore a number of contradictions in world relations that have been brewing for some time.

The US, although it remains the predominant world power, has become relatively weaker, and the same is true of the whole of the G7. In 1960, the US made up 40 percent of the world economy, while today it is only 23 percent. The EU has seen a similar development, where in 1980 the countries that presently make up the EU represented 34 percent of the world economy, whereas now they’re only 22 percent.

This relative weakening of the West is also reflected in international relations, which have been thrown into turbulence.

The social conditions in the US that led to the rise of Trump are a result of the crisis and the inability of the US ruling class to impose its will on society. Instead, its crudest representatives have been brought to the fore. Trump’s negotiating tactics might be suited to the gangsterism of real estate, but they are wreaking havoc in international relations.

This is a serious problem for the world bourgeois. Trump is threatening to send the world into a trade war unless his allies play to his tune. The director of the Carnegie Europe think tank put it like this:

“The trouble with trade wars… is that they sometimes happen even if no one quite starts wishing for one. If Trump responds to what will inevitably be a European counter response by doubling down—imposing more tariffs on Europe—what happens next?”

It is most likely that Trump and the rest of the G7 will patch up a deal for now. But how much damage will be done to the world economy first is a more interesting question, and it sets a dangerous precedent.

Trump has, in a sense, opened a Pandora’s box. The European ruling class will no longer be able to trust the Americans, and vice versa.

Free trade is a policy that the most competitive countries espouse as it facilitates them by providing a more open market. But those same countries who were free traders yesterday can very easily become protectionist tomorrow as they enter into decline and lose their competitive edge.

That is what we are witnessing before our eyes. And the worldwide economic slowdown is exacerbating the process. In a strongly expanding world market there is room for everyone. But when that markert ceases to expand it becomes clear that where one country wins, another loses. The loser will then seek other means – be they political, diplomatic or military – by which to protect or expand their share of the market.

The problem of course lies in the fact that when one power starts to impose protectionist measures, then it will merely spark tit-for-tat retaliation. The end result will be a strangling of the world market as a whole. That is what the serious bourgeois commentators fear.

For the working class, however, neither policy will serve to defend its interests, for neither can stop the inexorable crisis of the capitalist system.

What we are witnessing is the breakdown of the old order. In this context, the emergence of a Trump has a logic to it. It reflects the inability of the ruling class everywhere to manage its own system.