Two hundred years after its publication, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein continues to stand as one of the most enduring works of Romantic and Gothic literature.

What gives this work its enduring power? Shelley was a fantastic observer of man’s foibles, delusions, anxieties, and failings.

From her description of Victor Frankenstein; the supposedly brilliant, egotistical scientist who suddenly finds himself completely out of control of his own creation, to his monster, lonely, lashing out, and abandoned by its own creator – there is plenty here for modern audiences to admire.

Romanticism turned upside down

Mary Shelley was deeply influenced by the literary tradition of Romanticism. But she was also very critical of it. The Romantics were fundamentally individualists. They believed in the quest to, in the words of Wordsworth, “build social freedom on its only basis / The freedom of the individual mind”.

As a natural reaction to the oppressive development of capitalism, which turned workers into cogs in the machine, chained at the whim of the capitalist class, their philosophy had certain revolutionary implications – especially through the pens of its greatest writers, Byron and Percy Shelley.

The French Revolution struck them as all that they had wished for, with proclamations of liberty, equality and fraternity. But their utopian revolution quickly became a real one, subject to all the contradictions and internal struggles of a real social movement.

Most of these artists simply could not understand the necessity for Robespierre’s Terror. They reacted with fear and many moved towards conservatism. The Romantic movement splintered and struggled with the loss of its youthful innocence.

The literary heroes of the Romantic movement were bold, passionate individuals, unconstrained by social norms and rules. After the Revolution, these heroes became darker, more violent, and more destructive.

It is from this turn that we get some of literature’s greatest characters; The ‘Count of Monte-Cristo’, Mr Rochester, and Heathcliff.

Shelley’s writing, however, is different, going beyond the obsession with the individual. What all these other figures hold in common is that their egos make them strong, even if they are destructive. But Frankenstein has the opposite problem; his ego and self-obsession makes him weak.

Frankenstein himself is both the archetype of the Romantic hero and its opposite. He is ruled by his desires and impulses, narrating his inner turmoil in soaring, but hollow language.

Victor’s theoretical genius puts him at odds with the outside world. He thinks he knows so much, but is so self-obsessed that the limit of his knowledge is really the end of his own nose. For example, his attachment to Elizabeth is purely superficial, revealing not a deep bond but a projection of his own desires.

When he finally creates his monster, Victor responds with visceral disgust. This is the root of his tragedy. Because of his ego, Frankenstein cannot understand that the act of creation automatically involves creating something that you cannot directly control.

Victor “conquers death”, but then he is immediately confronted with life outside himself. Thus he rejects it and flees, abandoning his creation and beginning the cycle of events which will lead to tragedy, for him and many others.

Frankenstein’s monster

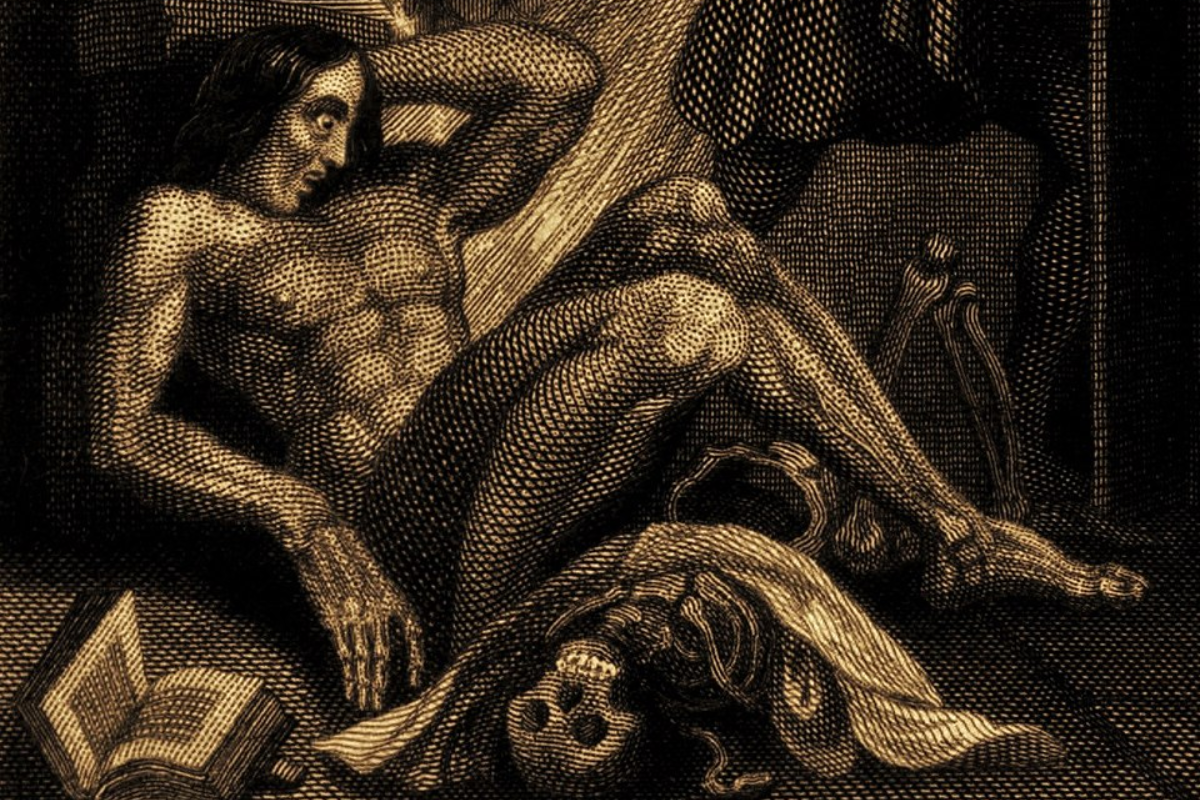

From its birth, the monster is despised and seen as grotesque by those who do not understand it.

Shelley describes how despite its confusion and isolation, the monster starts off trying to be “kind”, and to form connections with others. But, met with rejection after rejection, the creature eventually lashes out and embarks on a string of murders. It kills Frankenstein’s brother, best friend, and love interest over the course of the book.

And yet readers are drawn to sympathise with the creature.

The monster occupies a similar position to Milton’s Satan, or Shakespeare’s Caliban; thoughtful and creative beings that become violent because of the cruelty that they experience. Because their villainy is produced from terrible conditions, modern audiences sympathise with these characters in a way they never could with Prospero, or Frankenstein.

In many ways throughout the book the creature does prove itself to be more human than its creator, though it is not free of violence, nastiness, and the impulsiveness of its creator.

It realises at the end of the book that there is no real way forward for its existence, and it must be destroyed. Its creator, by contrast, never acknowledges his own responsibility.

Science and revolution

Shelley’s work is often seen as a critique of science itself: man’s arrogance in pushing beyond the limits and trying to “play god” results in a reckoning. This is an overly simplistic outlook, however.

In Frankenstein, science, like nature, is neither good nor bad, but powerful. These forces are much larger than the individual characters, who are regularly overwhelmed and frightened by nature (the storm when Frankenstein confronts his creature, the lightning strikes when the creature is created, and so on).

What Shelley critiques above all is the egos of the “great men of reason” who believe themselves to be able to control such great forces.

This is not to say that Shelley’s political cynicism doesn’t play a role here. Like with Shakespeare’s Caliban and Milton’s Satan, whenever the oppressed creature attempts to change its conditions it ends up making things worse.

Shelley’s criticism of the arrogance of man directly relates to her understanding of the French Revolution and the naivety of the Romantics. In Shelley’s mind, this revolution was a direct lesson about the dangers of carelessly messing with the established social order.

Later in her life, long after the publication of this book, she became even more conservative. Remarking of the 1848 revolutions, she said:

“Barbarism – countless uncivilized men, long concealed under the varnish of our social system, are breaking out with the force of a volcano and threatening order-law & peace. [. . .] In France how unscrupulous was the flattery that turned the heads of the working classes & produced the horrible revolt just put down.”

Shelley’s sentiment about the need to plan and think about all sides of a problem, rather than just heroically throw oneself in, were thus directed in an increasingly conservative direction.

This position is most bluntly exposed by the character of Walton, the explorer who quotes Romantic poetry, references the English Revolution, and ends up with his ship frozen in ice in the middle of a remote landscape.

Both Frankenstein and Walton recklessly throw themselves into improving the world through great new discoveries, only for it to lead to their doom. In the words of Victor Frankenstein to Walton:

“Unhappy man! Do you share my madness? Have you drank also of the intoxicating draught? Hear me, -let me reveal my tale, and you will dash the cup from your lips!”

Regardless of, and in a way due to her politics, Shelley’s great observational powers allowed her to smash through the barriers of literary convention, type and genre to create work that feels absent of stereotype and as alive today as it was when it was written.

Frankenstein defined many of the central themes of modern science-fiction and, as Del Toro’s excellent new adaptation shows, still has room to grow, be developed, and reinterpreted.

Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein’: A unique yet faithful adaption of Mary Shelley’s tale

Wyatt Morgen Holt, Cardiff

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is the closest interpretation of the original text we’ve seen yet. It is visually beautiful, and opts to drop the green monster trope.

He’s taken creative liberties, especially with Victor’s relationship with his family and with academia, which makes the story his own.

The use of captured butterfly imagery evokes the themes of transformation, unnatural evolution and attempts to recreate the beauty of nature. In contrast, the trademark Del Toro gore was intense, further exemplifying the haunting beauty of the film.

Del Toro adds his own political commentary through Henrich Harlander, an arms trader lining his pockets with the ongoing war, willing to bankroll Victor’s project so long as it benefits him.

The film also contains a deeper exploration of how the monster moves and looks, whilst also displaying the heart of the creature. He moves like a monkey yet speaks like a man by reciting Ozymandias.

There are clear allusions to the Prometheus myth, as the monster steals the gift of life and knowledge from Frankenstein, and is subsequently punished with a cruel and painful life.

The ideas Shelley was surrounded by are evoked throughout the entire film, which is summarised through the ending quote from Lord Bryon:

“And thus the heart will break. Yet brokenly live on.”

Alongside a limited cinema run, ‘Frankenstein’ is available on Netflix now.