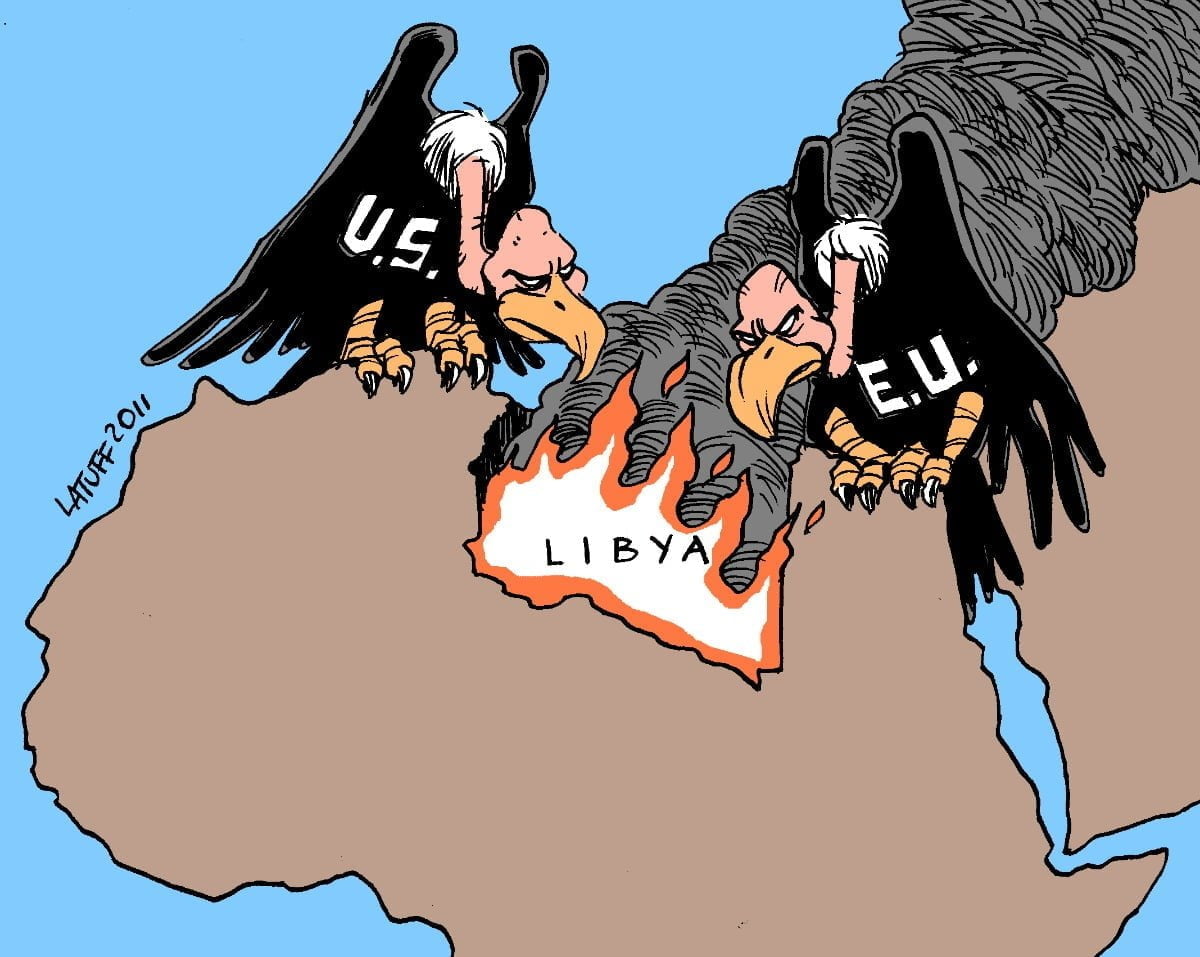

Five years ago, Muammar Gaddafi was caught and shot dead by the militias of the Libyan National Transitional Council, with the active support of the French Intelligence services. At the time, imperialist intervention in Libya was justified on “humanitarian” grounds. But what, in reality, have the imperialists achieved since?

Five years ago, on 20th October 2011, Muammar Gaddafi was caught and shot dead by the militias of the Libyan National Transitional Council, with the active support of the French Intelligence services. But what have the imperialists achieved?

The revolutionary events in Tunisia and in Egypt—the “Arab Spring”—had an effect in Libya as well. In Benghazi a popular insurrection erupted in February 2011 but was brutally crushed by the army. The force used by the Gaddafi regime in confronting the protesters led to a civil war, and the Western imperialists took advantage of the political vacuum left by the regime and intervened.

Although, the western powers had been doing good business with Gaddafi, they never fully trusted him because of his past behaviour over a period of decades. They therefore saw the civil war as an opportunity to remove him from power and intervene militarily to cut across the Arab revolution that had flared up in Tunisia and Egypt. It also provided powers such as France and Britain a chance to reassert themselves on the world stage.

With the death of Gaddafi, it was “mission accomplished”, as far as Western imperialism was concerned. However, the real situation today is completely the opposite. Libya is a country torn apart and divided, where no national government can claim to have a real control of the country and where local militias (including ISIS) have the power of life and death over the population of the areas they control.

The economy is in dire straits. Gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 10.2% in 2015, following a 24% collapse in 2014. In 2015, production of crude oil fell to the lowest level on record since the 1970s, to around 0.4 million barrels per day (bpd), which represents a quarter of the existing potential. (source: www.worldbank.org)

In spite of all this, in a recent interview with Al Jazeera, former NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen defended the air strikes on Libya, stating that “It was a very successful military intervention.” The only small problem, as he puts it is that “the UN did not follow up politically.” Paraphrasing the words of Tacitus, “They made a desert and called it peace… and they are proud of it!”

The words of Fogh Rasmussen reveal the cynicism of the ruling class. They are not interested in the plight of the common people or the suffering of the hundreds of thousands of women and children who had to abandon their homes and saw their families destroyed. The most important thing for them is that they have re-established their superiority and power over these “barbaric dictatorships” in the so-called third world countries.

Gaddafi’s role

We strongly condemned the imperialist intervention, and recent developments confirm that we were right. However, while condemning imperialist intervention in Libya, we do not join the chorus of the various post-Stalinists of various ilks who believe that under Gaddafi Libya was some kind of “land of milk and honey.”

Gaddafi took power in 1969. He was the leader of a coup d’état promoted by the Free Officers’ Movement, and was influenced by Pan-Arabism and Nasser’s Egypt. Their stance was clearly anti-imperialist, and when Gaddafi came into conflict with the Western powers, he took over the properties of Italian residents in the country and nationalised all the assets of British Petroleum. (for a full analysis, see: The nature of the Gaddafi regime – historical background notes)

Although he sought an alternative to imperialist domination, Gaddafi never went as far as the old Assad regime in Syria (where the colonial revolution was headed by a Pan-Arabic movement, as in Libya and Egypt), and capitalism was never actually abolished in Libya. What Gaddafi did was to attempt to modernise the country through the intervention of the state. Through the exploitation of the vast reserves of oil and raw materials – providing significant increases in living standards – he was able to build a large base of support among the masses throughout the 1970s and 1980s. However, private property relations were never questioned, and the capitalist (and feudal) structures in society remained substantially untouched.

At the same time, Communist ideology was ferociously repressed, and strikes and trade unions banned. There was no control from below, but only rule from the top, by one man alone.

Gaddafi ruled by balancing between the several tribes and feudal interests still present in the country. As long as the economy was growing, with tight control over the economy by the state, the system seemed to work. So it is true that Gaddafi was able for a period to unify the country, but he did it under a strict Bonapartist rule. Once the economy started to decline, repression and terror were the tools used by the regime to run Libya. As Napoleon once said, “You cannot rule by the sword alone.” Sooner or later, a questioning of the oppressive regime was inevitable.

After the collapse of Stalinism, when Gaddafi started to partially liberalise the economy, the different feudal interests and the problems of the historic division between Cyrenaica and Tripoli re-emerged.

In search of foreign investments and a market for Libya’s raw materials, Gaddafi toned down his conflict with the West, actively getting involved in the “war on terror” against Saddam Hussein, for example. However, in spite of all his efforts, for the US and the Western ruling classes Libya remained an unreliable partner. Thus, in 2011 when the regime began to crack, the imperialists seized the opportunity to remove it.

Imperialist interests

Imperialism used the National Transitional Council as their tool, but once Gaddafi had been toppled, the strategies of the local militias and of the different imperialist powers began to differentiate.

Imperialism used the National Transitional Council as their tool, but once Gaddafi had been toppled, the strategies of the local militias and of the different imperialist powers began to differentiate.

Libya, like Syria, become one of the battlefields between the different imperialist and regional powers. As in Syria, the conflict revealed firstly a changed balance of forces, and secondly the growing weakness of US power. Before the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Washington would have imposed its will quite easily on its allies (considered by the White House more as vassals). A Pax Americana would have been established—always, of course, at the expense of the living conditions of the masses.

Nowadays, the problem is that the vassals no longer follow the orders of their master. This is the reason why Obama considered the 2011 Western intervention in Libya the “worst mistake” ever made by his Administration. Since US public opinion has turned against the further deployment of ground troops abroad, especially after the failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US now has to rely on European governments, especially France and Britain. The West destroyed the old state apparatus in Libya, which later led to the breakup of the country. Al-Qaeda and its split-off, ISIS, did not exist before this. Western imperialism won the war but lost the peace.

What Obama did not take into account was that the different European (and Middle Eastern) governments all have their own agendas. Every national bourgeoisie struggles for markets and spheres of influence, and in Libya they play on the tribal rivalries which, during the period of Gaddafi’s rule, were temporarily balanced out.

Enter ISIS

Libya is in a strategic position, at the centre of North Africa, with its shores on the Mediterranean Sea, very close to Europe. Its oil reserves are huge: holding 38% of the African continent’s oil, and 11% of European consumption.

After the fall of Gaddafi, three main players emerged in the country. The government of Tripoli, supported by Qatar and Turkey, in the western part of Libya; the government of Tobruk, recognised by the so-called “international community,” sponsored by Egypt and the Arab Emirates; and the ISIS forces that controlled Derna, Sirte, and the surrounding areas. After the collapse of the old state and its unified army, several local militias emerged that formed tactical alliances with either Tripoli or Tobruk.

Alarmed by the growing influence of the Islamic State, the imperialists pushed for a national unity government against “terrorism.” Eventually, a “solution” was found—at least according to the propaganda of the mainstream media. A Government of National Agreement (GNA) was formed—sponsored, as usual, by the UN—and its Prime Minister, Fayez al-Sarraj, and several other ministers duly arrived by boat in Tripoli on March 30 of this year.

It soon became clear that not many of the Libyan militias had been informed of this “national” agreement. The reality was that al-Sarraj was able to enter the port of Tripoli only after several hours, waiting offshore, and only after the kind permission (and protection) granted, not by the UN’s blue berets, but by the local militias—those who have the real power in Libya.

Initially, Khalifa al-Ghwell, leader of the the Tripoli government, allowed al-Serraj to take office and retreated to Misrata, while the Tobruk Parliament, previously supported by the international community, never even voted in favour of the GNA. Four ministers from the East of the country boycotted the new government and never attended even one meeting.

Al-Serraj was a weak prime minister from the very first day. Living conditions for the masses worsened from the time he took office. “Tripoli had 20 hours of electricity a day, now it is 12… In April people had to pay 3.5 dinars for a dollar. Today it is 5 dinars.” (Tripoli Post, 13 September 2016). Inflation is soaring and the infrastructure is collapsing. No wonder that al-Serraj’s government is isolated; were it not for the support of the West, it would crumble very quickly.

Destabilised

Since August a new chapter in the civil war has opened. The US stepped up their involvement, with the bombing of Sirte. But the attacks, instead of stabilising the situation, have made it worse.

Under the framework of “Operation Odyssey Lightning,” the US Air Force launched 330 air strikes, with 150 just in the first three weeks of October. Every day the Western media have said that Sirte is about to fall, but al-Baghdadi militiamen are putting up fierce resistance. Agence France Presse on October 18 wrote that “550 GNA fighters have been killed and 3,000 wounded in the assault.”

As we have said many times, you cannot win a war, or even seize a city, with airstrikes alone. Sirte was Gaddafi’s hometown, and the dictator rebuilt it as the new Tripoli, with walls and towers, to protect it from a siege. To conquer it, you need to have boots on the ground. There is no national army in Libya, and no Western power is ready to send a sizeable military force to Libya.

That is why the US-led battle for Sirte, instead of strengthening al-Serraj, is weakening him. And in the meantime, other players are taking advantage of this weakness.

General Khalifa Haftar, the strongman of Tobruk, took control of the Sidra and Ras Lanuf oil terminals from the Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) led by Ibrahim Jadhran, a warlord loyal to the GNA government. Haftar is still actively supported by Egypt, and France looks to him with sympathy. French special forces are located in Cyrenaica, the region largely controlled by Tobruk.

While it is unlikely in the current situation that Haftar would be able to restart oil production – and, moreover, to sell it – the two refineries were vital for GNA income. Haftar now has a powerful weapon in his hands when it comes to future negotiations about the division of power within Libya.

In Tripoli, Khalifa al-Ghwell and the militias staged a coup and took over the Rixos Hotel, home of the government’s State Council Assembly. The UN condemned the coup and the GNA ordered the arrest of the plotters, but the militias are still holding the hotel.

For several days no one knew where al-Serraj was hiding. Finally, it was discovered that he was issuing orders from a “secret” location in Tunisia!

Socialism or barbarism

The Western powers and their proxies are re-positioning, taking for granted the fact that al-Serraj’s days are numbered. Naturally, they are increasing their presence in the region, with the usual justification of fighting ISIS terrorism.

France is one of the most active powers in this scenario. Last July, the GNA issued a protest where it “’considered the French presence in Libya’s eastern region as a breach of international norms and sovereignty.” (Libya Herald, 29 July 2016) France ignored that protest and increased its presence, a fact exposed by the crash of an airplane in Malta last Monday. At least three passengers were members of French intelligence heading for Libya.

Italy, the former colonial power, is trying not to be excluded from the division of the booty. In September they sent 300 soldiers to Libya, with “humanitarian” intentions, of course. The Italians are planning to build a military hospital in Misrata, and the official task of the troops will be “to protect the premises.” In reality they are going to protect their local proxies in Misrata and in the siege of Sirte. Not everybody is happy with the Italian initiative. The Zintani Brigade (a militia that, when it changed sides, was crucial in the fall of Gaddafi) declared that it would “not stand idly by and will face any invader with all our might,” and “we call on all Libyans to stay united and prepare to fight the new Italian invasion of our land.”

The situation in Libya is like a hornets’ nest, which they cannot destroy, and the more the imperialists try to put their heads inside, the more they will be bitten.

The civil war in Libya is assuming a long and protracted character. A likely perspective is a de facto partitioning of the country. This is a crime of imperialism, which consciously intervened to loot and plunder, without any consideration for the fate of ordinary Libyans.

This perspective could be reversed only by the rise of class struggle in the neighbouring countries. It is the task of the mighty Egyptian proletariat and of the Tunisians to overthrow their rotten governments and the capitalist system. Their victory could act as a beacon for the oppressed in Libya. A revolution across the Maghreb and in Mashrek would be a beacon to the Libyan masses who would see in it an example to follow and would thus find the strength to expel the imperialists and move against the semi-feudal warlords and militias.

Socialism or barbarism: this slogan was never so real, tragically, as it is in Libya today.