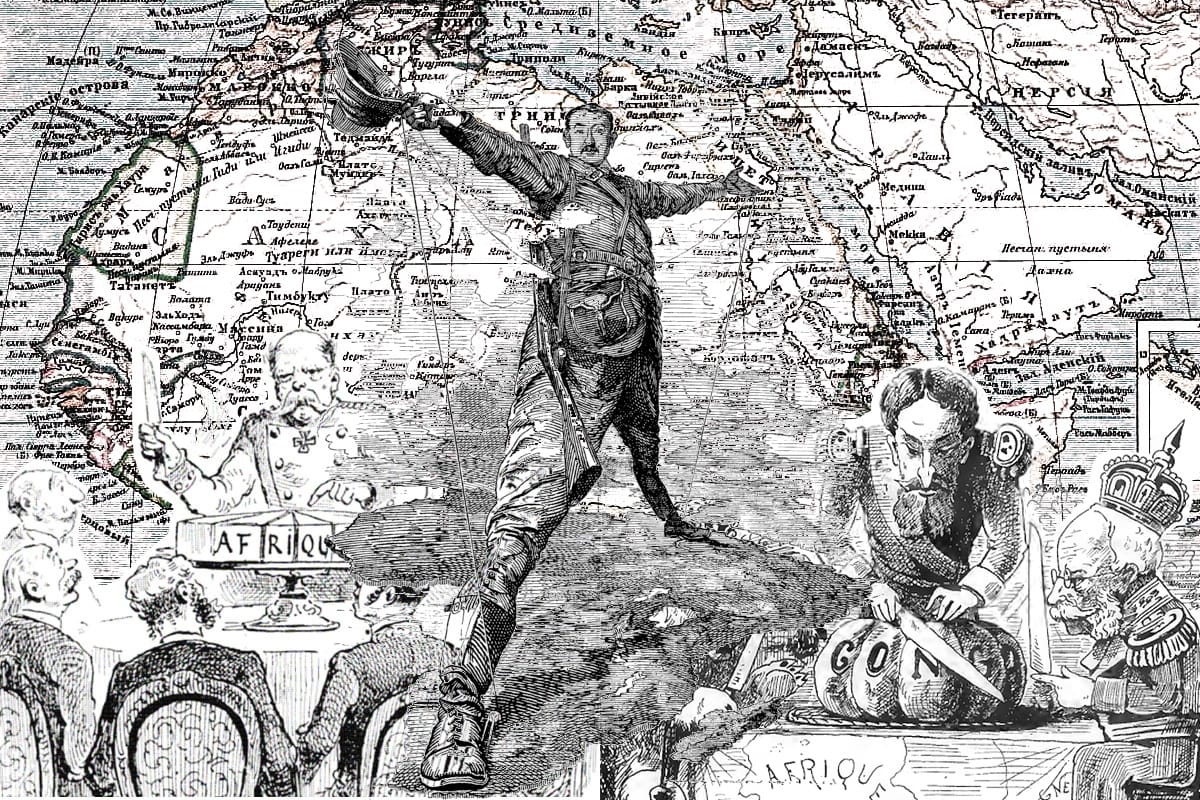

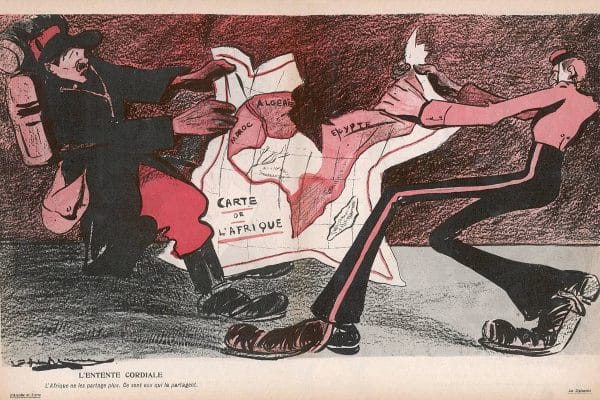

140 years ago today, the leaders of all the major capitalist powers assembled in Berlin to carve up Africa between themselves.

The Berlin Conference was a key event in the scramble for Africa, in which imperialist powers committed countless atrocities, in the name of ‘civilising’ the continent, and even abolishing slavery.

As the following article will explain, rather than being the start of the scramble, as some sources state, this conference merely formalised relations between the powers after over a decade of brutal colonisation – the effects of which are still felt today.

Leading the charge was British imperialism, which played by far the biggest and most brutal part in the subjugation of an entire continent.

This article is from the RCP’s brand new booklet, The Crimes of British Imperialism. To fight imperialism, we must scientifically understand what it is, and where it came from.

This booklet is therefore aimed at arming communists in the revolutionary struggles to come, to end the system which caused these heinous crimes.

Order your copy at Wellred Books Britain.

Voir cette publication sur Instagram

In 1870, European imperialism had only established a handful of colonies at the fringes of Africa. Yet by 1914 it had laid claim to the entirety of the African continent except for Ethiopia and Liberia, the latter an American colony that became independent in 1847.

The near entire subjugation of a continent by European imperialism was the culmination of a long process that began with the emergence of capitalism in Europe.

From the voyage of Vasco de Gama around the African coast, to the establishment of the transatlantic slave trade, to the first colonies in the Cape of Africa, at Lagos, in Angola etc., the needs of capital had introduced a predatory relationship between Europe and Africa.

False theories

The direct conquest and enslavement of a continent was however, a clear qualitative transformation in this centuries long predatory relationship. There are all sorts of weird and wonderful theories that explain how and why this transformation took place.

The justifications given by the colonisers themselves were based on a racist view of history, that whites had an inherent superiority over their African subjects. Within this existed two different approaches.

One strand argued that Africans were so savage that they weren’t really human, and so they were just so much raw material for exploitation, and Europeans had to assert their rights to land.

This attitude was the one expressed by Cecil John Rhodes who played a significant role in Britain’s colonisation of modern day Zimbabwe and Zambia.

The other side of the racist coin was the view that it was the duty of whites to civilise the ‘savage’ Africans and so they had to intervene and rule over them. This was espoused by Frederick John Lugard who was colonial governor of what is today Nigeria.

Whilst officially these racist explanations are no longer accepted by the bourgeoisie, every now and then the mask slips, and we see their real thinking.

In 2002, Boris Johnson would write about European rule in Africa: “The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more”.

His disgusting article contains all the old tropes about Africans being incapable of making use of their land, and how it was colonists who had to plant the ‘right’ crops.

These ideas continue to exist amongst the ruling class because, in truth, the racist contempt they hold for Africans is not a far cry from their attitude towards the poor and dispossessed in their own country.

Ultimately they view both as inherently inferior and incapable of being ‘useful’ without the rule and direction of brilliant men like Boris Johnson, Sir Keir Starmer, etc.

It is true, however, that other theories and explanations are now more commonly propagated by the ruling class through its universities and schools.

Much of this seems to take the colonisers at their own word, putting the cart before the horse by saying that European racism led Europeans to colonise Africa.

Rather than understanding racism as being a product of and justification for colonialism, it is argued that such ideas caused this phenomena.

This isn’t to say that Europeans didn’t earnestly hold racist views, but that racist attitudes cannot explain why suddenly an entire continent was brutally subjugated.

The dawn of imperialism

Focusing on racist attitudes serves to obscure the truth, that the brutal colonisation of Africa flowed out of the objective requirements of the capitalist system.

The truth is that what was really transformed in 1870 wasn’t European attitudes, or how international politics was conducted. What transformed was the nature of the capitalist system itself.

The powerful development of the productive forces that had taken place from 1850 onwards had thrown up new contradictions. No sooner had the bourgeoisie established the main national markets that the industry they built outgrew them.

The capitalist industry of Britain, France, Germany, and even smaller countries like Belgium, was capable of producing far more than the home market could absorb.

There existed surplus capital, and the ruling class was all too acutely aware that idle capital is no capital at all. If it couldn’t be profitably invested in the home market, new markets would have to be established.

What took place between 1870 and 1914 was the transformation of capitalism into imperialism in the modern sense. This was the era of the rise of the monopolies; the era of finance capital’s domination over industrial capital; the era of the former’s complete dominance over the state.

How could Europe conquer Africa

It is this that chiefly explains why Europeans wanted to colonise Africa. They sought out the resources of the continent, looking to plunder the rich natural resources to furnish industry at home.

They looked to also establish vast captive markets for these commodities, as the products of the home market held exclusive sway in the respective colony.

The development of capitalism in Europe first gave European nations more advanced technology and productive capacity than the rest of the globe. This is what allowed European capital to subjugate most of the rest of the world.

Africa itself was particularly vulnerable to the development of imperialism because it was amongst the most economically backwards parts of the globe.

Some of this owed to deeply unfavourable environmental factors that held back population growth and undermined agricultural production.

Far more devastating was the way in which Africa was incorporated into the emerging world market from the 15th century onwards; namely through the export of slaves.

The slave trade emerged because Europe’s subjugation of the Americas had been so brutal that around 90 percent of the population were wiped out within three generations.

To make the colonies profitable, the European bourgeoisie turned to African slaves, beginning a centuries-long devastation of the African continent.

The impact was catastrophic, as areas like modern day Angola were decimated from the extraction of people. Domestic industries were dismantled as the elites of African polities turned to the more profitable trade of slaves.

Wars abounded as Europeans cynically sold weapons to those who sold them slaves, encouraging aggressive wars of expansion to fuel the slave trade.

The slave trade completely retarded the development of Africa, leaving it extremely vulnerable to European imperialism in the late 19th century.

Britain’s role

In the era of the ‘Scramble for Africa’ Britain was the leading imperialist power, having stolen a march in the development of capitalist industry.

It was for this reason that by 1914, Britain ruled over 30 percent of the continent’s population, twice the number of the French colonial holdings; the second largest in Africa.

Britain came into possession of the Cape colony, in what is today South Africa, in 1795, seizing it from the Dutch as French revolutionary troops had brought about the Batavian Republic in Holland.

Meanwhile British colonisation of India furnished British capital with an immense pool of cheap labour. On top of this, Napoleon, British capitalism’s mortal enemy, was re-establishing slavery in France’s colonies like Guadeloupe.

All of this compelled them to conclude that the slave trade, that had laid the basis for British capitalism, had now become a fetter to its continued domination. It was for this reason that Britain banned the slave trade.

They also recognised that banning it provided an excellent excuse for establishing direct control of territory in Africa. The following year, in 1808, they established the colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa with the slaves freed by Royal Navy ships.

Such a model laid the basis for the American colony of Liberia established in 1822. Britain’s supposed ‘humanitarian’ mission gave it the perfect excuse to increase its colonial presence on the African continent.

Indeed, this was one of the prominent justifications made by all European powers in their scramble for Africa, that they were ‘putting an end to slavery.’

Under this pretext, Britain would seize more territory in West Africa over the course of the 19th century, once again stealing a march on its competitors.

In 1861, for example, Britain intervened against the Yoruba, who were waging aggressive wars for the purpose of capturing slaves, and established the Lagos colony that year.

Cecil John Rhodes

By 1870, only Portugal had matched Britain’s conquests on the African continent. Whilst the state supported the colonisation of Africa, particularly with the armed bodies of men it sent to put down resistance, the process was at all times driven by capitalists and their corporations.

Cecil John Rhodes was the archetype for this process. He entered the Cape Parliament in 1881, building political connections with the colonial state before founding the De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888 to exploit the vast diamond wealth in the colony.

Two years later, this powerful mining magnate became the Prime Minister of the Cape, a position he used to further his business interests. Big business was completely entwined with the state in the colonies to an even higher degree than back home.

In what would become South Africa, the colonial state was established along the same lines as the bourgeois state in the imperialist country.

The bourgeoisie of the colonies didn’t have to capture the state machinery from another class, as in Europe, or contend with a slavocracy as in America. It built the state in the colonies, creating the perfect machine for defending and furthering the interests of capital.

The distinction between the bourgeoisie and their colonial administration was negligible. Consequently, as Prime Minister, Rhodes was able to pass laws that dispossessed Africans of their land so that they’d be compelled to sell their labour power.

Rhodes stated: “It must be brought home to them that in future nine-tenths of them will have to spend their lives in manual labour, and the sooner that is brought home to them the better.”

Violent origins of capitalism in Africa

In 1894, the Rhodes government passed the Glen Gray Act, which converted communal lands into private property and imposed a tax on Xhosa men so they’d be compelled to sell their labour power to earn a wage.

He was also an early proponent of the law that would be passed in 1913, the Native Lands Act, that reduced the area of South Africa that Africans could live in into less than 10 percent.

This land was the most marginal, and the most difficult to produce crops on. Again, the idea was to compel black Africans to sell their labour power to capitalists like Rhodes.

Today the idea of selling our capacity to labour to a capitalist appears as natural and inevitable as the movement of the tides.

This was not always the case, however. The bourgeoisie had to inflict violence to turn people into ‘free workers’ – i.e. people no longer tied to the land, who owned nothing but their capacity to labour.

The brutal creation of the ‘free worker’ had taken centuries in Europe; it took place in just a few decades across Africa.

It was a process that involved brutal violence directed against Africans, depriving them of their means to survive independently so they could be exploited by the British capital.

Kenya, like South Africa, was a settler colony that Britain founded with the view to it being a preserve for British colonists who would exploit indigenous labour. In 1905, Colonel Hennessey used a Maxim machine gun to slaughter 1,850 men, women, and children of the Kipisigi people.

The colonial administration wanted to drive the Kipsigis from their ancestral homeland because it was stated that the “well-watered white Highlands were fit to raise a European child.”

The British also expelled 100,000 Talai people to Gwasi, which was known to be unfit for human habitation, leading to thousands of deaths.

All of this secured farmland to white settlers and gave these same capitalist farmers a pool of cheap African labour to exploit. The history of colonial rule in Africa is littered with such massacres in the interests of capital.

In the period from 1890-1920 the populations of Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda declined by 14 percent, 15 percent, and 10 percent respectively, as a result of British brutality.

Britain was at the forefront of bringing capitalism to Africa with all the violence, misery and degradation this entailed.

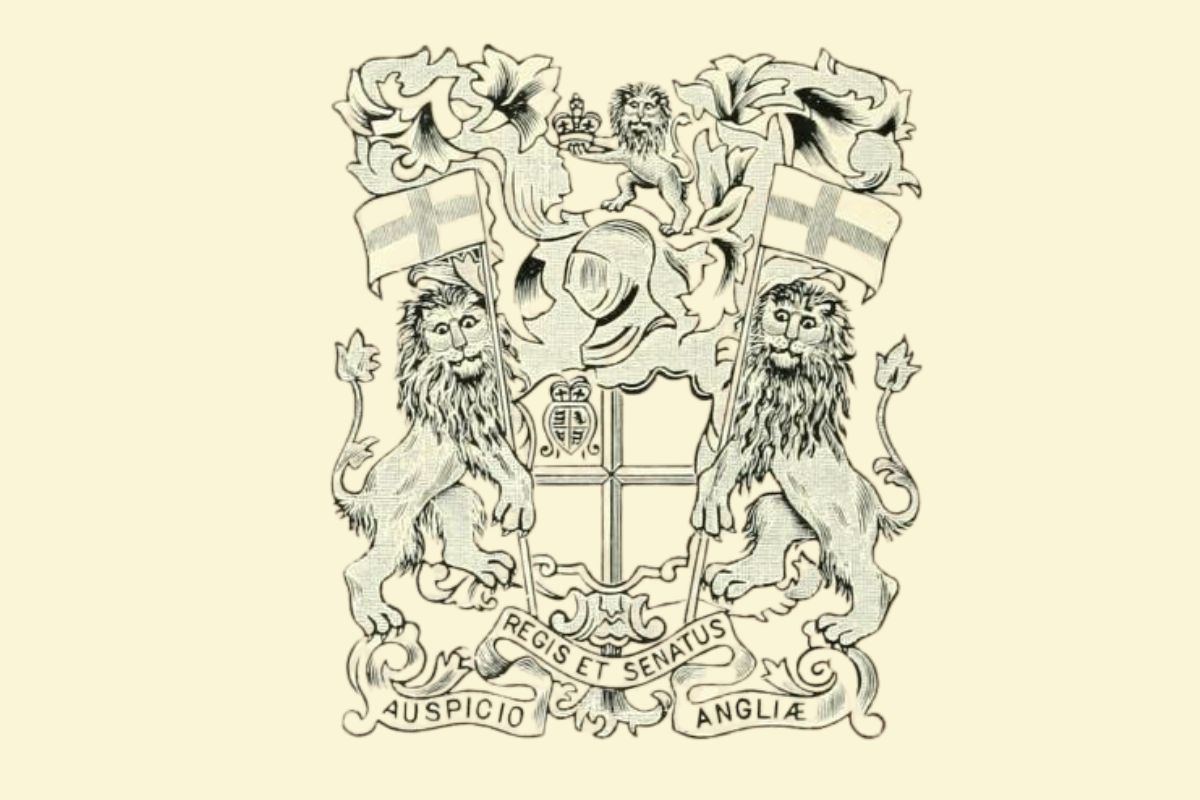

Yet what really made Rhodes the archetype of British colonialism were the actions he took beyond South Africa. In 1889 he founded the British South African Company (BSAC) for the sole purpose of acquiring land north of the Limpopo River.

Its modus operandi was to send respectable bourgeois gentlemen to negotiate mining concessions with local elites like Lobengula, King of the Ndebele in Matabeleland.

These bourgeois negotiators would bring agreements codified in bourgeois legal jargon, completely alien to men like Lobengula, and containing sinister terms that justified the complete colonisation of their territory.

For instance, the infamous Rudd concession, named after Charles Rudd, stated that mining companies could take any action to guarantee their interests, whilst verbally Rudd assured Lobengula that no more than ten white men would come to mine the territory.

Lobengula had thus ‘legally’ signed away his territory to the BSAC. This was acknowledged by the British state, who then gave the go-ahead for the company to move in.

In the wake of the negotiators came the Pioneers Column, hundreds of armed colonists enlisted by the BSAC to put down resistance to colonisation.

These ‘pioneers’ formed the nucleus of the paramilitary force of the BSAC that would successfully subdue the armed uprising of the Ndbele, led by Lobengula, in the First Matabele War of 1893-4.

These methods would be deployed across Southern-Central Africa so that the modern day territories of Zimbabwe and Zambia would be directly owned by BSAC. Both colonies would be named after their chief architect, becoming North (Zambia) and South (Zimbabwe) Rhodesia.

Eventually the British state would assume direct colonial rule in the 1920s, not to protect the indigenous from the brutal exploitation they were subject to, but to reinforce the forces of repression keeping them pliant.

The myth of modernisation

Apologists of British colonialism in Africa claim that whilst British rule may have been cruel, at least it was modernising, that British rule was a force for development and progress. This is completely false.

Whilst it is true that British rule built ports and laid railways, this infrastructure served as a means of draining its colonies of raw materials.

Contrary to colonial claims, British rule actually strengthened the most backwards and reactionary elements of African societies.

Frederick Lugard, the colonial governor of Nigeria, was the archetypal example of this. His administration of the colony rested upon traditional tribal elites and kings, particularly in the North.

For instance, when the British conquered the Caliphate of Sokoto, Lugard used the conquered Emirs to administer the territory. Lugard even permitted these elites to keep slaves in return for their help in controlling the population and directing them towards avenues profitable for British capital. Meanwhile he claimed his mission was to abolish slavery!

Lugard favoured the North precisely because it was the most backward. There was no domestic industry that needed uprooting as there was in the South.

This was the raison d’être of British imperialism: it propped up the most rotten and decayed elements of the societies it dominated in order to allow for the untrammelled domination of British capital.

Kings and chieftains could be relied upon to be satisfied with British indemnities. In return for their help, the British gave them the military support necessary to maintain their little fiefdoms.

Indeed, Britain had no interest in seeing Nigeria or any of its colonies industrialise and therefore compete with domestic industry. Its colonial rule thus deliberately reinforced the most reactionary elements. Far from modernising their colonies, they utterly stifled them.

Britain in Africa today

Britain was simply first among robbers in Africa, the most successful looters of the continents owing to its dominant world position. British rule in Africa was never about ending slavery, or ‘civilising’ people.

British rule brought the most ruthless savagery to the continent, and it did so in order for British capital to obtain fat profits from the starving masses they exploited.

Today, British imperialism is a far more enfeebled force than during the ‘Scramble’ and is by no means the dominant imperialist power on the continent.

Yet British capital in 2022 was the single largest investor in the continent, holding over $47 billion in FDI stock, adding over £2.4 billion in that year alone.

British imperialism still has army bases across the continent, particularly in Kenya and Nigeria, where British capital has the most significant investments. Britain may be entirely incapable of subjugating a third of the continent as it once did, but it is no less predatory today.

Our duty as revolutionaries in Britain is to study and understand the crimes of ‘our’ imperialists, and wage a relentless struggle against it today.

Comrades of the Revolutionary Communist International are fighting to put an end to the capitalist system that led to the colonial subjugation of Africa, and today keeps the continent in a state of underdevelopment and complete dependence.

As the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara stated: “If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine.”

We encourage all those who want to fight against the brutal injustices of our rotten system to get involved in the RCI and help us in this historic task.

The task of fighting for a world in which the people of the world can cooperate to build a socialist society, free from the violence and exploitation inherent in capitalism.