Daniel Morley examines the changing relations between the Philippines and the major imperialist powers, as the country moves from being a firm ally of the USA and turns towards China under the new leadership of Rodrigo Duterte – yet another sign of the growing geo-political instability arising from the decline of US imperialism and the global crisis of capitalism.

Daniel Morley examines the changing relations between the Philippines and the major imperialist powers, as the country moves from being a firm ally of the USA and turns towards China under the new leadership of Rodrigo Duterte – yet another sign of the growing geo-political instability arising from the decline of US imperialism and the global crisis of capitalism.

“I announce my separation from the United States… I have realigned myself in your [China’s] ideological flow… I will be dependent on you for all time.” “I will not go to America any more. We will just be insulted there. So time to say goodbye my friend.” “There are three of us against the world – China, Philippines and Russia. It’s the only way.” (Rodrigo Duterte, new President of the Philippines, on his recent trip to China)

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the United States emerged as the single most powerful nation in the world. This, however, hid its real underlying relative historical decline, which has become more evident in recent years.

The Afghan and Iraq wars served to underline this. Rather than strengthening the position of the United States on the world arena, they merely served to bring out clearly the limits of US power. In the Middle East, it is Russia that has emerged as a strong power. And on a global level we have the growing strength of China. The decline of the US and the rise of a series of local powers explains the growing instability worldwide.

In this context, the latest geopolitical developments in East Asia, in particular the dramatic change of alliances announced by the president of the Philippines, is a harbinger of a far more unsettled and turbulent epoch for world relations.

As Marx explained in The Communist Manifesto in 1848, “The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere.” This was brilliantly confirmed by the rise of imperialism and the spread of capitalist relations throughout the entire globe.

In the quest for new markets and sources of cheap raw materials and lower labour costs, the imperial powers helped foster the development of capitalism in new countries. In this process, however, we saw how historically new powers emerged, such as Japan, Germany and the United States who grew at a faster pace than the old established imperial powers, such as Britain and France. The new balance of power that flowed from this realignment led to a much more unstable world and produced many revolutions and two world wars in the 20th century.

Decades of growth of the rising powers lead to a breakdown in the dominance of the old powers and a painful period of readjustment in world relations and the terms of world trade. What history has taught us about such phases of transition is precisely that they are painful, messy and pregnant with revolution. They take a long time and with capitalism being an unplanned, short-sighted system, such transitions take place chaotically and blindly.

Thus, the rise of China, and the persisting, stubborn power of the US, signals deep, long lasting crisis in all spheres of capitalist society and a long epoch of social revolution.

Chinese trade

China is today the world’s largest manufacturer, but also the world’s largest trader. Since 2009 it has been the largest exporter, and since 2014 the largest overall trader. This is reflected in world ports and shipping facilities, the key infrastructure for world trade. According to 2013 figures, China possesses the first (Shanghai), third (Shenzhen), fourth (Hong Kong), Sixth (Ningbo-Zhoushan) seventh (Qingdao), eighth (Guangzhou) and tenth (Tianjin) busiest container ports in the world.

The United States has none in the top ten – its first entry is Los Angeles at 18! At the present rate of development – if it is maintained, of course – it is estimated that by 2030 China will own one third of the world’s container ships. Already, 30% of the volume of containerised exports in the world are from China, which is three times the quantity from the USA. In 1964, the US had the world’s largest Merchant Marine (the collection of ships needed for trade), it has now been relegated to fourteenth, with China number two.

This powerful position in world trade can and must lead to major shifts in world relations, sooner or later, with smaller weaker nations realigning according to these changes. It is in this context that the Duterte’s dramatic pivot to China has to be understood.

The end of an affair

Rodrigo Duterte is an exceptionally brash politician who makes Donald Trump seem a vision of moderation. His personality looms very large indeed, and as a result it is easy to read his realignment to China as highly capricious and rash. The immediate cause appears to be Obama’s criticism of Duterte’s slaughtering of alleged drug peddlers, to which Duterte responded in his inimitable gangster style by calling Obama a “son of a whore”! Obama then cancelled a meeting with Duterte, which seems to have sealed the rift. The Chinese ambassador smelt blood and moved quickly, releasing the following statement,

“The Chinese side fully understands and firmly supports the Duterte administration’s policy that prioritises the fight against drug crimes… the sun will shine beautifully on the new chapter of bilateral relations.”

From this point onwards Duterte seemed intent on sticking his middle finger up to the United States, and what better way to do that than by cosying up to its great rival, China?

Only a few months ago, US-Philippine relations were the fulcrum of the “contain China” policy. So cosy were they that under US encouragement, the Philippines had taken to the Hague a case against Chinese encroachments in the islands nearby, a case which the Philippines won. In 2016, the Philippines agreed to a massive increase in US military presence in the country (after they were kicked out in 1992), including the installation of an air base clearly aimed at the Chinese.

Now, so suddenly that many of his own generals and security advisers did not know what was happening, Duterte has announced a complete end to all joint military exercises with the US, explicitly stating this was so because “China does not want it”, and the above mentioned agreement to host additional US forces will likely be revoked. Duterte has also demanded the US cease assisting his government in operations against an Islamist insurgency in the country’s south, and the expulsion of all US Special Forces.

By making such an impassioned display of public affection for China, and especially by agreeing to ignore the Hague court’s ruling in favour of his own country, Duterte has actually won for Philippine fishermen precisely what his predecessor, in bringing the case to court, was supposedly fighting for – this week Philippine TV has triumphantly shown fishermen returning from the Scarborough shoal laden with fish. These are the islands China recently grabbed from the Philippines, denying its fishermen the ability to exploit their coasts, but following his love letter to Beijing China has magnanimously agreed to allow Filipino fishermen back into these waters (so long as China can control them militarily!). It is deeply ironic that by embracing China as it annexes Philippine territory, he has actually won back for the Philippines far more than his predecessor could ever have done.

Cold, hard cash

However, flippant and larger than life as Duterte is, can we really explain the realignment of an entire 100 million strong nation on the basis of one man’s fit of anger, or are there stronger, longer lasting interests at work?

The Philippines has learnt the hard way that China carries a lot of economic muscle in the region. Everybody knows how China’s emergence as the world’s biggest trader and consumer of raw materials had a knock on effect in all the other economies tied to it in a wave of growth (which is, admittedly, now coming to an end). Befitting a rising power, it is now becoming one of the biggest exporters of capital too.

But the Philippines’ role as the US’s staunchest ally in Southeast Asia has largely excluded it from Chinese trade and investment, and the Chinese market has been closed for its fruit exporters. China is the only power in a position to help in developing the infrastructure of the Philippines. Chinese investment into the Philippines can be seen as part of the new ‘Silk Road’ and the operations of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (more on these later).

If this was Duterte’s intention, his Chinese pivot paid dividends more rapidly than almost anyone could have expected,

“In total, the two countries signed 13 agreements on Thursday spanning a variety of economic sectors, while Ramon Lopez, Philippine trade secretary, said the two countries had signed $13.5bn in trade and investment deals.

“China’s foreign ministry further announced that restrictions on 27 Philippine fruit growers on exporting to China would be lifted, as would a travel warning to Chinese tourists to avoid trips to the Philippines. China Eastern Airlines, one of the country’s largest carriers, announced the launch of a direct air route from Guangzhou to the Philippine city of Laoag, starting next month…the China Communications Construction Company, a state-owned group, signed a memorandum of understanding with Mega Harbour Port and Development of the Philippines to conduct a 208-hectare land reclamation project in Davao harbour. The reclamation is expected to finish by the end of 2019. No total value was published for the investment” (Financial Times, October 21st, 2016)

Whilst China remains unpopular amongst ordinary Filipinos, it is very popular amongst key sections of the Filipino bourgeoisie, which is what really counts. Many had been unhappy with the former government’s open hostility to China, which they feel affords more profitable opportunities than does the US. Now they are laughing all the way to the bank.

Duterte’s foreign secretary is Perfecto Yasay, a former lawyer who represented Chinese-Filipino businessmen close to Beijing, and who recently stated that “Filipinos will not be America’s little brown brothers.” And as Foreign Policy explained:

“Among Yasay’s prominent clients has been Lucio Tan, one of the country’s richest men, who Duterte has said was one of the first to urge him to seek the presidency. Billionaire Tan was born in China’s Fujian province and is considered on the mainland to be a “patriotic” Chinese. (…)

“Today, he is chairman of Philippine Airlines, the country’s flagship carrier, and has extensive holdings in banking, mining, tobacco, beer, hotels and property development. He’s also made some major investments in China, which have clearly earned him the goodwill of Beijing. When Chinese presidents come to Manila, they always stay in one of Tan’s hotels. (…)

“During his campaign, Duterte received an especially warm welcome from the Federation of Filipino-Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, of which Tan is an honorary chairman. Along with the Chinese ambassador, Tan was one of the first prominent visitors Duterte received after his election victory.

“In his eagerness to establish close economic ties with Beijing, Duterte has also said he is looking to revive various Chinese-Philippine joint ventures that were envisioned a decade ago during the presidency of Gloria Arroyo. The most notable project on Arroyo’s watch involved a $329 million telecommunications contract with China’s state-owned ZTE Corp. But Arroyo’s hopes to forge closer economic ties with China were derailed by various allegations of pay-offs that involved ZTE, Arroyo herself, and members of her entourage. Authorities in Manila recently dropped graft charges against Arroyo and her former colleagues, and her four-year house arrest has been lifted. Duterte has insisted that he had nothing to do with those decisions, though he had publicly offered to pardon Arroyo, in any case.” (Foreign Policy, October 17, 2016)

Evidently beneath the surface of serene and secure relations with the US, significant sections of the Filipino ruling class were itching to re-establish lucrative trade with China. Now the plans that had been gathering dust can be dusted off and Chinese cash can lubricate the wheels of Filipino commerce.

It is of course true that these agreements have yet to be realised and many obstacles remain in place. One also has to take all of Duterte’s inflammatory remarks with a pinch of salt. Yet he has already made good on his grisly promise to execute thousands of drug addicts, and as we have seen his Chinese pivot has powerful interests pushing it behind the scenes.

Perhaps more to the point, Duterte’s highly public remarks have already dealt a blow to US imperialism, whose domination of the all important shipping lanes of East Asia depend to a large extent on prestige and the appearance of being a benevolent protector. The opening of China’s treasure vaults, and importantly with the return of Filipino fishermen to Scarborough Shoal, all have seen that if you strike a bargain with China, you can win more from it than by fighting it. As the Economist says it, “The message for the other South-East Asian nations with competing claims in the South China Sea could not be clearer: accept China’s sovereignty and riches will follow. Najib Razak, Malaysia’s embattled prime minister, turned up in Beijing this week cap in hand.”

If you can’t beat them, build them

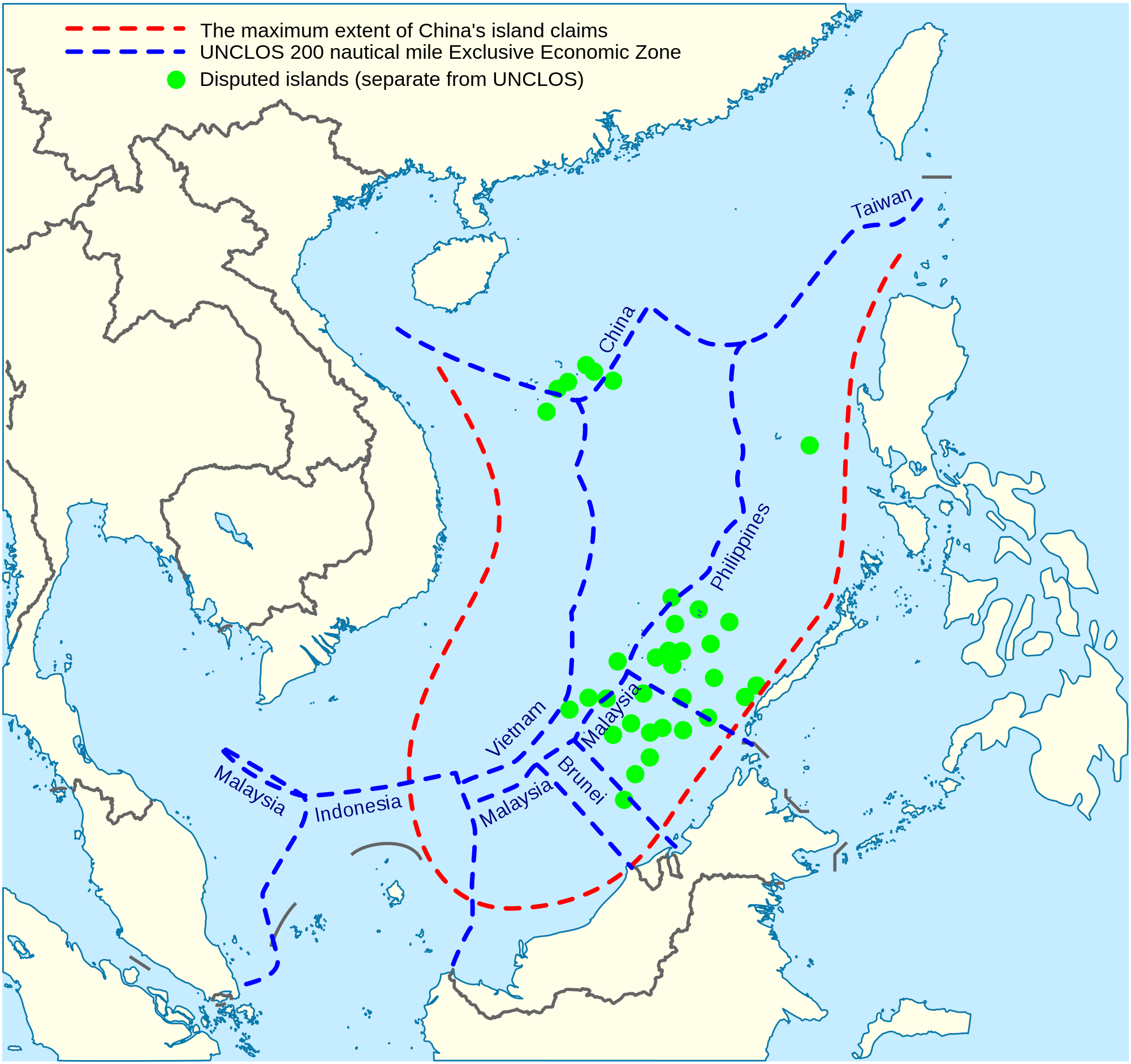

Of course the most dramatic proof of China’s ambitions has been its island building campaign in the South China sea. This is linked to China’s aggressive “9 dash line” claim over this sea and to the seizure of the Philippines’ Scarborough Shoal. There can be no doubt that this expresses China’s objective to wrest control of the South and East China seas from the US, giving China a powerful world position.

Of course the most dramatic proof of China’s ambitions has been its island building campaign in the South China sea. This is linked to China’s aggressive “9 dash line” claim over this sea and to the seizure of the Philippines’ Scarborough Shoal. There can be no doubt that this expresses China’s objective to wrest control of the South and East China seas from the US, giving China a powerful world position.

The “9 dash line” is of course enormously provocative, since, if realised, it would annex to China the seas surrounding all the major nations of Southeast Asia. These countries like China when it trades with them and invests in their economies, and indubitably that is China’s best means to win influence. But China also needs its own military power; to really take control of this region it must have overwhelming military power, otherwise the minnows will attach themselves to the US. This is also why China has recently passed a law allowing its soldiers to be posted in bases in other countries for the first time. It must present to Southeast Asia not just its treasure, but also an overwhelming military force.

It is therefore trying to create, bit by bit, “facts on the ground” (or rather sea). It is banking on America’s ailing power, its overstretched and tired military and its restive working class. It knows that the basis for American power in the region is more military than economic might – the Southeast Asian nations are allied to it for historical and military reasons, for the US Navy is still by far the strongest in the region.

China and all the nations of Southeast Asia are watching the US military. Each time the US fails to intervene, as it did in Ukraine and Syria, it is registered not just in Beijing but in Hanoi, Taipei and Seoul. China does not have to say anything; the combination of US impotence and Chinese aggression speaks volumes. The inability to intervene directly against Russia says loudly and clearly to this region: we cannot intervene to protect you from Chinese incursions; we are too tired, too sceptical, we are overstretched. The conclusion looms: why ally with the US, if the basis for the alliance – naval protection and stability – is no longer real? Indeed, Duterte actually referred to this when visiting Beijing, complaining that the US’s protection is all show. That is why China is provoking by gradually taking more and more sea, or even building new islands. It is testing and proving America’s resolve, or lack thereof.

On the surface, it appears that the US has all these countries in its pocket. And certainly, many of them are still far from becoming China’s. But it is not so simple as that, as the changes in the Philippines and Thailand (more on this shortly) show. For instance, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam all appear to be close US allies. But South Korea trades very closely with China, requires and appreciates its cooperation regarding North Korea, and shares with it a mutual distrust and resentment of Japan which flares up from time to time.

Taiwanese politics is profoundly influenced by fear and hostility toward China, but to an extent this is proof of its grudging awareness of its dependence on China. Economically, Taiwan cannot afford to alienate China, and that explains why its new President, Tsai Ing-wen, elected on a radically anti-China basis, significantly softened her line on China during the election campaign, saying she wanted to preserve the status-quo.

Vietnamese politics is also influenced heavily by anti-Chinese sentiment, but when it came to electing their new president at the Communist Party congress, the pro-West and anti-China candidate had to withdraw for lack of support. The president is known as being “pro-Chinese”, even if the strategic positioning of Vietnam is known as pro-Western. In reality, Vietnam as well as South Korea and Taiwan are now in a position of balancing between the US and China, even if they do lean more to the US side. Over time, the weight of China in this balancing act will surely only grow.

A string of pearls

To gain control of vital shipping lanes, it is working to pull into its sphere of influence strategic islands. One such island, the biggest of them, is already more or less an ally, Sri Lanka. Here China is building key ports that will dwarf any in India, and over which China will have key influence. Already its military submarines dock in Sri Lankan ports, much to Indian dismay.

Sri Lanka for many years has been a de facto Chinese ally. This alliance may be in jeopardy after the election victory of Maithripala Sirisena, who promised to investigate contracts with Chinese companies for corruption. Nevertheless, China remains key for Sri Lanka – it is the only country stopping a UN investigation into war crimes by the state on Tamils, and its biggest investor, with Chinese investment there increasing fifty fold in ten years, more than double that of the US and its allies!

Despite the election result last year, the hard cash and determination of Beijing will probably ensure Sri Lanka becomes an important ally for China:

“Just over a year after a new leader was elected and Sri Lanka’s business ties with China came under close scrutiny, Colombo is reversing course by resuming a stalled port project and naming Beijing as the frontrunner for a new special economic zone. (…)

“Now Maithripala Sirisena’s government, faced with falling foreign reserves, a balance of payments crunch and few, if any, alternative investors, is heading back into Beijing’s embrace, albeit on better terms than before.

“The stance on China has completely changed,” cabinet spokesman Rajitha Senaratne told Reuters.

“Who else is going to bring us money, given tight conditions in the West?” (Reuters, 10.2.16)

China sees Sri Lanka as an important pearl on its so-called “string of pearls” – that is, the plan to establish control of strategic points in the shipping lanes, like the British did with Malta and Gibraltar in the Mediterranean. It is developing an alternative land route to Europe via central Asia; it is also developing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and port at Gwadar to have a route to the sea that bypasses the Straits of Malacca. But this does not mean it has given up on wresting control of the South and East China seas from the US – these are after all its “own back yard”.

Central Asia

China’s strategy extends far beyond the sea lanes and into the underpopulated far reaches of Central Asia with its much trumpeted (and feared) new “Silk Road” or “One Belt, One Road” policy. China’s concern is that it has no military control over the sea lanes it has effectively created. 70-80% of China’s vital oil supply is imported through the Straits of Malacca, but the US navy, together with its “colonies” in Southeast Asia, have strategic control here. In a war or other crisis, China could be deprived of oil and access to its export markets in an instant by the US Navy. It is evidently in its strategic interests to find a way around this.

China’s biggest trading partner outside of Asia is the EU, and most of its oil comes from the Middle East and Central Asia. China has therefore decided that it is in its strategic interests to develop trade routes along the land route to the Middle East and Europe, i.e. to create a new “Silk Road” (confusingly, this is the “one belt” part of the “One Belt, One Road” plan; the “one road” part actually refers to sea routes they plan to develop).

China’s trade with Central Asia had already reached $50bn by 2013, supplanting Russia as the region’s number one trading partner (up an incredible 50 times from $1bn in 2000!). Central Asia has not been an important region of the world, economically or politically, being as it is landlocked and under-populated. And yet it is host to some of the world’s biggest oil and mineral deposits. Not only that, but the region lies slap bang in the middle of the land route between two of the world’s top three economies – China and the EU.

China has already conquered this region economically and is in the process of doing so politically. The Financial Times quotes a leading European economist as saying that “They [China] are increasingly active in all sectors [of Central Asia] and you just cannot see western capital or Russian capital taking their place” (our emphasis). The same article goes on:

“In Kazakhstan, Chinese companies own somewhere between one-fifth and one-quarter of the country’s oil production – about the same proportion as the national oil company. In Turkmenistan [China accounts] for 61% of exports last year… the Tajik deputy finance minister last year told the FT that Beijing would invest $6bn in Tajikistan over the next three years – a figure equivalent to ⅔ of the country’s annual GDP.” The article then quotes Liu Yazhou, a general in the People’s Liberation Army, who called central Asia “a rich piece of cake given to today’s Chinese people by heaven.” (Financial Times, 14.10.15).

Xi Jinping managed to put himself across in a somewhat more tactful, “statesmanlike” and smoother manner when he recently wooed a Kazakh audience with these carefully chosen words, “As I stand here and look back at that episode of history [when China first established the Silk Road], I could almost hear the camel bells echoing in the mountains and see the wisp of smoke rising from the desert… [Kazakhstan is a] magic land”. Having sufficiently tickled the tummy of his prey, he got to the matter at hand: the need to create a new economic belt between China and the world via Kazakhstan.

To successfully create its first sphere of influence, China must realise the economic and strategic potential of this region, but that is a complicated task. The major difficulty presented by Central Asia is that it has always been Russia’s sphere of influence, and Putin is intent on reestablishing Russia’s power. Having China steal away its influence would cut across this.

However, Russia’s rise is limited compared to that of China’s because of its weaker economy. Moreover, Russia has few important allies on the world stage, and is unlikely to gain any. The only significant global power it can ally with is in fact none other than China itself. So ultimately, China will be able to override any Russian protests about playing in its backyard. Indeed, already in May 2015 these two countries signed a cooperation agreement between Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union and China’s “One Belt, One Road”.

Russia looks to be ceding economic leadership in the region in exchange for military leadership. It has become an active member of the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, an Asian “security” association which Putin appears to see as a potential sequel to the Warsaw Pact for the modern world, which he argues is justified by NATO’s violation of the Helsinki Accords. Russia’s arms industry and alliance with China would put it in a perfect position to play the leading military role in this new “Eastern Bloc”.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Standing behind all these ambitions lie the mountains of Chinese cash in its new “Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank” (AIIB).

The AIIB’s first confirmed project is, unsurprisingly, linked very tightly to China’s strategic interests – it is to fund three of the “One Belt, One Road” projects, putting up the cash for key roads in Pakistan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. Through the AIIB and Chinese state owned banks, China plans to spend an initial $46bn investing in Pakistani infrastructure, including not just roads but the key port in Gwadar. This subsection of the new silk road project is called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and China has convinced the Pakistani state to provide the security for this part, with 10,000 of its soldiers guarding the construction from terrorists and the thousands of peasants who will be booted off their land.

Chinese state owned banks are to receive a capital injection from the foreign exchange reserves of $60bn for the Silk Road projects. This new Silk Road plan is the largest act of economic diplomacy the world has seen since the post WWII Marshall Plan (Financial Times, 12.10.15). It extends as far as Nigeria and Zimbabwe, which are to receive $5bn of investment for the railways needed to integrate into this “One Belt, One Road”. And the same phenomenon of Chinese capital exports is found in the private sector as well. Already 2016 has seen over $100bn in cross border mergers and acquisitions by Chinese companies, one third of the global total!

China fears social turmoil and revolution from unemployment brought on by its overcapacity. It therefore sees the investment opportunities surrounding it as a means to keep the factories open and the workers in work: “construction growth is slowing and China doesn’t need to build many new expressways, railways and ports, so they have to find other countries that do… One of the clear objectives is to get more contracts for Chinese construction companies overseas.” (Financial Times, 12.10.15).

The great game

As we have seen, at present the key nations in East Asia are American allies – Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Taiwan. This represents a classic contradiction – the old refusing to die to make way for the new. The booming Chinese economy has made this region the key to world trade, but far-away USA controls the area thanks to its past victories and the fact that although it has been in relative decline, it is still the number one power on a global scale. This contradiction will intensify as time goes on, producing complex and shifting alliances, as we are currently witnessing in the Philippines, power struggles and other kinds of instability. It will also bring out the internal contradictions in these countries as different wings of the national ruling classes lean towards one or other of the major powers, depending on their own specific interests.

Every single one of these countries except Japan has China as its biggest trade partner, not the USA. China will slowly but surely wear down US political and military dominance with the heavy weaponry of trade. The vital importance of maintaining friendly relations with China will bear down upon the politics of each of these countries, just like in the Philippines. It will cause splits in the respective ruling classes as they weigh upon how best to balance between the world’s two superpowers. This process has even been seen as far afield as New Zealand and the UK, traditionally staunch US allies. New Zealand said it would not sign the TPP trade deal if it was designed to contain and isolate China, and the UK fell over itself to sign up to the AIIB, much to the annoyance of the US.

These political pressures in Asia will destabilise the region, spelling the end to this region’s “peace and prosperity”. Indeed there is no shortage of “combustible material” in the region, such as national tensions within and between the nations. In the case of Thailand the tensions are more directly and purely political than national. The events in Thailand are worthy of closer study as they tell us much about how China may attempt to prise away allies from the US in the coming years.

For the past decade Thai politics have been overshadowed by billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra. Shinawatra is, and was, a very close ally or even proxy of the US. Thailand also has for a long time been a key American ally, for example, allowing the use of bases in the Vietnam War. But Shinawatra was overthrown in a coup in 2006. After his sister was elected president in 2011 and carried out his orders, she too was overthrown in a “legalised” coup in 2014. There is no doubt that the forces behind this political turbulence are not Chinese, but the internal politics of Thailand, which are beyond the remit of this article.

But nothing in history is wasted. Major political turbulence in an important neighbour and trading partner could hardly fail to pique China’s interest, especially after it witnessed the US chiding Thailand for undemocratically ousting its own proxy (just as it quickly stepped in to praise Duterte’s drug war after Obama’s criticism). The Wall Street Post writes that,

“Started more than 30 years ago, the annual Cobra Gold joint exercises are among the largest in the world. In 2003 President George W. Bush made Thailand officially a ‘major non-NATO ally,’ a designation that brings the benefits reserved for the most trusted security partners.

“The relationship started to sour after the May 2014 Thai coup, with Cobra Gold downgraded and other U.S. aid and contracts curtailed.”

Pushing Thailand out of its embrace in an attempt to hasten the return of Shinawatra, the US inevitably pushed Thailand further toward China. In contrast to the US’s downgrading of Thai relations, China was the first government in the world to recognize junta chief Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha and is pushing plans for a multibillion-dollar Chinese-built rail network. Since the new military junta was established, its representatives have on several occasions spoken very warmly about China and its government. Last year Thailand controversially deported 109 Uighurs to China. In November 2015, China and Thailand carried out an enormous, two week long joint military exercise for the first time.

But the most telling and significant sign of a “Thai pivot” was the agreement to buy three advanced military submarines from China for $1bn. These submarines would require extensive Chinese training, expertise and ongoing cooperation to be workable, tieing up Thailand into China’s orbit. At present, this order is on hold, no doubt thanks to US pressure. Previously Thailand bought its equipment from US allies like Germany. The deal may indeed not go through, but that Thailand even publicly announced it is of enormous significance. It is more evidence that China can and will attempt to prise US allies away from it, and that internal political instability will play a big role in such transformations.

The reverse has recently been witnessed in Myanmar, which confirms the fact that while the US may be in decline it is still a major force to be reckoned with and will not easily give up its spheres of influence and power. And China, although a rising power, still does not have the strength to simply sweep the US to one side.

In Myanmar, internal political tensions have been fostered by the US for decades. Myanmar’s military junta depended largely on China for support, while the West endlessly promoted its agent Aung San Suu Kyi as a democratic saint. That tactic has eventually paid off, although Aung San has in the process been exposed for what she really is. Myanmar is now moving ever closer to the US, although relations with China remain essential for its investment and growth. It is still by far and away Myanmar’s biggest investor.

Given that it retains such an important stake in Myanmar, whose economy is now expected to grow in importance, China will not give up without a fight. It is highly conceivable that China will pursue a tactic similar to that of Russia in Crimea, South Ossetia, Transnistria and Abkhazia, for along Myanmar’s border with China there are several flashpoints of ethnic tension. There are various ethnic minorities brutally oppressed by the Burmese regime, some of which have taken up arms and wage ongoing guerrilla warfare with the state, such as the Karen and the Kachin. Recently the government inadvertently bombed a Chinese village just over the border with Myanmar whilst trying to attack such rebels.

If Myanmar drifts too far away from Chinese interests, any such mistake could be used by China to destabilise the country. This would be particularly likely with regards to the Kokang paramilitary organisation the “Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army” (MNDAA). The Kokang people in northern Myanmar are ethnically Han Chinese and speak Mandarin. It was in this conflict that Myanmar fighter planes strayed into Chinese territory and bombed a Chinese village, killing five. Tens of thousands of Kokang fled governmental repression into China only last year. Many believe Beijing has funded the MNDAA for precisely this reason – to weaken the Burmese regime and to have an excuse to intervene in the country should it not do what China wants, “to protect Chinese people”. Alternatively, China could lean on the MNDAA to give up its armed struggle, thereby currying favour with the government in Naypyidaw and keeping it in China’s sphere of influence. Either way, the basis for destabilisation in a key flashpoint of the US-China struggle is present.

Today southeast Asia, tomorrow…

China’s influence extends far beyond its own “back yard”. Of note is China’s influence in Ethiopia, a so-called “rising star” of Africa. Ethiopia has essentially enlisted China to build its entire infrastructure, including a new modern metro-rail system for Addis Ababa. Chinese companies are building factories and industrialising the country. Recently China “gifted” Ethiopia the $200m headquarters of the African Union.

China has now upped its foreign aid and input into UN “peacekeeping” forces. It is following all of the steps needed to become a global power. The launch of the AIIB is significant not just for the export of capital, but also its diplomatic triumph on the world stage. The only country that refused to sign up to the AIIB was Japan – and the offer was extended far and wide, including US “poodle” the UK. Indeed, all the European NATO countries signed up. Having perfected its poodle tactic with the US, Britain knew how to deploy it to China. David Cameron quickly forgot about the Dalai Lama and rolled out the red carpet for Xi Jinping in a truly elaborate state visit in 2015. George – ‘I for one welcome our new Chinese overlords’ – Osborne even took the unprecedented step of visiting Xinjiang capital Urumqi as he bidded for British companies to be involved in the Chinese development of its restive Uighur province. He also visited the Shanghai stock exchange, beckoning in the Chinese capitalists to the British market. Britain is open for business!

China’s rise is upsetting the faultlines of world relations. Ultimately America’s strength works to contain the uncontainable, and this equation can only produce explosive results. Over the coming period, China will enter into crisis, which will plunge the world economy into a depression. That will be a watershed moment for capitalism. How capitalism drags itself out of that impasse, if it can, and who leads that effort, will have big implications for world relations.

In spite of China’s growing economic strength, it is still far from repeating what the United States did in successfully superseding Britain as the preeminent world imperial power in the 20th century. There are many differences between the two scenarios. In particular, world capitalism is at an utter impasse, the market is thoroughly glutted and the Chinese economy is therefore destined to stall in the coming period. In fact the world economy stands on the precipice. Chinese overproduction is a global problem, as has become the ever growing pile of Chinese debt. In this crisis-ridden context, the geopolitical instability stalking the world is very unwelcome for all capitalist powers. It cannot afford the kind of wars that would be required for China to supplant the USA, and the workers of the world will not tolerate any moves in that direction. But it is indubitable that Chinese power will challenge and undermine that of the United States like none before it.