“People keep asking me how I feel having left the sinking ship of the Tory Party, and I feel pretty good. We are riding high. The wind is in our sails. I’m on a ship that is actually going somewhere.

“And, of course, as we all know, Reform is a bit of a pirate ship led by a buccaneering, charismatic captain, an ill-disciplined crew – but a powerful ship with a dangerous broadside; a terror to its rivals.

“Now, [our] job…is to help turn this pirate ship into His Majesty’s Royal Navy ship, ready to enter the King’s service and serve our nation.”

These are the words of one of Reform UK’s newest MPs, Danny Kruger, who defected from the Tories last September, adding to the slow trickle of senior Conservative figures who have also jumped ship.

This growing list includes a former Tory Party chairman, an ex-deputy chairman, and most recently (former) Lord Malcolm Offord, who dropped his peerage in order to run as a Reform candidate in next year’s elections for Holyrood, the Scottish devolved parliament.

Kruger’s comments shine a light on a question that the ruling elites in Britain are undoubtedly mulling over: what would a Reform government look like? And can Farage and co. be trusted to take over the reins of British capitalism?

On the latter, until recently, the response from the bulk of Britain’s establishment would have been a resounding ‘no’. And, at least for now, this likely remains the opinion that holds sway in City of London boardrooms and the corridors of power.

But there are signs that Reform is angling to change that, as Kruger’s less-than-subtle words imply.

The ruling class’ unease towards Nigel Farage’s right populist outfit is understandable. For the past one hundred years, the British capitalist class have ruled exclusively through a tried-and-tested two-party system, alternating between the Tories and Labour.

This once familiar arrangement is now in freefall, however. Despite commanding a massive majority in the House of Commons, Starmer’s Labour is caught in a maelstrom of crises. And the Conservatives – the primary political representatives of British capitalism for centuries – are on course for electoral shipwreck.

At the same time, Reform UK is riding high in the polls, buoyed by a wave of dissatisfaction and hatred of the status quo.

📊 NEW | Reform lead by 14pts

‼️ Majority of 120 seats➡️ REF – 32% (-1)

🟢 GRN – 18% (+1)

🔵 CON – 17% (+1)

🔴 LAB – 16% (+1)

🟠 LD – 11% (-)Via @FindoutnowUK, 19 Nov (+/- vs 12 Nov) pic.twitter.com/iP6FFssx42

— Stats for Lefties 🍉🏳️⚧️ (@LeftieStats) November 20, 2025

This impending parliamentary upheaval will have a knock-on effect for every wing of Britain’s state apparatus, which for decades has been staffed by Tory and Labour apparatchiks.

In every respect, then, the political establishment is sailing into uncharted waters.

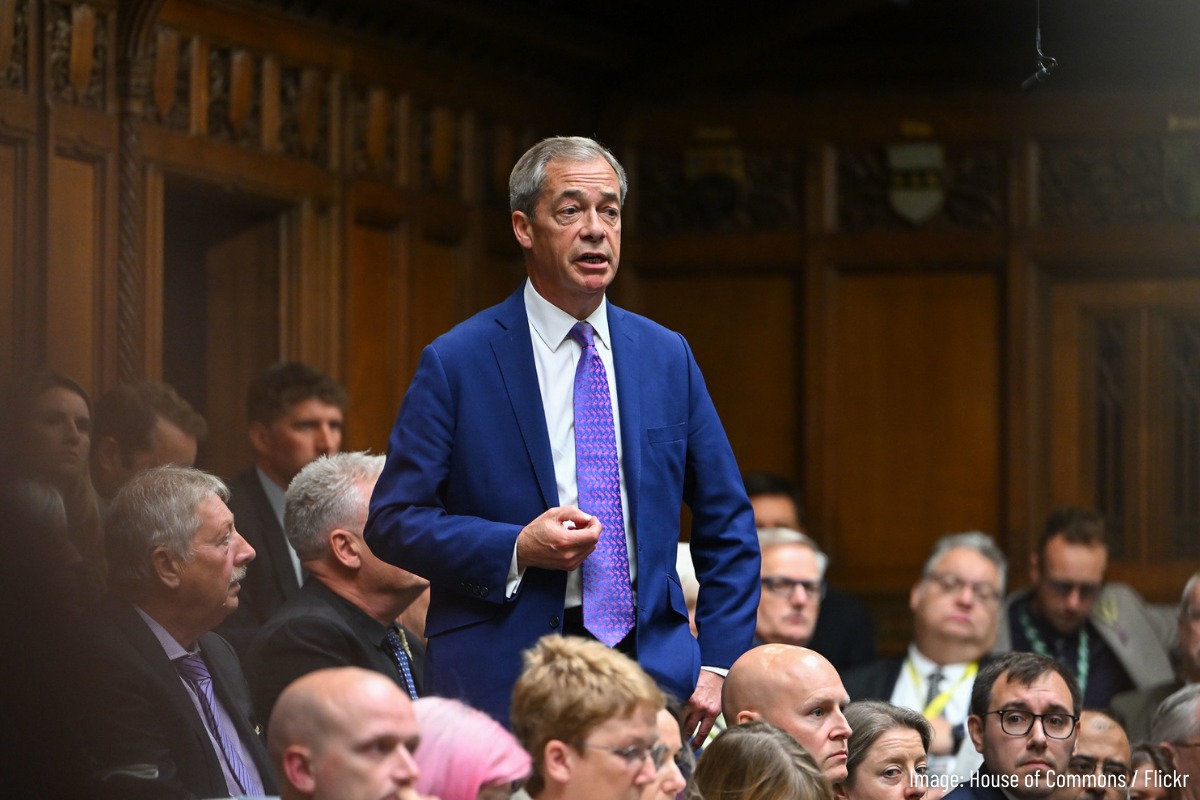

And who is likely to step into the breach? Mr. Nigel Farage.

To the powers-that-be, the Reform frontman and his coterie must appear like a bunch of mavericks and upstarts, recklessly fanning the flames of populist revolt that the establishment is so desperately trying to extinguish.

Compared to the ‘sensible’, sober crew currently at the helm of Britain’s becalmed regime, the unreliable Reform leaders resemble swashbuckling soldiers of fortune. As far as the bosses and bankers are concerned, Farage cannot fully be trusted to take the wheel.

But, with the prospect of a Reform landslide looming on the horizon, the ruling class will be left thinking to themselves: what other choices do we have?

Perhaps these pirates could be turned into state-sanctioned privateers, our rulers might think to themselves, following the good-old traditions of the British Navy.

Reality on the ground

This is the backdrop for recent political developments.

In this year’s local elections in May, Reform won control over ten local councils – a resounding confirmation that they had arrived on the scene as a serious force in British politics.

But despite sweeping into power locally with promises to cut taxes, sweep away inefficiency and waste, and deliver for ordinary working people, the party and its councillors have instead been mired in squabbling, scandal, and controversy.

Several of its councils have been forced to raise council taxes, in many cases above inflation – directly going against what they had promised in their election campaigns.

The party’s plan to set up a Musk-style ‘DOGE unit’ to fight bureaucracy, meanwhile, has hit a brick wall. The best they can offer up is symbolic, culture-war cuts to things like LGBT pride parades and diversity programmes.

Alongside all of this, where they hold the purse strings, Reform has been forced to carry out a bonanza of cuts and attacks on vital local services.

In Warwickshire, the Reform council has taken the axe to school bus services, meaning that children as young as eight may have to walk up to ten miles every day to and from school.

In Lancashire, meanwhile, the Reform-controlled local authority is set to close five council-run care homes, shunting residents into the private sector. The cabinet member in charge of this move, Graham Dalton, just so happens to own a private care company.

These deep cuts to adult social care and children’s services – areas which account for up to three-quarters of local government spending – have left residents, including many Reform voters, feeling betrayed.

“I’m a paid-up member of Reform and I’m disgusted with [Dalton],” one Lancashire resident with an elderly mother told the Guardian. “If there are parents who have paid into the system all their lives, worked hard for this country, if they’re ‘waste’, then we might as well just give up.” He said he would quit Reform if these care homes closed.

This public pressure is bringing itself to bear upon Reform councillors, many of whom probably earnestly believe in the party’s message of fixing the broken finances of local government and delivering for ordinary people.

In Kent, for example, an embarrassing bust-up took place in Reform’s ‘flagship’ council. A leaked video showed the council’s leader telling her cabinet to “f**king suck it up”, in response to their opposition to the local authority’s austerity budget.

Despite hiking taxes and cutting services to the bone, Kent council is still set to overspend by over £46 million.

This confrontation led to several Kent councillors being expelled from the party, with Farage’s backing.

And this is no isolated case. In fact, a whopping 1-in-18 Reform councillors have either been expelled, suspended, or have resigned in the past seven months since the May elections.

This all provides a glimpse of the crises and contradictions that would confront a national Reform government.

Faced with the dire state of the UK’s public finances, such a government would have no choice but to take on the baton of austerity from Starmer’s Labour and the Tories, and continue hacking away at what remains of the postwar welfare state – a ‘luxury’ that British capitalism can no longer afford to provide.

‘Nationalisation Nigel’

Steering the party’s course through these troubled waters is the demagogue-in-chief, Nigel Farage.

Until recently, the Reform leader’s focus was on appealing to working-class voters in ‘left-behind’ areas of the country, including former Labour heartlands.

To this end, Farage has made a whole host of opportunistic economic pledges. This has included promises to nationalise British Steel and Thames Water, scrap the hated two-child benefit cap, and reverse Starmer’s cuts to winter fuel payments.

The public has been entreated to the disorienting spectacle of Farage holding up trade union placards in a steel mill photo-op, and refusing to criticise the Birmingham bin strikers. Similarly, Reform MP Richard Tice donned a trade union badge in the House of Commons.

In many respects, Farage has been tacking to the left of Labour on key economic issues. This was part of a conscious strategy to “park Reform’s tanks on Labour’s lawn”.

The establishment media proclaimed this a “handbrake turn to the left” on the part of Reform. The Tories dubbed Farage “Corbyn with a pint and a cigarette”.

In one interview, Farage himself even went as far as to note the “crossover” between himself and Jeremy Corbyn:

“[We’re both] anti-establishment, obviously, [and share] a sense that the giant corporations now dominate the world that we live in, that politics is very much in the pocket of the big corporates.”

“We’re both anti-establishment.”

Nigel Farage says his and Jeremy Corbyn’s political ideology has a lot of crossover. pic.twitter.com/iciOHddT1A

— PoliticsJOE (@PoliticsJOE_UK) January 7, 2025

Establishment overtures

As of late, however, all this heady talk of nationalisation and corporations dominating the world has been sidelined in favour of more establishment-friendly language.

In a City of London speech last month, for example, clearly aimed at Britain’s business leaders, Farage toned down his pledge to nationalise British Steel. Similarly, he walked back on his promise to completely scrap the two-child benefit cap.

Even the costly ‘triple lock’ on state pensions – the ‘sacred cow’ that British politicians dare not touch, lest they enrage millions of elderly voters – has recently been questioned by the Reform leadership.

This is a risky move, given that around 30 percent of Reform’s supporters are of pension-age, and over half are older than 55.

Instead, the Reform leaders have promised a Thatcherite programme of deregulation, complete with a ‘Big Bang’ in the financial services sector, with the aim of becoming “the most pro-business, pro-entrepreneurship government this country has seen in modern times…free[ing] businesses to get on and make more money.”

Interestingly, even some of the more libertarian edges of Reform’s programme have been sanded down. For example, Farage has ditched his £90 billion tax cut pledge, and is now emphasising the need for fiscal responsibility and “realism about the state of the economy”.

If this all sounds a bit like what Starmer and Reeves were saying in the run-up to the 2024 election, then you’re not wrong.

It appears that Farage, just like his Labour predecessors, is trying to lower voters’ expectations in advance of coming to power; preparing workers for the ‘tough decisions’ that he and his party will be forced to carry out down the line.

Elsewhere, on foreign policy, Farage has also toned down some of his rhetoric, in order to bring Reform more in line with the views and aims of Britain’s imperialist establishment.

Previously, the Reform leader echoed US President Donald Trump in his scepticism towards the West’s involvement in the Ukraine war – even (correctly) going as far as to say that NATO provoked the war in the first place. This provoked the ire of all the liberal media outlets and pro-Ukraine headbangers in the establishment.

In recent months, however, Farage’s approach has shifted. Now he is defending Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky; pledging to send a British peacekeeping force to Ukraine should he enter Downing Street; commenting that Britain should shoot down Russian jets if they enter NATO airspace; and criticising Putin as “an incredibly dangerous man” whose demands for Ukrainian territory are “not acceptable”.

In yet another clear overture towards the capitalist establishment, Farage is rumoured to have recently told party donors that he expects Reform will do an electoral deal – or even merge – with the Tories ahead of the next general election!

In public, however, the Reform leader says that his aim is still to replace the Tories, not enter into an alliance with them. How does one make sense of this apparent contradiction?

On the one hand, Farage is astute enough to know that the bulk of his supporters back Reform precisely because they despise the Tories (and Starmer’s Labour). Hence the need to maintain a clear distance between his party and that of Kemi Badenoch.

At the same time, Farage is effectively telling his party’s wealthy backers (and potential backers) that Reform is willing to act in the same way as the Tory Party that they know and love; that a Reform government would be ‘business as usual’ for the capitalists. This is the conclusion that certain bourgeois commentators are also drawing.

On all accounts – on the economy, foreign policy, and electoral strategy – Farage is sending a clear message to the ruling class: ‘You can trust us. We will do as you say’.

This ‘charm offensive’ already seems to be having an impact. Earlier this month, for example, Reform received a £9 million donation from businessman and ex-Tory donor Christopher Harborne – the biggest single donation to a UK political party by a living donor.

Similarly, the wife of Lord Rothermere, Claudia Harmsworth, recently made a £50,000 donation to Reform. Lord Rothermere owns the traditionally Tory-aligned Daily Mail, alongside other newspapers like Metro and i, and is currently eyeing up a bid for the Telegraph too.

This steady trickle of big-business backing has now placed Reform ahead of the Tories, Labour, and the Lib Dems combined in terms of fundraising from donations in the third quarter of 2025. Farage’s outfit are also on track to beat the two main parties for total donations raised this year, which is possibly unprecedented.

This is far from a floodtide of support. But it provides an indication of where things are heading.

All things to all people

Of course, impressionistic journalists have once again been taken in by the latest zig-zag in Farage’s strategy. The same liberal outlets that hailed Farage’s “turn to the left” are now announcing – with equal credulity – his “return to Thatcherism”.

It would be a mistake, however, to get swept up in each and every twist and turn by Reform, or to hang on every word that falls from the lips of demagogues like Farage.

Such empiricism is the stock-in-trade of liberals and reformists. Genuine communists and class-fighters, by contrast, must avoid being dazzled by the shimmering surface of events, and understand the underlying processes at play.

The essence of populist demagogy is to promise ‘all things to all people’. An opportunist creature like Farage is more than happy to pounce on events and tap into ephemeral moods in society, provided this serves his personal, narrow interests.

To this end, he will gladly promise nationalisation to workers one month, while assuring the capitalists that he will safeguard their profits and privileges the next.

This reflects the contradictory and heterogenous social forces that lie behind populist outfits like Reform and the MAGA movement: an unstable coalition compromising working-class supporters with a hatred towards the establishment, sections of the enraged middle-class, and certain layers of the bosses and bankers.

Reform’s latest manoeuvres are therefore not some decisive ‘shift to the right’, nor a fundamental transformation in its social and political character, as some might argue. Rather, Farage’s inconsistent, erratic, ‘vibes-based’ approach to politics is entirely in line with populism as a broader political phenomenon.

Instability ahead

In many cases, the closer that populist politicians get to power, the more they moderate themselves – bringing them more in line with the interests of the liberal establishment and the big bourgeoisie.

Italy’s Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, is the clearest example of this, with her willing adoption of an austerity agenda and pro-NATO programme from day one. Marine Le Pen in France is also heading this direction, purging the more overtly far-right layers of her party, and explicitly coming out against striking workers.

This same process lies behind what Farage is doing now. Should he get the keys to Number 10, the weak position of British capitalism would leave him no wiggle-room to placate his social base and challenge the establishment.

Farage is making overtures towards the ruling class, while dampening the expectations of his downtrodden social base. This doesn’t, of course, bar him from making further ‘left-wing’ promises and gestures to his working-class supporters down the line, where necessary.

All the while, unable to meet the contradictory demands of those looking towards Reform, Farage and his party will be forced to rely even more on whipping up racism and leaning on culture-war rhetoric.

It’s clear that the establishment doesn’t completely trust Reform just yet, even if individual business leaders are beginning to sense which way the wind is blowing, and are pragmatically engaging with them.

Next May, elections will take place in the Scottish and Welsh devolved assemblies, as well as in a number of local authorities across the country.

Reform is projected to make considerable headway in these elections. And any seats that they win will provide them with more opportunities to assure the establishment that they will be a ‘safe pair of hands’ for British capitalism.

As for Farage himself, he can no doubt see some of the dangers that lie ahead: the trials of attempting to govern over crisis-ridden British capitalism; the need, if propelled into power, to walk along the well-trodden path of austerity pursued by all previous governments.

This will unleash enormous instability, as all the anti-establishment rage in British society – hitherto partially captured and misdirected by Farage’s gang – crashes up against the rocks. Where will this anger be directed next? Which fresh outlet will it find?

We do not have a crystal ball in order to answer these questions precisely. And there is no point in speculating about events years into the future, at a time when it is still Starmer and his cretinous clique that are wielding the knife and attacking the working class.

We can say for certain, however, that a Farage government – and any administration that keeps within the confines of capitalism – would solve absolutely nothing.

Rather, such a development would intensify the crisis of British capitalism, further radicalise consciousness, and thereby accelerate the forces driving Britain towards social revolution.