“Divide et impera was an old Roman motto, and it shall be ours.”

– Lord Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay, minutes presented to the Peel Commission (14th May 1859)

From end to end of the Empire, which covered around one sixth of the Earth’s landmass, the British ruling class enacted ‘divide and conquer’ policies that created deep, violent sectarianism. These policies still cast a dark shadow over these nations today.

The expansive list of British horrors are too great to cover fully. This article will focus on British imperialism’s divide and conquer in India, Ireland, Sri Lanka, and Nigeria.

Brutal sectarianism was fostered in all these places, following broadly the same trajectory: giving economic, military, and political power to one ethnic or religious group, in exchange for loyalty to the British, and in order to pit those exploited and oppressed by imperialism against each other.

Unsurprisingly, this game played in the offices of Whitehall came with enormous human costs in the colonies. It is fair to say that millions have been killed because of these divisions created by the British imperialists.

Conscious policy

From its inception, the British Empire attempted to build groups of loyalists in colonised countries. Before the mid-1800s, this looked different across the Empire.

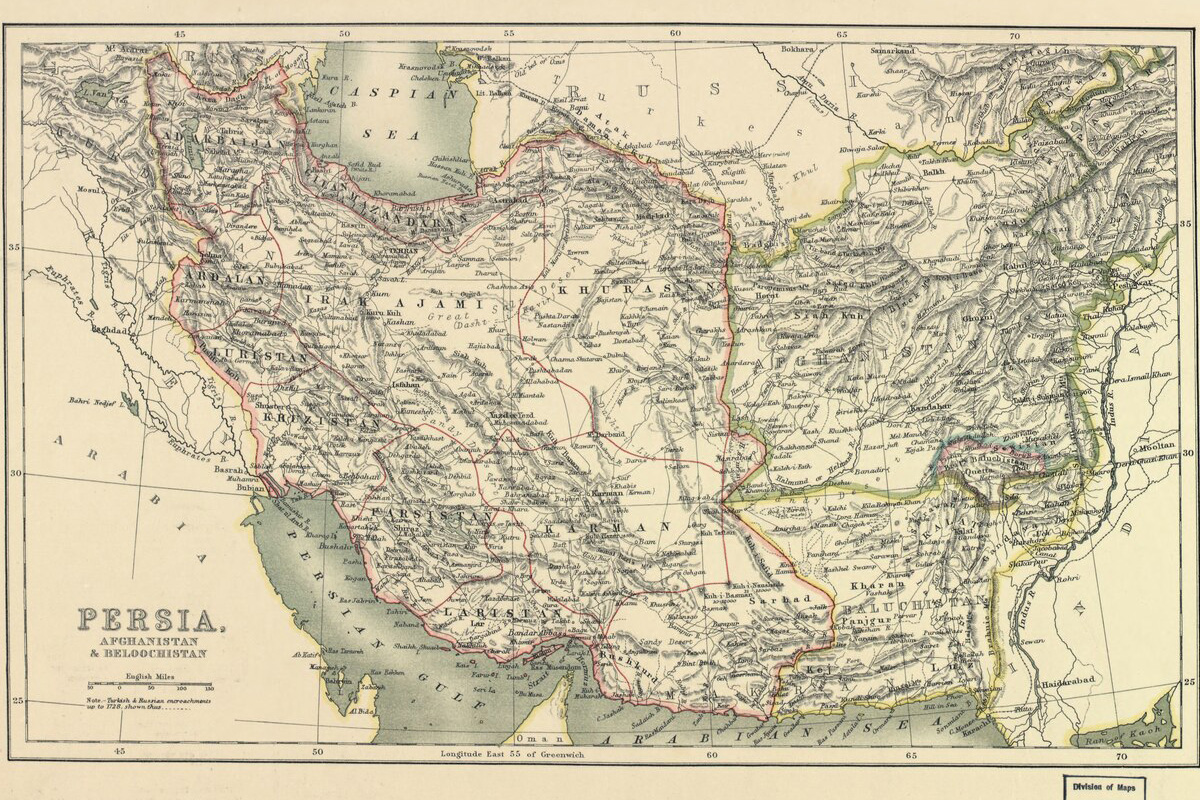

The turning point, when Britain became conscious of the value of ‘divide and conquer’, was brought about by the Indian war of independence in 1857.

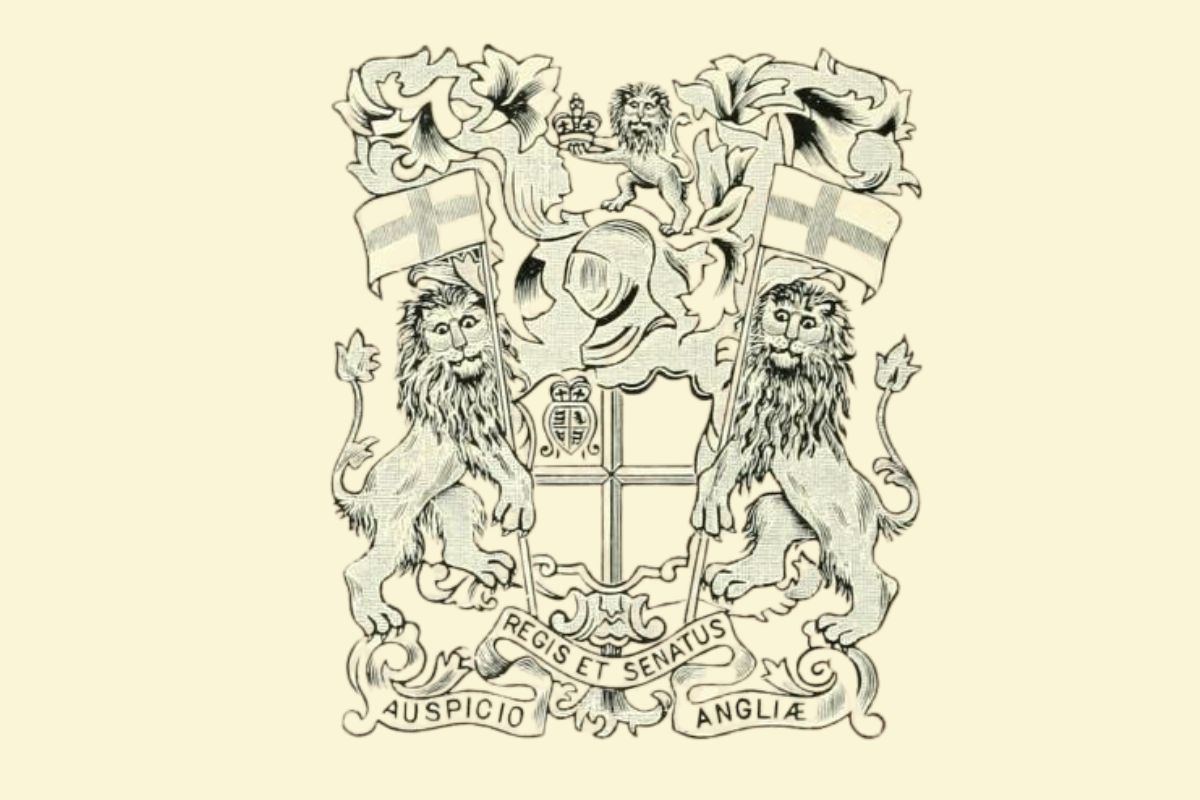

The uprising – beginning in the Bengal army, sweeping across India, and including all religious and ethnic groups – pushed the East India Company back so vehemently that they could no longer effectively rule India.

Luckily for British capitalism, the state came to the rescue, establishing crown rule over India in 1858. However, the British state was now deeply mindful of the fact that important colonies could be ripped out of their grip by revolution.

Discussion dominated Parliament on how to keep these colonies. In one of these debates, Lord Wood said:

“We have maintained our power in India by playing off one part against the other, and we must continue to do so. Do all you can, therefore to prevent all having a common feeling.”

Military reorganisation

Since the mutiny had begun in the army, the first strategy of the British imperialists was to divide the army.

Since the mutiny had begun in the army, the first strategy of the British imperialists was to divide the army.

Native Indians were needed in the army, since British soldiers could not be created in the numbers needed to colonise a continent-sized country like India. Moreover, British soldiers cost eight times as much as Indian soldiers, and could not fight in India as effectively because of the heat.

As proven by the mutiny, this posed a risk to the imperialists. Giving weaponry and training to those who have every reason to hate you is not a smart move. In the offices of Whitehall, state officials discussed how to cut across the developing feeling of anger in the Indian Army.

Lots of disagreement existed over this question. Ironically, however, all those involved were united over one thing: the need to create religious divisions.

From this point on, the British state crafted a careful hierarchy of races in India, which they divided into ‘martial races’ and ‘non-martial races’.

From now, the British filled the army with ‘martial races’, who they considered stupid and loyal to authority. Once in the army, all was not equal. A soldier’s role, and pay grade, was determined by their race and religion.

Religious separatism

Over time, these religious divides seeped out from the army and into Indian culture.

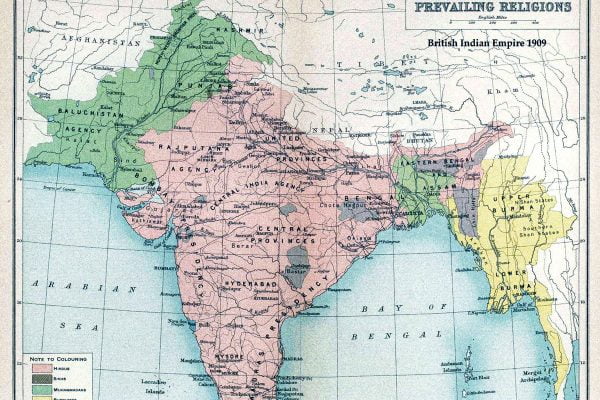

The British furthered this. For example, the census that the British enforced on India divided the population into Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh.

Prior to this, these broad categories were rarely used in India. Religion had been broken down into many different small sects, as well as lots of ‘fluid’ religions, which brought in elements of Hinduism and Islam.

Now, the British had created fixed, defined, and culturally-significant religious groups that impacted social status. Sectarian political groups emerged.

The key mastermind of this was Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, a man entirely loyal to both the East India Company and the British Raj. In 1888 he said:

“In whose hands shall the administration and the Empire of India rest? Now, suppose that all English, and the whole English army, were to leave India, taking with them all their cannon and their splendid weapons and everything, then who would be rulers of India?

“Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations – the Mahomedans and the Hindus – could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not. It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other and thrust it down. To hope that both could remain equal is to desire the impossible and the inconceivable.”

Clearly, these ideas promoted the view that without the British, Muslims would find themselves beaten down and oppressed by Hindus.

Muslim League

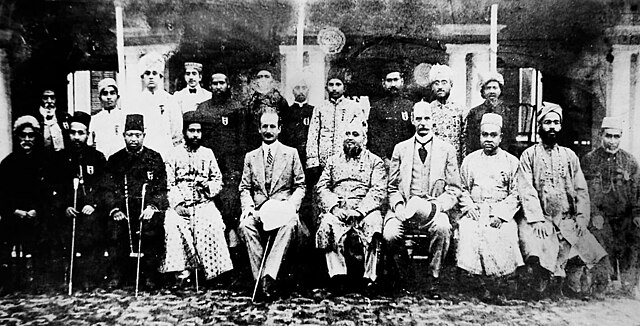

Through this, the ‘All India Muslim League’ was created. Founded in 1906, this group claimed to represent all Muslims in India against the ‘Hindu majority’. This group would become an important tool in the hands of the British Empire.

In 1908, with a push from the Muslim League, separate electorates were created for Muslims in India. This provided Muslims with reserved seats in all councils, creating the message that in order for Muslims to live safely and happily in India, they needed Muslim representatives.

In the early 1930s, after a decade of pro-independence protests, the British used these religious divides to maintain their rule with a veneer of representation.

The British held ‘round-table talks’ to discuss the future of India with representatives of different groups. Because of the sectarianism the British had created, none of the groups could agree, leaving the British as the ‘unbiased mediator,’ able to maintain their position.

Once the talks concluded, this idea was broadened out to the entirety of India, where separate electorates via religion were created. Through these tactics, the British created a politics dominated by religious titles.

Up until 1937, the Muslim League was a relatively unimportant political group, which could only make an impact in Muslim areas of India.

After their failure in the 1937 election, winning only half of the seats reserved for Muslims, they fought to establish relations with the British to help bolster them. The British gladly obliged, in exchange for the Muslim League’s support in WWII.

Originally, the League had three demands:

Originally, the League had three demands:

-

- No decision regarding the future of India should be made without approval of the League.

- The British should “take into its confidence” the League, which should be seen as the only representative of Muslim India.

- The British should satisfy the demands of the Arab Nation in Palestine.

The British agreed to the first two demands, and the League quickly dropped the third.

The reactionary, separatist ideas of the League were pushed into mainstream politics by the British Empire. The conclusion of this is well known.

Deep and violent sectarianism developed in India. And by the time India was partitioned, unspeakable horrors had been committed.

Home Rule in Ireland

The British did not limit the newly-perfected ‘divide and conquer’ strategy to India. In Ireland, a sectarianism was created by British imperialism that persists to today.

Nearly 30 years after the Good Friday Agreement established a so-called ‘peace’, ‘peace-walls’ – built metres high to stop bombs being thrown over – still stand.

In the North of Ireland, at the time the most profitable part of the country, divide and conquer was a simple step, given the previous policy of the British.

In the 17th century, there had been a mass expulsion of native Irishmen from the North. They were replaced by Scottish and English farmers, who the British state thought would provide them with a base of support.

In the latter part of the 1800s, after the great famine (a British made disaster that starved the Irish), Catholics were deliberately oppressed in Ireland to create a sectarian mentality.

In the North, Protestants were trained in the skilled, better-paying jobs. By 1911, less than 10 percent of the workers in shipbuilding were Catholic, while around 11 percent in engineering were. This was despite one third of Belfast’s population being Catholic.

Throughout this period, a Tory-Orange alliance was created, with Conservative governments relying on the Orange Order to suppress not only anti-imperialist struggles in Ireland, but also workers’ struggles.

Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald said of the relationship:

“In Belfast you get labour conditions the likes of which you get in no other town; no other city of equal commercial prosperity: from John O’Groats to Land’s End, or from the Atlantic to the North Sea. It is maintained by an exceedingly simple device… Whenever there is an attempt to root out sweating in Belfast, the Orange big drum is beaten…”

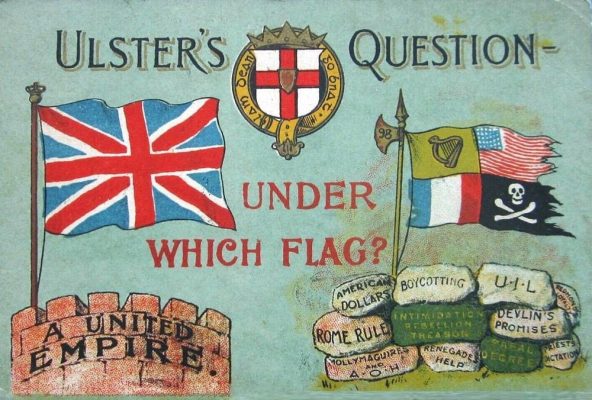

After the failure of the first proposed legislation to grant ‘Home Rule’ to the Irish, the Orange Order began an anti-Catholic pogrom. These would continue throughout the late 19th and 20th century. Home Rule was becoming more and more popular in Ireland, and the British could feel the ground collapsing under their feet.

In a desperate attempt to keep a hold of Ireland, divide and conquer was furthered. When Home Rule was discussed in 1912, Lord Carson was given support by the Conservative government to organise a Unionist militia to protest it.

Money and resources were also put into the creation of the Ulster Volunteer Force – a reactionary mob, which Lenin likened to the Black Hundreds in Russia. They were armed with 25,000 rifles from the British.

Irish partition

In 1921, Home Rule was achieved. But this came at a cost: partition. The British ruling class cast off the majority of Ireland, which was unprofitable and troublesome for them, and kept the industrialised, protestant-majority North, where all the money was made.

In 1921, Home Rule was achieved. But this came at a cost: partition. The British ruling class cast off the majority of Ireland, which was unprofitable and troublesome for them, and kept the industrialised, protestant-majority North, where all the money was made.

Divide and conquer policies did not end here. The Northern Irish state was carefully crafted to include a Protestant majority of two-thirds. 16 British army battalions were stationed in the North, and the Royal Ulster Constabulary was created to police the new state.

Sir James Craig, the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, claimed: “All I boast is that we have a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people.”

The Northern Ireland Special Powers Act was also passed, which banned protests and assemblies, and gave the right to refuse inquests into deaths at the hands of the police.

By the 1960s, decades of deep economic, social, and political repression had taken their toll on Catholics. Segregated areas had come into existence, with the Catholics relegated to slums. Businesses would exclusively hire Protestants, and political gerrymandering took place to quell the voice of Catholics.

When the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, this further codified sectarianism inside the borders of Northern Ireland, in the name of representation.

The history of the North of Ireland has been one of untold sectarian violence. The bloodshed in this region must be firmly placed at the feet of the British state.

Unification of Nigeria

It was not only partition that British imperialism used. Unification was also a tool in their belt.

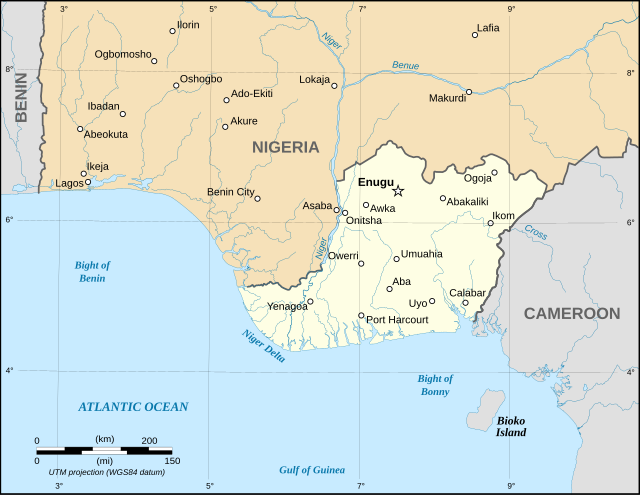

In Nigeria, the formation of one state came alongside massive suppression of the Igbo people, leading to the horrors of the Biafran War in the late 1960s.

In 1914, the country was forcibly united. The resultant population included four major tribal groups: the Hausas and Fulanis in the North; Yorubas in the West; and Igbos in the East.

Before British involvement, inter-tribal violence had been minimal.

In the run up to 1914, the British had developed their strongest relationship with the Hausa-Fulanis, who already had certain levels of governmental organisation. This made it easier for the imperialists to rely on the old rulers, who could be bought off.

When the Nigerian state was created, the British leant on this relationship with the Hausa-Fulanis. Nigeria’s finances were controlled by the British, who funnelled money from the Yoruba and Igbo regions to the North, enriching the area.

Military might was also given to the Hausa people, with a mentality that Igbo people, who had previously been the most problematic for the British, must be watched over.

Yorubas, who were in the area with the most capitalist development, were given education, especially in the English language. This provided higher paying jobs.

The sectarianism crafted by the British cut so deep that it endured long after Nigeria gained independence in 1960. Anti-Igbo pogroms at one point were leading to the deaths of 30,000 per month.

In 1967, a nation of the Igbo people, Biafra, seceded from Nigeria. However, it was very quickly surrounded by Nigerian forces, and starved out of existence. In only two-and-a-half years, somewhere between 500,000 and 2 million people in Biafra were starved to death.

This is the legacy of British imperialism.

Tamil and Sinhalese sectarianism

Another ex-British colony that saw sectarian war after independence is Sri Lanka.

What was then known as British Ceylon is made up of two main ethnic groups: Tamils and Sinhalese. The Sinhalese make up around 75 percent of the population, whereas the Tamils make up around 11 percent.

Despite this, native Tamils were given certain privileges, with the British resting on this demographic as loyalists.

Tamils were given better access to housing and infrastructure. As well as this, they were educated in English, with a westernised education that allowed them to get better paid jobs in the civil service, universities, hospitals, and legal firms.

Once independence had been gained from the British, the Sinhalese ruling class used sectarianism to further their own ends. Sinhala was branded the only official language of Sri Lanka. This cut Tamils off from the jobs they had previously been used to.

Pogroms against Tamils took place throughout the second half of the century. Two brutal civil wars have dominated Sri Lankan life, because of this sectarianism.

Once again, the British left festering wounds that have held back another ex-colony, leading to untold suffering.

Class struggle and unity

Everywhere that British imperialism created this sectarianism, the impact can still be seen and felt today.

Everywhere that British imperialism created this sectarianism, the impact can still be seen and felt today.

There have been brief respites where class consciousness has cut across these reactionary divides, however.

Class struggle has shown that it can lay the basis for an end to divisive sectarianism, racism, and sexism, and forge a genuine unity amongst the working people.

This is because the real interests of working-class people are the same, whatever their ethnic or religious background. In struggles such as strikes, it becomes clear to workers that the more united they are, the stronger they are.

One example of this is the mighty dockers’ strike in 1907 in Belfast. Jim Larkin, a revolutionary trade union leader, led over 3,000 dock workers to demand better working conditions. Both Protestant and Catholic workers united in this struggle.

Many local strike leaders were Protestant – an unusual situation for the time. On 12 July, a day usually consigned to large Orange Order demonstrations and violent oppression of Catholics, strike leaders gave speeches against sectarianism. 10,000 workers marched in support of the strike, with music from Protestant and Catholic traditions.

Similarly, the growth of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) in Sri Lanka after WWII proves the same point.

A brief respite from the Tamil-Sinhala sectarianism was found in the growth of this mass Trotskyist party. It had a large base amongst Tamil plantation workers, despite being led by Sinhalese intellectuals.

It was able to cross the sectarian divide because it fought for the interests of all workers, and was therefore never seen as sectarian.

It was able to cross the sectarian divide because it fought for the interests of all workers, and was therefore never seen as sectarian.

Again, in 2022, when the Sri Lankan revolution kicked off, the Sinhala majority looked to involve the oppressed Tamils. Revolution spread across the ethnic divides, with Tamils and Sinhalas standing side by side in action.

Through these events, it is clear to see that there is nothing inherent about these divides.

Sectarianism is a product of colonial rule, which aimed to distract the local population from seeing who their true enemy was.

Through genuine class-struggle methods, however deep rooted it seems, sectarianism can begin to wash away.

The class struggle teaches the exploited and oppressed masses the truth: their real enemy is the ruling class, and not ordinary people from different religious or ethnic backgrounds.

End sectarianism! End capitalism!

Whole continents have been ravaged by the imperialists through destructive division, in the interests of the ruling class.

Divide and conquer may have been a tactical policy choice by the British. But lying beneath it is the cold logic of capitalism and imperialism.

Imperialism – whether slavery in West Africa, the looting of India, and the cheap labour gained from all corners of the Empire – made the British ruling class untold wealth.

As the owner of the East India Company, Robert Clive became the richest man in the world. The slave trade brought in what would number hundreds of billions in todays money.

For this reason, the British state had an interest in keeping hold of these colonies. Divide and conquer was their method.

Despite this, it is clear that sectarianism and racism – British imperialism’s criminal legacy to the world – can be overcome.

In order to do away with these poisonous ideas, we must finally rid ourselves of the class that benefits from them, and show that working-class unity is the only way to end the horrors of capitalism and imperialism.

Down with sectarianism! Down with capitalism!